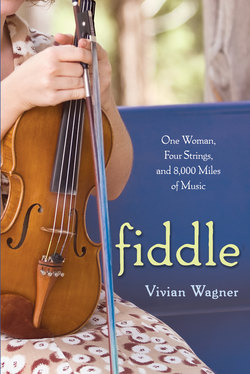

Читать книгу Fiddle: - Vivian Wagner - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1 Learning to Play

ОглавлениеMy mom always wanted me to play fiddle. She’d grown up poor, the daughter of a long line of pioneers with Scots-Irish and German roots who finally settled in California’s Central Valley in the 1940s. As she packed tomatoes into crates and milked goats, she listened to transistor radios playing country and bluegrass music, which often as not featured fiddling. After high school she left farm country for Los Angeles, worked her way through college, and earned degrees in math and statistics. On her climb upward, however, she took with her some of the culture ingrained since childhood. Growing tomatoes. Putting up jam. Humming tunes. And liking fiddle music.

“You’re always playing Bach and Beethoven,” she’d say to me when I was in high school. “Why don’t you play some fiddle tunes?”

She pronounced the “ch” and the “th” as if she’d never studied advanced German at UCLA. But somehow, pronouncing the names of German composers wrong was almost a matter of principle for her.

She did this with other words, too. Like “wash.” One time a friend made fun of how I said warsh instead of wash, and immediately I realized where this came from: my mom.

So that evening over dinner, when Mom said something about warshing the clothes, I corrected her.

“It’s wash, Mom,” I said with all the superiority I could muster as a nine-year-old.

Her response surprised me. Instead of thanking me for my brilliance and changing her ways immediately, she looked at me, long and hard, her pale blue eyes like thin ice.

Finally, she said, “That’s how I say it, and that’s how it’s supposed to be: warsh.”

And that was the end of it.

The fact is, though, I didn’t know anything about fiddling. I’d never heard it, and if Mom liked it, well, then, it must have been something pretty okie. That’s what my dad often called my mom, teasingly. Okie. I never knew quite what it meant, but it sounded pretty bad. Whatever it was, I didn’t want to be it.

And anyway, I was a violinist.

Some part of me wanted to please my mom, though, to play something that she might like. So one day at the music store with my dad, I saw some fiddle books: Bluegrass Fiddle Styles, by Stacy Phillips and Kenny Kosek, and The Fiddle Book by Marion Thede. I asked him if he could buy them for me, thinking it might make my mom happy if I tried to play from them. Reluctantly, he agreed. He used his own allowance money, which came from his travel reimbursement checks at work, and paid $15 in cash for the two books.

When we got home, I showed my mom the books.

“So let’s hear some,” she said. “Go ahead and play.”

“I’ll need to practice first,” I said, shy and unsure of myself or fiddle music. I tried to make sense of the strange cross-tunings and notations in these books. I tried to understand how to play “Cotton-Eyed Joe,” “Old Dan Tucker,” and “Tom and Jerry.” But I didn’t have any recordings of fiddle music, didn’t know what it sounded like, and couldn’t make much sense of this music. It all seemed so foreign to me, and I couldn’t compare it to the watered-down classical music I’d been learning in lessons and in the school orchestra. So the books stayed on the shelf in my bedroom, unused and forgotten, and I never did play any of those tunes for my mom.

My love of violin had started when I was seven and first heard Elaine Moreno playing. After school at the Navy ranch house of my babysitter, Mrs. Moreno, I’d sit on the couch and listen to her teenage daughter practice. Elaine would swing her thick, glossy black hair through the air, twirling across the living room floor, smiling, at one with the music.

Whatever magic she possessed, I wanted.

So in fourth grade, when my teacher sent home a little pink mimeographed slip with information about the school orchestra, I begged my mom to let me play violin. She agreed, and I joined, dutifully carrying my rental violin back and forth to school, adding my interpretation of “Hot Cross Buns” and “Jingle Bells” to the cacophony of beginning violins, violas, and cellos.

