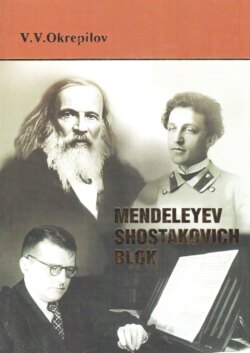

Читать книгу Mendeleyev. Shostakovich. Blok - Владимир Окрепилов, В. В. Окрепилов, Виталий Дмитриевич Доценко - Страница 3

Chapter I

Dmitry Mendeleyev

Childhood and education. First scientific achievements

ОглавлениеDmitry Ivanovich Mendeleyev was born in Tobolsk. He was the last, seventeenth child in the family of Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleyev, the director of a gymnasia and public schools of Tobolskaya province. Dmitry Mendeleyev’s grandfather was a priest in Tverskaya province. His father had also graduated from Tverskaya theological seminary. Then, however, he entered the section of philology of the Main Pedagogical Institute in Petersburg. The post of the father at the moment of birth of the last child was one of the most honourable in the town. And the remarkable intellect, high level of education and creative approach to teaching marked Ivan Pavlovich out of the teachers’ sphere.

Mother of Dmitry Ivanovich, Maria Dmitrievna Kornilyeva, came from an eminent merchants’ family. There was a legend in the family that one of the ancestors had got married for love an Orient beauty. He loved her so much that, when she had passed away, he died of grief. The niece of D. I. Mendeleyev Nadezhda Yakovlevna Kapustina-Gubkina wrote, “… A stream of the Mongolian race’s blood got into the clear Great Russian blood of Kornilyevs, and several descendants of it even have something oriental in their type…”

The clan of Kornilyevs was proud of the fact that they were the first who started to establish factories in Siberia: papery and crystal. In 1787 they established the first typography in Tobolsk and since 1789 they started editing the first newspaper in Siberia “Irtysh”, they printed books.

The big family of Mendeleyevs started living well. The nanny from serf peasants Paraskovya Pheraphontovna, who stayed in the family of Mendeleyevs till her very death, helped to look after the elder children. The father of Maria Dmitrievna, Dmitry Vasilyevich Kornilyev, also lived with them. Already in youth he was ill with a brain fever and he couldn’t work any more. Later D. I. Mendeleyev’s sister Ekaterina Kapustina remembered about the beloved grandfather like that: he was a grey-haired, thin and short old man. He was quiet, kind, imperturbable and lead calm and idle life. Every day he went to the mass, then he used to read in his room, he wrote prose and rhymes – in general, “what he liked.” Dmitry Vasilyevich always used to pray in the evening. And after prayer before going to bed, when everything around became silent, he walked around the house with a candle: he watched whether the windows and the doors were closed. Then he went to the porch and watched whether the attic, inner porch and larders were locked.

Ekaterina Ivanovna wrote, “Remembrance about grandfather is always connected for me with a kind, comforting feeling, as we remembered him, he was never able to offend anyone and endured everything resignedly.

Next to the remembrance about the holy old man I want to tell about his grandson, i. e. about my brother Dmitry Ivanovich. This is my dear brother, the pride and comfort of our family. My heart is full of gratitude to him for his concern for me and my children at anytime…”

Mitenka, loved by everyone, was born on January, 27th (February, 8th) of 1834. This year was a hard one for the family. Ivan Pavlovich had to retire since he had become almost blind. The family had to live on his small pension. The Mendeleyevs moved from Tobolsk to the village of Aremzyanka, where the glass-work, which was inherited by the brother of Maria Dmitrievna Vasiliy Kornilyev, was situated. Maria Dmitrievna got a letter of attorney to manage it.

Dmitry spent his childhood and early youth in the village, among peasants and mill-hands. The problems of manufacturing and agriculture were constantly discussed at the Mendeleyevs. Mother, Maria Dmitrievna, worked tirelessly. She wrote, “My day starts at six o’clock in the morning with the preparation of dough and pastry for rolls and pies, then with the preparation of meal and at the same time with personal orders for the business. Moreover, I walk to the kitchen table, then to the bureau and during the days of payments – right from the cooking to the accounts.” Ivan Pavlovich worked as long as possible. In such an atmosphere Mitya got a respect to labour, interest to the industrial work and agriculture, which remained in him for the rest of his life.

Mitya learned to read, write and count very early. He grew being a bright child. His sister Ekaterina Kapustina liked to tell about the mother wit of her younger brother like that. When she was already married and lived in Omsk, mother with a 6-year-old Mitya visited them sometimes. While entertaining the child Ekaterina Ivanovna played with him a card game, which had been popular then, “tintere” and “sticks”, where the counting played the main role. Little Mitya always defeated his grown-up sister.

