Читать книгу Geochemistry and the Biosphere - Vladimir I. Vernadsky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеforeword

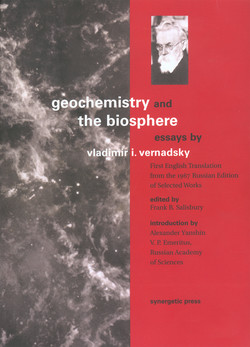

Vernadsky, Moscow 1884

Editing these two examples of Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky’s writings through three and more readings has been a most interesting and rewarding experience. Vernadsky’s writings are such an enjoyable read because there are several kinds of insights that one may gain from these two works.

There are insights into the status of Earth science and biology during the end of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, which was Vernadsky’s time – and there are several insights into Vernadsky himself.

He displayed the personality of a scientist almost from the beginning of his life. He was a truly great historian of science. He possessed a unique philosophical mind-set. He was an innovator in his field of geology and a formulator of new sciences. He had a captivating view of the future and especially of the role of humans in Earth’s geochemistry and biosphere.

During the 1880s, Vernadsky was associating with several great Russian scientists (as Academician Alexander Yanshin describes in his introduction), especially the renowned chemist, Dmitri Mendeleyev (discoverer of the Periodic Table of the Elements) and Vasilii V. Dokuchaev (the founder of soil science). Thus Vernadsky was on the cutting edge of late nineteenth century science. In 1922, after a number of moves and involvement with the revolution (he resigned from his party in 1918, feeling himself “morally incapable of participating in the civil war”), Vernadsky and his family moved via Prague to Paris, where he wrote most of The Biosphere (Biosfera), which was published in 1926 in Russian and in 1929 in French (La Biosphère). Upon arriving in France in 1922, he was asked to lecture (winter of 1922–23) on geochemistry. It is clear from the Essays on Geochemistry that much of the actual writing was done in 1933, but he must have begun his notes in 1922; presumably, the Essays were developing during this eleven-year period.

The third edition of Biosfera (the edition included here in translation) was published in 1965. When did Vernadsky prepare this third edition? Vernadsky begins his essay on the noösphere, which was new in the third edition, by noting that he was writing in 1944 during World War II. The noösphere could stand alone, and because its sections are numbered starting with #1, Vernadsky might well have expected it to stand alone. It is a logical conclusion to Biosfera, however, and also provides a most appropriate ending for this Synergetic Press volume. Because the third edition contains a considerable amount of material not in the 1926 or the 1929 editions, and because Vernadsky was writing the noösphere during World War II, we can assume that he did much editing of the 1926/1929 editions until at least 1944 and possibly until shortly before his death in 1945.

There are two aspects to the insights on the status of science during the end of the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century: the facts and numbers themselves, and what Vernadsky thought about them. Let’s consider the facts. Science has certainly progressed and changed during the past three quarters of a century. Thus, one impression during my first reading concerned how many things had changed; that is, I noted the “mistakes” and changes in viewpoint – how much Vernadsky and his contemporaries did not know. I’m afraid that I tended to be a bit critical of the facts and numbers presented in these two works. On the second reading, however, I was overwhelmed by the vast amount of knowledge of Earth’s geochemistry and the biosphere that was known in Vernadsky’s time; how much they did know! And I was especially overwhelmed by how much Vernadsky knew. The breadth of his knowledge of the science of his time is truly amazing – how could one person have so much information at his fingertips?

Nevertheless, one should be careful in reading these two volumes. One should not assume that the presented “facts” and especially the numbers would be the same today (e.g., the amount of some given element in the Earth’s crust, in the biosphere, or in the hydrosphere or atmosphere). As Vernadsky was well aware and often states, his facts and numbers were estimates of the time and would likely improve and change in response to further research. I recommend that one should be deeply impressed by the sheer quantity of information of this type that was available back then – and with Vernadsky’s ability to bring it together in these two volumes. His summary of the fields is truly a tour de force. But one should be wary of the details.

Of course, as a plant physiologist with a now out-of-date minor in geochemistry, for the most part, I could only be aware of mistakes relating to my own field. In several cases, I added footnotes pertaining to some topic that interested me (and often led me to research other sources) – or to some of Vernadsky’s terms and usages (and/or those of the translator) that I found difficult to understand, requiring much cogitation and digging into dictionaries. In addition to my footnotes (labeled with “Ed.”), the Russian editor of the third edition of The Biosphere added a number of footnotes, labeled with (Comment of the editor of the third edition). Vernadsky also added several footnotes (no label).