During the summers after fourth and fifth grade, my mom signed me up for lessons with Miss Blakesley, who lived in the California desert town of Ridgecrest, where I went to school, in a trailer cluttered with music books, magazines, houseplants, and cat toys. In her living room window, an air conditioner kept up a continual, comforting whir. She taught the Suzuki violin method, starting with that anthem of beginning violinists everywhere, “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” and its variations: taka-taka-ta-ka, and taka-taka-taka-taka. Eventually we moved on to “Lightly Row” and “The Happy Farmer.” Shinichi Suzuki developed the Suzuki method in Japan as a way to teach children music through immersion, saturation, and ear training, and it emphasized recitals and group playing. Miss Blakesley arranged regular, Suzuki-style recitals for her beginning students to play their pieces together in neat rows, but she also used the Suzuki music books to teach her students how to read music. And in her weekly lessons, we worked slowly but surely through Suzuki Book I.

I learned one main thing in these early lessons: violin is hard. To begin with, there’s the way you hold the instrument and the way you hold the bow. Hold either one wrong, and your teacher will tell you, in no uncertain terms, that you will never be able to play beautiful music. So, wanting to play beautiful music, you focus on bending your thumb on the bow just so, placing your pinky just so, holding your left wrist just so, and bending your fingers onto the fingerboard just so. As soon as you focus on one, though, another inevitably goes out of whack. Bend your right thumb, and your left wrist creeps up. Hold your left wrist down, and your left fingers flatten on the strings, your right thumb straightens, and your right pinky flies off into space.

All this happens before there’s any consideration of sound, let alone music. That comes lessons and lessons later, when you work on tone, and pitch, and the pressure of the bow on the strings, and the running of the bow hairs parallel to the bridge, and all the other thousand things that you must learn to do if you ever want to make beautiful music.

I played and played, most of the time getting it wrong, but after every lesson, getting it a little more right. Miss Blakesley gave me a sticker for each piece I completed, and I especially liked the strawberry scratch-and-sniff ones. My sister, Ann, who took lessons with me, favored plum. She liked it so much that she peeled one off her practice sheet and stuck it on the chin rest of her tiny one-tenth-size violin, where it remains to this day, announcing its cheerful message of “Great job!,” the paper worn thin but still smelling faintly fruity. Ann’s lesson came before mine. While she played, I waited, sitting on the brown plaid couch, reading a book, looking at an old issue of Reader’s Digest, or just gazing out the window at the trailer next door. Ann often got frustrated, and Miss Blakesley would end the lesson early, looking over at me exasperatedly. But I sympathized with my sister. Though five years older, and a bit more patient, I knew.

Violin was hard.

Really hard.

Eventually, Ann gave up violin for cello. I kept with it, though, taking lessons, going to orchestra practice, and gradually improving. In junior high and high school, my friends and I listened to Journey, The Cars, The Who, and Pink Floyd, but secretly, I really loved the music we played in orchestra. I loved Bach, Corelli, Barber, Stravinsky. In high school, I worked my way up from fourth chair, to third, to second, and finally, in my senior year, to concert mistress. I loved how the music flowed through me and around me, and I relished orchestra’s peculiar combination of competition and art. Orchestra was my home, my second family. My best friend, Michele, played cello, and we hung around each other all the time, before, during, and after orchestra practice, our friendship growing out of our shared love of orchestra.

I grew up on land my parents had bought in the early 1970s in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, about thirty miles from Ridgecrest, where I went to school. On weekends at home, I liked to take my violin down by the creek, prop a green and off-white book of Bach’s unaccompanied violin sonatas up on a rough granite boulder, and play. My music echoed through the canyon, into the wilderness beyond. The sun heated the wood of my violin, and I smelled the rosin on my bow, which was the same smell as the pitch from the piñon trees that covered the mountains by our house, pitch that covered my hands with dark splotches when Ann and I searched for piñon nuts, digging them out of the small, stiff cones. The violin’s wood smelled like the pine, maple, and willow trees all around me. And the horsehair bow, warmed in the sun, smelled like the tail of Trixie, our horse, when she stood in the sun in the meadow, swishing at flies. Playing my violin there by the creek brought all these elements of my life together, and at the same time it took me beyond them, into a realm of pure music, pure light, pure beauty.

It was such difficult music, though. Bach’s unaccompanied sonatas have triple and quadruple stops, three or four notes played at a time in impossibly complex chords, sixteenth-and thirty-second notes swirling like a raging, black river across the page. I loved those pieces so much that I’d try, over and over, to play them, knowing exactly what I wanted the music to sound like. I knew my interpretation was only approximate, but I kept trying.

