Читать книгу Modern Alchemy and the Philosopher's Stone - Wilfried B. Holzapfel - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление“That’s it!” beamed the professor. “You can see how the symbols for male and female, the sun and the moon, have been inserted into the overlapping triangles in the center of the figure. There is also a larger triangle around the central one that contains the symbols for salt, sulfur and mercury.”

“What are these words around the outside the triangle that includes the large triangle,” Helen wanted to know. “Are those Latin words? I recognize the word Principia, meaning principles.”

“Actually, the other two are German words that complete the phrase, Die drei Principia, as we would write it today. It refers to the three principles that describe the way that naturally occurring materials have been formed. Salt, sulfur and mercury are examples of those principles. I see that someone has added the characterizations of the most common chemical bonds that we understand today. Was that you, Marie?”

“Oh no,” Marie protested. “They were already there when I downloaded the figure from some website that I had found.”

“Whoever that was might also been thinking of the connections between ancient and modern alchemy.” The professor glanced back at Helen. “Are you familiar with the differences between these three kinds of chemical bond and the way that these three substances exemplify them?”

“I am,” Helen assured him. “I took an advanced chemistry course in high school.”

The professor expressed his surprise at this. “I would say that was quite practical for a future student of Philosophy.”

“It got me out of having to take a laboratory science here next year. Besides, I also want to prepare for a minor in secondary education and I figured it could come in handy.” Helen changed the subject. “While we are on the subject of Philosophy, it seems to me that this figure emphasizes the exoteric part of alchemy. Will your sculpture contain something of the esoteric part? Will it also represent some of the more spiritual ideas of the alchemists that have remained with us through the years?”

The professor thought for a moment about Helen’s questions. “Certainly my research has centered on laboratory research and the scientific method,” he said. “But now that you mention it, the sculpture does have the form of spire. It has the appearance of a kind of ‘stairway to the stars,’ as the saying goes. You might say that it points to the sky, or the heavens, or to the infinity of space beyond them. Certainly, I have intended for it to be artistic, uplifting and inspirational to young people such as you and Marie. Perhaps there is more to this shape than I had originally intended.”

Helen seemed satisfied with this response for the time being. She returned to the diagram on Marie’s smart phone. “What are these words just inside the outer edge of the figure?” She read clockwise, pronouncing each word distinctly and deliberately: “Sum, Cha, Os, and Confu. I recognize the Latin words for I am and bone. Does Cha mean tea in Latin like it does in Chinese? I am tea and bone? Basilius Valentinus might have been familiar with Chinese tea, but I doubt that he could have anticipated the recent CONFU or Conference on Fair Use of the internet that would take place hundreds of years later.”

The professor laughed. “Let me help you out,” he said. “Suppose I group the four words into two – as in Confusum Chaos.” Does this suggest anything to you?”

“Chaotic confusion?” Helen ventured. “Perhaps something like random things fused together?”

The professor nodded. “That sounds about right. It refers to the formless matter that existed before the universe assumed the form that we recognize today, the surrounding chaos”

“Before the Big Bang!” Marie exclaimed.

“Let’s say ‘just after the Big Bang,’ according to more modern theories.” The professor went on to explain. “Actually, one way to read the illustration is to start at the outside and proceed toward the center. Out of formless matter, the universe became organized into four basic elements which combined according to three basic principles into the perfect union between woman and man.”

Helen and Marie looked at each other and giggled. Not much about the union between woman and man was perfect in the movies and TV shows they had seen. Presumably that was also true in the Middle Ages. But then, it was the goal of the two entwined paths of alchemy to achieve perfection. The big question was how to get there. Is that what the professor’s stairway to the stars supposed to show: a spiraling path to perfection?

Helen was about to ask the professor about that when he glanced at his watch and announced, “You’ll have to excuse me, ladies. I see that is time for me to go help prepare dinner for my wife and myself. You really should make an appointment to see me in the office. I can show you more about the information contained in the sculpture. There is a sign-up sheet on the door.”

“I hope that your dinner is more perfect than ours is likely to be,” Helen said somewhat absent mindedly.

Professor Wood gave her a quizzical look and bid them adieu. He turned to gather his tools and to place the model sculpture into a box that had been padded to receive it. Helen and Marie continued on their way to the dorm.

As they walked, Helen told Marie about her interpretation of the spiral stairs on the model sculpture. “Do you think that the sculpture is supposed to be a path to heaven?”

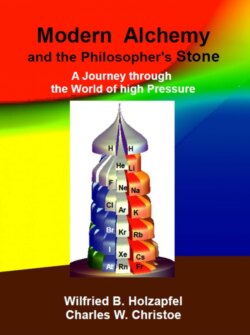

“I think that is unlikely,” Marie responded. “Remember that he told us that each step represents a specific element in the periodic table. The shape of the step has something to do with the physical properties of the element in its pure form. Plus, you would have to start at the bottom with the most complex elements and work your way up to the simplest one, ending with Hydrogen. Okay, maybe Hydrogen does represent a kind of simple perfection that the ancients never dreamed of. But why would he carve a cap on the top of the spire that separates the path from the cosmos?”

