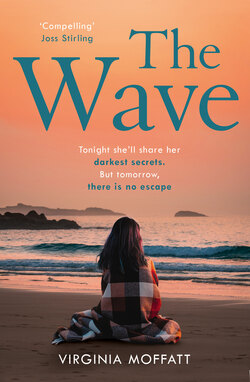

Читать книгу The Wave - Virginia Moffatt - Страница 14

Nikki

ОглавлениеThe sun streaming through the curtains wakes me, but it takes a while for me to come to my senses. I feel hot, my body sluggish. What time is it? I only turned over for a quick doze at nine, thinking the street noises would wake me, but I’d forgotten I switched rooms last night after being freaked out by noises in the graveyard. The back bedroom is much quieter and so I have slept on undisturbed. Shit, it’s nearly one o’clock. I’ll have to get a move on if I am going to make my train.

As I draw the curtains I remember I promised Mum and Dad that I would mow the lawn. They’ll be pretty pissed when they get back – they’re so proud of their English country garden, it makes them feel like true Brits. They’ll be mad as hell when they see the tangle of brambles smothering their rose bushes and the grass almost as high, but I couldn’t help it. I’ve been doing lates all week and just haven’t had the energy. I will scribble them a note and hopefully they’ll ask my brother, Ifechi or Ginika, my sister to do it and will be over it by the time I’m back.

I take my scarf off, rub my hair with pomegranate oil and comb it through, tying it in a pony-tail to keep it off my neck. I’m hot and sticky and still smell of chip fat. There’s no time to shower; instead, I have a quick wash, moisturize and hope the coconut oil masks the smell. I throw on blue shorts and a lilac T-shirt, stuff clothes and beauty products in my bag and rush downstairs. I’m hungry, but there’s no time to eat either, so I grab an apple and a packet of crisps. I’ll just have to hope the train’s buffet is well stocked.

I am out of the house and down the alley in no time. There is no one much about; they’re probably all at the beach. I speed right at the corner, then left. It is only as I’m approaching the Longboat Inn that I notice something is wrong. The road ahead is jammed with cars in both directions and the station is densely packed with people, all the way through the car park round to the harbour. The queue spills out into the road and stretches back alongside the railway tracks down to the pub. What is going on? I fight my way through the crowd and join the end of the line. My train is in the station, but I can see it is already full; I doubt I’ll even get on the next one. I find a place behind two middle-aged white men. One is hunched, with a worried expression on his face, the other rocks back and forwards besides him. I take off my backpack and place it on the ground.

‘What’s up?’

‘Eh?’ The worried man is about to respond, when the other one, starts saying and over again, ‘The wave, the wave, the wave,’ as he rocks. My neighbour turns to him in soothing tones, ‘It’s OK, Paul. We’re getting on the train and we’ll be fine.’

‘Will we, Peter? Will we, will we?’

‘Of course. Why don’t you get your DS out and play a bit of Pokemon?’ Paul acquiesces. He pulls the DS from his pocket. It has an instant calming effect; he sits down on a suitcase and is soon absorbed in his game. The worried-looking man turns back to me. ‘My brother. Gets a bit anxious. He’s autistic, you see. What did you say?’

‘What’s happening?’

‘Haven’t you seen the news?’ I shake my head. He shows me the headlines on his phone. A volcano collapse, a megatsunami, and the whole of Cornwall under water. I can’t take it in. It explains the crowds, but it just doesn’t seem possible looking at the calm, sparkling sea. I scroll through my phone to find the story is everywhere. My inbox is full of messages. Nikki it’s Stef, are you OK? Niks it’s Max, ring me. Nikki darling it’s Mum, where are you? Even my little sister Ginika has texted, though I note wryly Ifechi hasn’t bothered. There are too many to respond to, and I don’t know what to say anyway. But I reply to Mum telling her I’m waiting for a train, and send Ginika a message to say I’m having an adventure. After that I sink to the ground, my legs shaking. If only I hadn’t been so tired last night. If only I’d stuck to my original plan and travelled through the night after work. I’d be with Alice in Manchester, glad of my lucky escape. That last-minute decision to have a lie-in has come at quite a cost.

‘Are you all right?’ Peter says as the train pulls out of the station. I’d have hoped it might mean the queue would move forward but it doesn’t shift.

‘What do you think?’

‘Sorry, stupid question. But it’s too early to panic. It’s only an hour and a half to Plymouth. They’re bound to lay on extra trains, aren’t they?’

