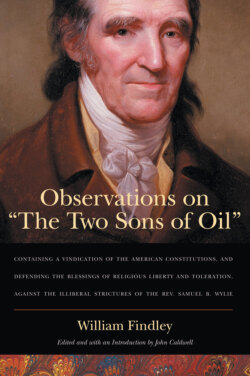

Читать книгу Observations on “The Two Sons of Oil” - William Findley - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER I

The text explained—Of the moral law of nature—Of positive laws—Penalties to be executed by man, belong to positive law—Civil government founded on the law of nature—Peculiar law of Israel, positive and abolished—Christ’s delegated power examined—The magistrate’s power to ratify and sanction the laws of the Most High God examined.

The Reverend Author of “The two Sons of Oil, or the faithful witness for ministry and magistracy upon a scriptural basis,” introduces the subject by a text from the prophecy of Zechariah, chap. 4, ver. 14. “Then said he, these are the two anointed ones, that stand by the Lord of the whole earth.”

Of his analysis of this text, and his premises drawn from it, I will only observe here, that he makes it the foundation of his system, viz. That the gospel ministry, and civil magistracy, are not distinct governments, but component branches of one government. To this purpose, page 8, he says, “This universal dominion committed to him, (Christ) as it respects the human family, in its administrations, consists in two great branches, namely, the magistracy and the ministry.” As he afterwards more fully explains and applies this doctrine, I will take no further notice of it in this place, than just to observe one error in his statement. The church of Christ, and the gospel ministry are not, as the author says, committed to Christ. The gospel ministers are appointed to feed the church of Christ, which he hath purchased with his own blood. The church is his purchased possession. It is the body of Christ, of which believers are members. It is his kingdom, which is not of this world, &c. We read of the word of reconciliation, and a dispensation of the gospel of Christ, being committed to the ministers of Christ, as ambassadors from him; but not of the church being committed to him. It is his own house, in which Moses and the apostles were servants. It is not committed as a trust. It is, by virtue of union, his body, his spouse.

The real meaning of this text, on which the author erects such a visionary superstructure, I will offer in the words of the learned and judicious Scott, in his notes on the place.1

“The prophet was still ignorant of the meaning of the two olive-trees, especially of those branches from which the oil was immediately conveyed to the lamps; and on enquiry he learned, that they were the two anointed ones, which stood before the Lord of the whole earth. Zerubbabel and Joshua, the anointed ruler and high-priest of Judah, who stood before the Lord, and were his instruments in the work of the temple, were the anointed ones intended: but they were only types and shadows (as the temple itself was) of him that was to come. They therefore typified Christ, as anointed with the Holy Spirit without measure, to be the king and high-priest of the church, and to build, illuminate and sanctify the spiritual temple. As the anointed high-priest, he purchased those gifts by the sacrifice of himself; and through his intercession in heaven, they are communicated by him as the anointed king of his church. From the union of these two offices in his mysterious person, both God and man, this inexhaustible fulness of grace is derived and conferred. Thus the olive branches of themselves distil the golden oil through the two golden pipes into the bowl: and from his fulness all receive that grace which they require for their several places and services, through the means of grace, as the seven pipes fed the seven lamps of the candlestick. It is plain, that the candlestick is the Jewish church, both civil and religious; and the oil with which the lamps were supplied, is the Spirit of God: and is it not equally plain, that Zerubbabel and Joshua were in these transactions typical persons, types of Christ our king and high priest.” See also the venerable Henry to the same purpose.2

