Читать книгу The Anatomy of Harpo Marx - Wayne Koestenbaum - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Holy Fool Flees Language’s Stink Bomb

THE COCOANUTS (1929)

He was attached to sounds and because of his attachment could not let sounds be just sounds. He needed to attach himself to the emptiness, to the silence. — JOHN CAGE, Silence

I

ENTRANCE At the studios of Paramount Pictures in Astoria, Long Island, in his first scene, his first major film, 1929, six years before the Third Reich passed the Nuremberg Laws, Harpo enters honking. Honk honk. Pause. Honk honk. Lemming-like, he pursues a woman who doesn’t realize that a kook is shadowing her. What does Harpo want? He wants to honk, copy, play, irritate, smash, point, lean, and rest. He wants to find a double, to be useless, to recognize, and to be recognized. He wants to greet the void. He wants to go blank. Or maybe he wants nothing.

PILLOW BOOKS Originally I intended to write a book about Harpo’s relation to history and literature. A tiny chapter on Harpo and Hegel. A tiny chapter on Harpo and Marx. A tiny chapter on Harpo and Stein. A tiny chapter on Harpo and Hitler.

Then I drafted a novella, The Pillow Book of Harpo Marx. The narrator, Harpo, was a queer Jewish masseur who lived in Variety Springs, New York, and whose grandparents had starred in vaudeville with Sophie Tucker.

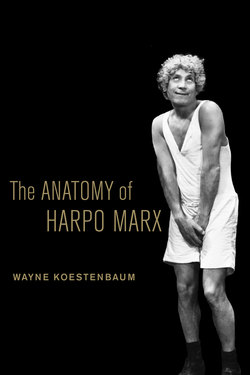

Then I decided I didn’t want to waste Harpo’s name on a novella. So I set out to write the book you are now holding—a blow-by-blow annotation of Harpo’s onscreen actions. My aim? Assemblage. Homage. Imitation. Transcription. Dilation.

Last night I dreamt that my typewriter’s ribbon expatriated from the machine and curled onto the floor. Dreams are evidence I can’t omit from my pillow book.

This opening chapter has the fewest pictures. At first I didn’t realize how pleasurable it was to interrupt the movie and seize proof that Harpo was god-like, exemplary, in danger of vanishing if I didn’t capture him. I won’t go back now and resee The Cocoanuts and grab more pictures; I won’t doctor my experimental anatomization of Harpo’s anti-melancholy body, whose materiality suffuses me with physical contentment, as if I were rocking the infant universe to sleep. When I first fell in love with Harpo, it wasn’t, however, his contentment that struck me; I was moved by his hyperkinesis. Other actors handled plot doldrums, while, in the corner, Harpo, unregarded, unspeaking, busied himself with rapid oscillations of head, eye, and hand, self-pleasuring vibrations that sometimes struck sparks in other players, though, mostly, Harpo’s butterfly gyrations woke no one else to his centrality. I, as viewer, was responsible for granting him primacy; and I could do so only by slowing him down and giving words to these muscular mutations, these gestures of mouth-opening and wrist-bending that were, on the surface, merely funny but, below the surface, were uncannily empty. The idiosyncrasy—Harpo’s nod, or cavern-mouth, or mica-eyes—appeared fleeting and subverbal; and I developed a need to convince strangers that Harpo’s hyperkinetic emptiness had metaphysical dimensions.

CONCENTRATION, ABSTRACTION, SERIALITY Harpo is the silent brother. Could he really talk? Yes, but never onscreen. Later, I’ll explain why.

The Marx Brothers had a stage career (vaudeville, Broadway) before their act immigrated to Hollywood; I will limit my attentions to Harpo’s film embodiment.

Watching his screen adventures, I don’t laugh; I concentrate. Concentration is a sadly dwindling cultural resource; opportunities to pay attention— even going overboard and fastening monomaniacally to a single object— deserve advocacy.

Art, whether visual or literary, may choose to operate in serial fashion, composing its tricks by lining up similarly timed or similarly spaced modules. In Harpo’s performances, one gag, or incremental piece of comic business, follows another. His gestures obey a mysterious nonlogic of mere adjacency. The schtick’s fragments stack up like cubes or buttons—impropriety’s rosary-beads. His performances, like the ocean’s, are abstract. We observe the ebb, but we don’t expect an explanation.

Behaving as a serial artist, Harpo lines up his self’s pieces, one by one, in a row: he gathers comic bits into a transparent assemblage, hieratic as Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, but without didactic baggage. The seeming continuity of Harpo’s performances disguises their origin in separable flashes of comic perception. Walter Benjamin described the art of Charlie Chaplin in similar terms: “Each single movement he makes is composed of a succession of staccato bits of movement.” In a different context, the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, attuned to pieces, theorized an ego’s tendency to be “in bits.”

Sequentially, bit by bit, this book will point to Harpo’s screen gestures. My procedure courts overthoroughness, and therefore stupefaction—an interminability I consider Novocain. As Andy Warhol filmed a man sleeping, and called it Sleep, I want to commit media-heist, to steal a man from his native silence and transplant him into words, if only for the pleasure of taking illusory possession of a physical self-sureness that can never be mine.

The Marx Brothers were not part of my star-infatuated childhood; I fell in love with Harpo only recently. Without foreknowledge, I found myself hypnotized by the curly-wigged man who stared erratically, with a glazed expression, in a direction that was neither toward nor away from the other; his gaze seemed to evade reciprocity, yet also to invite response. Harpo, I discovered, moved more quickly, and more elusively, than I could account for. If I slowed down the film, his gestures could unfold under a different planetary dispensation. I wanted to figure out how he put together “cuteness” from scratch, and how he coined, with tools of no one else’s devising, a grammar of adorability, affection, stupefaction, giddiness, sleepiness, shock, and other category-defying moods. I wanted, above all, to figure out how he seduced me into relinquishing my own thoughts, for a few years, to concentrate, instead, on his gestures, which didn’t need my annotations. Harpo made thirteen films; because my goal is homage and replication, I’ve written thirteen chapters. Anatomizing rather than synthesizing, I bed down with entropy and disarray.