He’s being kind and I can see he is trying to reassure himself as much as anything; but I’m not so sure. They have struggled with staffing on this line lately, and what if there isn’t enough rolling stock? I have too many questions, and I am so hungry and thirsty I can’t think. I open the pack of crisps, wishing I had brought a drink. I daren’t go into the shop in case I lose my place. The sun is hot and I feel dizzy. I close my eyes. There is something of the heat, the stink of petrol, the beeping horns that reminds my first trip to Lagos when I was eight. I was such a pampered child! What a fuss I’d made about everything, the crowded streets, the dust, the lack of amenities in my grandparents’ house. It was a wonder, Dad would say in later years, that they hadn’t packed me on the first flight home.

The sound of an engine makes me open my eyes as a sleek red train comes into view. The crowd cheers as it arrives at the station until they spot the number of carriages. Only six! They should be laying on twice that many. There are shouts from the passengers on the platform who rush forward as the railway guards try and keep control. Gradually the train fills and the queue moves forward. By the time it is ready to depart, we have moved a few hundred yards further up. It’s not far, but it is progress. I eat the apple slowly. With any luck, I’ll be away by six. The train leaves. Hopefully the next one will be along soon. But nothing comes and there is no information when I check the website. I try to calm my nerves by listening to Rihanna, try to imagine this is all over and I’m out of the danger zone heading to Manchester. It works for a while, but then I sense the mood of the crowd change. I take off my headphones and catch the tail end of an announcement over the tannoy. I cannot make out the words, but ahead of us there are angry murmurs that quickly become shouts. The rumour passes along the line until it reaches us. Trains are needed for evacuation of the northern coasts. There will be no trains from Penzance after five.

Two more trains. That means only two more trains. Everyone is making the same calculation and suddenly the patience of the queue is exhausted. People rush forward from every angle, jumping in the road between cars to get ahead of their neighbours. Everyone is yelling and ahead of me I can see a couple of fights breaking out. Peter pulls his brother to one side, clearly intending to wait it out, but I can’t see any point in staying here. I jump to my feet, pushing against the throng surging forward, fighting my way down the road until, at last, I am clear. Now what? Hitch a lift? It seems the only option left. I walk up to the junction for the A30. The road ahead is filled with traffic. My heart sinks; this looks as bad as the trains. The cars are moving slowly, but none seems inclined to stop. I check my phone; I’m thirsty. I really wish I’d brought a drink with me. To distract myself, I scroll through Facebook, looking for some signs of hope that people are getting out. But all I find is a post that is being shared widely. A woman called Poppy inviting people down to Dowetha Cove because she thinks we can’t get away. It seems defeatist, but then, looking at the road ahead, maybe she has a point.

This is ridiculous. I can’t believe escape isn’t possible, that someone won’t stop for me. Right on cue a car pulls up and the driver sticks out his head. He is older than me; I notice dark wavy hair, kind eyes. Not another beautiful white boy. I swore off them after Patrick. But then he smiles at me and, despite myself, I smile right back.

‘I’m James,’ he says as I slip into the passenger seat.

‘Nikki.’ I kick off my shoes and somehow, white boy or not, I feel immediately at ease. He offers water when I ask and is interested in me and interesting to listen to. If I don’t think too much, I can continue to pretend this is just an ordinary summer afternoon. That I have just met a man who might be worth a bit of time and effort. I’ve always been quite good at telling stories, and this one is a reassuring one. I am happy, I am safe. Good times lie ahead.

Handsome white boy is as good as I am at keeping it light and the hour passes swiftly, particularly once I discover he was the one to send a prize arsehole packing the other week. Even so I can’t help noticing we’re not moving as fast as we’d like. Every time there is a break in the conversation, I try not to glance at my phone which is full of news of bad traffic. I try not to think about how slowly we are travelling or how long it will take us to get anywhere. It is when we reach the top of the hill that I cannot stop pretending. The traffic is almost stationary for miles ahead. The radio and James’s satnav confirm it. We cannot get out.

I turn away from him. Despite our instant camaraderie, I don’t feel able to show him my feelings yet. I gaze out of the window again at the sea, the beautiful, calm, perilous sea. The sea that will kill us tomorrow. How can that be possible? All my plans, my dreams of living in Paris, of working as an interpreter for the UN, gone in a flash. And my family. What can I say to my parents? To Ifechi and Ginika? Being a teenager is hard enough. How can I do this to them? I think again about that post on Facebook, the thought that if there’s no escape, spending time with others, having fun, might be better than sitting in a hot car going nowhere.

It turns out that James knows about the woman on the beach too; his friend Yan is already there. The thought hangs in the air that we might turn back and join them but we don’t say anything, and when the van in front pulls off, James drives on as if we are going to continue. But shortly after he stops. We look at each other, though we don’t say a word we both know what the other is thinking. James indicates right and turns the car around to join the last stragglers driving to Penzance in search of a train. As we pass the cars driving north, I can see the astonishment on the passengers’ faces. I’m astonished, too, but the die is cast. I was dead before I even woke up this morning. This is the only option left to me now and I am going to take it.