Sometimes, when Bach got too hard, my eyes wandered from the page, and I’d play new notes and melodies, improvising on his basic melodies and chords. My notes, now my truly mine, wandered on the pine-scented air through the canyon, echoing off the granite cliffs.

As a freshman at UC Irvine, I signed up for orchestra, which allowed me to receive free private lessons with a violin professor. At my first lesson, the kindly looking, white-haired professor asked me to play something for him. I brought out my book of beloved Bach sonatas, placing it tentatively on the black music stand next to his wooden shelf heavy with theory and history books. I turned to a movement in Sonata IV called “Ciaccona,” one of the most beautiful, and most difficult, pieces in the whole Bach repertoire. I’d never really mastered any of these sonatas, and out in the woods, by my home, that didn’t matter. But here, with a real violin professor, it did.

As I played, I put everything I had—my heart, my soul, my whole body—into the music. I must really be impressing him, I thought. I swayed and strained, yearning for the music I knew Bach intended. I was so deeply involved in my interpretation of Bach’s bewildering beauty that it took me a moment to feel the professor’s hand tapping my shoulder.

“Okay, okay,” he said. “That’s fine now. Okay.”

He spoke in the tones one uses to comfort an accident victim.

“That’s a difficult piece for you, no?” he said.

I nodded meekly.

“And I see that you love it very much.”

I nodded again in vigorous agreement, not quite seeing where he was going with this.

“But you shouldn’t play it.”

I stared at him, aghast. Didn’t he hear what I had been playing? The beautiful music? Bach, for God’s sake? The “Ciaccona”? What didn’t he understand? What kind of professor was he, anyway?

“For you, it’s too hard,” he went on coldly, methodically, as if diagnosing the probable cause of death in a cadaver. “You need to work on technique. You need to work on skills. And I don’t think that piece is what you need to work on now.”

I went back for a few more lessons with him, and I stayed in orchestra until the end of the semester. But I felt defeated, and before long I put my violin away and didn’t crack open its case for many years.

I studied English in college and moved to Ohio for graduate school at Ohio State. I met a lovely twenty-one-year-old boy in Larry’s Bar, near the university. He was an undergraduate student at Ohio State, and he had long, blond hair and wore a black leather jacket, looking like a cross between a biker and a choir boy. I was smitten by his sweet badness, by his intelligence, by his daringness. In one of our early conversations at Larry’s I told him I played violin, and so for our first date he arranged for us to see the Columbus Symphony, which played Tchaikovsky’s “Serenade for Strings” and Vivaldi’s “Spring.” We dated for a few months, and then, impulsively, we got married one cold January day at the downtown courthouse. We were young, and we had no clear sense of what we were doing or why. I’d left just about everything—my childhood, my family, my past—behind in California. In fact, one of the few things I had brought with me from childhood was my violin. My instrument had accompanied me all the way to Ohio, crammed with my books and Apple computer into my Mustang, and it would continue to accompany me into the future. I didn’t often play it, but I kept it with me, a constant companion.

I saw marriage, even to a relative stranger, as a way to bring stability to my life. A way to set up a new home in this distant land. A way to grow up. Though we barely knew each other when we married, over time we became close friends and partners. We worked our way through graduate school, eventually moving to Illinois to get our PhDs. Just as we were finishing our degrees, he got a job at Muskingum College in New Concord, Ohio. Neither of us had ever heard of the college, which has since changed its name to Muskingum University, or of New Concord, but we were game for anything. He accepted the job, and we made plans to move and start a new phase of our life.

Before we moved there, I studied the map of southeastern Ohio, looking at the crooked roads indicating hills, the names of villages and towns dotting the landscape: Norwich, Zanesville, Cambridge, Roseville, Crooksville, Barnesville. Southeastern Ohio is just on the edges of Appalachia, in the hilly, unglaciated part of the state. I read about the area’s history, how it had been strip-mined throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, how it was the poorest part of the state, how it was classified as Appalachia by the federal government.

Driving our U-Haul truck from Illinois, I was struck once we got past Columbus by the beauty of the green, rolling hills that seemed to go on forever; the picturesque farm houses and grazing cattle; the winding rural roads; the village with its main street, gas station, grocery store, hardware store, and post office. We bought a little white and blue-shuttered house on the western edge of the village, on a narrow street that climbed steeply up from Route 40, or the Old National Road, which cuts through the village.