FAMILY CHARACTERISTICS The Marx Brothers film career officially begins with The Cocoanuts (1929). I take 1929 personally: my mother was born in 1930, my father in 1928. Though my father is certainly a talker, and a master of esoteric words and abstract concepts, in my childhood he was often silent—either sulking, or bitter, or contemplative, or outshouted. I interpreted his silence as a comforting antidote to my mother’s explosiveness, although now I can conceive that her liveliness and candor offered a different kind of comfort, a tactile realm of figuration, a warm materiality, apart from the bodiless void of my father’s abstraction. But when I was growing up, I felt sad that my mother didn’t decode or translate my father’s muteness, and I idealized (and blamed myself for) his gloom, passivity, or nonreactivity, as if we four children had conspired to deprive him of speech.

In Harpo’s first scene, I glimpse his major gimmicks. I note his rouged lips; his thirst; his appetite; his laziness; his musicality; his whistling; his marveling relation to words as material objects; his plug hat’s height and élan; his pants, not as ragged or droopy as in later films; his belt, not connected to the function of upholding pants; his gaze, riveted to any passing woman; his bulbous taxi horn, phallically protruding, and providing protest or emphasis; his willingness to fight against women rather than merely to romance them; his cheerful distaste for regular channels of communication; his large eyes, rapt, like a painter’s or bird-watcher’s, seizing transitory visitations. Harpo’s eyes are bigger than a regular person’s. That is an anatomical fact I can’t prove. His eyes, which tend to brighten and pop, dramatize the attempt to recognize (or to seek recognition from) another person. Harpo’s bug eyes do more than beseech: they attest, grip, sign, declare, accuse, renounce, and mourn.

DEADNESS I offer verbal attunement to a dead man—a man already “dead” (or abstracted) when alive. We consider his stupefaction funny. By misinterpreting deadness, we wound him; we misread his incapacity as a joke, and we admire his fanatically precise reassembly of woundedness into action.

Bullied, Harpo fled school during second grade and never returned. His onscreen silence rebukes an America that refused him an education. Shouldn’t a New York City truant officer have knocked on his family’s door, 179 East 93rd Street, and demanded that little Arthur—pronounced “Ahtha”—go back to school? In his act’s staccato periodicity, I hear a percussive, repeated complaint, unspecified in content and in addressee. He is rebuking himself for failing to speak, rebuking others for speaking, and rebuking the social contract for ignoring his existence. Watching, we, too, become wounded. Stars mar us; we receive vicarious illumination, but they outshine and therefore humiliate us by reminding us of our nugatory status as nonparticipants in screen existence. Let’s revise the public discourse that considers us vultures, feeding on celebrity carrion; stars damage us by colonizing our consciousness and by persuading us that being cinema-worthy is the only way to shine. I will concentrate on moments when Harpo’s eyes shine, as if they were trying to articulate a desire on the threshold of awareness.

BIRTH ORDER Harpo is the second brother. (So am I.) Actually, Harpo is the third brother. The very first Marx child, Manfred, died as an infant. (I, too, am the third child: my oldest sibling was stillborn.)

After Manfred came Leonard, a.k.a. Chico, in 1887. Chico is the wheeler-and-dealer, the charming gambler and schemer, the dolt with a stereotypical Italian accent.

In 1888, Adolph was born. He later changed his name to Arthur. We know him, however, as Harpo, the silent one.

In 1890, Minnie Marx gave birth to Julius Henry, who grew into Groucho. Loudmouth with a cigar and painted mustache, he is the most educated of the brothers, and the most celebrated. Deposing Groucho from vocal sovereignty might have been Harpo’s covert aim.

The youngest child, Herbert, born in 1901, ended up as Zeppo, the conventionally handsome, matinee-idol brother, the straight man, the only plausible love-interest.

I’ll ignore the second-to-youngest, Gummo, who doesn’t appear in films.

I have two brothers, one sister. Maybe one day I’ll write about sisters. But my subject here is brothers, or the sensation of losing identity amid fraternal haze.

DUCK-MOUTH Harpo, in his first scene, juts out his lips to compose an indignant chute, like a piggybank slot, or a vacuum-cleaner attachment: I call this mannerism duck-mouth, or chute-mouth. I will often mention it—because it attracts me, and because it confuses me, and because its repetition (again and again the duck-mouth) might have comforted him. He doesn’t want to be a duck, but he seems to realize that duck-mouth brings results. Harpo is a pragmatist, though the fruits of his actions are often ephemeral—trifles like satisfaction, attention, recognition, surfeit, stasis, excess, magnification.

As soon as Chico says, “We sent you a telegram,” Harpo faces forward, greeting the Broadway audience, the camera, or some offscreen presence. Seismic processes—gravity, time, sequence—transpire without intervention; we needn’t manually turn causality’s wheel. Harpo proposes liberation from the need to push reality into prescriptive, fixed formations.

CONSUMING THE INEDIBLE Harpo sits on the couch. Beside him, at attention, gazing upward to the ceiling, and not looking at Harpo, stands a hotel porter in white tux jacket. Harpo removes one of its silver buttons, holds it at a distance to identify its nature, polishes it, and pops it in his mouth. He turns toward the camera, smiles, and nods: tastes good. The experiment succeeded. Eating a button, he violates dietary laws, and ingests the forbidden, the inedible: Judaism calls it “treif.” Harpo plucks another button, chews it, and wipes his mouth with the stooge’s bow-tie. Sacrilege intensifies: loafing on the couch, Harpo rests an ankle in the lackey’s hand. The poor guy, demoted to furniture, ignores the insult and stands stiffly at attention, forced to obey a fool.

Groucho calls Harpo a “groundhog.” Button-eating has turned him into an animal, an escapee from a Kafka story. Becoming an animal (or, as theorists Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari put it, becoming-animal) is a laudable human tendency. Harpo may, in fact, represent a semi-utopian condition of permanent ascent into animality, a variety of exalted consciousness.