The vision was for the encouragement of the Jewish church and nation, then newly emerged out of captivity, and was suited to that symbolical oeconomy under which they were placed during the continuance of the theocracy, or immediate government of Jehovah, in another and more peculiar manner than other nations were, and which was to continue until Christ the antitype should come and fulfil all that was prefigured of him by that typical oeconomy, and introduce the new covenant, or gospel dispensation. When Israel was brought out of Egypt into the waste and howling wilderness, they were constituted a peculiar and holy nation. “And ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation.” Exod. xix. 6. This was the divine proposal; and after they had been ceremonially sanctified, and had heard the law of the ten commandments, which is a compend of the moral law of nature, pronounced with an audible voice, from the top of Sinai, with tremendously awful accompaniments, and had publicly announced their cordial acceptance of the divine proposal, the peculiar national covenant, whereby they were constituted in their national character, a kingdom of priests and a holy nation, was wrote in a book, and consecrated by the shedding of blood. See Exod. xxiv. and Heb. ix. 15. 22. Many ordinances were added to this covenant, which were received by Moses in the mount, and afterwards in the tabernacle, and all was again ratified about forty years after. See Deut. v. No permanent additions were afterwards made, except for the building of the temple instead of the tabernacle, (2 Sam. vii. 18.) and adding psalmody and music, both vocal and instrumental, to the stated worship, by express divine authority. 2 Chron. xxix. 25.

In this covenant, a standing, hereditary priesthood and numerous symbolical rites were added to the ancient sacrificial worship, as well as the sanction of temporal rewards and punishments, and the immediate divine presence in the sanctuary, to deliver oracles when sought in difficult cases, according to the due order; and a succession of prophets, until the great prophet should come with power to change the system, was engaged. A civil magistracy, of very limited authority, was instituted, and of a peculiar form. It was not sovereign; it had no legislative authority: and it is in this that sovereignty consists in all civil governments. They could not add to, or diminish from, the code of laws, without immediate divine authority. Even David, a king according to God’s heart, and a prophet by whom the Spirit of God spake, could not add stated singers and psalmody to the worship, but by special authority from God, delivered by other prophets. The civil government therefore, under this covenant, was wholly executive and judiciary; and in all important instances, connected with the priesthood, a decision in judgment could not be given in the last resort, except in a court where the priests and Levites were essential constituent members. They could not go to war without a priest to make the proclamation of the law, in that case provided. A leprosy could not be cured, a case of jealousy between a man and his wife could not be decided, nor uncertain murder expiated, but by the priest. The priests and Levites were the repositories of the laws—they were wrote in a book, and laid up with them. Even when it pleased God, after severely reproving them for the attempt, to tolerate them in having a king, the king was not permitted to exercise legislative authority; that is to say, to be a sovereign. He was directed to take a copy of the laws deposited with the priests and Levites; and he could not add to them. Though the Israelites held their lands in fee simple, to them and their heirs, they were not permitted to eat of the fruit of the fields or vineyard, until the priests had received their first fruits. In short, to use the words of the justly celebrated H. Witsius, D.D.3 speaking of the Jewish laws, “They were subservient, for the greatest part, to the levitical priesthood, with which almost the whole policy was interwoven.”

I admit that the reverend author might, without great impropriety, have said, that the magistracy and ministry, under the immediate government of God, viz. the peculiar theocracy of Israel, were two great branches of that symbolical government, if he had explained what he meaned by branches. He certainly could not wish to impose on his people so far, as to induce them to believe, that the word branches, thus applied, is a scriptural term. Under the Jewish polity, priests were instituted to conduct the symbolical worship, and to decide in courts of justice; whereas, in former times, every worshipper, such as Noah, Abraham, Job, &c. were priests for their own families. Melchizedec is the only person recorded, as by office, the priest of the most high God, before the institution of the Aaronic priesthood; and before that priesthood was established, Moses, the most eminent type of Christ, as mediator and lawgiver in his own house, acted the part of both priest, prophet and civil magistrate, and was a type of Christ in all his offices. But after this institution, the administration under Jehovah, their peculiar king, was distributed into different parts or portions, of which the priesthood took the highest hereditary rank, and the Levites the next; but wholly distinct in their offices, except that they were equally connected as constituent members in the supreme court of civil justice, and in being the official repositories of the laws.

Every city was enjoined to appoint local judges, from whose decision an appeal lay to the supreme court, composed of priests and Levites, assisted by such chief judge as Jehovah their king should appoint; which was sometimes a priest.

