Читать книгу Food of Bali - Wendy Hutton - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart One: Food in Bali

Sustenance and sacrifice:

the island cuisine in context

The extravagant beauty of Bali and its vibrant culture first captured the imagination of the world in the 1930s, when it was visited by a few adventurous Dutch colonists, artists and the international jet set (who in those days actually travelled by ship). Since the arrival of mass tourism during the 1970s, hundreds of thousands of tourists have descended upon the "Island of the Gods," yet most leave without having eaten one single meal of genuine Balinese food. How could this peculiar situation have come about?

Bali, then made up of nine separate kingdoms, was conquered by the Dutch in 1908. This was later than most of the other islands of the Dutch East Indies which, together with Bali, now make up modern-day Indonesia. As early as the 8th century, Hinduism and Buddhism arrived on the island. Although Java converted to Islam in the 16th century, Bali has remained to this day staunchly devoted to the Balinese form of the Hindu religion, which continues to govern every aspect of life on the island.

With its volcanoes periodically scattering the land with fertile ash, rivers watering the rice fields and its balmy tropical climate, the Balinese are able to grow a superb array of fresh produce. Food, like everything else in Bali, is a matter of contrast. Just as there is male and female, good and evil, night and day, there is ordinary daily food and festival food intended for the gods. Regular daily food is based on rice, with a range of spicy side dishes including vegetables, a small amount of meat or fish, and a variety of condiments.

Rice and the accompanying dishes are cooked in the morning, after a trip to the market, and left in the kitchen for the family to help themselves to whenever they're hungry. Daily meals, which are eaten only twice a day (with plenty of snacks in between), are not sociable affairs. The Balinese normally eat quickly, silently and alone, often in a corner of the kitchen or perhaps sitting on the edge of one of the open pavilions in the family courtyard. In contrast with this matter-of-fact approach to daily food, food prepared for festive occasions is elaborate, often exquisitely decorated and eaten communally.

Dining out is not a social custom; therefore, unless the visitor is invited into a Balinese home, or samples festive favourites, such as spit-roasted pig or stuffed duck roasted in banana leaf offered at a tourist restaurant, he or she is not likely to experience real Balinese food. Nevertheless, the spices, seasonings and secret touches that make Balinese food unique are just awaiting discovery.

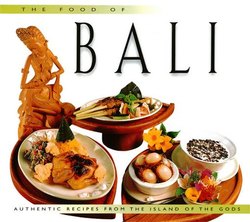

Balinese meal of Sate Lilit (top), Festive Turmeric Rice, Urap and Grilled Chicken (right) and Black Rice Pudding with fresh rambutans (left).

Garden of the Gods

Tropical bounty in the shadow of volcanoes:

geography, climate and cultivation

Bali's landscape is characterized by abundance: thousands of verdant rice fields, graceful coconut palms and a myriad of tropical fruit trees, coffee plantations and even vineyards make up the cultivated areas. On the slopes of the mountains, lush tangles of vines and creepers link huge trees, many dripping with orchids and ferns. It is not hard to understand why the island is often described as "the morning of the world," "island of the gods" and "the enchanted paradise."

Lying between 8 and 9 degrees of the equator, Bali is only 143 kilometres east to west and 80. 5 kilometres north to south. Its extraordinary richness is the result of a combination of factors. The island, and most of Indonesia, lies above the join of two of the earth's seven tectonic plates, and the toweling volcanoes that dominate the landscape are responsible for much of Bali's fertility. Occasional eruptions, while potentially destructive, paradoxically increase fertility as they scatter rich ash and debris over the soil.

Rice terraces cannot function without irrigation. The irrigation cooperatives, or subaks, ensure that sufficient water is available year-round.

The tall mountains (Gunung Agung is 3,142 metres and neighbouring Gunung Batur 1,717 metres) help generate heavy downpours of rain, which collects in a number of springs and lakes. The water flowing down the mountain slopes creates rivers that carve deep ravines as they make their way down to the sea.

Bali experiences two seasons, a hot wet season from November to March, and a cooler dry season from April to October. Long periods of sunshine and adequate rainfall create a monsoon forest (as opposed to rainforest, which grows in tropical regions without a dry season). Natural vegetation, however, covers only about a quarter of Bali (mainly in the west). The rest of the countryside has been extensively modified through cultivation.

The Balinese eat only very small amounts of meat, poultry or fish. Rice is the centrepiece of every meal, accompanied by a variety of vegetables, spicy condiments or sambals, crunchy extras such as peanuts, Crispy-Fried Shallots, fried tempeh (a fermented soybean cake) or one of dozens of types of crisp wafer (krupuk). Although rice is the staple, certain other starchy foods such as cassava, sweet potatoes and corn are also eaten, sometimes mixed with rice, not just as an economy measure (they cost less) but because they provide a variation of flavour.

