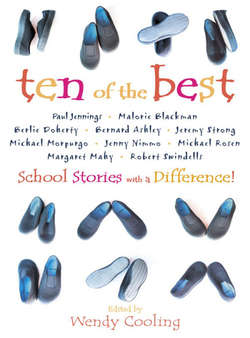

Читать книгу Ten of the Best: School Stories with a Difference - Wendy Cooling - Страница 8

Robert Swindells Porkies

ОглавлениеPiggo Wilson was an eleven-plus failure. We all were at Lapage Street Secondary Modern School, or Ecole Rue laPage as we jokily called it. Eleven-plus was this exam kids used to take in junior school. It was crucial, because it more or less decided your whole future. Pass eleven-plus and you qualified for a grammar school education, which meant you went to a posh school where the kids wore uniforms and got homework and learned French and Latin and went on trips to Paris. At Grammar School you left when you were sixteen to start a career, or you could stay on till you were eighteen and go to university. Fail eleven-plus and you were shoved into a Secondary Modern School where you wore whatever happened to be lying around at home and learned reading, writing and woodwork. You couldn’t get any qualifications and you left on your fifteenth birthday and got a job in a shop or factory. Not a career: a job.

One of the rottenest things about being an eleven-plus failure was that you knew you’d let your mum and dad down. Everybody’s parents hoped their kid would pass and go to the posh school. Some offered bribes: pass your eleven-plus son, and we’ll buy you a brand new bike. Others threatened: fail your eleven-plus son, and we’ll drag yer down the canal and drown yer. But grammar school places were limited and there were always more fails than passes.

It wasn’t nice, knowing you were a failure. Took some getting used to, especially if your best friend at junior school had passed. You’d go and call for him Saturday morning same as before, only now his mum would answer the door and say, ‘Ho, hai’m hafraid William hasn’t taime to come out and play: he’s got his Latin homework to do.’ William. It was Billy before the exam. You’d call round a few more times, then it’d dawn on you that you wouldn’t be playing with William any more. Grammar School boy, see: can’t be seen mixing with the peasants.

Most kids took it badly one way or another, but it seemed to bear down particularly heavily on Piggo. The rest of us compensated by jeering at the posh kids, whanging stones at them or beating them up, but that didn’t satisfy Piggo. What he started doing was telling these really humungous lies about himself. He’d stroll into the playground Monday mornings and say something like, ‘Went riding Saturday afternoon with my grandad, bagged a wildcat.’ He’d say it with a straight face as well, even though everybody knew he’d never been anywhere near a horse in his life and wildcats lived in Scotland. In fact if you pointed this out he’d say, ‘Yes, that’s where we rode to, Scotland.’ Or we’d be listening to Dick Barton on the wireless and he’d say, ‘My dad’s a special agent too, y’know: works with Barton now and then.’ If you pointed out that Dick Barton was a fictional character he’d wink and tell you that was Barton’s cover story. He couldn’t help it, old Piggo: he needed to feel he was special to make up for everybody else seeing him as a failure.

Anyway that’s how things were, and by and by it got to be 1953. There was something special about 1953, even at Lapage Street Secondary Modern School, because of two momentous events which took place that year. One was the coronation of the young Queen Elizabeth at Westminster Abbey. ‘My cousin’ll be there,’ claimed Piggo, ‘she’s a lady-in-waiting.’ ‘She’s a lady in Woolworth’s,’ said somebody: a correction Piggo chose to ignore.

The other momentous event was the conquest of Mount Everest. For decades, expeditions from all over the world had battled to reach the summit of the world’s highest peak, and many climbers had hurtled to their deaths down its icy face. Finally, in 1953, a British expedition succeeded in putting two men on the summit. They planted the Union Jack and filmed it snapping in a freezing wind. The pictures went round the world and the people of Britain surfed on a great wave of national pride: a wave made all the more powerful because it was coronation year.

