Читать книгу Doomsday - Warwick Deeping - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

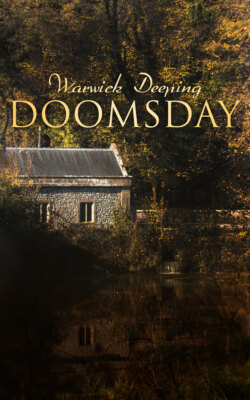

ОглавлениеA part of Doomsday Farmhouse had been built by a Sussex ironmaster in Elizabeth's day, and to this man of iron it owed the stone walls of its lower story, its stone mullions, and its brick chimneys. The second story warmed itself with lichened bricks and tiles. The spread of its red-brown roof with its hips and valleys had an ample tranquillity. The parlour, jutting out queerily towards Mrs. Damans' sunk garden, had a roof of Horsham stone, but Mrs. Damaris had been dead a hundred and seventy years or more, and her sunk garden had become a sunny place where hens clucked in coops and yellow chicks toddled about over the grass. Many of the windows still held their lead lights, but in the living-room and the parlour they had been replaced by wooden casements. As to its setting, nothing could have been more charmingly casual and tangled and unstudied. On the east the branches of the old pear and apple trees of an orchard almost brushed its walls and held blossom or fruit at the very windows. Behind it lay the vegetable garden backed by the larch plantation, and full of lilacs and ancient rambling currant and gooseberry bushes, and groves of raspberry canes, and winter greens, and odd clumps of flowers. The tiled roof of the well-house was a smother of wild clematis and hop. South lay Mrs. Damaris' little sunk garden, its stone walls all mossy, and the four yews—left unclipped for many years—rising like dark green obelisks. Beyond the orchard the big cedar looked almost blue when the fruit blossom was out. West of it, the cow-houses, stable, barn, granary, and waggon sheds were grouped about the byres and rick-yard. The sweet, homely smell of the byres would drift in on the west wind. Everything was old, the oak of the fences, the posts of the waggon sheds, the big black doors of the barn, even the byre rails and the palings of the pig-sties. Silvered and green oak, grey stone, the mottled darkness of old brick and tile. The gates leading into the lane and the Doom Paddock were new, for Arnold Furze had made and hung them on new oak posts. The gates he had found there had been tied up with wire and lengths of rope, and patched with odd pieces of deal.

From the window of the parlour you looked over Mrs. Damaris' little sunk garden and the Doom Paddock to an immense thorn hedge that hid the Long Meadow, and the brook beyond it. Rushy Pool glimmered down yonder towards the rising sun. The high ground on the other side of the brook rose like a green, tree-covered cliff in which were cleft blue vistas of woods and shining hills, and white clouds low down on the horizon by the sea. The sea was fifteen miles away, but when Arnold Furze was hoeing turnips up in the Sea Field he could lean upon his hoe and see the grey hills flicker between him and the old memories of France and the war. The birds in these Sussex woods had heard the rumble of the guns in those days, guns at Ypres, guns on the bloody, white-hilled, red-poppied Somme. Furze had been with the guns, the captain of a 4.5 Howitzer battery. It seemed very long ago.

A year as a learner on a farm in Hampshire, and five years at Doomsday! Five notable, terrible and glorious years, full of sweat and hate and love and weariness, and a back that had refused to break, and a stomach that would digest anything. Lonely? O, yes, in a way, but when a man has beasts and sheep and pigs, and two horses, and a dog, and a cat, and a number of odd hens and ducks to look after, his hands are full of life. And there were the birds, and the crops, and the trees, and the yellow gorse, and the wild flowers, all live things. No, a man had no time to be lonely, with Will Blossom and Will Blossom's boy and himself to work a hundred and twenty acres, though twenty acres of it were woodland. And difficult land at that. Heavy—some of it, and steep.

Five years!

He came up the stone steps to the door, with a great red winter sun setting behind him over the roof of the waggon shed. His boots were all yellow clay, and there were spots of it upon his face. He shaved himself twice a week. Bobbo the sheepdog flummoxed in at his heels, and making for the log fire on the great open hearth under the hood of the chimney, lay down to share it with Furze's black cat. The floor of the living-room was of red tiles, which made it safe for Arnold Furze to keep a wood fire burning and to pile upon it three or four times a day billets of oak and the butts of old posts and the roots of trees. In the winter this fire never went out, for in the morning two or three handfuls of kindling thrown upon the hot heap of wood ash would break into a blaze. He kept his logs and billets in the living-room, a great pile of them stacked in a corner.

Here—too—an iron kettle was usually simmering on the hook. Tea-making was a simple process. The breakfast tea leaves were shaken out of the teapot upon the fire, more tea was added from a canister on the shelf, the kettle seized with an old leather hedging-glove, and the teapot filled. Milk, a loaf, butter on a white plate, and a pot of jam waited in the cupboard beside the fireplace.

Furze had his tea by the fire. He sat on an oak stool of his own making, like some Sussex peasant of the iron days before man had realized cushions and comfort. He too was of iron, one of those lean big tireless men with his strength burning like a steady flame. You saw it in his eyes; it waxed and waned; it might die down like a flame at the end of the day, but with the dawn of the next day it was as bright as ever. He needed it, but he needed it a little less than he had done, for he had his feet well set in the soil, and could draw his breath and look about him.

Before filling his pipe he poured out a saucer of milk for Tibby the black cat. The dog, a devoted and lovable beast, cuddled up beside him like a shaggy second self, his muzzle resting on Furze's knee, while his master sat and smoked, and allowed himself one of those short interludes that were like the five minutes' halt on a long march. The fire flung the shadows of him and his animals about the bare, old room with its brown distempered walls and beamed ceiling. He had a way of holding the stem of his pipe in his left fist as though he could not touch a thing without gripping it.