When kingly government was introduced, against the approving will of Jehovah their king, and of Samuel his prophet, they, as was expressly foretold by Samuel, became, in a great measure, despots, and usurped every power but that of the priests; and even from them the judiciary power in many cases, which was protected by the immediate divine interposition, as in the case of Uza and Uziah. Nor did the pious kings usurp the power of making laws. Zerubbabel, of the royal line of David, like his great ancestor, was honoured with being a very distinguished type of the Saviour. In the vision therefore, Joshua and Zerubbabel are very properly represented as types of Christ, in his priestly and kingly offices. Zerubbabel was the legal representative of Cyrus, king of Persia, at that time the sovereign of all the countries formerly subject to Babylon, as Ezra and Nehemiah afterwards were; and while he was honoured so far as to be the representative of the king of Persia, he was still more highly honoured with being proclaimed, by the prophet, a type of a greater than Cyrus, but whose kingdom was not of this world.

The author, surely, will not pretend that Zerubbabel, though of the stock and lineage of David, and the last of the royal race that enjoyed civil distinction, governed in right of hereditary succession from David. He was a subordinate and temporary governor, subject to the control of the governors on that side of the river, and the supreme direction of the king by whom he was appointed.

Artaxerxes, the most favourable to the Jews, for the greatest length of time, of all the Medio-Persian kings, (probably the same as Ahasuerus) appointed Ezra, a priest, to be governor of Judea; and after him, Nehemiah, once and again: both excellent appointments, but none of them of the royal line. In short; Zerubbabel, as the representative of Cyrus, in restoring the Jewish church and nation, which had been scattered abroad throughout all the nations of the east, was a very fit type of Christ, who came to restore and build up the dispersed tribes of Israel from all nations, tongues, and kindred. Melchizedec, who was a Gentile, and not after the order of Aaron, was selected as a very striking type of the Redeemer. Cyrus himself is selected by the prophet Isaiah, to prefigure the Saviour. “I have raised him up in righteousness, and I will direct all his ways: he shall build my city, and he shall let go my captives, not for price or reward.”—Isaiah iv. 15, &c. [Findley meant xlv. 13.]

I have heretofore believed, that it was generally admitted by christians, that the typical priesthood of Melchizedec, and the typical redemption wrought by the Medio-Persian kings, prefigured, and was a prelude to, the calling of the Gentiles. Surely, the reverend author will not pretend that Zerubbabel was the actually anointed king of Israel, or exercised sovereign power. Even Joshua could not have been anointed and inaugurated into the priesthood, according to the law of Moses, in the sanctuary, and with the holy oil. There was no sanctuary, and the Urim and Thummim, the fire which first descended from Heaven, the ark of the covenant, and other precious arcana, were lost; therefore the anointing of Joshua and Zerubbabel was not such a ceremonial anointing as that of Aaron, Saul, David, &c. but a providential designation to those offices, in such circumstances as rendered them suitable types of the Saviour. I may here be permitted to add that the loss of those precious arcana, the visible symbols of divine presence and glory, while it was an awful correction for the breach of the national covenant, indicated the final abrogation of that system, which, being only a shadow of good things to come, was seen to vanish away; and also prepared the minds of believers to expect the new covenant dispensation, foretold by the prophets, and the greater glory of the latter temple also foretold.

Though these two typical anointed ones represented the kingly and prophetical offices of the Saviour, they were not constituted such by the law of Moses. Cyrus was the sovereign, in a much more extensive sense of that term, than any king of Judah ever could have been under, or agreeable to, the Mosaic law. Zerubbabel was his honorary servant, acting under his instructions, and solely by his authority; and by the same authority, the progress of the work was stopped, and renewed, or suspended, viz. at the discretion of the Persian kings; so that the building of the city was not completed till about ninety years after the proclamation of Cyrus, and long after the death of Zerubbabel. I only add, in this place, that facts must not be permitted to bend to fanciful theories. Admitting, but not granting, that Zerubbabel had even sat on the regal throne of his great ancestors, David and Solomon, possessed of their independence and surrounded with all their splendour, it would have made no difference, as to the general argument, respecting civil government, as instituted under the moral law of nature. Every thing in the law of Moses, superadded to the moral law of nature, is positive or voluntary; and, therefore, changeable, according to circumstances and the will of the supreme legislator; and even while they continued, they were only applicable to the cases, place, and circumstances, for which they were intended and enacted. Their example may be further applied, but their authority cannot.