Helen thought about the cap at the top of the model. It looked like a mushroom to her. She shuddered at her next thoughts: Hydrogen, mushroom. “Marie, what if the cap is supposed to be a mushroom cloud! What if the professor is showing us a short-cut to infinity via a nuclear disaster?”

“Helen! Get a grip on yourself. The guy is a Professor of Physics, not a global terrorist!”

“How can we be sure?” Helen asked with a wild-eyed look.

“I’ll tell you what,” Marie said in a soothing tone. “I’ll sign us up for an office visit. Maybe you can think of a few questions to ask him that will put your mind at ease.”

The next day, Marie went to the Physics Building on her way to her first class. She signed in for the first available office hour, late the following afternoon. As she headed for the exit to the Quad, she happened to see Professor Wood on his way into the building.

“Have you signed up for an office hour?” the professor asked.

“I have. I figured it was time. Helen thinks that you are planning to blow up the world”

Professor Wood roared with laughter. “It is definitely time for an extended chat,” he agreed.

Several other students on their way to physics classes turned to catch the usually serious-minded professor in such a jovial mood.

Later that day, as Marie entered the cafeteria, Helen was just coming out.

“Oh, by the way, I signed us up for Professor Wood’s office hour tomorrow afternoon! I almost forgot to tell you,” Marie said. “Let’s meet in front of the Library and go over to the Physics Building together.”

“See you there!” Helen replied with a bright smile.

The two young women met as planned the next afternoon and arrived punctually for their meeting in the professor’s office.

The professor was smiling as he responded to their knock on the door. “Please come in. May I offer you some coffee or tea?”

“Or maybe some confusum chaos,” Helen suggested testily.

The professor chuckled at Helen’s expression. “Your friend here tells me that I may have misled you by possibly overstating the connection between my sculpture and alchemy. I suggest that we spend this meeting clearing up some of the confusion – by which I do not mean confusum chaos.”

The professor offered a tray of assorted tea bags and K-cups of coffee, which the students respectfully declined.

“Let me set aside the references to alchemy for a while,” the professor began apologetically. “I would like to offer you an alternative analogy to the form and

purpose of my sculpture. Let me compare it to a globe, like the one here on my bookcase.

“I sometimes think of my sculpture as providing an overview of the way matter is organized in much the same way that a globe of Earth shows where there is water, where there is land and how the different countries and cities of the world are laid out on the land masses.

“Of course, if we want to know about a single country, we need more detailed maps, picture books or guides. Still, the globe gives us a high-level view of what is going on. We can see which countries fit together, which countries are in hot or cold zones and where to find mountains or deserts. It is important to know these things before we set out to explore the world!

“My United States of the Elements shows a certain order for the chemical elements that we would need to know about if we would like to take a journey through the world of high pressure physics. Just as a globe identifies the different landscapes so that we can recognize where we are and where we are going, this three-dimensional figure can help us find our way in this new world of high pressure.”

Helen interrupted with a surprising outburst, “Pressure! What’s that got to do with travel? What kind of pressure are we talking about here?”

Marie tried to calm Helen down. “I just learned something about pressure in my physics class last month. We all use the word pressure to describe what we feel when someone pushes on our arm. Sometimes we use the word more abstractly to describe how we feel when we have a lot to do or when we have several assignments due on the same day. It turns out that in physics, the word pressure has a very specific meaning. It is defined as an amount of force divided by the area over which the force is directed. If you want to create a large amount of pressure over a large area, you will need a lot of force. But if you are only interested in a very small area, you can create the same amount of pressure with just a little force. You can feel the difference when I press on your arm with just my thumb instead of using my whole hand.”

Helen reflected for a few moments on Marie’s explanation of the definition of physical pressure. Suddenly she recalled something that the professor had said when she first asked him about the sculpture. “I get that part, Marie. We also touched upon that definition of pressure as a thermodynamic variable in my advanced chemistry course. But now I am thinking about something that Professor Wood said earlier about the sculpture. Professor Wood said that his model is actually a three-dimensional representation of the periodic table, the chart of the elements. He told us that the model displays more information than the usual two-dimensional variety. What I don’t understand is why you need a globe to take a trip across the periodic table that hangs in the chemistry room.”

“That is exactly what I told you,” said the professor. “I would say that the reason for having a three-dimensional chart of the elements is more or less the same reason that there is a globe in the geography room as well as a flat map of the world hanging on the wall. Magellan would have been in a lot of trouble sailing to the edge of the map if he hadn’t already seen a globe!”

