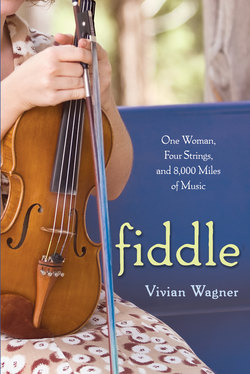

Читать книгу Fiddle: - Vivian Wagner - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3 The Fiddle Maker

ОглавлениеOnce home, I couldn’t put the thought of that fiddle out of my head. I dreamed of those ram’s eyes, daring me to do something, though I didn’t know what. That fiddle struck a chord deep within me. It was a challenge, a promise, and a mystery, all wrapped into one. I wondered about Copper Hill, Virginia. I wanted, more than anything, to find the man who had made that fiddle. I Googled Arthur Conner and tracked down his phone number. Then, partly just to have an excuse to call him and arrange a visit, I queried the magazine Bluegrass Unlimited about doing a profile story about Conner and his fiddles. The magazine’s editor agreed to look at the story on spec, and that was enough for me, since it gave me a reason to give Conner a call and arrange a meeting. But I knew the story was just an excuse: I really wanted to meet the man who had made that beautiful fiddle. I wanted to discover its secret. To discover, perhaps, the secret of fiddling itself. It seemed, suddenly, vitally important that I pay a visit to the place where that ram’s head fiddle had been born.

When I called his number, a sweetly Southern woman’s voice answered the phone. I asked her if I could speak to Arthur Conner.

“Sure,” she said. “I think he’s in his workshop. Just a minute.”

In his workshop. Just the thought of his fiddle workshop excited me.

A few moments later a grizzled man’s voice came on the line. “Yes?” he said gruffly.

“Mr. Conner,” I said. “I’m Vivian Wagner, and I’m working on a story about you for Bluegrass Unlimited magazine. I was wondering if I could set up a time to come by and visit with you for a few hours.”

He was silent for a moment. “Bluegrass Unlimited?” he asked finally.

“Yes, sir,” I said, not sure why I was resorting to “sir.”

“Well then, I reckon you’ll have to come on out,” he said, his voice lilting. “I’ll be happy to show you what I do.”

I arranged for a family vacation down to Asheville, North Carolina, to visit some cousins of mine. On the way, I made plans for us to stop in Christiansburg, Virginia, for one night so I could drive into the mountains and meet with Conner. The Bluegrass Unlimited angle was good: at least I had a nominally work-related reason to be driving around the Blue Ridge Mountains meeting strangers.

We arrived late one afternoon at the Christiansburg Hampton Inn, in a part of town dominated by fast-food restaurants and gas stations. We checked in and took the elevator to our room.

“Who’s up for going to meet a fiddle maker with me?” knowing what the response would be.

“Not me,” said William.

“I’d rather go in the pool,” said Rose, looking at me tentatively to see if I was going to push the point. She didn’t have much of an opinion about fiddle makers, but she loved hotel pools.

“That’s okay,” I said. “You can just stay here and swim in the pool with Daddy, if you want.”

“Yeah!” they both shouted in unison. Really, they both loved hotel pools. They could go to any hotel, anywhere, even a mile from our home, and be happy just to swim in its pool.

I looked at my husband, feeling kind of awkward and apologetic, knowing this was my thing. This was my journey, my obsession. I had arranged this trip; I had dragged them all down here; they had to just put up with it.

“Do you mind staying here with them while I drive up there?” I asked. “I’ll be back in the early evening.”

“I guess,” he said. “Do what you have to do.”

I looked at him, trying to discern his mood, his perspective. But he was inscrutable. As if he had shut part of himself down.

“Thanks,” I said. “Really. Okay?”

He nodded. I got the kids into their bathing suits, and we all went down to the pool, which was surrounded by large bushes and a black cast-iron fence.

“I promise, I’ll be back by early evening,” I said. My husband waved slightly and then turned away from me to watch as the kids jumped in the pool. I waved at them, and they waved back, smiling wet smiles.