All this talk of “exaltation” shouldn’t make you forget that my topic is a dead man. I began writing about Harpo in the months after the death of my favorite singer, the soprano Anna Moffo, who is famous for having a voice of unusual voluptuousness and lightness, and also famous for having lost that voice prematurely. She died on March 10, 2006. The word anatomy, in the title, accidentally refigures her name: Anatomy is “Anna to Me.”

HARPO’S EMPTINESS Emptying myself, I try to become as erased and vigilant as Harpo, who, sitting on the couch while Chico and Groucho talk, maintains a spy’s posture, eyes attuned to ambient frequencies. The porter tries to take Harpo’s suitcase. Harpo, thinking himself robbed, fights back. In the scuffle, the suitcase opens and proves to be empty, like Harpo’s wordless mind. His blankness lacks presuppositions and forbids reciprocation. If you don’t interfere with Harpo, and you satisfy his oral needs (give him coat buttons to chew, and ink to drink), he will be a glad groundhog; but if you thwart him, he will bop you over the head with his honker, a subaltern’s scepter, providing a merely playpen sovereignty.

The title’s “cocoanuts” refers to the Marx Brothers, whose Jewish “nuts,” their testicles, their masculinities, have a suspect, pigmented, tropical undertone; but the fruity title especially applies to Harpo, a sweet nothing with a hollow noggin that promises a forbidden medley of milk and meat.

EXCOMMUNICATION: THE THIRD LETTER Harpo, baby monster, sits on the desk and methodically tears up mail. Excommunication delights him. Advocating witless increase, magnification for magnification’s sake, Harpo is overjoyed to repeat the same action: reach into the mail cubicle, retrieve a letter, rip it up, remove another letter, rip it up. His eyes flash as he probes the postal beehive; his other, unoccupied hand hangs suspended, conducting a phantom orchestra. Enthralling, the speed and efficiency of Harpo’s reverse factory, an assembly line that destroys rather than produces. His gaze pivots between letters and Groucho, to whom the mail-destroying feat is a potlatch obediently offered.

When a hotel employee hands Groucho a telegram (actually, a bill), Harpo intercepts and shreds it. Harpo, bookkeeper, performs his favorite function, erasure, canceling debt in medias res. If asked to perform a three-part task, he skips the middle step. If ordered to deliver a message, he destroys it.

Comedy’s rhythm: do anything, however trivial, three times. Make a motion; repeat it; repeat it again. Harpo’s eyes flash when he tears the third letter. The first two gestures are exploratory. With the third letter, he moves from experiment to ecstasy. Like an anteater examining its prey, or like an absorbed infant contemplating a rattle, Harpo glances at the letter-about-to-be-delivered. By ripping it up, he reenacts the destruction of his own voice. Toward his voicelessness—as toward the letters he aggressively destroys— he exhibits no pity, no chagrin. We might consider language’s disappearance a nightmare, but Harpo finds it Lethean.

RATIOCINATION IS FUNNY Harpo sees what resembles a potato but is actually a sponge; he prongs it with a pen, as if with a fork, and chews experimentally, slowly, quizzically. (We can see him think. For our sake, he exaggerates ratiocination, and turns it into a joke.) With Butoh-precise gestures, he spreads paste on the sponge and drinks the ink from the jar, a mock-teacup. Fussy Harpo examines a bouquet before choosing the ideal blossom to eat, and almost “cracks up” at his own preposterousness.

THE INSTANT OF EYE CONTACT WITH THE VIEWER Note Harpo’s distended, glowing, mesmerized eyes, peering, out their corners, toward the camera. His gaze, no longer shy about confronting us, implies: I know that you see my misbehavior. I like being caught. Harpo recognizes the viewer recognizing him. After bliss, an attack of autohypnosis seizes him and shuts down pleasure; glazed eyes, turning away from the camera, sever our momentary bond.

HARPO WANTS MORE OF THE SAME Harpo defines appetite eccentrically. Give me more of the same. Let me keep biting. Aesthetic process—creating and receiving—also obeys this accretive motion.

When the phone rings, Chico answers it, and Harpo makes musical mischief by ink-stamping any available surface: each time the stamp concussively strikes, it produces a different pitch. Sometimes he hits the bell’s bull’s-eye, inadvertently calling a hotel maid: “Did you ring, sir?” she says, saluting, and then, with each accidental ring, another girl appears. Seeing the first maid arrests Harpo: he has discovered a magic switch but doesn’t understand the cause-effect relation between bell and Being. And thus Harpo is entitled to live in the entranced gap between cause and effect, off samsara’s wheel.

WAVING GOOD-BYE TO SOMEONE WHO CAN NO LONGER SEE YOU Harpo doesn’t mind being rejected. He waves good-bye to the girls, already out of sight. A Harpo trademark: waving to someone who can no longer see you. He acts chummy with the void. His wave dignifies the useless communication, the for-nothing. Demonstrating a pointless, antiutilitarian beauty, he puts effort and artistry into a motion unseen by companions. Thus Harpo, an autoerotic autocrat, denies that affectionate actions need recipients.

KINESIS PRECEDES THINKING Move, then think. Act, then contemplate. Obey the body’s innate intelligence, its wish to move. Writing is kinetic. These sentences obey my movement-based desire to concentrate on a vanished subject.

Chico and Harpo take turns spinning around a crook—played by Cyril Ring, who also appeared in Bette Davis’s Mr. Skeffington and Barbara Stanwyck’s The Lady Eve and Judy Garland’s Babes in Arms. (Hollywood intertextuality is important: kabbalah-like, it confirms cinematic kismet.) Men aren’t supposed to dance together, but Harpo’s kinetic momentum prevents the comrade from understanding the act’s compromising nature.

Let me be clear. I’m not saying that Arthur Marx—the real Harpo—was queer. I’m not saying anything about the sexuality of the real Arthur Marx. How could I? (Oh, I could say a few things: he was happily married to actress Susan Fleming. They wed in 1936, when Harpo was forty-six years old. His closest friend was the theater critic and Algonquin Round Table wit Alexander Woollcott, who happened to be queer, and who happened to be, as Groucho put it, “in love with Harpo in a nice way”—a relationship about which there has been a certain amount of intriguing though ungrounded speculation.) Nor am I saying anything about what Harpo, the character, wants. “Harpo,” onscreen, is a fiction. And fictions don’t have desires. They have actions. Harpo’s actions I choose to take queerly. Don’t accuse me of outing anybody! I’ve never outed anyone in my life. I’m simply watching Harpo dance with a man.