Helen remained more than a little perplexed. “I still don’t understand what pressure has to do with it,” she said. “The elements are still going to be the same elements whether there is pressure on them or not, aren’t they? We no longer believe that there is any hope of changing one element into another simply by applying external pressure to a specimen made up of a single type of atom. I’m guessing that the ancient alchemists also tried squeezing on lead to get it to change into gold – and we know that they were unsuccessful in those attempts.

“From the little that I know of the atomic theory of matter, the forces inside the nucleus – the ones between the protons and neutrons that largely determine what element the atom represents – are very much larger than the forces that the atoms exert on each other or the forces those atoms are likely to experience in an ordinary college research lab. It’s hard for me to imagine that even modern alchemists can hope to achieve of those kinds of forces and pressures in a college laboratory. Am I right about that, Professor?”

“Well, yes, you are absolutely correct, Helen,” the professor replied. “But I might add that we are able to apply significantly more pressure to materials these days in our college research lab than the alchemists were able to produce using the apparatus that appeared in the drawing of the Alchemist’s Kitchen (Figure 2) that Marie showed us on her phone. Not only are we able to apply more pressure to the materials, but with a little help from my Philosopher’s Stone here, we are able to extract information about the materials while they are being subjected to high pressure. So even if we are also not able to transmute lead into gold, we may be able to get one element to take on the appearance and some of the other characteristics of another element.”

The professor picked up a strange-looking contraption from his desk. “I’ll explain more about this another time. But to continue the discussion about the relevance of pressure, we notice that at higher pressures the interaction among atoms does change as we apply more and more pressure. If I may go back to the analogy of a globe, I might compare the changes that we have been able to observe in materials to the way the continents change over time due to plate tectonics – or maybe the way politics and war change the shape of countries and the importance of certain cities. Maybe it is some of both. In any case, there are aspects of the way the elements respond to applied pressure that the alchemists would find to be very interesting.”

Marie was anxious to rejoin the conversation. “Are you saying that the changes that some of the elements undergo in the presence of high pressure are such that those materials exhibit different physical properties? Does that mean that, even though one element does not actually become another, it might have the same physical properties under high pressure as has another element? And are you suggesting that your sculpture is somehow able to portray those similarities?”

The professor’s eyes widened at this. Marie’s questions implied a level of perception that was rare among any of the students he had known – far less among first-year college students. He complimented her on her observations, both of which were right on the mark!

“That is very close to what I was hoping that the sculpture would show,” he told her. “That, and a bit more. What I have tried also to capture is some of the significant trends and links that appear within groups of related elements. As I said earlier, the sculpture has much in common with the two-dimensional table of the elements. The way that certain groups of elements behave suggests an underlying principle that is common to that particular group. It’s a little like the way some games have hidden rules that are not visible for a simple spectator of the game. For the initiated player, these rules contribute to the charm of the game. When it comes to the chemical elements, the rules of nature act as lighthouses to help keep us on course.”

“I guess that brings us back to the notion of maps, globes and travel,” Helen interposed. “Is that as far as your travel analogy goes? Your last statement is pretty ambiguous. Even modern day navigators no longer rely upon lighthouses.”

The professor smiled. “There is another analogy that I like to make with regard to travel and global exploration,” he said. “The white spots on the globe today represent only uninhabited fields of ice that are well-defined and charted. In the past, the white areas corresponded to unexplored regions of the globe, but today there is no terra incognita, or unknown land, left anywhere on Earth. You can find satellite images of any place on Earth using Google Earth View! But, on my map there are still other worlds left to explore! The world of high pressure is full of examples. I think that, using different pictures and examples, I might be able to prepare you for a journey through my world of high pressure. You might even want to explore some of the terra incognita we encounter along the way.”

Professor Wood thought that perhaps he had seen Marie stifle a yawn. “Are you sure that you would not like some coffee or tea?” he asked politely.

This time, both students nodded in the affirmative. The professor excused himself to turn on his teapot and set out a mug for each of them. Helen and Marie exchanged glances as the professor placed a mug in front of each of them. The mugs had a peculiar design on them. The design was a “wrap around” of a smaller version of the colorful chart that hung behind the professor’s desk. Both of them had noticed the chart as soon as they had entered the room. It looked a little like the periodic table of elements that had been so much the focus of the conversation for the past half-hour, but the space dedicated to each element contained a blotch of different colors.

A whistle from the teapot signaled the completion of the first step in the preparation of their refreshments. Again, the professor offered the mixed tray of teabags and condiments, plus an attractive plate of sugar cookies. After all, it was getting to be late afternoon!

This time Marie broke the silence as a teabag sank beneath the surface of the water in her decorative mug. “May I infer, Professor, that the white spots on this mug (Figure 6), and those on the chart behind your desk, (Figure 7) correspond to the “uncharted territory” that is still left to be explored on the map of your world of high pressure?”