As coronation day approached, and while the Everest expedition was still only in the foothills of the Himalayas, our teachers decided that Lapage Street Secondary Modern School would stage a patriotic pageant to mark the Queen’s accession to the throne, and to celebrate the dawn of a New Elizabethan Age with poetry, song and spectacle. A programme was worked out. Rehearsals began. An invitation was posted to the Lord Mayor who promised to put in an appearance on the day, should his busy schedule permit.

We failures were excited, not by all these preparations but by the prospect of the day’s holiday we were to get on coronation day itself, and the souvenir mug crammed with toffees every child in the land was to receive. I say all, but it would be more accurate to say all but one of us was excited. While the rest of us laboured to memorise a very long poem about Queen Elizabeth the First and hoarded our pennies to buy tiny replicas of the coronation coach, Piggo Wilson sank into a long sulk because he couldn’t get anybody to believe his latest story, which was that Mount Everest had actually been conquered years ago in a solo effort by his uncle.

He’d tried it on Ma Lulu first. Her real name was Miss Lewis. She was the only woman teacher in our all-boys’ school and she took us for Divinity, which is called RE now. On the day the news broke that Sir John Hunt’s expedition had planted the Union Jack on the roof of the world, she was talking to us about the courage and endurance of Sherpa Tensing and Edmund Hillary, the two men who’d actually reached the summit, when Piggo’s hand went up.

‘Yes, Wilson?’ We didn’t use first names at Lapage.

‘Please Miss, they weren’t the first.’

Ma Lulu frowned. ‘Who weren’t? What’re you blathering about, boy?’

‘Hillary and Sherpa whatsit, Miss. They weren’t the first, my uncle was.’

‘Your uncle?’ She glared at Piggo. We were all sniggering. We daren’t laugh out loud because Ma Lulu had two rulers bound together with wire which she liked to whack knuckles with. Rattling, she called it.

‘Are you asking us to believe that an uncle of yours climbed Mount Everest, Wilson?’

‘Yes, Miss.’

‘Rubbish! Who told you this, Wilson? Or are you making it up as you go along, I expect that’s it, isn’t it?’

‘No Miss, my dad told me. My uncle was his brother, Miss.’ Sniggers round the room.

‘What’s his name, this uncle?’

‘Wilson Miss, same as me, only he’s dead now.’

‘His first name, laddie: what was his first name?’

‘Maurice Miss: Maurice Wilson.’

‘Well I’ve never heard of a mountaineer called Maurice Wilson.’ She appealed to the class. ‘Has anybody else?’

We mumbled, shook our heads. ‘No,’ snapped Ma Lulu, ‘of course you haven’t, because there’s no such person.’ She glared at Piggo. ‘If this uncle of yours had conquered Mount Everest, Wilson, everybody would know his name: it would have become a household word as Hillary has, and Tensing.’

‘But Miss, he didn’t get back so it couldn’t be proved. Some people say he never reached the top, Miss.’

‘Wilson,’ said Ma Lulu patiently, ‘two weeks ago I set this class an essay on the parable of the Good Samaritan. You wrote that you’d been to Jericho for your holidays and stayed at the actual inn.’ She regarded him narrowly. ‘That wasn’t quite true, was it?’

‘No Miss,’ mumbled Piggo.

‘Where did you actually spend those holidays, laddie?’

‘Skegness Miss.’

‘Skegness.’ She arched her brow. ‘Does Jesus mention Skegness at all in that parable, Wilson?’

‘No Miss.’

‘No Miss He does not, and why? Because Jesus never visited Skegness, and your uncle never visited Everest.’ She sighed. ‘I don’t know what’s the matter with you, Wilson: not only do you insult me by interrupting my lesson with your nonsense, you insult those brave men who risked their lives to plant the Union Jack on the roof of the world. Open your jotter.’