When he was 7 years old, he was already prepared to enter gymnasium together with his elder brother Pavel. Mitya studied at gymnasium without any especial progress, treating bona fide only those subjects, which he liked and which didn’t require intensive work. He liked mathematics, physics and history. He was absolutely indifferent towards the Russian philology and religion. He couldn’t stand foreign languages – German and Latin, and only the threat of remaining in the same form for the second year made him study.

The last years of Mitya Mendeleyev’s studies at gymnasium were saddened by misfortunes. In October of 1847 his father Ivan Pavlovich died, three months later one of his sisters Polina – died. In June of 1848 the glass-work in Aremzyanka, which had been for a while the main source of the family’s subsistence, burned down entirely. Maria Dmitrievna had no choice but to liquidate the farm and to leave the native places forever.

The Mendeleyevs passed winter of the 1849–1850’s in Moscow with the brother of Maria Dmitrievna, and in spring of 1850 they went to Petersburg cherishing hopes that Dmitry would be able to enter one of the academies of the capital. They chose the Main Pedagogical Institute (MPI), where Dmitry’s father had studied. The institute was located in the same building with the University, in the building of the Twelve Collegia. It didn’t enjoy wide popularity because of its specialization, but the education here was of the highest level: the professors of the University and academicians were teaching here.

However, the year 1850 wasn’t for entrance. Mother had to do everything in her power so that her son would have been admitted to the entrance examinations; institute friends of Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleyev, who lived in Petersburg, helped her. At the end of summer of 1850 Mitya Mendeleyev was admitted to the physico-mathematical faculty of the Main Pedagogical Institute as a student “at the state expense”. In autumn of the same year, as if having fulfilled her main mission, Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleyeva died. Before death she willed: “… to insist in labour and not in words and to look for God’s and scientific truth patiently…”

Nadezhda Yakovlevna Kapustina-Gubkina wrote in her notes about the Mendeleyevs that Maria Dmitrievna loved all her children, but most of all the youngest. Before death she blessed her son with the icon of the God-mother, where was the following inscription:

“I’m blessing you, Mitinka. All expectancies of my old age were based on you. I forgive you all your mistakes and beg you to address to God. Be kind, honour God, Tsar, Motherland and don’t forget that you should be responsible for everything at the Trial. Forgive and remember your mother, who had loved you more than anyone.”

Many years later, in 1887, being already a well-known scientist, D. I. Mendeleyev dedicated his work “Research of aqueous solutions according to the specific gravity” to his mother: “This research is dedicated to the memory of my mother by her last-born. She was able to nurture him only by her labour, managing the factorial affairs; she educated with her example, corrected with love and moved from Siberia, spending the last might and means, in order to devote to science.”

Student Mendeleyev didn’t have any unloved subjects. Most of all he was keen on abstract mathematics; he paid a great attention to chemistry and physics. But also he studied zoology, botany, he was interested in the sciences, which were studied at the historico-philosophical faculty, he studied at the laboratory of electrotype. Mendeleyev proved to be a many-sided, extraordinarily capable and originally thinking researcher. Intensive work let him enter quickly the number of the best students of institute. When he was a student in his elder year Dmitry Mendeleyev chose for himself two main directions of research: chemistry and mineralogy.

After having graduated the MPI, Mendeleyev presented his dissertation, which was named “Isomorphism in connection with other relations of crystal form to the composition.” Isomorphism is an identity of crystal form under the difference in the solution. This phenomenon is extraordinarily widespread in the minerals. The work, made under the direction of professor A. A. Voskresensky, was of great importance for the future development of scientific interests of the young scientist. At the end of his life he wrote, “In the Main Pedagogical Institute it was required to write a dissertation on one’s own subject – I have chosen isomorphism because I was interested in the things, which I had discovered by myself… and the subject seemed to me to be important in natural historical sense… The compiling of this dissertation involved me most of all to studying of chemical relations. Thus, it determined many things…”

Studying of isomorphism made Mendeleyev clarify the similarity and distinction between the chemical compounds, and 15 years later – to discovery of the periodical law of chemical elements.

In spring of 1855 D. I. Mendeleyev successfully passed the finals in all subjects. Academician U. F. Frizsche, who was present at the final in chemistry, highly appreciated the Mendeleyev’s knowledge and in his letter to the director of the MPI supported the idea of giving this graduate an opportunity to continue his research. In Frizsche’s opinion, Mendeleyev was to get a place for the future work in one of the university’s cities.