The fire was good, like all primitive phenomena to a man who is strong, and Furze's life at Doomsday was very primitive, and not unlike a colonist's, a concentration upon the essential soil and its products, an ignoring of individual comfort. He had come to Doomsday with a claw-hammer, a spanner, and a saw, his flea-bag and camp equipment, and a hundred pounds in cash, all the capital that was left him after the purchase of the farm. War gratuity, savings, the thousand pounds an aunt had left him, Doomsday, derelict and lonely, had swallowed them all. A Ford taxi, chartered from Carslake station, had lurched up the lane, and deposited Furze and all his worldly gear on the stone steps of the old, silent house. He had slept on his camp bed, washed in a bucket, used a box as a table, and another box as a seat, camping out in one room of the rambling and empty house.

From that day the struggle had begun. And what a struggle it had been, that of a lone, strong, devoted man who had that strange passion for the soil, and who combined with his strength, intelligence and a love of beauty. There had been hardly a sound gate on the farm; the hedges had been broken and old and straggling into the fields like young coppices. The Furze Hill field had been a waste of gorse; the Wilderness a tangle of brambles, bracken, thorns, broom, ragwort and golden rod, and it was a wilderness still. The coppice wood had not been cut for seven years in either Gore or Rushy Woods; elms had been sending up suckers far out in the Ten Acre; weeds had rioted, charlock and couch and thistles. Dead trees had lain rotting; a beech, blown down in Beech Ho, had never been touched. The stable roof had leaked. The gutters had been plugged, so that water had dribbled down the walls. The byre fences had sagged this way and that; the roof of one of the pigsties had fallen in. Nettles had stood five feet high round the back of the house.

What a first six months he had had of it, working and living like a savage, but a savage with a sensitive modern soul! An occasional stroller along the field path that crossed Bean Acres and Maids Croft and ran along the edge of Furze Hill to Beech Ho had seen him as a brown figure in old army shirt and breeches, swinging axe or mall, or lopping at an overgrown hedge, or cutting over the tangled orchard, or ploughing with his one horse and second-hand wheel plough. Wandering lovers had discovered him scything or hoeing in the dusk; only the birds had seen him in the dawn, with dew upon his boots and a freshness in those deep-set blue eyes. The lovers had marvelled. They had talked about him at Carslake in the shops and the pubs. "Mad Furze"—"Fool Furze"—"Mean Furze." Mean because he had had to set his teeth and calculate before buying anything. He had never missed a sale, and had brought away old harness to be pieced and patched, old tools, a machine or two, just as little as he could do with. All his shopping had been done up at Carslake on Saturday nights, and the tinned food, the jam and the tea and the sugar, and his week's tobacco, and an occasional piece of butcher's meat, had been carried home in an old canvas kit-bag. For a year all the ready money that had come to him had been provided by the milk of two rather indifferent cows and the sale of a couple of litters of pigs. He had eaten the eggs laid by his dozen hens, and helped himself to live by the few vegetables he had had time to grow. So grim had been the struggle that he had had to sell some of his timber, fifty oaks in Gore Wood, and it had hurt him.

He stared at the fire and stroked Bobbo's head.

My God—how tired he had been sometimes, ragingly tired. He could remember hating the place for one whole winter month with a furious and evil hatred. It had had its claws in his soul's belly, twisting his guts. Beaten—no—by God! He had trampled on in his muddy boots, without time to cook or wash, sleeping like a log in the flea-bag on his camp bed. Lonely? Well, he supposed that he had not had time to feel lonely. Holidays? Perhaps seven days off in three years.

Half playfully Furze blew smoke at the dog—and stretched himself on his box in front of the fire. He had made his roots; they were not as stout as he intended them to be, but they were there. Twenty good shorthorns, thirty sheep, two horses—fine dapple greys—six black pigs, fifty or so fowls, and a dozen ducks. And manure stacking up, and Rushy Bottom, the Long Meadow, Doom Paddock, and the Gore growing good grass with clover in it, and his winter wheat showing well in the Ridge Field, and a hundred-ton crop of mangels clamped, enough for all his stock. He had had a bumper hay crop. He had a man and a boy now to help. This spring he would be able to buy a new mower, and a new horse cultivator, and in the autumn perhaps a corn crusher, a decent tumbril.

He knocked out his pipe on the toe of his boot.

"Come on, Bobbo. Work."

He lit a lantern, and as he went down the steps and along the path with the shadows swinging from the light, he heard the chug-chug of a chaff cutter. A good sound that. He sniffed the sweet smell of the byres, and looked up at the stars.

A minute later he was in the big cowshed, helping Will with the sliced roots and the hay. The place steamed; it was full of the sweet breath of the beasts and the sound of their breathing and feeding. Rows of gentle heads and liquid eyes showed in the long, dimly lit building, and the warm, milky, bestrawed life of it sent a whimper of pleasure and of pride through Furze's blood. He was fond of his beasts, and as he passed down the building, his hand caressed the placid creatures—"Well, Mary—well, Doll—old lady." The dog kept close to his heels, and the cows, accustomed to Bobbo being there at feeding time, were not troubled by his nearness.

Will Blossom, with a dusting of chaff on his honey-coloured moustache, went through the cow house, holding his lantern shoulder high.

"That thur wood be ready loaded f'tomorrer, sir."

"Right, Will. Good night."

"Good night, ssir."

Blossom went out with his lantern, but Arnold Furze remained for a while in the cow house, watching the cows feeding, and feeling the warm contentment of the big brown creatures.