TURN A SHAME WORD (BUM) INTO A REPEATABLE MUSICAL OBJECT Cyril—bully, snob, Gentile—calls Harpo a bum. “Come, Penelope, let’s get away from this . . . bum.” Tramp. Rear end. The word bum, though it stuns and shames, provides ammunition. Here is a word that Harpo can handle—a juicy, containable morpheme, an almost onomatopoeic syllable, whose low, corporeal sound reinforces its sense. Again he mouths the word: “bum.” It may mean nothing to him, but it offers a pretext for testing out repetition, for moving his lips, for enunciating. Bum—insult—turns into kernel of song. Harpo mouths the word to Chico, who provides sound. And as bum repeats—“bum, bum, bum”—it accretes into a rhythm, an abstract pattern. Chico sings and Harpo mimes “bum-bum-bum” while exiting, Harpo holding a phantom flute and audibly whistling. (Words may be out of bounds, but nonverbal noises are kosher.)

I’VE ACCOMPLISHED ANOTHER TRANSFORMATION Pleasure, for Harpo, lies in transformation for transformation’s sake. Why not be thrifty, and make use of every inanimate scrap? (Gertrude Stein’s credo: Use everything.) Harpo takes part in the grand tradition of art (from Marcel Duchamp to John Cage to Dieter Roth, and beyond) that recycles—or transubstantiates—debris.

At the hotel’s registration desk, Harpo sniffs the telephone, scrutinizes it, tries to interpret it, to cozy up to it, as if it were human. Then he chews the phone and looks toward the camera; his eyes, alight with pleasure, signify it tastes good or else I’ve accomplished another transformation; I’ve metamorphosed phone into food. The ink jar, like a precious thurible, glistens; pinkie in air, he drinks. Harpo’s face, a scientist’s, evaluates. With a receptivity to the strangeness of the ordinary as radical as Thoreau’s or Wittgenstein’s, Harpo treats existence as a sequence of experiments, none fatal. He puts down the ink jar, smiles, and nods. Job well done, another foodstuff pilfered, another item of garbage transformed into treasure.

When Chico enters, Harpo’s face remains immobile—arrested by panic—but his alert eyes try to figure out whether the universe is sanely functioning. Hyperawareness of atmospheric dangers is an opportunist’s, a paranoid’s, or a traumatized soul’s—a shtetl mentality, transmuted to Paramount.

THE SWITCH TRICK One of Harpo’s trademarks is the “switch trick”—instead of giving his hand to someone who wants to shake it, Harpo offers a leg. The detective unconsciously grasps the leg and then angrily thrusts it away when he realizes the ruse. This trick always satisfies Harpo. It gives him a chance to rest his leg. It eroticizes the handshake’s masculine formality. It amplifies the offering. It confuses the enemy. It stuns—stops—time. It stymies the equivalence, the fake parity, of hand and hand. It interrupts grammar.

Everyone accepts Harpo’s thigh, because the switch trick happens quickly and unexpectedly, and because it lacks apparent logic. Why protect yourself against a nonsense assault? The switch trick blends aggression and intimacy, and proposes substitution as an aesthetic category. Notice the pleasure that hits when one thing replaces another. You expect a fist. You receive, instead, a flower.

THROWING A GOOKIE The detective (played by Basil Ruysdael, a basso who sang in Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète with Enrico Caruso at the Metropolitan Opera) recognizes Harpo’s face, and flashes a “wanted criminal” photo. Reciprocating, Harpo throws him a Gookie. In his autobiography, Harpo Speaks, he calls this trademark expression “throwing a Gookie”: crossed eyes, bloated cheeks, protruding tongue. The gesture originated in cruelty. Mr. Gehrke, in Harpo’s childhood, was an ordinary man who rolled cigars in a store window. Imitating Mr. Gehrke’s expression of rapt, foolish absorption in a task, Harpo stood in front of the window and yelled, “Gookie!”—the Yorkville pronunciation of “Gehrke.” Onstage, the Gookie was a crowd-pleaser. With this trick, he could stimulate a restless vaudeville audience. Onscreen, the Gookie safeguards Harpo’s identity by making him monstrous. Gookie rhymes with two other treats: cookie and nookie. Harpo flashes a Gookie to freeze the villain, as the Medusa’s head turned the viewer to stone. The Gookie, snake-haired, recapitulates the excited stiffness of the penis it wants to embody, or to avoid, or to cut off. (So said Freud—controversially, charismatically.) The Gookie has an affinity with castration, but I can’t make the connection foolproof.

HARPO ACTS EASILY OFFENDED Harpo playfully fingers Chico’s knish-like face. Chico slaps away the exploring hand— leave me alone! Offended, Harpo gives duck-mouth, pushes Chico, and wheels fists into the fight position. (Twice, at the moment a slug is expected, Harpo surprises by kicking Chico’s rear.) Not genuinely angry, Harpo enjoys stepping onto the assembly line of taking offense, a comprehensible sequence: he protrudes lips, kicks Chico, greases comedy’s wheels, advances to the next bit of business, and defends his own chivalric honor. His formulaic set piece—being offended— offers the comfort of imitable units, a Parcheesi pleasure, like Alhambra mosaics or Donald Judd shelves.

BABY-ROMANCING THE LAW: THE NOD Basil the basso-detective intervenes again, breaking up the fight. Now Harpo baby-romances the law by leaning; collapsing, Harpo pushes the horn into the law’s gut, and thereby honks. Harpo has forced the law to operate the farting noisemaker. The honker glues the guys together: they slow-dance. Harpo satisfies a wish to cuddle by turning punishment into cozy roundelay.

