Читать книгу Doomsday - Warwick Deeping - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеArnold Furze of "Doomsday" had paused for a moment where the Melhurst and Rotherbridge roads join each other at an acute angle and become the road to Carslake, for though his day's work began before dawn and went on after dusk he was one of those men who can spare his soul five minutes. A hundred yards farther up the Carslake road his farm lane emerged north of the bank where the Six Firs grew, and on reaching the lane he left his empty milk-can by the hedge, and climbed up beside the trunk of one of the six old trees. Far above his head their outjutting green tops swayed very gently against the cold blue sky. Rabbits had been nibbling the short grass.

Furze stood there, seeming to look at nothing in particular, as much a part of the country as the trees. The rising sun lay behind him. It sent forth a yellow finger and laid it upon that splodge of chequered colour, those abominable little dwellings that dotted the Sandihurst Estate. There were thirteen of them, strung on each side of the cinder track that Colonel Sykes had had made between his red and white bungalow and the road to Melhurst. They looked just like a collection of big red, white, yellow, green and brown fungi, excrescences, each squatting on its quarter acre or so of land, and surrounded by lesser excrescences that were tool-sheds, chicken-houses, and here and there a little tin-roofed garage. Furze knew every one of the thirteen dwellings, though he had not walked up the cinder road more than six times in his life. He supplied the colony with milk and eggs and cordwood and an occasional load of manure. His bills went in once a month.

"What a collection," he thought.

They were of all shapes and all sizes, and they agreed in nothing but in their flimsy newness. Colonel Sykes' red brick and rough cast bungalow headed the formation like a field officer mounted and leading his company up the hill. Oak Lodge, a mock oak and plaster cottage in the Tudor style, contained the Jamiesons, who manufactured jam up at Carslake. Next to it stood "Green Shutters," the home of the Viners, half brick and half tile and pink as a boiled prawn. Following south came the "Oast," a pathetic improvisation contrived out of a circular steel shelter with an old railway-coach attached to it, the whole painted a bright green, and inhabited by one-eyed ex-lieutenant Harold Coode. In his hurry to recoup himself after his speculation in land, Colonel Sykes had sold the plots without troubling himself about building restrictions. Next to the "Oast" the Perrivales had built themselves "Two Stories" in yellow brick. "The Pill Box," a cement block structure, looking like a white box with four red chimney pots placed on it, belonged to Mr. John Brownlow—a retired schoolmaster. The Engledews lived in the "Lodge," by the Melhurst road. On the west side of the cinder canal the buildings were even more amateurish and ephemeral. Lieut. Peabody had placed two Nissen huts side by side, painted them red, joined the fronts with a white veranda, and christened the creation "Old Bill." The Vachetts—literary people and very desultory at that, inhabited a red and white bungalow, "Riposo." The Clutterbucks had had to be content with a big corrugated iron hut that resembled a football pavilion or a mission hall. Commander Troton owned "The Bungalow," brown stained weather board and pink pantiles. Lieut. Colonel Twist had put up a chalet and called it what it was. The Mullins' had shown a sense of humour in calling their cement box "Pandora," for it was full of children and prams, and rag dolls and trouble.

Furze's very deep blue eyes seemed to question the significance of this colony. He considered it as a native might speculate upon some sudden growth of alien haste, and, as he scrambled down into the lane and picked up his milk can, his thoughts remained with Cinder Town. He saw in it one of those improvisations flung up by the confused flux of the post-war period. The new poor! The relics of a superfluous generation dumped down among Sussex clay. Impoverished gentlefolk drawn together in a little world of makeshifts, and keeping up appearances—of a sort. Rootless people, withering, waiting to die. It was rather pathetic. What on earth did they do with themselves in those little transitory houses on their quarter-acre plots, without a decent tree on the estate, and the very road a squdge of clay and clinker? Keep a few chickens, and grow starved vegetables, and train nasturtiums up flimsy trellises? One or two of them had hired land and were chicken farming. Chicken farming! Lieut. Peabody had planted fruit trees on a south-west slope full in the blue eye of the Sussex wind! And that girl with the smudgy face, and the soft coal-dust eyes who had taken in the milk? Deputizing as a maid of all work? Well, anyway, she worked, did a woman's work, though it might be because she could not help it.

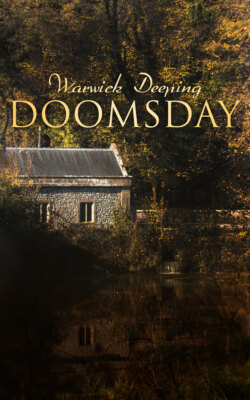

Passing on up the farm lane between high hedges of thorn and ash and maple, with the Ten Acre on his right, and the Ridge Field on his left, Arnold Furze returned to a world that seemed solid and real. He paused—as he often did—just above the pond—to see the greyish brick chimney stack of the farmhouse showing above and through the bare poles of the larch plantation. From this point above the pond where the lane began to dip and the hedges were lower, he could command the greater part of his farm. Immediately below him stretched the pond and the two old ilexes at the end of the larch plantation, and beyond them lay the yard, and the stone farm buildings their grey walls and rust coloured roofs patched with yellow lichen. Rushy Pool and Rushy Wood were hidden by the larches and the house, but above the swelling brownness of the Sea Field, the beeches of Beech Ho seemed to carry the sky on their branches. Eastwards, along the slope of the valley the greenness of the Furze Field met the deeper green of a wood of Scotch Firs. Southwards at the heel of the Gore, and lying in the deep trough of the valley, the oaks of Gore Wood stood embattled at the end of the Long Meadow. The old cedar beyond the orchard raised three dark plumes above the roof of the house, and further still the spruces at the south-east corner of the Doom Paddock would flash like spires in the sunlight.

To Furze it was very beautiful with all its changing contours, its high woods, and the swelling steepness of its grass and arable. Never did it look the same, but was eternally changeful above the green deeps of its valley where the brook ran down to Rushy Pool. Difficult—yes—but he never grudged it its difficulties; for a beauty that is loved is born with in all its moods and mischiefs. For five years now he had been able to call "Doomsday" his. He had fought it, loved it, wrestled with it, and there had been times when it had threatened to tear the guts out of him. But that was life. Better than finnicking about in an office, and putting paper over your shirt cuffs.

He went on and down to the path above the yard. A middle-aged man with very blue eyes and a moustache the colour of honey was forking manure out of the cowhouse.

"Will."

"Sssir—"

"We'll cart that wood up from the Gore. I'll be with you in ten minutes."

The blue-eyed labourer thrust his fork into a pile of smoking dung, and went with long trailing steps towards the stable, turning to glance over his shoulder at Furze who was disappearing behind the yew hedge screening a part of the garden. But there was no garden there now, only coarse grass and a few old unpruned roses. Arnold Furze had no time for life's embroideries.