“See you kids soon!” I called. “Love you.”

As I drove past the McDonald’s, pizza places, and chain hotels, the late afternoon light spread green, gold, and copper on the hills. The road I drove up into the Blue Ridge Mountains would, according to MapQuest, change names several times: first Route 460, then South Franklin, then Pilot Road, High Rock Hill Road, Daniel’s Run Road, Hummingbird Lane, and finally Conner Road.

I tried to note each name change as I passed the occasional crooked road sign, all the time climbing higher and higher, past old log cabins and farmhouses with towers of tomatoes, past trailers set into hills cut away to reveal millennia of yellow and rustcolored rock layers, past trucks with shotgun racks and stars-and-bars bumper stickers. At last, I arrived at Conner Road, a road named after the first settlers in these parts, ancestors, I presumed, of Conner himself.

As I drove up, Conner stood in the doorway of his modest ranch house backed up against the Virginia woods, waving. He was a wizened old man, his face like a precise, wrinkled carving from the same red maple he used to make his violins. He wore a blue plaid shirt, black suspenders, khaki pants, and a tan and green cap with a fiddle embroidered on it. He had a gray beard and mustache, reddish skin, and a broad, toothy grin.

“You made it,” he called as I stepped out of the van.

“Yeah,” I said. “I just kept driving.”

“Well, that’s the way you do it,” he said, laughing a deep, scratchy, woodsy laugh.

I walked through the grass toward the house. Several large butterfly bushes heavy with purple blooms and covered with black, blue, and purple swallowtails lined the front of his house. When I approached, they flocked into the air, hovered for a moment, and then landed on nearby branches.

He led me into his home, and as my eyes gradually adjusted to the inside light, I saw wood everywhere: knotty wood paneling, a carved wooden owl gazing across the small room from his perch on a wooden mantel, and a large reddish string bass and a cello resting on a wood floor.

“This is Ilene, my wife,” he said, nodding at the kind-looking woman who stood quietly at the edge of the room. She had short gray hair, a kindly face, and sharp, sprightly blue eyes.

“Nice to meet you,” I said, shaking her hand.

She smiled. “The same,” she said. I’d find out later that she’d known Conner her entire life, growing up just down the road from him, but they’d only married recently after both of their first spouses had died.

I felt both of them looking at me, sizing me up, a feeling I’d get used to on this journey.

“Care for something to drink?” Ilene said.

“No, that’s fine,” I said, getting ready to ask Conner some questions about his fiddle making, waiting for him to sit down. But he didn’t. He stood there, watching me.

“Mind if I ask you a few questions before we begin?” he asked.

I was surprised. I’d worked as a journalist for years, but I wasn’t used to being on the other side of an interview.

“Sure,” I said.

“Well, to be honest, I could spend days talking to you about fiddles,” he said. “Guess I’m just wonderin’ what you want to know. What you already know.”

I paused. “Well,” I said. “I play violin. So I know a little already. But I’m still learning about fiddles and fiddling. I guess I want to find out everything I can about fiddles and fiddle making in a few hours.”

He studied me carefully. “Play the violin, do you?” he asked.

I nodded.

“Well, maybe later I’ll give you a little fiddle lesson,” he said.

“That would be great,” I said.

He still didn’t sit down, but he pointed at a large leather-bound book on the coffee table in front of me, with The Secrets of Stradivari printed on the front in gold.

“That’s how it all began,” he said. “Most of what I know, I learned from that book.”

He opened it and showed me diagrams of violins, with measurements for width, length, thickness of wood, and page after page of fine-print instructions.

“See?” he asked proudly, and slightly conspiratorially, as if he were letting me in on a secret. “See there? It’s all in this book.”