The basso-detective says, “I’m going to keep watching”—and Harpo, looking him directly in the eye, nods. Whether or not Harpo agrees, he nods. Reflex actions, mimicking compliance, protect him from the law: you can’t arrest or abuse a nodding man. Let’s take Harpo as emblem of flight from punishment and categorization, including the categories I impose on him.

Harpo steals the basso’s blazer and puts it on Chico. Harpo steals to please his family. Like Oliver Twist under Fagin’s charge, Harpo presents theft’s gleaning to an underworld boss—not to garner acclaim, but to remain securely in the position of tolerated little brother. Brotherliness has a queer energy that Walt Whitman called “adhesiveness”: the democratic desire to attach.

IMMUNITY TO COQUETRY Harpo may chase women, but he foils their advances: heterosexuality, for Harpo, doesn’t compute. And yet Kay Francis, the film’s vamp (soon she’ll star in George Cukor’s Girls about Town and Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise), tries to snare Harpo’s libido. They seem an unlikely match: she’s tall and not Jewish. Flirtatiously, she drops a handkerchief, but he mistakes love-gift for plunder, which he pockets. “Did you see a handkerchief?” she asks. He shakes his head “no” and mimics coquetry by acting femme, while his teeth extract a scarf from her bodice. Earlier, he played this trick on the detective, but Kay’s hankie is longer than the Law’s, and comes from a more intimate hiding place. Harpo mocks private property, puts his mouth to improper use, and interrupts other people’s insincerity. His mouth considers Kay’s hankie an abstract prize, which he hides in his pocket, an almost anatomical safe-deposit box.

WHY HARPO LOOKS DIRECTLY AT THE CAMERA Later, he will learn not to look at the camera. But now, in this primal film, he commits the sin of acknowledging our presence. Mincing, hand on hip, like Mae West, he looks directly at us. His lapse allows me to argue: Harpo, expressing a naked need-for-audience, smashes the diegesis (the technical word for everything that takes place within a film’s fictional world). And by smashing the diegesis, Harpo carves a covert for reverie and for threshold experiences beyond conventional moral accounting systems, including regimes that divide useful and useless acts, and regimes that compel us to choose sociability over introspection.

His horn, colliding with the shutting elevator door, squawks, and he steps backward, arrested, unsmiling, slack-faced. He has failed to prime his features with a signifying expression. Blankness propels him toward music-making; going blank, he relinquishes interaction. Harpo may wish to attach himself to others—especially brothers—but because he lacks speech, he will only thrive when solitary. His contemplative episodes seem like locales rather than merely moods. Consider Harpo a homesteader. Not necessarily a Zionist. (However, at his death, he bequeathed his harp to Israel. I assume that Israel accepted the gift.) Onscreen, he seems a man concerned with escape and territory; his musical solos represent benign, nonviolent flight from the demands of the Other. Harpo, despite clannish chumminess, thrives when abandoned, and when he interacts with his instrument. When I was young, I loved Charlie Chaplin because, clumsy and pallid, he invited us to watch him sulk. Harpo never sulks, and rarely feels sorry for himself, and yet he leans toward emptiness, as if hunting for an echo.

II

HARP AS HOMELAND Seriousness descends. (A rule of Harpo Existence: you can’t make music while kidding around.) Stranded, he has no companion, only a clarinet: he can shove no one else’s body into his transformation factory. He empties himself of alacrity; he needs to purge himself before he dares to perform. His grave face illustrates the pleasure of evacuated meaning. When he plays clarinet, his right cheek expands, but not the left: asymmetrical sign of effortful, onanistic pathos.

Clarinet is just a warm-up; his real instrument is the harp. His harp adventures never change, though their meanings deepen with reiteration: repetition allows us to discover what was immanent in an experience the first go-round. How can we understand Harpo’s harp playing, unless we visit every instance?

In this inaugural experiment, Harpo prepares for solo by posing as bogeyman—looking at the viewer through harp strings, and making a scary face, Hollywood’s idea of a savage. Change of mood: serious, he sits down at the harp, an instrument not meant for men. Harpo’s seriousness butches up the suspect effort. Digital aplomb confirms sexual expertise: this guy knows how to use his fingers. Comedy dies: nap time begins. We can turn away from interaction, moneymaking, cadging, aggression, and garrulity; we can focus, instead, on Harpo’s lushly arpeggiated “soul”—the realm of Jewish feeling, Harpo’s version of singing the blues, a wail with a historical core. The solo’s spiritually assiduous style, a Covenant, is cut off from hijinks. The Marx Brothers never rest; arrivistes, they gate-crash other people’s estates and institutions. Only Harpo’s harp episodes broach the question of homeland. Finally, he gives up hectic transit and failed encounter; finally, he pursues an unbroken, self-generated line of thought.

A medium shot narrows to a close-up, framing Harpo’s face; the viewer presumably wants to spy on Harpo’s private musings, his necromancy—a spell aimed at himself, not at others. Like Garbo, Harpo at his harp is starry, alienated, commodifiable, contained, worth studying and collecting. We see Harpo’s nose in profile. We see how a Jew behaves in secret—an Orpheus with an overlarge, stolen lyre. Harpo, the Jewish fool, plays the instrument that signified, for the British romantic poets, and for anyone influenced by them, the strings of the imagination. In Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Eolian Harp,” nature is a harp, waiting to be plucked by the “intellectual breeze.” Harpo has a lot of responsibility: the fate of Western lyricism rests in his capable, gummy hands.

“WHY BOTHER?” Harpo goes down on all fours, like a baby or a dog, and crawls under Kay’s bed. He loves nooks. He can play marauder without posing a sexual threat. He also possesses the virtue of being empty. He escapes sexual grids; he likes sequestration (pockets, hideaways); he tends toward the animalistic and the puerile; and he prefers to rid actions and objects of their meanings, rather than pile up new meanings.

Leaving his under-the-bed hiding place, Harpo swims like a seal, a watery jet squirting out his mouth: arms make undinal motions, and he wiggles across the floor. Toward humankind he says, “Why bother?” He becomes animal not merely to transgress but to unwind.