To give you a “heads up” before you delve into the two volumes, following are some examples of points that I had to ponder (others are presented as footnotes):

Vernadsky’s thoughts about Earth’s history might have been radically changed if he had known about the oxygen revolution that is now thought to have occurred about two billion years ago in the Precambrian. Actually, he came very close to discovering it himself (in certain iron rocks). Again and again, he states that the Earth has remained essentially the same since its formation. This cannot be the case if oxygen built up to a high level during Earth’s history – such a build-up would change many aspects of geochemistry, not to mention the functioning of the biosphere (which surely was responsible for the oxygen build-up; Vernadsky often mentions that nearly all atmospheric oxygen can only be the product of life, of photosynthesis).

Along with other scientists of his time, Vernadsky assumed that, on an area basis, ocean plankton carried on about the same photosynthesis as land plants. Since the area of the ocean is about twice that of the land, they assumed that, in total, ocean plankton photosynthesize about twice as much as do land plants. We now know that most of the oceans are “nutrient deserts,” limited in life by the absence of certain mineral nutrients, especially iron. We think that land plants account for about twice as much photosynthesis as do ocean plankton.

There is a minor matter that struck me as a plant physiologist and would-be ecologist: Vernadsky states that the total area of leaves above a given land area is about 100 times that of the area below (but also counting photosynthesizing organisms on the soil). This “leaf-area index” has now been measured many times and proves to vary from about 1 (deserts) to 11 (tropical rain forests), with a few instances going to 38 (boreal conifers). Averages are about 5 to 8 (typical of deciduous forests).

Perhaps the field that Vernadsky least understood was biochemistry. He never mentions enzymes or genes, and even in his time, the importance of enzymes was becoming known (beginning near the end of the nineteenth century). At one point he even seems to take issue with the importance of proteins (all enzymes are proteins), implying that the concept of “living proteins” is nonsense. By now, enzymes and the genes that control their syntheses are thought to be paramount in life function. Vernadsky does mention that proteins are important, but he never mentions enzymes.

My thoughts and annotations are limited by my knowledge, but an earlier edition of The Biosphere was annotated extensively by Mark A. S. McMenamin.1 I found the annotations in that edition to be most interesting and valuable. Clearly, McMenamin’s knowledge in this field goes well beyond my own.

Both Vernadsky and the translator use some words that might not be familiar to those of us who are not geologists. After much study, I added some footnotes to explain some of these terms. One of them really provided a trap for me: Vernadsky repeatedly speaks of processes, organisms, and chemicals occurring in the stratisphere. At first, being a poor speller, I tried to visualize these things taking place high in the stratosphere, but that seemed increasingly preposterous. I went to the dictionaries but could never find stratisphere. Considering related terms as well as the context in which Vernadsky used the term, it finally became clear that he was talking about the “sphere” made up of Earth’s strata – the sphere of sedimentary rocks. The term is so insidious that I would have changed it if I could have thought of a suitable synonym, but terms such as sedimentaryrockosphere just wouldn’t do, so I left stratisphere as Vernadsky used it. Be aware!

All these problems are completely secondary to Vernadsky’s main theme: The biosphere is a powerful geological force that has transformed this planet and its geochemistry in a most spectacular way. I think this must have been apparent to many of his contemporaries (e.g., the science of ecology was vibrant by his time), but there is probably no other writing produced during that time that pulls it all together as well as these two volumes do.

In his introduction, Alexander Yanshin tells how Vernadsky was fascinated by the world around him from a very early age – how he read avidly in several languages everything that he could lay hands on in his father’s large library. Thus his mind accumulated a vast amount of knowledge about the science of his time, as well as the centuries preceding.

Over the years he developed many suitable characteristics for a life of science. He was able to pull together and organize an incredible amount of information and then to apply powers of analysis that were truly phenomenal. As we might well expect, these personality talents of a great scientist led to some highly unique views, relating both to science and how it works as well as to the details of geochemistry and the biosphere. All of this becomes clear in these two volumes.

We see these ideas from the standpoint of a Russian scientist who lived both in his native land and abroad during the period of the Russian Revolution and the Stalin era – which he never mentions in these writings! That in itself provides a perceptive insight into the Russian scientific mind: Although Vernadsky was active in the politics of his day, he leaves all that behind in these writings as he concentrates on questions of the biosphere and Earth’s geochemistry.

You’ll see that Vernadsky had a tremendous drive, not only to understand the natural world, but to know those who preceded him in seeking that understanding. As he cites and describes the work of hundreds of scientists who came before him, we gain a very broad view of how our modern science has developed.

