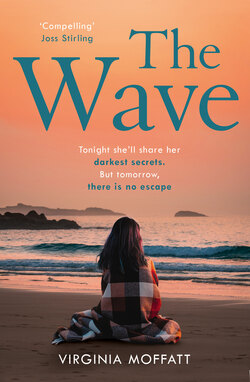

Читать книгу The Wave - Virginia Moffatt - Страница 10

Poppy

ОглавлениеI stand at the top car park, gazing down on the beach below. If I needed any confirmation the news is not a hoax, the silence and emptiness provide it. On a sunny August Bank Holiday, with an offshore wind, the sea should be full of surfers and screaming children diving through the waves. The sand should be crammed with family groups, couples sunning their bodies side by side, pensioners in their fold-up chairs. Everywhere should be movement: parents struggling down the slope with bags and beach balls, their offspring running ahead, shouting in anticipation of the joys to come, people in wetsuits striding towards the water, surfboards under their arms. But the beach is vacant, the air free of all human noise, the only sound the screeching gulls and the ruffle of the wind in the bushes behind. It is as if the world has ended already and left me, a sole survivor, to survey the remains. Normally, the sight of an empty shoreline would fill me with joy – the knowledge that these waves are for me alone – but not today. Today, I find myself unable to move, either to the car to collect my belongings, or to the beach below. Instead, I stand by the sea wall, staring at the yellow sunlight glistening on the blue-green waves, listening to the birds whose calls rise and fall with my every breath …

Years ago, when I was little, I used to stand at this spot, on the last day of the holidays, not daring to go down. Every step forwards was an admission that it was nearly all over, that there was nothing to look forward to but the long journey home and school the week after next. Every year, Mum, perhaps, sensing my emotions, and who knows, maybe even sharing them, would tap me on the shoulder, ‘Come on, I’ll race you,’ she’d say, knowing that my desire to win overtook every other feeling. Standing here, I’m overwhelmed by a wave of longing for her, wishing she was here, issuing me with such a challenge again. A useless desire at the best of times – she has been gone so long, I sometimes struggle to remember her face and voice – but today it seems more pointless than ever. What could she do, if she were here? What can anyone do?

A glance at my watch is a reminder how quickly the minutes are passing. The sun is still high in the sky, but it is moving inexorably towards the west; the surf is at its best now, but that will pass. I need to get down there if I am going to make the most of it. And really I should make the most of, and stick to my plan, otherwise I might as well have gone with the others in the van. I have to be decisive. I return to the car, grab my rucksack, tent and surfboard and walk towards the slope. I will have to come back later for the furniture and refreshments, but it’s still awkward carrying so much stuff. I stagger down the stone path, which gradually gives way to sand, first a light dusting and then my feet are sinking among the hot grains. It is a struggle to stay upright with all the equipment I am carrying, but I force myself forward, sliding down the incline until I reach the firmer sand just above the high tide mark where it is a relief to put everything down. As I am sorting out the pop-up tent, a memory surfaces – another day, another pop-up tent, another beach – Seren and I preparing for our first surfing adventure. ‘It’s not as good as Dowetha,’ I’d said, ‘but it will do.’ I had had every intention of bringing her to Dowetha one day, before everything went wrong between us. I never will now.

Once I have set up camp, I realize I am happy to be alone for once. I appreciate the freedom of undressing with no one watching, the fact that there is no one in my way as I run to the shore. No one to jockey with for the best position in the water. No one to block me as I throw myself into the ocean, drenching myself in the spray and foam. The sea has been waiting for me; I gasp at the cold, as it welcomes me into the rise and fall of its chilly waters.

When I have acclimatized to the shock, I paddle out to the breaker zone, watching for the swell coming from the horizon. I position my board, wait for the right moment, and then stand upright to ride the wave. Soon I am lost in the act of riding through water and foam, warmed by the sun, cooled by the wind, repeated over and over again. I am so absorbed that, at first, I don’t notice the man on the surfboard. It is only when he has paddled to the breaker zone a few yards away from me that I spot him. He is tall, white, with a mass of curly hair. He nods hello and I acknowledge him with a raised arm. I don’t like to talk when I’m surfing. I prefer the silent communication of lying in wait together, rising to hit the crest at the perfect moment, sweeping towards the beach at speed until the foam peters out into tiny bubbles, where we can jump off and head back to our starting point. Over and over again, we follow the waves in the same pattern. Occasionally, I give my companion a smile after a particular good ride, but in the main we are both focussed on the line between the area where the surf forms and the beach. Our world is reduced to this one short journey from sea to shore, over and over again until I have lost count of how many waves we’ve ridden, how long we’ve been in the water.