JACK-IN-THE-BOX: SUDDEN MANIFESTATION Harpo knocks and enters Margaret Dumont’s room. Margaret Dumont—where do I begin?—is the dowager, the goalpost, the butt of jokes, the consoling maternal presence, the pillar, the wailing wall, the frame, the woman with kind eyes and haughty voice, the woman who bars the brothers from high society but also ushers them into it. Toward Margaret, the cure-all and guardian, the ripe-toned enunciator with a heart of schmaltz, Harpo carries a pitcher of ice water: erotic indifference? Margaret tells him to put the pitcher on the bureau. Instead, Harpo goes to her bed, lies down, and pats the mattress as invitation. When she indignantly refuses, he waves good-bye and exits.

Knock knock. Margaret says, “Come in.” It’s Harpo again—programmed, with a mechanical, tick-tock rhythm, to pop into framed spaces. But then, discovering his mistake (wrong room!), he flees.

Harpo, jack-in-the-box, enacts a rhythm of sudden emergence: I’m-here, quickly followed by I’m-not-here. Harpo is happiest when he first appears. Soon afterward, identity falls prey to dilution. The blitzkrieg instant of arrival finds him most “Harpo.”

GROUCHO’S THIRD-PERSON REFERENCES TO HARPO Groucho says that he doesn’t want to see that “red-headed fellow” running around the lobby. (The film is black-and-white; we’ll take Harpo’s hair color on faith.) Groucho, rarely speaking to him, refers to him in the third person, and holds him within the pincers of adjectives and pejoratives. Later I will describe this effect as the “coziness of interpellation.” It is cozy to be invoked (“that red-headed fellow”) by your brother, even if the reference is negative. It is cozy to be named, and thus summoned into existence.

PLEASURE OF THE INSTANT BEFORE CATEGORIES CLICK INTO PLACE Harpo has little sense of good or evil; freedom from categories accords him cognitive cleanliness. When he does a good deed—he retrieves Margaret Dumont’s stolen necklace—he tampers with the action’s merit by playing a dirty little game; for the pleasure of desecrating someone else’s desired object, he wraps the necklace around his waist and wiggles in a womanly Watusi dance. Ignoring the impropriety, Margaret rewards him with a promotion: “You dear man,” she says. Man?

When questioned by Basil-the-basso-detective, Harpo smiles, oblivious to cross-examination, happy to earn anyone’s attention, savoring the threshold instant of surcease from cruelty, before dread categories click into place, before he understands that the law considers him garbage.

BITING THE FINGER Harpo’s mouth: I can’t get enough of it. Nor could he. Though wordless, he put it to good use. He opens it wide, whenever he gets the chance. He bites the detective’s pointing finger, and won’t let go. Shirking blame for the bite, Harpo gives duck-mouth, imitating normal people’s blah-blah-blah, their chattering doxa.

As a child, I gave vent to rage by biting my right hand’s second finger—the fat place below the knuckle. The gnawed spot developed a callus I feared would cause cancer.

THE LANGUAGE OF HARPO’S HORN Sometimes Harpo uses his taxi-horn—which sticks provocatively out of his waistcoat, like a misplaced codpiece or a grotesquely swollen belly-button—to announce his entrance and desires, or simply to provide all-purpose indication. As a pronoun points to a prior noun, so Harpo’s horn points to an event in the future or past, or to something manifest that no one else has yet noticed. The horn-honk, intemperate and impertinent, interrupts other people’s speech by making an emergency declaration whose unspecificity is alarming but whose occasional specificity (sometimes we know exactly what Harpo means when he honks) is uncanny. The horn-honk functions equally as unspecified and specified meaning—and we’re never sure which function is being exercised. When called a dummy, Harpo acknowledges disparagement by honking his horn twice. The horn blast contradicts (or confirms!) any statement that precedes it. It performs contradiction and confirmation simultaneously. The honk wipes out—or amplifies—the discourse around Harpo. If you want to be articulate, stay away from Harpo; or else, enjoy nearness to his annunciating honk, and learn how to give blissfully mixed messages.

THE INTERMEDIATE GAZE Curious, Harpo approaches the weeping heroine, played by Mary Eaton, who appeared onstage in the Ziegfeld Follies and died of alcohol-related liver failure in 1948. His face is immobile, but his outstretched eyes look between Mary and the viewer, to an intermediate area that becomes home. He wants to avoid companion or camera, so he focuses on the neutral, interstitial zone, a blankness he recognizes. Has he visited it before? Unable to comfort this fellow loner with words, he provides empty presence. He offers a lollipop that at first she doesn’t see; he gently taps her arm with the candy and mock-licks it, in demonstration. Here is an object he holds orally dear and will provisionally share: this silent kid has transcended the hoarding phase. She refuses the sugary lump on a stick but hugs him in gratitude. (Don’t accept candy from strangers: she has reason to reject a pervert bum’s lure.)

Hugged, he looks again at the intermediate quadrant of respite; arms at his side, posture rigid, he steps back from intimacy, as if to intellectualize and frame it. He recognizes his lollipop-oriented bootlessness. Mary lays her weeping head on his shoulder, but his blank gaze renounces reciprocity. The lollipop scheme failed, and now his stony remoteness—his abstraction—won’t budge. Blankness, however, is soothing, a container for Mary, for melodrama, for failures of every kind, including mine.

CHICO’S FANNY Harpo, mistakenly offended, rotates his arm as a warm-up to a fistfight—but then he interrupts arm gyrations to surprise-kick Chico’s buttocks. With this predictable, repeatable gesture, Harpo gravitates toward the brother’s bottom, reinforces humiliation, and reroutes a fistfight into a butt-kick that conveys no emotion, as if Chico’s fanny, immune to insult, were manufactured from supernatural, nerveless material.

TONGUE BETWEEN TEETH: COZINESS OF CONFINEMENT Locked in a prison cell, Harpo honks his horn (Rescue me!), and flashes a distressed Gookie. No one sees it: Harpo quickly exhausts his repertoire of attention-getters. He tries again: when he bends the prison-cell bars, he giddily sticks tongue between teeth and looks directly at the viewer to say, “Lookie, I did it!” Later I’ll say more about why Harpo sticks his tongue between his teeth. Later I’ll say more about his love of confinement. His goal: to find again a situation he can recognize, and to be recognized, in turn, by that situation, that box, as if it were a human interlocutor. What is recognition? I’ll experimentally define it as a return to a place where one has been known. And yet, by returning, Harpo conjures an original scene of acknowledgment that might never have existed.