Piggo opened his jotter. ‘Write this: I have never been to Jericho, and my claim that my uncle climbed Mount Everest is another wicked lie, of which I am deeply ashamed.’ Piggo wrote laboriously, the tip of his tongue poking out. When he’d finished Ma Lulu said, ‘You will write that out a hundred times in your very best handwriting and bring it to me in the morning.’

We all had a good laugh at Piggo’s expense, but an amazing thing happened next morning. Instead of presenting his hundred lines, Piggo brought his dad. He didn’t look like a special agent, but nobody’d expected him to. We watched the two of them across the yard, but we had to wait till morning break to find out what it was all about. Turned out Piggo’s late uncle had made a solo attempt on Everest back in the thirties and had been found a year later 7,000 feet below the summit, frozen to death. The climbers who found him claimed they also found the Union Jack he’d taken with him, which seemed to prove he hadn’t reached the summit, but the story in the Wilson family was that Maurice had taken two flags, left one on the peak and died on the way down. The climbers had found his spare. The fact that nobody outside the family believed this didn’t worry them at all.

Ma Lulu probably didn’t believe that part either, but she was as gobsmacked as the rest of us to learn that Piggo’s tale was even partly true. She apologised handsomely, cancelled his punishment and used our next Divinity lesson to tell us the story of Maurice Wilson’s brave if foolhardy attempt to conquer the world’s highest peak all by himself We were a bit wary of Piggo after that, but taunted him slyly about his family’s version of the outcome. He stuck to his guns, insisting that his uncle had beaten Tensing and Hillary by more than twenty years.

Our pageant came and went. The Lord Mayor didn’t. He had another engagement but his deputy attended, wearing his modest chain of office. Some parents came too. Piggo’s mum was one of them, which is how we found out she wasn’t a Siamese twin as her son had insisted. On coronation day school was closed. There were very few TVs then, so most people listened to bits of the ceremony on the wireless. Most adults I mean. We kids had better things to do, like setting the golf-course on fire as an easy way of uncovering the lost balls we sold to players at a shilling each.

For us, the best bit of that momentous year came a few weeks later. The Headmaster announced in assembly that a local cinema was to show films in colour of the coronation ceremony, including the Queen’s procession through London in her golden coach, and of the conquest of Everest, compiled from footage shot by expedition members, including the final assault on the peak and views from the summit. Pupils from schools across the city would go with their teachers to watch history being made in this stupendous double bill. There’d be no charge, and our school was included.

We could hardly wait, and Piggo was even more impatient than the rest of us. ‘Now you’ll see,’ he crowed, ‘it’ll show the peak just before those losers Tensing and Hillary stepped on to it and my uncle’s flag’ll be there, flapping in the wind.’ We smiled pityingly and shook our heads, but he seemed so confident that as the day approached, our smug certainty wavered a bit.

It was at the Ritz, right in the middle of the city. A fleet of coaches had been laid on to carry the hundreds of kids from schools all over the district. Ours didn’t arrive first. We piled off and joined a queue that curved right round the building. The class in front of us was from one of the grammar schools so we spat wads of bubblegum, aiming at their hair and the backs of their smart blazers. Red-faced teachers darted about, yanking kids out of the queue and shaking them, hissing through bared teeth, ‘D’you think Her Majesty spat bubblegum all over Westminster Abbey: did Sherpa Tensing spag a wad from the summit to see how far it would go, eh?’ It made the time pass till they started letting us in.

They ran the coronation first. It was quite a spectacle, the scarlet and gold of the uniforms and regalia sumptuous in the grey streets, but it didn’t half go on. We got bored and began taunting Piggo. ‘Which one’s your cousin then, Wilson: you know, the lady-in-waiting?’

‘Ssssh!’ went some teacher, but it was dark: he couldn’t see who was talking. ‘Come on Wilson,’ we urged, ‘point her out.’ Piggo made a show of craning forward to peer at the faces in the procession. There were hundreds. After a bit he pointed to an open carriage that was being pulled by four horses. ‘There!’ he cried, ‘that’s her, in that cart.’ Just then the camera zoomed in, revealing that the woman was black. We shouted with laughter, and Piggo muttered something about having relatives in the colonies. As the camera lingered on her face, the commentator told us the woman was the Queen of Tonga.