Today, many scholars who write textbooks or review a particular topic confine their interests to work done in the preceding few years, or at most, few decades. In contrast, as a historian of science, Vernadsky’s interests stretch back for a few centuries (especially the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), revealing that the twentieth century (and now the twenty-first) are not alone in producing good and valid facts and ideas. Furthermore, his admiration for those scientists of previous centuries shines through strongly. Many of us might dismiss the scientists of the age of phlogiston or a geocentric universe, or those who talked about biology and the biosphere (not yet even named!) before the importance of the cell was realized, but Vernadsky could appreciate the creativity and power of their minds and focus on the penetrating ideas that others had overlooked, bringing them to our attention and pointing out that they are reflected in our current thoughts about natural history. One notes Vernadsky’s love of history again and again in these writings, but especially in the second of his Essays on Geochemistry, in which he reviews the development of his science.

Vernadsky was a philosopher of science as well as a scientist who was concerned with how the universe functions. Some of his philosophical ideas struck me as rather strange (especially in The Biosphere) until I was gradually able to fit them into an overall context of his approach to science. At one point he rails against the reliance on mere hypotheses, insisting that the only suitable method for a scientist is the (Baconian) system of accumulating facts until empirical generalizations, as he calls them, become apparent from the data. Such hypotheses as those relating to the origin of life were “philosophical and religious” hangovers, hardly worthy of true science.

A prime example of an empirical generalization is the Periodic Table of the Elements. When enough was known about the valences and atomic masses of enough elements, it became apparent to his professor, Mendeleyev, that they obeyed a “Periodic Law,” and this law was so powerful that it predicted the existence of many more elements. These predictions were fulfilled to a great extent in Vernadsky’s time and continue right up to our time. It is noteworthy that Vernadsky was well acquainted with developing chemical theory, based on the atomic models that were only being established with the formation of quantum mechanics; indeed, most of that new science was being worked out during the time that Vernadsky was writing The Biosphere.

Although he disparages hypotheses at some points, it is clear from other discussions that he agrees with the modern scientific approach of formulating hypotheses that can be tested by suitable observations and/or experiments. Vernadsky’s way of developing empirical generalizations is essentially an inductive method, which is at the heart of most of our modern science. (Since it is impossible to observe every instance of some phenomenon, we must sample the phenomenon and then generalize that our sample is typical of the phenomenon in general. This is induction, but Vernadsky sometimes applies the term deduction to this process. Deduction deduces specific ideas from general laws.)

Vernadsky held to a substantive uniformitarianism, or at least a Slavic version of it. The uniformitarianism that we often discuss holds that the present is the key to the past – that the processes going on at present are the same processes that went on during geological history, accounting for the Earth as we see it now. But Vernadsky’s substantive uniformitarianism holds that things have always been the same: that the geology of the Earth has always been the same and that life has always existed on Earth – although he was willing to admit that it has changed by evolutionary processes over geologic time. He holds this view of Earth’s history to be one of his important empirical generalizations, but it was probably this view that caused him to overlook the evidence for the oxygen revolution.2

This view meant that he strongly opposed the suggestions of his countryman, A. I. Oparin, who in the early 1920s was proposing that life originated on an Earth with a reducing atmosphere (an idea that in modified form is now widely accepted); for Vernadsky, life simply always existed! In Vernadsky’s writings just before his death, he did accept the concept of an origin of life, but that idea does not appear in these two works.

Unfortunately, the late Alexander Yanshin at first oversold me on Vernadsky as an innovator in his field of geology and as a formulator of the “new sciences” of geochemistry and biogeochemistry. Yanshin claimed so much for Vernadsky that it put me slightly on the defensive. In the process, it made me aware of the incredible number of contributions of Vernadsky’s contemporaries and predecessors. Vernadsky quotes dozens, probably hundreds of papers on geochemistry and even biogeochemistry: estimates of the quantity of some elements in the Earth’s crust, atmosphere, or biosphere, for example. Such studies are pure geochemistry and biogeochemistry. My thought then was, how can we say that Vernadsky founded the sciences of geochemistry and biogeochemistry when this vast amount of work in these fields had already been done? Clearly, Yanshin gave Vernadsky credit for his synthesis of the ideas of these fields. This synthesis was indeed a highly original and significant contribution. (Yanshin mentions a number of other sciences as examples of Vernadsky’s synthesis; my familiarity with Vernadsky’s works – his many, many publications – is not sufficient for me to judge his contributions to those sciences.)

As Yanshin points out, Vernadsky seldom claimed that he was the first to develop a field. He gives credit for the concept of the biosphere to Eduard Suess, who published the term in 1875.3 My geochemistry textbook published in 1952 gives Vernadsky credit for the term biogeochemistry but says: “The concept of the biosphere was introduced by Lamarck [near the end of the eighteenth century]….”4 Vernadsky also mentions Lamarck as the originator of the concept but not the term. In short, for some time there have been those who realized that Earth’s organisms and the physical environment with which they are closely associated should be recognized as a very special part of this planet, but it was Vernadsky’s concept of living matter, a term that he uses over and over, that strongly emphasized the effects of life on the Earth. We only have to think of Mars and Venus to realize the impact of the biosphere on our orb.