We give precedence to words as the proper way to authorize a self. I confess . . . I swear . . . I witness . . . Harpo’s silence gives us “self” as a composition of visual codes—limited, stereotyped, patched together from odds and ends. His father was a tailor. Apparently, not a good one. A tailor’s trade includes piecework, hemming, alterations, and measurements. My father’s father, in Berlin, was a grain middleman. A middleman buys goods and sells them to others, at interest, in installments. Like a pawnbroker, a middleman deals with economic appreciation. My mother’s paternal grandfather, in Brooklyn, was a part-time scholar; in a methodical, fastidious act of mimicry, he translated the first five books of the Bible into Yiddish, and published it as a study book for yeshiva students. Are my mental tendencies—mimicry, middle-manning, appreciation—inherited?

EXTRACTING OBJECTS: MAKING DENTS IN NEARBY CONSCIOUSNESS Harpo, with no apparent comprehension of the written word, hands a deposition to the effete straight man, played by Oscar Shaw (originally Oscar Schwartz), who appeared onstage with Gertrude Lawrence in Gershwin’s Oh, Kay! and died in 1967. Harpo, his lipsticked mouth a Clara Bow rosebud, stands proudly adjacent to a text he didn’t instigate and can’t understand, a document that calls out for his arrest: “Silent, Red, Wanted by the Police.” Objects, including cutlery and an alarm clock, start falling out of his pockets. “I hope I still got my underwear on,” says Groucho, and lo and behold Harpo hands it to him, with a merely informational calm and directness. You asked for it, here it is. I bear no responsibility for the obscene object I’m transferring. Miracle: he steals intimate paraphernalia from Groucho’s body without touching him.

After extracting a hankie by biting it, Harpo looks at Oscar to ascertain: Did I make a dent in his consciousness? Harpo, like an image on a photographic negative, wants to register. A dry-drunk Puck, he leans into Mr. Schwartz and plays fort-da (my favorite game) with the hankie—making it appear and then disappear, for the pleasure of asserting control over an object’s vanishing. To its proper location Harpo restores the hankie and then immediately removes it again. Mid-theft, post-theft, Harpo’s face is empty, passive: he watches his plundering but doesn’t seem to instigate it, as if he were a neutral agent who accidentally catalyzed chaos.

MASTER AND SLAVE, HARPO AND HEGEL Harpo doesn’t want to humiliate others: he wants, like Circe, to undo, inconvenience, discombobulate, and disorient them. His tie is longer and fatter than Groucho’s: brothers mercilessly size each other up. A Harpo rule: lock eyes with the person you’re swindling. His gaze announces to Groucho: I have stolen your tie. I see your shame. Harpo returns the missing tie before Groucho notices its absence. When scolded, Harpo’s mood shifts from satisfied glee to shame or guilt; for an instant, his eyes cast downward. (Harpo’s pattern: head bowed, he laterally pivots his eyes, while other people measure his crimes.) Subordinate once more, Harpo obeys a slave ethic and waits his turn.

Important, no doubt, to Hegel, and to those under his domination, was the notion that a master and slave dialectic drives Western history. Harpo’s body dramatizes these swerves. His up-and-down movement between slave and master acts out a reading of history; the Marx Brothers—conspicuously Jewish, and nominally Marxist—enjoy cinematic fame at a moment in history when the Jews were being tragically thrust downward. Gruesome report: Hitler loved the Marx Brothers. Can one say Hitler loved? Hitler, with his eye of toad, watched Marx Brothers movies.

Harpo steals Groucho’s teeth. While the victim palpates the hollow place in his mouth, the thief smiles, eyes gleaming: in his proud hand he clasps the dental booty, and thus reascends the “topping” or mastery ladder—not just for the pleasure of being a top, but for the pleasure of seeing someone else behave as a bottom.

HARPO’S FORT-DA YO-YO AUTOMATISM At the fancy party, a servant officially announces Harpo’s identity: Ambassador. Of what wandering nation? A jumbo cigarillo hangs out his mouth. In accordance with his fort-da schemes (never let go of an object you can’t immediately wheedle back), his hat, when he drops it, bounces up again with yo-yo automatism. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud used the phrase fort-da (German for “away-here”) to describe a child’s game of making a toy disappear and then expressing delight in its staged reappearance. The child pretends that beloved objects have disappeared into exile, when in fact the child has sent them packing; fort-da is a code phrase for the self’s foundational dependence on vanishing. Objects, to become desirable, must disappear. Existence obeys this periodic rhythm: disappear/appear, there/here. Intermittent invisibilities are the alphabet blocks of my false sense of securely existing here.

CHICO’S HANDSOMENESS Harpo reaches into a punch bowl, scavenges fruit, and slops it into his bacchic mouth. Chico, noticing ingestion, suddenly seems a touchstone of handsomeness. Sexiness, appearing unexpectedly, unsettles; I prefer it to predictable, room-tone, hit-me-over-the-head Hollywood pulchritude. Sexiness should arise from surprise.