The reverend author has, throughout his whole book, made the support of the union of church and state, or, in other words, tyranny over both the souls and bodies of men, his grand object; and (very unwarrantably indeed) laid the foundation of his system on the symbolical text just examined. I have, therefore, on mature deliberation, thought it best to examine the nature and obligations of the peculiar law, or covenant of Israel, on all mankind, or on all christians, and at all times, before I proceed to other observations on his system.

As a clear and exact knowledge of the moral law of nature is peculiarly important, in order to understand the whole system of revealed religion, I will state, that it pleased God to deliver, on Mount Sinai, a compendium of this holy law, and to write it with his own hand, on durable tables of stone. This law, which is commonly called the ten commandments, or decalogue, has its foundation in the nature of God and of man, in the relation men bear to him, and to each other, and in the duties which result from those relations; and on this account it is immutable and universally obligatory. Though given in this manner to Israel, as the foundation of the national covenant, then about to be entered into, it demands obedience from all mankind, at all times, and in all conditions of life; and the whole world will finally be judged according to it, and to the opportunity they had of being acquainted with it, whether by reason and tradition alone, or by the light of the written word. This law is spiritual, reaching to the thoughts and intents of the heart. It is necessarily the foundation of all transactions, between the Creator and his rational creatures; and, in this case, was very properly revealed, as the foundation of the covenant of peculiarity with Israel. See Scott on Exod. xx. This was incorporated in the judicial law, as far as divine wisdom thought proper, and is explained and applied by the Saviour, and by the prophets and apostles.

There is an evident distinction between moral precepts, and positive or voluntary appointments. The first have their foundation in the nature of God and of man, and are unchangeable; the second in the free will of the lawgiver, and might not have been, or might have been otherwise, as the lawgiver thought proper, and are liable to be changed or abolished, at the discretion of the lawgiver; but while they continue, are of equal obligation with moral precepts, except where they come into competition: in that case, a positive institution must yield, in some cases, to the unchangeable law.

Of this kind were all the additions made to the moral law, by the Mosaic institutions. Yet it is upon these, almost exclusively, that the author builds his system; he substitutes them for the moral law; he makes little use of the prophets, and none of the New Testament, except to pervert it. The New Testament has been generally understood to contain the religion of Christians. The apostles declare, that the christian church is built on the foundation of the prophets and apostles, Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner stone; and that the law of peculiarity, old covenant, or testament, is abolished, taken out of the way, &c. The author declares that it is still in full force, as far as it is necessary to support his system, but not further: he admits the rest to have been abolished. Christ himself has given the most excellent summary of the moral law, and the most spiritual and perfect exposition of it, and declared its perpetual obligation. The apostles have incorporated the ten commandments into their epistles, and enforced their obligations by the most powerful arguments and motives; but neither the Saviour nor his apostles have made any use of the law of peculiarity, except to shew that its requirements were fulfilled, and that it was abolished, except in a few instances, for illustration. The apostles no where enforce obedience to its peculiar precepts or penalties, after it was abolished by the death of Christ, but declare it to be disannulled.

Positive or voluntary laws have no obligation, further than the lawgiver intended that they should have, because all the authority they possess, is derived from his will and intention; where this stops, the law must stop with it. Now the intention of the Sinai covenant does not appear to have extended beyond the Israelites themselves; it was addressed solely to them, and calculated to operate within bounds expressly prescribed, and could not be put in operation elsewhere. It is sanctioned with numerous and severe temporal penalties, several of which were to be executed by the civil magistrate and the witnesses, after the sentence of the court, and some of them by Jehovah himself, as their peculiar king; and obedience to it was encouraged by numerous temporal rewards, and by miraculous protection. They were assured of success in war, of fruitful seasons, that nothing should cast their young, or be barren among them, &c. &c.