At last, the chill of the sea begins to penetrate my wetsuit, my shoulders start to ache, and so I shout, ‘Last one?’ He nods, and we ready ourselves for the next swell. This time, as we mount our boards, the wind builds up and it is harder to stay steady. I crouch down low to avoid toppling off, glancing behind to see a mountainous wave racing towards us. I time it perfectly, catching the crest and pulling myself up. I stand triumphant on its back, enjoying the thrill of the rush to the shore, before I notice something is wrong. The other surfer is not with me, and when I look back I can see his surfboard floating on the water. There is no sign of him. In a panic, I paddle towards it as fast I can, though it’s a struggle in the stronger current and the increased swell. Spray breaks over my head, salt water fills my mouth, causing me to retch. Ahead of me I can see a head bobbing up and down, arms flapping; then he sinks below the surface, a few feet from his surf board. My arms are hurting with the effort, my body exhausted with the battering of the waves, but I cannot abandon him. I cannot. The knowledge that I cannot abandon him, gives me a spurt of energy, shooting me forwards to the spot where I saw him go under. I dive down, eyes smarting, searching for his body in the blur of blue, green and yellow. I can’t see him, and now my lungs are gasping, so I swim to the surface, gulping huge breaths of air. I am about to dive again, when to my relief his head comes back up again. I race towards him, grabbing his torso before he can sink again, holding tight as a large wave rolls over our heads. He is heavy, gasping for breath; it is a struggle to keep hold of him, particularly in these strong currents. His board is still bobbing to the side; his leg has caught on the leash and it is too tight to disentangle out here. I tell him to lie back and he relaxes into my body – which makes it easier to keep hold of him as I backstroke towards the board. As we arrive, he has the sense to grab it and I can push him up. Soon he is lying on top, red faced, worn out from the effort to survive; for a brief second I wonder whether it was worth it, for either of us. Then practicalities intervene: we are cold, tired, we need to get back to land.

Thankfully, once he has a chance to recover his face begins to lose its purple flush; he is able to raise himself to a paddling position. I give him a push in the right direction, before striking out for my own board. I mount it and follow in his wake as he begins to paddle, first tentatively, then with more strength and purpose. At last we reach the shallows, where we slip off, wavelets splashing around our feet. He staggers to the edge of the beach, trailing the surfboard behind him, before sitting in the wet sand. The cord has tightened with the struggle; it takes both of us to loosen it, and wrest the rope off. He is left with an indented mark all the way around his ankle which he rubs ruefully.

‘Thanks. Thought I was going to drown for a minute …’ He grins, ‘Ironic, considering.’

‘Considering.’ I return his grin. ‘I’m Poppy,’

‘I know. I saw your post. Yan.’

‘You’re the one who replied? I thought you might be joking.’

‘It’s like you said … There’s no point hanging around, we might as well make the most of what’s left.’

I am so happy that someone read my post that I smile broadly, immediately regretting it when his returning smile is accompanied by a look I find all too familiar. My ‘puppies’ look’, Seren used to call it, in honour of a long chain of men whose crushes developed within minutes of meeting me. I never quite understood it as I never intended to give them any encouragement. Seren thought it was a combination of having big breasts and smiling too much. Perhaps she was right, but I’d discovered by then that people trusted me when I smiled, and being penniless and parentless, I’d always had more need than she for allies. Back then it was easy enough to deter the puppies with a casual kiss for her and an arm around her shoulder. I have long since lost that defence, and somehow I always find words fail me. I am left with deflection, so I suggest we go back to my car for the rest of the gear. Thankfully, he is happy to agree, and by the time we reach the car park, the doe eyes have gone. Which is a relief. Because now he is here, it is a physical reminder to me that I haven’t imagined this whole thing. There really are only a few hours left. The knowledge is terrifying enough without any of the complications unwanted attention can bring. What I need tonight, is a friend, someone who can help me make it through the dark. Watching Yan lift the furniture out of the car as he chats away cheerfully, I think he might be able to do that, which is a comfort, because comfort is what we both need.