HARPO GIVES HIMSELF BREASTS Harpo reenters, wearing Basil-the-basso-detective’s shirt, as the gathered assembly sings “He Wants His Shirt” to the tune of Carmen’s “Habanera.” Harpo’s chest, proudly puffed out, imitates a mammary shelf; with thumbs he further stretches his shirt into fake breasts, although, with honker protruding and cigarillo in mouth, he stakes a phallic claim. He removes the shirt, gives it to Basil, and reaches out to shake his hand—but the offended party doesn’t notice the peace offering. Accustomed to rebuff, Harpo with cigarette/lollipop in mouth gazes perplexedly into his intermediate sliver of respite. How to describe this home-region? Harpo’s gaze always wants to deviate toward that neutral destination, a corner of truce, requiring no eye contact. The comic height difference between Basil and Harpo paradoxically favors the shortie: knowing his smallness, he can make use of it. Basil may be tall, but Harpo, undeterred by his own apparent insignificance, dominates with sombrero and cigarillo. He inconspicuously inserts a bubble in his mouth (I notice only because I’m advancing frame-by-frame); he blows the bubble, which, more Bazooka than smoke ring, steers Harpo back to playland, away from nicotine adulthood. Observe Harpo’s oral inconsequence: while Basil sings, out Harpo’s mouth the compensatory gum-globe protrudes, explanatory as a cartoon’s “thought bubble.” Harpo looks downward at the sphere—a mini-artwork—he happily blows. He looks like an entranced boy in a Chardin painting (The Soap Bubble)—an image of suspended time, of art’s effort to deter movement by making material interventions (bubbles, paint-marks) that seem insubstantial but that convey, in their ephemerality, a buried power. A bubble is the extent of Harpo’s accomplishment, and it is, I believe, monumental.

HARPO’S CODPIECE Harpo finesses “crotch,” that difficult zone. Strange sashes, gathering below his waist, mark his crotch but also turn it into a miasma of visual confusion and excess, prompting the question: what’s going on down there? Harpo’s clothes comically emphasize his phallic side but also reformat it. His sash looks like a postcastration bandage—or a disguise to keep the penis invisible—or a device to emphasize it—or an inventive, unclassifiable development in haute couture.

FLEEING SOMEONE ELSE’S STINK BOMB Listening, at the dinner table, to Groucho’s speech, Harpo finds it so cheesy that he stiffens his shoulders (the “I’ve taken a dump” look), grimaces, chews a cigarette, and eases off-camera, as if holding his nose against the fumes of oratorical offness. He inconspicuously returns to the table and wipes his mouth; off-camera, he took a swig. As Margaret Dumont declaims her speech in stickily operatic recitative, Harpo rises with a semi-Gookie, shoulders hunched, and stands to leave again, moving a few steps toward the exit and then slowly pivoting to look once more at Margaret, whose verbal inauthenticity appalls him. He seems frozen in a wince, as if someone threw a pie in his face—but Harpo himself hurled the banana cream. He holds the wince for an abnormally long beat. Language sickens him. All he wants is food and drink, objects to suck and hold, tasty appendages, costumes he can bend and reinvent. I love Harpo’s “I’m fleeing your stink bomb” semi-Gookie, his face a fixed mask of displeasure, arms monkey-stretched and pendent, fag dangling from his lips, sombrero incongruous. Harpo’s stink bomb–fleeing posture offers a model for righteous, visible protest: he authorizes anyone to skulk away from unpleasant harangues and overblown festivities.

THE “SHOVE-OFF” GESTURE Cyril-the-crook stands to give a toast, whose pomposity Harpo can’t bear: rouged lips spread, teeth clenching a cig, shoulders tightened and hunched, he escapes to the punch-bowl table and aims back to the orator a dismissive “aw shucks” hand movement, which goes unseen.

From TV reruns of the Little Rascals, in the 1960s, my little brother learned a similar gesture: Froggy, a runty, croak-voiced Rascal, waved his hand at an ignoramus and said, “Aw, raspberries,” as if saying “fuck off” or “go fly a kite.” Once, in seismic revolt, my brother said “Aw, raspberries” to my mother. “Aw, raspberries” undermines the potentate with a remark so puny, so comically mismatched to the occasion (raspberries aren’t Molotov cocktails), that the Law can only mope and retreat.

THE STACKING GAME Harpo again returns to the banquet table. His lipstick— reapplied between takes?—looks fruity. He hits his own knee to test its reflex. Then he hits the vamp’s knee. Out pops her leg, which Harpo lays on his lap. Recanting, he gives the “Aw, raspberries!” hand gesture and rests his leg on Chico’s lap instead. Chico refuses the gift, but Harpo tries again. The stacking game has commenced, a pleasurable chance for limbs to echo and confuse: hand, hand, leg, leg. Chico puts a leg on Harpo’s, and Harpo an arm on Chico’s, and eventually their extremities are mutually entangled—an instance of pretzel consciousness. The brothers cram together in symbiotic homeostasis, gaily amniotic, like Tristan and Isolde, or Siamese twins, or death-drive doppelgängers.

To the crowd, Groucho says, “I want to present a charming young lady”; in response, Harpo stands, takes off his hat, and bows, although Chico, disgusted, tells him to sit down. The silent lad eagerly claims any stray designation, even “young lady.”

Inappropriate behavior: last night I dreamt that I threw a filthy party. An unwanted guest dropped food on my grand piano’s keys and clogged the toilet with mechanical objects—hardware not meant to be flushed down.

RECOGNITION Last cameo: all four Marx brothers together face the camera and wave, greeting us. Harpo waves with a limp wrist—signal of babyishness, comfort, soggy boundaries, “cuteness,” exemption. (The gods have granted Harpo amnesty from stiffness.) Limpness causes him no remorse. Waving, the hand moves independently from the wrist. I admire his well-differentiated joints; his body’s tuned elements can wiggle separately, with a temperate, inverted bravura that masquerades as foolishness but transmits unspoken wisdom.

Intercut with the Marx brothers waving is goody-goody Oscar “Schwartz” Shaw embracing Mary Eaton while she sings “When My Dreams Come True.” The film ends with Harpo’s unspeakable dream-wish fulfilled: chance and intrepidity have reunited the far-flung brothers. We celebrate their reabsorption into recognition’s home-like echo chamber. (They recognize each other, and we recognize them: a domino-effect of nods and suturing complicities.)

Harpo has traveled safely through his first talking picture’s terror-strewn terrain. What did he accomplish? (More than I can say.) Harpo proved his flexibility. Harpo demonstrated multijointedness. Harpo threw a Gookie. Harpo stole a hankie. Harpo blew a bubble. Harpo deflected mockery. Harpo transformed humiliation into musical opportunity. Harpo fled someone else’s stink bomb. Harpo stared into space. Harpo looked directly at the camera. Harpo ripped up other people’s letters. Harpo invented a new language.