Many of the leafy greens enjoyed by the Balinese are gathered wild, such as the young shoots of trees found in the family compound (starfruit is one favourite), or young fern tips and other edible greens found along the lanes or edges of the paddy fields. Immature fruits like the jackfruit and papaya are also used as vegetables. The Balinese cook uses mature coconut almost daily, grating it to add to vegetables, frying it with seasonings to make a condiment, or squeezing the grated flesh with water to make coconut milk for sauces that accompany both sweet and savoury dishes.

Although the seas surrounding the island are rich in fish, the Balinese, even those living near the coast, eat surprisingly little seafood. Mountains are regarded as the abode of the gods and therefore holy, while the lowest place of all-the sea-is said to be the haunt of evil spirits and a place of mysterious power. On a more pragmatic level, the coastline of Bali is dangerous for boats and possesses few natural harbours.

The majority of the fish caught are a type of sardine, tuna and mackerel. Fresh fish is available in coastal markets and the capital, Denpasar, but owing to the limited availability of refrigeration, other markets sell these fish either preserved in brine or dried and salted, like ikan teri, a popular anchovy. Sea turtles have long been regarded as a special food and are eaten on festive occasions along the coast and in the south of Bali.

A beautiful tan-coloured cow with a white rear end that makes it look as if it has sat in talcum powder is being successfully raised in Bali, although beef itself is seldom eaten by the Balinese.

Pork is the favourite meat and appears on most festive occasions. Duck is also featured frequently on Balinese festival menus, usually stuffed with spices and steamed before being roasted on charcoal or minced to make satay.

The Balinese eat creatures that not everyone would consider candidates for the table, including dragonflies, small eels, frogs, crickets, flying foxes and certain types of larvae. Visitors are advised to dismiss any preconceptions and sample whatever is offered.

A balmy climate gives Bali an abundance of lush tropical fruit, ranging from familiar bananas to giant jackfruit and thorny durians.

Rice, the Gift of Dewi Sri

Soul food, the life force and

the rice revolution

Terraced rice fields climb the slopes of Bali's most holy mountain, Gunung Agung, like steps to heaven. When tender seedlings are first transplanted, they are slender spikes of green, mirrored in the silver waters of the irrigated fields. Within a couple of months, the fields become solid sheets of emerald, which turn slowly to rich gold as the grains ripen. Although irrigated rice fields cover no more than 20 percent of Bali's arable land, the overwhelming impression is a landscape of endless fertile paddy fields slash ed by deep ravines and backed by dramatic mountains.

Rice, the staple food of the Balinese, nourishes both body and soul. As elsewhere in Asia, the word for cooked rice (nasi) is synonymous with the word for meal. If a Balinese has a bowl of noodles, it's regarded as just a snack-with out rice, it cannot be considered a meal.

Red, black, white and yellow are the four sacred colours in Bali, each representing a particular manifestation of God. Although the majority of rice cultivated on the island is white, reddish-brown rice and black glutinous rice are also grown. The vivid juice of the turmeric root is added when yellow rice is needed on festive occasions.

A big plate of steamed white rice (usually eaten at room temperature) is the usual way rice is presented, although it appears in countless other guises. The most common Balinese breakfast is a snack of boiled rice-flour dumplings sweetened with palm sugar syrup and freshly grated coconut. All types of rice are made into various other sweet desserts and cakes.

Dewi Sri, the Rice Goddess who personifies the life force, is undoubtedly the most worshipped deity in Bali. The symbol representing Dewi Sri is seen time and again: an hourglass figure often made from rice stalks, woven from coconut leaves, engraved or painted onto wood, made out of old Chinese coins, or hammered out of metal. Shrines made of bamboo or stone honouring Dewi Sri are erected in every rice field.

Rice cultivation determines the rhythm of village life and daily work, as well as the division of labour between men and women. Every stage of the rice cycle is accompanied by age-old rituals. The dry season, from April to October, makes irrigation essential for the two annual crops. An elaborate system channeling water from lakes, rivers and springs across countless paddies is controlled by irrigation cooperatives known as subak Consisting of all the landowners of a particular district, the subak: is responsible not only for the construction and maintenance of canals, aqueducts and dams and the distribution of water, but also coordinates the planting and organises ritual offerings and festivals. The subak: system is extremely efficient and computer studies have found that, for Bali, its methods cannot be further improved.

Recently introduced rice varieties dictate that threshing takes place in the field.

