Читать книгу Modern Alchemy and the Philosopher's Stone - Wilfried B. Holzapfel - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe afternoon sun beamed down on Helen as she sat on the library steps waiting for Marie. The air was crisp and dry, a perfect autumn day. It was the kind of day that the people in the eastern part of the U.S. call “Indian Summer.” In this expression, the term Indian refers to the Native Americans who lived in the area before the arrival of the Europeans. Helen thought about the life style of the Native Americans. Did they also practice a form of alchemy? After all, much of the philosophy that formed the esoteric path of alchemy appears to have originated in China and India. Helen knew that the Native Americans had not come from India. But recent DNA analyses3 have confirmed that the earliest Americans had descended from populations in China and eastern Asia. On the other hand, that was thousands of years before the earliest recorded thoughts of alchemy in the western world. Was there anything that might be considered to be the Native American equivalent of medieval alchemy?

Before she started college, Helen had visited Montezuma Castle on a family vacation trip to northern Arizona. Early Spanish explorers of the area had mistakenly associated the impressive cliff dwelling with the Aztec emperor of Mexico. Later research has attributed the design and construction of the “castle” to the Sinagua tribe. The structure was fully occupied between 1100 and 1400 A.D. Helen had been particularly struck by a timeline display in the modern museum on the site. It showed what was happening in Europe while the Sinagua were busy farming the area around Montezuma Castle. While the Americans were building with clay and making tools of bone and stone, the European’s were building the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris! Roger Bacon had sent his scholarly categorization of alchemy, his Opus Majus, to the Pope Clement IV in 1267. Clearly there was no link between formal exoteric alchemy and the scientific thoughts of the Sinagua.

As she watched Marie walking toward her along the college “Quad,” Helen concluded that any direct connection between the philosophy and religion of the European alchemists and that of the Native Americans was quite unlikely. Still, she speculated, if there were any similarities they might be very fundamental to an understanding of human development and spirit. She made a note to herself to keep this thought in mind for a future paper that she might have to write in a more advanced Philosophy course.4

“Hi, Helen,” Marie called out as she approached. “What a fantastic day!”

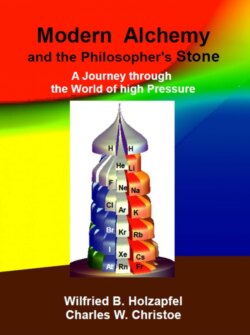

“A day custom-made for us by Zeus and Hera themselves,” Helen responded, specifically referring to the Greek gods of the Sky and Air who were the head of all the other gods of weather, the so called Theoi Meteoroi. Helen was beginning to get quite wrapped up in this Greek Philosophy thing. She picked up her book-bag and the two of them set off in the direction of Faculty Row, both eagerly anticipating the progress that the professor might have made on his United States of the Elements.

Their anticipation was rewarded by the sight of Professor Wood busily at work on his sculpture.

“Hello, Professor,” Helen yelled out once she was within earshot of the site.

The professor turned with a welcome smile toward the approaching students. He had made some noticeable progress in his work. The top two rows of the spiral were now clearly visible below the odd Moorish-looking cap at the top of the column. The professor had marked radial lines on the surface of the spiral and had chiseled off the outer edge of the top row, forming a rough representation of the irregular “teeth” that they both recalled from the illustration that Professor Wood had shown them earlier. The three-dimensional model itself stood on a small collapsible table near the main work. Two pairs of calipers lay on the table near the model.

“Wow!” Marie exclaimed. “It’s coming right along.”

“Well, thanks,” returned the professor, “but I still have a long way to go.”

“Of course,” said Marie, as the students admired the work in detail. “I have a question,” she continued. “Why are the teeth not all the same? Some stick out further than the other and have different shapes to their upper surfaces.”

“That’s because they are not actually teeth. Each tooth, as you call it, represents a different element of the periodic table.” He held up the model to show them. Actually, each of these segments is a three-dimensional representation of the effects of temperature and pressure on the element to which it corresponds.”

That was too much for Helen. “Wait a minute,” she interjected. “Didn’t you say that the philosophy underlying the architecture was based upon alchemy? Marie and I have been reading up on alchemy so that we would have a better chance of understanding what you are doing. I don’t get the connection.”

“Yes, I did use the word alchemy, modified by the adjective ‘modern’ – modern alchemy, I said. I hope I have not misled you too much. What have you learned about alchemy since I first met you?”

Marie took this opportunity to jump into the conversation. “We learned that unlike the many elements you have in your model, the ancients recognized only four elements, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. Their sculpture would have been a lot easier to carve,” she grinned.

“I suppose so,” the professor agreed. “Actually, those four terms referred more to the fundamental characteristics of matter than to the basic chemicals we think of today. But it is true that the ancients thought of all physical materials as being composed of a combination of these four primary components. Have you seen any representation of an alchemist’s Table of the Elements?”

“I have one here in my phone.” Marie reached into a pouch on her book bag and extracted the device. “How about this one?” She showed him the simplest of the pictures she had downloaded. (Figure 4) “I found it at the Alchemy Website,” she said.