The film dragged on. A great aunt of mine, who had a bit of money and owned the only TV in our family, had had people round on coronation day. Those early TVs had seven-inch screens, the picture was black and white, or rather black and a weird bluish colour, the image so fuzzy you had to have the curtains drawn if you wanted to see anything. Coverage had lasted all day, and my great aunt’s guests had sat with their eyes glued to it from start to finish. Get a life I suppose we’d say nowadays, but it was the novelty: none of those people had seen a TV before. Anyway, I was thankful not to have been there.

The Everest film was a great deal more interesting to kids like us. Much of it had been shot with hand-held cameras on treacherous slopes in howling gales so you got quite a lot of camera-shake, but the photographers had captured some breathtaking scenery, and it was interesting to see mountaineers strung out across the snowfield roped together, stumping doggedly upward with ice-clotted beards. Another interesting thing was the mounds of paraphernalia lying around their camps: oxygen cylinders, nylon tents, electrically-heated snowsuits, radio transmitters and filming equipment, not to mention what looked like tons of grub and a posse of Sherpas to hump everything. Brought home to us how pathetically underequipped Piggo’s uncle had been with his three loaves and two tins of oatmeal, his silken flag. Or had it been two silken flags? Underequipped anyway.

We sat there gawping, absorbed but waiting for the climax: that first glimpse of the summit which would silence poor Piggo once and for all, and he was impatient too, confident we’d see his uncle’s flag and be forced to eat our words. It was a longish film, but presently the highest camp was left behind and we were seeing shaky footage of Tensing: ‘Tiger,’ the press would soon christen him, inching upward against the brilliant snow, and of Hillary, filmed by the Sherpa. We were getting occasional glimpses of the peak too, over somebody’s labouring shoulder, but it was too distant for detail. There was what looked like a wisp of white smoke against the blue, as though Everest were a volcano, but it was the wind blowing snow off the summit.

Presently a note of excitement entered the narrator’s voice and we sat forward, straining our eyes. The lead climber had only a few feet to go. The camera, aimed at his back, yawed wildly, shooting a blur of rock, sky, snow. Any second now it’d steady, focusing on the very, very top of the world. We held our breath, avid to witness this moment of history whether it included a silken flag or not.

The moment came and there was no flag. No flag. There was the tip of Everest, sharp and clear against a deep blue sky and it was pristine. Unflagged and, for a moment longer, unconquered. A murmur began in thirty throats and swelled, the sound of derision. ‘Wilson you moron,’ railed someone, ‘where is it, eh: where is your uncle’s silken flipping flag?’

Piggo sat gutted. Crushed dumb. We watched as he shrank, shoulders hunched, seeming almost to dissolve into the scarlet plush of the seat. Fiercely we exulted at his discomfiture, his humiliation, knowing there’d be no more bragging, no more porkies from this particular piggo. The film ended and we filed out, nudging him, tripping him up, sniggering in his ear.

We were feeling so chipper that when we got outside we looked around for some posh kids to kick, but they’d gone. This small disappointment couldn’t dampen our spirits however. We knew that what had happened inside that cinema: the final, irrevocable sinking of Piggo Wilson was what we’d remember of 1953. We piled on to our coach, which pulled out and nosed through the teatime traffic, bound for Ecole Rue laPage. When we came to a busy roundabout the driver had to give way. In the middle of the roundabout was a huge equestrian statue; the horse rearing up, the man wearing a crown and brandishing a sword. Piggo, who’d been sitting very small and very quiet, pointed to the statue of Alfred the Great and said, ‘See the feller on the horse there: he was my grandad’s right-hand man in the Great War.’