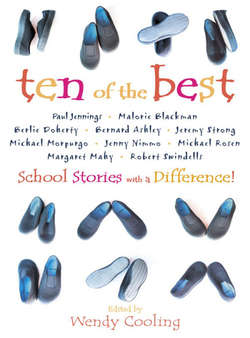

Читать книгу Ten of the Best: School Stories with a Difference - Wendy Cooling - Страница 10

Berlie Doherty The Puppet Show

ОглавлениеIt began with Mickey and Minnie Mouse. My older brother, Denis, gave them to me for my ninth birthday. I had just left the little school in Meols at the time. I loved that school. In winter we had a real coal fire in the classroom, and when it grew dark the flames would flicker shapes and shadows on the walls until the light was put on. You could hear the sea from the yard. In the autumn we gathered chestnuts and leaves from the monkey woods round the school and brought them in to decorate the walls and windows. Some children hardened the chestnuts in vinegar and made holes in them, then threaded them with bits of string for conker fights in the playground. I liked to line mine up on my desk, admiring the way they gleamed like brown eyes. At the end of the day we used to run home along the prom, with the gritty sand whistling round our bare legs, and if there was time we’d play out till dark.

But the autumn term in the year of my ninth birthday had hardly started when the parish priest told my parents that I should be going to a Catholic school, and persuaded them to take me away from there. So I had a long journey by bus to a large flat school in the middle of a modern housing estate. There was a plaster statue of a saint in every classroom. Our room had the Virgin Mary in a blue dress, and she seemed to be watching us all the time with her sorrowing eyes. Occasionally the sickly smell of chocolate drifted in through the windows from the nearby Cadbury’s factory, mingling with the smell of boiling cabbage or fish from the kitchens.

By the time I started there, nearly halfway through the autumn term, friendships had already been made. I was much too shy to talk to anyone, and nobody talked to me. I used to stand in the windy playground with my back against the railings and watch all the children running and shrieking and wonder how there could be so many children in one place, and how they could all know each other. I wished I could squeeze through the railings and run back home. When Mr Grady blew the whistle at the end of playtime the children all froze like the statues in the classrooms, and then at his second whistle they walked absolutely silently into class rows. There wasn’t a child in the school who wasn’t afraid of Mr Grady. His face was cold and hard and white, and I don’t think I ever saw him smile.

One day he caught me reading in a lesson. I was supposed to be doing Arithmetic. I felt his hand coming over my shoulder and too late, he snatched the book away from my grasp and held it up. I was ice-cold with fear. The whole class watched him as he walked with the book to his desk. He had been known to beat children with his cane until they bled. He sat on the edge of his desk and drew a pile of exercise books towards him. Then he rooted through them and drew one out. It was mine.

‘One day,’ he said to the class, ‘this girl will be a writer.’

But I did not feel proud or happy that he had said that. I felt afraid, and ashamed. I hung my head and didn’t look at anyone.

Our class teacher was Miss O’Brien, who had auburn hair like a fox’s back. Her lips were bright red and shiny, as if she was always licking them wet, though I never saw her doing it. I longed to be noticed by her, but she always seemed to be in a dream, gazing out of the window as she taught us, somewhere far away. And around me, the children in the class giggled quietly and passed notes to each other, and shared secrets. They all seemed to be going to each other’s houses for tea or to birthday parties. I was outside it all, just watching.

When my own birthday came around, in November, there was no point having a party. There was no one to invite. So it was a special treat when my brother arrived home unexpectedly, especially as he brought me two presents. ‘I couldn’t decide which one to get you,’ he said. ‘So I got them both.’

They were glove puppets, one of Mickey in a blue smock, one of Minnie in a pink smock with a yellow bow painted on her shiny black rubber head. They both had round beaming cheeks and huge smiling eyes. The heads were hollow, so I could put my hand inside them and bunch up my fist in the cheeks. The smocks covered my hands. I could make the heads bob about and look round and talk to each other. Everybody laughed when I made funny voices and made the puppets talk. I found I could say anything I liked with these puppets on my hands, and nobody minded. I could tell Jean, my sister, that her hairstyle was horrible, or her new dress looked like a sack of potatoes, and as long as I said it in Mickey’s voice she thought it was really funny.