Incidentally, I found it interesting that Vernadsky seldom if ever referred to his own laboratory or field work. He must have done much “hands-on” science, but his approach in these two volumes is that of the observer, the synthesizer, who bases most of his synthesis on the work of others.

In any case, it is clear from Yanshin’s introduction, if not from the texts themselves, that Vernadsky’s influence was great, particularly in his Russia, even as this influence was slow to penetrate to the Western world.

One of Vernadsky’s most fascinating concepts encountered near the ends of both The Essays on Geochemistry and The Biosphere, is his view of the future and especially of the role of humans in the Earth’s geochemistry and biosphere. Humans, with their science and technology, have changed and are continuing to change the nature of the biosphere. The end result will be the noösphere (from the Greek: noó(s), mind). As with the term biosphere, Vernadsky credits another author, Edouard Le Roy, with the term noösphere. Another source says that Vernadsky, Teilhard de Chardin, and Le Roy jointly invented the term in 1924. In any case, the concept of the impact of the human mind on Earth seems obvious to us and has probably been obvious to some extent to many others, especially during these years of industrialization and technology, but Vernadsky says it particularly well.

some notes on editing these manuscripts

In attempting to copy edit these manuscripts, it has not been difficult to correct matters of grammar, punctuation, and style. This was done according to established rules outlined in various style manuals. But because the manuscript with which I was asked to work was a translation, and I did not have access to the Russian original, many special problems arose. Often a word or a sentence did not sound correct to the ear of a native English speaker. Sometimes in such cases of confusion, I left the translator’s word because it sounded a bit more Russian but was still appropriate enough for easy understanding. After all, Vernadsky wrote in Russian!5

In some cases, I referred to the 1926/1929 version of The Biosphere translated by Langmuir, who was a native English speaker who also had an excellent command of Russian, French, and science. His choice of words was often very helpful to me. Mark McMenamin’s annotations in the Margulis edition were often helpful because they explained Vernadsky’s ideas or clarified various scientific ideas – sometimes confirming and sometimes rejecting my suspicions about changes that should be made in Barash’s translation. However, the 1967 Russian edition (from which the present version was translated) had many additions to the 1926 version, and sometimes my problems were in a portion of the text that did not appear in the 1926 version. Also, I had no access to another English version of The Essays on Geochemistry save for Barash’s translation.

Langmuir states that his revision of the Russian/French version was “a rather drastic one.” That is, he probably took more liberties with the language than did Barash. Hence, this version, in spite of my editing, is probably a more literal translation than is the Margulis edition – which nevertheless accurately preserved Vernadsky’s meaning, according to Langmuir.

A good example of the problems of editing a translation by a nonnative English speaker is the use of the articles “a,” “an,” and “the.” These articles do not exist in Russian, so a Russian translator translating into English must insert them where needed – a very difficult task. Hence, I considered them “fair game” – to add or delete as seemed appropriate to my ear. The rules for placement of the articles in English are tricky to say the least. Although such rules do exist, they are not easy to apply. Yet a native speaker whose ear is attuned to the language seldom uses them improperly. In my editing of this translation, I must have removed a few hundred definite articles (“the”), mostly before plural words (e.g., solar rays) or compound nouns (e.g., green living matter). I also had to add quite a few definite and indefinite articles when it seemed appropriate. I apologize if these additions or deletions were not always what they should have been.

Having just read the page proofs (my fourth time through!), I continue to be deeply impressed with the two volumes, especially for two reasons. I am still amazed by what was known by the first third of the twentieth century. Most of the important geochemical and ecological themes being discussed now are foreshadowed in these volumes. One example: I thought that perhaps Vernadsky’s time had not been aware of the potential problems, particularly global warming, posed by the rapid increase in carbon dioxide thanks to burning of fossil fuels. But there it is on pages 189-190 where Vernadsky considers the views of Arrhenius.

The breadth of Vernadsky’s knowledge of the literature of geology, geochemistry, the biosphere, the kinds of living organisms, and many other topics is simply mind boggling. I began to wonder: Could anyone alive today duplicate Vernadsky’s feat, but this time incorporating all the information that has been added to and expanded upon what was known in his time?

This work has been enjoyable as well as challenging, and it was made possible by Deborah Parrish Snyder of Synergetic Press. She has been a wonderful help and a joy to work with.

Frank B. Salisbury

Professor Emeritus of Plant Physiology

Utah State University, Salt Lake City