Conner’s workshop was in an old, white-painted and peeling schoolhouse that he bought, disassembled, and rebuilt behind his house. As the door creaked open, it took my eyes a moment to adjust to the dim light coming in from the side windows. Straight ahead, I could see a large, black cast-iron wood stove. To the right, the walls were painted blue, and there were stacks of wood of various sizes, from rough cut planks that looked like they had come directly from a tree to smaller, smooth pieces closer to violin size. These were stacked like library books on rough-hewn wooden shelves. There must have been enough wood in that storehouse to create dozens of instruments.

“I like to joke that I have plenty of firewood here,” he said, laughing. “In case I need it.”

I laughed with him, feeling that uneasy and humorous tension between just plain old wood and wood made special by its destination as a musical instrument. He picked up a plank of smooth curly red maple and showed it to me.

“This is my most valuable wood,” he said. “See the knots, the design in that wood? It comes from struggle, from fighting the elements. Curly wood is wood with a defect, wood that’s had to suffer to get where it is. It’s beautiful wood, ain’t it? It’s what I make the backs from.”

I looked at the wood, admiring its random designs and patterns drawn from struggle and hardship.

The workshop had screened windows looking out over tall, green vines and bushes, and a workbench and a stool that stood like a throne in the middle of an ordered chaos. Items filled every possible space on the workbench: a blue drill, pieces of wood, a vice, wood-handled scrapers and knives, scroll-shaped metal templates, a white ceramic mortar and pestle, a can of WD-40, a box of Band-Aids, halved plastic milk cartons filled with mysterious brown substances, a hot plate with a pan holding an old jar and a wooden spoon. On the wall hung rolls of tape, funnels, filters. An unvarnished violin dangled from the ceiling beneath skylights. In the midst of the cacophony of tools and wood wafted a complicated smell made up of varnish, dust, and the sharp, sweet scent of raw wood.

“The sound of the fiddle, it all has to do with the wood that it’s made from,” he explained. “The cells, the sap tubes, they all create the instrument’s voice. My method, which is secret, keeps those sap tubes open so they can transmit and amplify the music.”

I nodded, thinking as he talked about how intimately connected to the natural world was the violin. The wood, the horsehair bow, the rosin made from the sap of trees, the catgut traditionally used in the strings: all of it is drawn directly from the wilderness.

“This is my sanity here,” he said, sweeping his arms and eyes across his shop. At first glance it looked like any other cluttered wood shop, with its saws and tools and dust. But as my eyes adjusted to the light streaming in through the Plexiglas skylights, I looked closely and saw a half-carved scroll among the tools, a nearly complete violin hanging above me, and more diagrams and books about violin design scattered on a nearby table.

He joked that his wife Ilene threatened to clean up his mess, but he said in fact he knew exactly where everything was.

“See, I got a place for everything,” he said, picking up a wood gouge and putting it on the shelf. “This goes here, and this goes right there.”

He sat on the stool, looking slightly flustered in the midst of his tools, as if he weren’t sure where to begin.

Conner picked up a piece of red maple carved into the rough shape of the back of a violin and showed me how he whittled away the sides, the middle, measuring it as he went to see that his thicknesses are correct. We went through his shop like this, jumping from step to step, sometimes forward, sometimes backward. He had too much to tell me and not enough time. As he talked, I tried to piece together how he made fiddles from start to finish.

He said he begins with lengths of red maple and spruce, which he whittles down into rough fiddle shapes: the front, with its f-holes; the back, with its many different thicknesses to help channel the sound; the sides; the neck. He makes the back and sides and neck from curly maple, which gives the instrument the typical flared finish. The top is made from spruce, and the finger board and pegs are made from ebony.

Since he was a young boy, Conner said, he had honed his skills as a woodcarver, whittling pieces of wood with a little pocket-knife into tops, guns, gravel-shooters, and other toys. His mom died when he was ten years old, and his father didn’t earn much money, so if young Arthur wanted toys, he had to make them. Now he uses those skills to carve the wood of fiddles. He focuses much of his artistic efforts on the scroll, which often becomes his trademark ram or cougar head. He assembles the pieces, shaping them and gluing them together, adding the fingerboard and pegs. After he finishes the body of the violin, he coats the instrument with a mixture of borax and lye, which he makes by running water through ashes in an upside down plastic container on his wall. He learned about this mixture from The Secrets of Stradivari, and he told me that it kills any bugs that threaten to eat the wood and cleans out the sap from the wood tubes—giving the violin its resonance.