Every stage of the rice cycle is accompanied by rituals, some simple, others elaborate, to ensure a bountiful harvest.

An offering to Dewi Sri, the rice goddess, includes a symbolic depiction of the goddess herself A representation of the life force, she is the most widely worshipped deity in Bali.

The so-called rice revolution has had an enormous impact on Bali, as it has on all Asian rice-growing countries. For more than twenty years, the International Rice Research Institute, headquartered in the Philippines, has been developing high-yield rice strains resistant to disease and pests. Bali's traditional rice variety, beras Bali, is a graceful plant that reaches a height of around 1.4 metres. It has a superior flavour and many Balinese willingly pay up to four times the price of ordinary rice for it. But the most widely used new rice in Bali is the unimaginatively named IR36, developed by the IRRI.

This so-called "miracle" rice takes roughly 120 days to mature compared to the 150 days required for beras Bali. It is now grown in 90 percent of Bali's rice fields. Traditionally, the long stems of beras Bali were tied together in sheaves, carried to the granary for storing, then pounded in a big wooden mortar to dislodge the husks when rice was needed. The stems of IR36, however, are short (half the height of beras Bali) and the grains easily dislodged. Thus, threshing has to take place immediately after harvesting. Certain traditional rice harvesting practices, including the construction of granaries, are dying out with the introduction of the new varieties. The Balinese acknowledge the superior yield and growth rate of the new plants: in 1979, Bali almost doubled the amount of rice it had harvested a decade earlier.

Since 1984, Indonesia has been able to provide sufficient rice to feed its burgeoning population and can now concentrate on developing varieties better suited to local conditions. The Department of Agriculture is now experimenting with rice strains that can, it is hoped, eventually be reconciled with the basic foundations of Balinese culture. Dewi Sri, it seems certain, will continue to be honoured and her blessings sought for many more generations.

Daily Life in Bali

Harmony and cooperation within

the village compound

The rhythm of the day in a typical Balinese family compound is ruled by the rice harvest, governed by tradition and watched over by the gods. Several generations usually live together in the compound, which is laid out in accordance with esoteric Balinese principles and surrounded by a mud or brick wall. The holiest part of the land (that which faces the mountains) is reserved for the various shrines honoring the gods and ancestral spirits.

Beyond this enclosed area are a series of other pavilions or rooms used as sleeping and living quarters, with the kitchen or paon and the bathroom near the least auspicious part of the property-that closest to the sea. Farthest of all from the holy area one finds the family pigsty (there is always at least one occupant being fattened up for the next important feast) and the rubbish pit.

Flowering trees and shrubs (a source of blooms for the daily offerings) are dotted about the compound, while the gardens at the back often contain several fruit trees: papayas, bananas (their leaves essential for wrapping food) and coconut palms, among others.

The women are always occupied, cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, sweeping and preparing offerings. Older women often take the daily offerings around the compound, setting them before the various shrines before anyone has their first meal of the day, as well as performing other tasks, such as feeding the pigs, weaving offerings, making special rice cakes and keeping an eye on the youngest children.

The old men who are no longer fit for work in the fields pass the day slicing strips of bamboo and shaping them into baskets, repairing tools or utensils, and doing odd jobs about the yard. When nothing remains to be done, or they feel like taking a break, they wander off to a nearby wan mg (simple local store) for a cup of coffee and a chat with friends.

Towards the end of day, when it's cooler and the younger men have returned from the fields, they may all gather to watch a cockfight. Although gambling is forbidden throughout Indonesia, there's always a corner of every village where this traditional sport goes on, with scant regard for the law.

Making the daily offerings in the family compound.

The market at Denpasar, Bali's capital, is the largest and most colourful on the island.

A chilli vendor in the vegetable market at Batur sorts her wares.

Young girls learn the tasks of a woman in the same way they learn to dance-by imitating their elders from a very early age and perfecting technique over time. The bale gede is usually where women gather to prepare temple offerings, including weaving young coconut palm leaves into trays, baskets, or complex hangings.

This pavilion is also where utensils and other objects involved in worship are stored (generally in the rafters) and where ceremonies involving rites of passage, such as weddings and tooth filings, take place. (The Balinese abhor pointed canine teeth, which they say makes them look like animals, and they are filed down by priests usually when youths reach puberty.)

Culinary skills are passed on from mother to daughter down the generations. Girls frequently undertake the daily task of peeling shallots and garlic, slicing and chopping seasonings, and grinding spice pastes with a mortar and pestle. They are also entrusted with cutting banana leaves and trimming them into shape so that they can be filled with food, folded and secured with a sliver of bamboo.