In the first couple of years of living in New Concord, we had two children, William and Rose, and I stayed home with them, doing freelance writing in my basement office while my husband taught at the college. The village seemed like a perfect place to raise a family, a perfect place to call our home.

It didn’t take me long to realize, though, that I was an outsider in southeastern Ohio. Down at Shegog’s IGA, the grocery store on Main Street, everyone seemed to know everyone else by name. People in the village spoke with rough, Appalachian accents, and they viewed newcomers with wariness and suspicion. The few people I got to know in those early years were affiliated with the college, but at that time most of the college faculty were middle-aged or older, so I felt just about as isolated from them as I did from the longtime residents of the village. I felt like I didn’t really know this place. And I began to realize that no matter how long I lived there, I’d never be from ’round here.

I stayed home with the kids, keeping to myself, tending to their needs. I tried to make a home in a place that felt like a wilderness outpost. I shopped at Shegog’s; I went to the post office; I bought supplies at the hardware store, pushing first one child and then the other around the village in a dark blue Graco stroller. I tried my best to make a happy, stable home for our family. The kind of home I’d always wanted. The home I’d been wanting ever since we married in the courthouse on that January day so many years before.

Once the kids got a little older, I began teaching journalism at the college, happy to finally have a full-time job, a growing career. But I always had a nagging suspicion that somehow, I didn’t belong to the landscape, to the culture. That I wasn’t a native. Something about the home, and the life we were building, always felt temporary. There’s a wall between those who live in Appalachia and those who move there, and I began to think that perhaps that wall would never be breached.

Occasionally, over the years, I pulled out my violin, rosined up my bow, and played in concerts with the Southeastern Ohio Symphony Orchestra or Messiah performances at a church in Zanesville. But most of the time my trusty old violin stayed in my closet, leaning up against the wall, waiting for those times, few and far between, when I opened its case, rosined up the bow, and took it for a spin.

For the last years of her life, my mom was sick with emphysema, bed bound, hooked up to oxygen, and close to death. One summer night, about nine years after we moved to New Concord, she slipped into a coma and died.

Reeling with grief, confused, and alone, I flew back to the California desert to bury my mom. While arranging the funeral, Ann and I came up with the idea of playing some kind of music for the service. Though we could barely hold ourselves together enough to organize the funeral and write up an obituary, let alone perform, we told ourselves it would be a fitting tribute to her, since she had insisted on all those music lessons, come to all of our school concerts, and encouraged us in our music.

Perhaps we suspected, though, that playing through the funeral would help us cope. Playing, we could focus on notes, and not thoughts. Playing, we’d have rhythm and pitch and phrasing as a grammar for our grief. Grief was startlingly, frighteningly new, but music was a language we’d spent our lifetimes learning.

We had both left our instruments at home, though. We hadn’t even considered bringing them. So, the day before the funeral we sat in the Starbucks on China Lake Boulevard, drinking caramel frappuccinos, watching the traffic, looking at the tumbleweeds piled in the desert lot by the pizza place across the street, considering our options. We talked of calling an old music teacher. We debated looking up friends who had played in orchestra with us. Finally, though, we called a music store and asked about rentals. I explained to the man who answered the phone that we wanted to rent a cello and a violin for a few days so we could practice and then perform at our mom’s funeral.

“We don’t do short-term rentals,” he said.

“Oh,” I said, my voice trailing off. “Okay.”

I heard him pause and breathe on the other end of the line.

“Usually,” he said. “We usually don’t do short-term rentals. But I’ll let you do it for this.”

“Thank you so much,” I said. “You don’t know how much this means to us.”

“That’s fine,” he said. “Just come down to the store.”

So we did, and he pulled out new, shiny instruments for us, set up music stands, and told us we could play as long as we wanted, right there in the middle of the store. Ann and I looked at each other, unable to believe his generosity, offering us both rental instruments and a practice space.

We sat in the middle of the music store and played. We played Bach and Mozart, hymns and popular songs. We played that old high school orchestra standby that we knew so well, Pachelbel’s Canon. We pulled out a wedding songbook from the music store’s shelf, since we couldn’t find a funeral songbook, and we played love songs from its contents. Ann and I played until our fingers hurt, until we couldn’t play anymore. Finally, exhausted and spent, we decided we’d play the Pachelbel, and one of the wedding songs. And at the end, Ann would play “Danny Boy,” because Mom used to like it when she played that song.