Conner then coats the wood with tempera, a sealant made from egg whites, and varnishes it with a homemade mixture made from bee propolis, a substance produced by bees to seal their hives. According to The Secrets of Stradivari, this same substance was used by early Italian violin makers to seal the wood. Popular stories regarding Stradivarius violins suggest that their exquisite sound comes in part from his secret varnish formula. Although some scientific analysis of the varnish on Stradivarius violins has indicated that it’s not much different from basic furniture varnishes of the time, the stories have real power for violinists and violin makers alike. Conner was thus particularly proud of his special propolis varnish recipe, which his beekeeping neighbor, Danny, made for him. Danny’s a chemist by profession, and he created a secret recipe just for Conner, mixing the sticky substance bees produce to seal their wooden hives with other chemicals. Conner said that he didn’t know the precise ingredients in this mixture, but he trusted Danny’s recipe.

“What’s in it, besides bee propolis?” I asked.

He eyed me carefully. “Think you could tell if you smelled it?”

I shrugged. “I guess I’d have to try.”

He unplugged a small glass container holding dark brownish green liquid, and let me smell. I said it smelled like bees-wax, and mint, and wood sap, and maybe turpentine. It smelled like something else that I didn’t tell him, though. Somehow, it smelled faintly like the Blue Ridge Mountains.

As the late afternoon light stretched across the green hills and woods, we went back to his house.

“Thanks so much for your time,” I said.

“Wait a minute,” he said. “You’re not going anywhere yet.”

He pulled out a case containing a set of his fiddles, one with five strings, and one with four. He handed me the four-string and took the five-string himself.

“It’s time to play some fiddle,” he said, smiling. “Show me what you can do.”

Once again I froze, trying to remember some of the songs I’d been learning. I started playing a halfhearted rendition of “Ida Red,” with its simple droning double-stops that I’d started learning with Angela.

Conner shook his head.

“I see you’re trying to play old-time fiddle,” he said. “But you know, that’s not the way it’s done. It’s all in the timing. And the foot tapping. Can you tap your foot?”

As I began to tap, he belted out a soft and fast old-time version of a folk tune called “Eighth of January,” which he said was about the Battle of New Orleans. He bowed in quick motions, back and forth, in a distinctive old-time way that I’d heard on recordings but couldn’t quite figure out how to imitate. I tried to play along, but my tone sounded all wrong, too melodic, like the tone of a classical violinist. As he played the tune over and over, though, I began to get the hang of it a little, began to sense how the notes fit together in a pattern unlike any classical violin piece, began to understand how to make the continual droning sound of old-time fiddle without simply sounding weak. He was right; it was all in the timing, and in the foot tapping. It might have had something to do with the way he held the bow and the instrument, too, though I couldn’t quite tell. He played a few other songs, such as “Alabama Girls” and “Rabbit Sittin’ in the Cornfence,” as well as a strange version of “Greensleeves” that was, as best as I could tell, in C major. Mostly, I listened, trying to join in as I could.

“Well, you keep practicing,” he said, eyeing me skeptically and taking the fiddle from my hands. The ebony eyes of the fiddle’s ram’s head seemed hard and inscrutable. “You’ll get there.”

I have to admit, I’d been hoping he’d like my playing. He’d told me when I arrived, after all, that when good fiddlers visit him, they might leave with a fiddle. I’d been thinking I might be leaving with an instrument, but as I looked at him, I knew I wouldn’t.

“Yeah, I’ll keep trying,” I said.

“That’s how you do it,” he said, laughing his grizzly laugh as he put both fiddles away in their double case, carefully nestling the rams’ head scrolls in their places. “That’s how you do it.”