The complex ingredients for Balinese food and ritual offerings are all committed to memory. No Balinese woman ever needs to consult a cookbook for a Balinese recipe, although a modern woman might follow a recipe for dishes from other Indonesian regions.

Many families now have television sets, and most bale banjar, or community centres, also have a set where anyone can gather to watch programs in Indonesian, English or Balinese. Early evenings are also the time when the various cooperative organisations meet for discussions and planning, and there are also informal "drinking clubs," where the men meet over a glass of tuak (palm brew).

By about 9 pm, doors of the enclosure are closed against any malign spirits that may be wandering in the night, and the only lights to be seen in the village are those of twinkling fireflies.

At Home with Ibu Rani

A day in the life of a Balinese cook

Mangku Gerjar, an elderly priest from the village of Ubud in central Bali, lives with his extended family in a typical compound. The compound houses a total of thirteen people: he and his wife, Ibu Kawi, their three married sons, and their wives and children. Mangku Gerjar's youngest son, Nyoman Bahula, and his wife, Rani, are modern Balinese, having only two children, Rudi and Lies.

In the morning, once the children have gone to school, Ibu Rani sets off to market. (Ibu, a polite Indonesian term of address for a married woman, is not actually used among the Balinese, who have a very complex system of names.) By 7 am the market is already crowded. Rani bypasses mounds of brilliant flowers and coconut-leaf offering trays to select a few pounds of purple-skinned sweet potatoes. From piles of vivid leafy green vegetables, she picks out a couple of bundles of water spinach or kang kung Next into the shopping basket goes a paper twist of raw peanuts and a leaf-wrapped slab of fermented soybean cake (tempeh).

Rani pauses by some enamel basins full of fish in brine, changes her mind and settles for a bag of tiny, frantically wriggling eels caught in the rice fields, then goes to the meat stall and buys a piece of pork and a small plastic bag of fresh pig's blood.

The basics of today's meals already purchased, Ibu Rani heads for the spice stalls. Mounds of purplish shallots, pearl-white garlic and chillies ranging from long red tabia lombok to the popular short, chunky red and yellow tabia Bali, fiery little red and green bird's eye chillies, compete with piles of innocuous-looking roots hiding their rich fragrances. There's familiar ginger; its relative, galangal or greater galangal; camphor-scented kencur (Known to the Balinese as cekuh), with its white, crunchy and flavoursome flesh, and finally vivid yellow turmeric, the most pungent of all.

Fragrant screwpine or pandanus leaf, the faintly flavoured salam leaf, the small but headily scented kaffir lime and its double leaf, spears of lemongrass and sprigs of lemon-scented basil, all promise magic in the kitchen. Like the emphatic tones of a large gong, the odour of dried shrimp paste from a nearby stall assails the senses.

Ibu Rani (right) with Mbok Made (left) and Kadek Astri Anggreni (centre) weaving a jejaitan from palm leaves in their Ubud family compound. The jejaitan is the base mat upon which temple offerings are placed.

Grating coconut and grinding spices can be lime-consuming unless such tasks are shared.

Ibu Rani pauses for her daily glass of jamu, a herbal brew which she says keeps her body "clean inside," then buys breakfast for herself and her husband: a few small moist rice cakes or jaja, sprinkled with fresh coconut and splashed with palm sugar syrup. Hoisting her basket onto her head, Rani then walks home.

Within the compound, sounds of grinding can already be heard from the other two kitchens. Pulling out the morning's purchases, Rani gets to work, peeling and chopping seasonings for the leaf-wrapped food tum. "I make tum almost every day," she explains. "Sometimes it's with eels, with a little meat or perhaps some chicken. Today, I'm going to use pork."

An earthy smell permeates the kitchen as she finely chops shallots, ginger, garlic, chillies, fresh turmeric, kencur roots and salam leaves. Next, she removes scraps of gristle from the piece of pork and throws them out for the chickens. The pork is then deftly minced into paste with a cleaver, and mixed with chopped seasoning, a big pinch of salt, a splash of oil and the pig's blood.

Large spoonfuls of this mixture are spread onto a square of banana leaf, carefully folded, then secured with a slender bamboo skewer. By this time, the rice-which had slivers of sweet potato added halfway through cooking-is turned out into a colander. The leaf-wrapped bundles of pork are set in the same steamer used for the rice and put over boiling water to cook.

Pulling out her saucer-shaped stone mortar, Rani gets ready to grind the spices for seasoning the tempeh. "Don't bother to peel the garlic," she cautions, "there's no need, the skins will fall off when it's cooking." Like most Balinese cooks, she sees no need for fussy refinements.