Mendeleyev, however, wasn’t able to take advantage of the opportunity to stay at the institute because of the state of health. Already in 1853, having been ill with consumption, he got to the institute sick quarters. Then the physicians didn’t hope already that he would get well again, but Dmitry Mendeleyev recovered and wrote to the doctor in charge of the case a report with a request to take the next exam.

After having finished his studies, Mendeleyev had been appointed as a teacher of gymnasium in the Crimea. Southern air was healthgiving for him. He was prescribed to go to Simferopol. But Mendeleyev couldn’t start working: there was the Crimean war of the 1853–1856’s, Simferopol was situated close to the battle-ground, and the gymnasium was closed. Dmitry Mendeleyev learned that there was a vacant post of teacher in Odessa.

During winter and spring of 1856 Mendeleyev worked as a chief teacher at the gymnasium attached to the lycee de Richelieu. His teaching was of a lively, original and creative nature. Except teaching according to the curriculum, he planned to write a guide for gymnasia, where, according to him, he planned “to describe gases, liquids, geological materials, minerals, remains of the organic creatures, plants starting with the lower ones and animals starting with the human being as a type, who forms a special class, and to finish with… geography.”

Dmitry Mendeleyev not only took an active part in the work as a teacher of mathematics and physics and later of other natural sciences, but he also continued his research. The work generally named “Specific Volumes” was the logical continuation of studying isomorphism. This work was a many-sided research, which is possible to be considered as a peculiar scientific trilogy, devoted to the pressing questions of chemistry of the middle of the 19th century. The scientist addressed to the deeper study of the substance structure, to the problem of the atom and molecule volume. The work appeared to be not only deserving the presentation as a dissertation for the Master’s degree, but right away it became the foundation of the second dissertation “for the right to deliver lectures.” After having come back to Petersburg from Odessa, the young scientist got an opportunity to stay in the capital and to get the post of professor’s substitute at the University.

In 1859 D. Mendeleyev got a permission for a foreign trip “to improve in the sciences.” He went abroad with a properly worked out original programm of the research. The theoretical idea of the close connection between the physical and chemical characteristics of the substance became its foundation. During this period Mendeleyev especially emphasized the research of the cohesion of the particles. He supposed to study them by measuring the surface tension of the liquids (the phenomenon of capillarity) at the different temperatures.

Dmitry Ivanovich wrote, “Being sent oversea in 1859, I studied only the capillarity, supposing to find there the clue to the solution of many physico-mathematical problems”; “… I intended to determine the interdependence between the particle volume and the cohesion”; “The measure of the solid cohesion, undoubtly, is an attribute more intrinsic than i. e. the boiling-point, and until now we have very few data about it.”

Dmitry Mendeleyev left Petersburg without having any clear idea of a science center of Europe where he was going to work. In a month spent on travelling around different cities, he chose Heidelberg, in the well-known university of which worked R. Bunsen, G. Kirchhoff, E. Erlenmeyer and other prominent scientists.

Having settled down in Heidelberg, Mendeleyev right away decided to establish his own laboratory, since it was impossible to carry out such “delicate experiments as capillary ones” in the laboratory, offered him by R. Bunsen. While starting to work the scientist gave a great consideration to the acquirement of good measuring instruments and their thorough study. While working in Heidelberg, studying the interdependence of the particle volume and the cohesion and studying the capillarity, D. Mendeleyev worked out the system of metrology and created the unique measuring equipment. For instance, he developed a fundamentally new instrument for the determination of the liquid density, which was later named after him, – densimeter of D. I. Mendeleyev.

Concerning the series of works of the 1850–1860’s, connected with the research of liquids, Mendeleyev told about it at the end of his life: “Being partly disappointed, I had absolutely given up this difficult subject, where, however, I was thinking independently. It is evident because I discovered the «absolute boiling-point»”. He succeeded to determine that liquid had turned to steam under a certain temperature, which was called by him the absolute boiling-point.

This discovery is the first important scientific achievement of Mendeleyev. Later, after the works of T. Andrews, another term firmed up in the science – “critical temperature.” However, Mendeleyev’s priority in the ascertainment of this significant phenomenon is nowadays undoubted and generally acknowledged.

Mendeleyev’s works on the subject of capillarity, realized by him in Heidelberg, are the logical continuation of his previous research. After having analyzed the whole of the scientist’s works and plans at the end of the 1850’s, it is possible to say that he longed for constructing the general system of physico-mathematical knowledge. Obviously, as a result of his research of the specific volumes the scientist made sure that knowledge about the atom size and the positional relationship of the particles wasn’t enough for the complete explanation of chemical characteristics of substances. He came to a conclusion that they should be supplemented with the characteristics, which were defining the force of interaction of the particles. Mendeleyev tried to work out the main regulations of a special theoretical discipline – molecular mechanics, which rests upon the three values: weight, volume and the force of interaction of the particles (molecules).

Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleyeva (nee Kornilyeva; 1793–1850), the mother of D. I. Mendeleyev. Unknown painter. Oil painting

Ivan Ivanovich Mendeleyev (1783–1847), the father of D. I. Mendeleyev. Unknown painter. Oil painting

The building of Tobolskaya gymnasium, where D. I. Mendeleyev was studying in 1841-1849

Gymnasium attached to the lycee de Richelieu in Odessa, where D. I. Mendeleyev was teaching in 1855-1856

The attempt to construct the molecular mechanics is very interesting. It is an example of the orientation of the scientist’s works to the significant theoretical generalizations. Though today this idea is only of a historical importance, nevertheless, it describes perfectly the independent approach of the scientist to the solution of the problems of the substance structure. In the middle of the 19th century it hadn’t been generally acknowledged yet and it had been supported only by individual scientists in different countries. The molecular theory started to be generally acknowledged only after the International chemical congress in Carlsruhe in 1860.

Participation in the International chemical congress, which took place on September, 3rd-5th of 1860, became for Mendeleyev one of the most bright events of that year, which influenced greatly upon his choice of scientific interests during the following years. Mendeleyev came to the congress as a member of the delegation of Russian chemists, where were N. N. Zinin, A. P. Borodin, L. P. Shishkov, etc. During the congress’s work Dmitry Mendeleyev got acquainted with many prominent scientists of Europe. Those were J.– B. Dumas, Ch. Wurza and S. Cannizzaro, G. Rosko, etc. He continued communicating with them later.

It is difficult to overestimate the meaning of the International chemical congress in the history of chemistry. There was accepted the common system of atomic weights and were defined the conceptions of the molecule and atom.

As stated above, the scientific conceptions, which had been generally acknowledged at the congress of 1860, appeared in Mendeleyev’s research even before; the fundamentals of the molecular theory, as well as the principles of defining the molecular weight and density, were delivered by him at his lectures.

At the beginning of the 1860’s another important event took place in the life of D. I. Mendeleyev. On April, 29th of 1862 there was a wedding of Dmitry Mendeleyev and Theozva Nikitichna Leshchova, the stepdaughter of Pyotr Petrovich Ershov, the authour of the fairy-tale “Konyok-Gorbunok” (“The gibbous horse”). The wife was six years older than her husband. Their first-born son was Volodya, then daughter Olga was born. But this marriage wasn’t a happy one. Active work of a scientist, his uneasy way of life appeared to be far from the supposed ideal of wife. Interests and characters of this married couple were too different. At the beginning of the 1870’s their relationships started being complicated. Theozva Nikitichna gave her husband absolute freedom under the condition that the official marriage wouldn’t have been annulled.

In spite of the difficult relationships with his wife, D. I. Mendeleyev always behaved towards the family very carefully and responsibly. Especially he loved children, he often said, “Whatever I do and, however, I’m busy, I’m always happy when any of them comes to me.” The only thing, which could interrupt his work, were the children. If he suddenly heard the children’s screaming or crying, right away he rushed to find out what had happened. He used to come running and frightened, screamed loudly and threateningly, but in no circumstances at the child, but at the nunny. The nunny experienced it almost always and the children – never. Dmitry Ivanovich said, “I experienced many things in my life, but I don’t know the better happiness than to see my children next to me.”

His niece Nadezhda Yakovlevna Kapustina-Gubkina remembered that he loved and worried not only about his own children. In Boblovo – the estate purchased by D. I. Mendeleyev in 1865 on an equal footing with his friend N. P. Ilyin – in summer there were having rest several families with their children. The kids were always around the master of the house, they used to walk with him on his household business. It was interesting for them to listen to the stories of Dmitry Ivanovich, to walk with him about the forest, to share with him their joys and sorrows.

N. Y. Kapustina-Gubkina remembered an episode, which had vividly illustrated Dmitry Ivanovich’s delicacy towards the child’s soul, his kindness, “In the morning my elder brother and sister were teaching us in Russian and in French. I perplexed in my translation and my sister was keeping me for a long time under the lesson. Dmitry Ivanovich was passing by the sitting-room, where we were studying, and told my sister casually:

– Why are you exhausting her over the book, Anyuta? Let her walk, she will have time.

Right away I ran away, but after forty years I remember how kind he was towards the child’s soul.”