On the morning of the funeral, out in the desert cemetery under a tent, we set up our instruments near the end of Mom’s pine coffin, which had purple, blue, and white wildflowers strewn on top. Surrounded by the hot, bright desert, in front of Dad and a few of my parents’ friends, we played. Just like we’d practiced: Pachelbel, love song, “Danny Boy.” Somehow, we got through it. Somehow, we stayed with the program. We played, and then we spoke at the little wooden podium, and then we sat back down and played some more. And as we played, our notes resonated through the dry desert heat, across the sand, and out toward the distant volcanic hills.

I lined up violin lessons for the kids when William was seven and Rose was five, with a young woman named Angela. She gave lessons on Thursday afternoons in the basement of St. Benedict’s Catholic Church in Cambridge, a town just east of New Concord. I rented a violin for William, and Rose played the same tenth-size violin Ann had played many years before. After a few months, Rose insisted that violin was just too hard, and she decided to quit. William, though, stuck with it.

His lessons with Angela continued for a couple of years, once a week, every week, William marching through the Suzuki books just like I had. His lessons were much like my own had been: long, difficult, and repetitive. It takes a long time to make anything like music on the violin. He worked hard at it, though, his blond head bobbing up and down while he stretched his fingers to play the notes. Some days he’d get frustrated, and many days in between lessons he didn’t want to practice. He seemed to want to continue the lessons, though, so I kept taking him. During his lessons, Rose and I sat on little folding chairs off to the side. She’d color pictures, and I’d read a book or absentmindedly stare at the scuffed, cracked linoleum.

One day, though, the year after my mom died, and the summer I turned forty, something happened that brought me to attention.

“Want to learn some fiddle?” I heard her ask William, a hint of Appalachian lilt in her voice. She tossed her straight brown hair back, looking at him brightly, defiantly.

“Sure,” he said. “I guess so.”

She pulled out Mel Bay’s Deluxe Fiddling Method, by Craig Duncan, a spiral-bound music book with a happy-looking man in a plaid flannel shirt fiddling on the cover.

“I have this book, and we could play a little from it,” she said. “I grew up playing fiddle with my grandpa, and I think you might like it.”

She turned to the first song in the book, “Bile Them Cabbage Down.”

“Let’s start with this one,” she said. “I’ll play it through first, and then you can try.”

She played through the little tune, with its double-stops and simple bowing pattern. And while she played, I watched and, for the first time in one of his lessons, listened.

“See?” she showed William. “It’s just second finger on the A string, and then third finger.” She played through the first few measures, and William copied her. Then a few more, and he copied again.

At the end of the lesson, while William put his violin away, I went over to give Angela her $12 check.

“I might want to learn some of that fiddling,” I said nonchalantly, noncommittally, not wanting to reveal how much, suddenly and inexplicably, I wanted to learn to play fiddle. I really wanted to learn fiddle. I wanted to fiddle more, perhaps, than William did. Fiddling suddenly seemed vitally important, even necessary, for me to learn. Perhaps it had to do with grief for my mom’s death, and with the fact that I was just starting to feel the inklings of a midlife crisis coming on. All I knew consciously, though, was that I had to learn it.

“Okay,” she said, looking at me a little strangely. “You can play along, if you want.”

And so at the next lesson, I brought along my violin. William, Angela, and I played a bit together after the Suzuki part of each lesson. I could tell William thought it kind of odd that Mom was joining in, but he seemed to take it in stride. Over a few weeks, we worked more on “Bile Them Cabbage Down,” and then progressed to “Ida Red,” “Old Joe Clark,” and my favorite, “Devil’s Dream,” a whirlwind of sixteenth notes that sounded really quite fiddle-y. At home, he and I practiced our new tunes together, and the fact that I played along seemed not to bother him. It actually seemed to make practicing more fun for him. If Mom liked playing violin, well, then, maybe he did, too.

And as I played through those fiddle tunes, something strange began to happen. My fingers running through the melodies and the double-stops, my bow scratching out centuries of folk music transcribed and simplified for beginners, I felt like I’d found something I hadn’t even known I’d lost.