The ground turmeric root, garlic, salt and white peppercorns are mixed with a little water and massaged into the protein-rich tempeh, which is left to stand for about half an hour before frying. Rani fries the peanuts in her wok, reserving some as a crunchy garnish and then grinds the remainder with toasted shrimp paste and chillies to make a tangy sauce to be mixed with the blanched green vegetable (kangkung). The eels are drained, salted and cleaned before also being fried in hot oil. Their crunchiness and flavour is later improved by tossing them in the wok with chilli paste.

Finally, everything is cooked and ready. The colander of rice is covered and left on the bench, and the remaining dishes set in a cupboard for family members to help themselves to throughout the day.

Lavish Gifts for the Gods

Festival foods serve as offerings,

works of art and meals for mortals

Food in Bali is literally deemed fit for the gods. Every day of the year, the spirits whose shrines occupy the forecourt of every Balinese family compound are presented with offerings of flowers, food, holy water and incense. The offerings serve to honour the spirits and ensure that they safeguard the health and prosperity of the family. Even malicious spirits are pacified with small leaf trays of rice and salt, which are put on the ground. These simple offerings are, with out fail, presented before the whole family eats their first meal of the day.

At more elaborate temple festivals, brilliantly dressed women form processions as they bear towering offerings of fruits, flowers and food upon their heads. These elaborate temple offerings are virtually works of art, but have a deep symbolic significance that goes far beyond mere decoration.

A seemingly endless round of religious and private family celebrations ensures that the women-whose task it is to prepare such offerings-always spend some part of the day folding intricate baskets or trays, or preparing some of the more than sixty types of jaja or rice cakes essential for festivals. Young girls sit beside their elders who pass on the intricate art of cutting and folding young coconut-palm leaves, moulding fresh rice-dough into figures, colouring rice cakes and assembling the appropriate offerings for each occasion. Women working outside the home may purchase their offerings from a specialist tukang banten in a market, but they never fail to observe their ritual obligations.

Temple festivals and private celebrations, such as weddings or tooth filing ceremonies, don't just provide food for the gods-the mortals also get their share. Offerings brought to a temple are first purified by the priest, who sprinkles them with holy water while chanting prayers. Once the "essence" has been consumed by the gods, the edible portions are enjoyed by the families who brought them. Any stale leftovers, less-tasty morsels and stray grains of rice are eagerly consumed by the dogs, chickens, wild birds or even ants. Nothing goes to waste.

Food art for the gods. A festival offering made from rice dough.

Everyone works together to prepare festival food.

Apart from temple offerings prepared for the gods, special ritual foods are cooked solely for human consumption on important occasions. These foods are generally complex and require an enormous amount of cooperative effort to prepare. The Balinese, who normally eat very little protein food with their daily rice, consume comparatively large amounts of meat (generally pork or, in the south of the island, turtle) during festivals. Such feasts are a time for eating communally, generally seated on a mat on the ground of the temple, or within the family compound.

For a small family celebration, the food is prepared by the family involved. Larger feasts involve the whole banjar, or local community, the work being supervised by a ritual cooking specialist, who is invariably a man. There is a strict division of labour, with men being responsible for butchering the pig or turtle, grating mountains of coconuts and grinding huge amounts of spices: all tasks which require considerable physical effort. The women perform the fiddly task of peeling and chopping the fresh seasonings, cooking the rice and preparing the vegetables.

The most famous festive dish is Lawar (recipe on page 98). This is basically the firm-textured parts of a pig or turtle cut into slivers, mixed with pounded raw meat and fresh blood, and combined with a range of vegetables, seasonings and sauces. To Western tastes, the number of fiery hot chillies that goes into the lawar makes it positively incendiary!

A day before the lawar is prepared, the mammoth task of peeling hundreds of shallots and cloves of garlic, and scraping turmeric, galangal and kencur roots has already begun, so that before dawn on the day of the festival, the preparation of the lawar can begin. A whole pig (generally raised at the back of the family compound) or a turtle is slaughtered, and some of the choicest meat is kept aside for chopping into a fine paste. The blood is also kept, mixed with lime juice to prevent it from coagulating. Another essential ingredient is a tough portion-if it is a turtle, it will be slivers of boiled cartilage, while in the case of a pig, the boiled ears-which is very finely shredded.

Unless the lawar is being prepared for a huge number of people, there will be plenty of leftover meat, which is prepared in a number of different ways: cooked with sweet soy sauce (kecap manis), simmered in a spicy coconut milk gravy and pounded and mixed with grated coconut and spice paste to make satays. Scrappy bits of pork are chopped finely, seasoned and packed into the reserved intestines and crispy fried to make spicy sausages.