The moral law was addressed equally to all men in their individual character, and in the singular number: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me”—“Thou shalt not make unto thee graven images”—“Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain”—“Honour thy father and thy mother,” &c. The lawgiver also reserves the sanctions, or rewards and punishments of this law, solely in his own hand. “I will not hold him guiltless”—“I will visit the iniquity,” &c. “Thy days shall be long,” &c. This law required the obedience of the heart, with a view to a judgment to come; but a fulfilling of the letter of the law satisfied the national covenant—it only required circumcision of the flesh; the moral law required circumcision of the heart. This distinction the prophets, the faithful expounders and zealous enforcers of obedience to the moral law, frequently inculcated. The Pharisees were zealous of the law, but added their own traditions. The Sadducees were zealous of the law, and opposed the traditions. Both of them were characterised, by the Saviour, as very immoral and erroneous; yet neither of them could be excluded from communion, under that law.

The penalties enacted by the national law could only be executed within the bounds prescribed—Numbers, chap. xxxiv. Within these bounds, idolatry was not only a sin, as in other places, but it was, if committed by an apostate Israelite, treason against Jehovah, as their peculiar king. The iniquity of the devoted nations being full, they were to be destroyed; but no authority was given to punish idolatry out of those limits, nor even to carry their own worship out of the typically holy land. In their dispersions, they taught the law in their synagogues; but do not, till this day, put in practice the worship enjoined by the law of Moses—the place being an essential part of the institution.

The moral law is equally calculated for, and applied to, all persons, in all places, and at all times; and equally authorizes the worship of God, in all places, by all men, in all situations; and enjoined a respect to every discovery of his will, and institution of his appointment: but it prescribes no penalties to be executed by man for the breaches of it. None but God, that knows the heart, can judge of the demerit of sin; because it does not consist so much in the physical act, as in the will and intention, of which none but God is judge. Fallible judges must have recourse to overt acts, declarations and circumstances, to prove the concurrence of the will, or intention of the heart, and may be often mistaken. The innocent may sometimes suffer, but the guilty more frequently escape punishment. God only is the unerring judge.

This being the case, it follows of course, that human penalties for breaches of the moral law, are no part of that law itself, as it relates to God; he will not give this glory to another—nor is any creature, man or angel, competent for the exercise of it.

Penalties to be executed by men upon their fellow men, arise from the state of society, they being necessary for the peace and happiness thereof; they, therefore, vary in every society, agreeable to the circumstances of the society itself, and the prevalence of vices, by which its safety is most exposed to danger, or upon its competency to execute such penalties.

In a state of nature, before the existence of civil society, no such penalties could have been executed; every man’s rights were equal. Men being, after the first pair, introduced by natural generation, parental authority was sufficient, until they became capable to act for themselves. After this period, we know, by the awful example of Cain killing Abel his brother, that it was not sufficient. We know, likewise, by the same example, that no human penalties for crimes against society then existed: indeed it was not sufficiently numerous to enact laws or execute penalties; therefore God took the case of the infant state of society into his own hand, and inflicted such punishment of the murderer as he judged suitable to that state of society, but spared and protected his life; yet, for the safety of others, set a mark on him, and banished him; or, from the influence of fear, he banished himself. When men multiplied on the earth, oppression and other crimes prevailed to so great a degree, as to have rendered human laws and penalties very necessary; but how far such were enacted or executed, we are not informed. The degeneracy, however, being so great as to be incurable by ordinary means, it pleased God, in an extraordinary manner, to inflict the penalty of death on the whole human race, with the exception of one family.

In this second infant state of the human race, too few in number to form a civil society, capable of enacting and executing penal laws, it pleased God himself, among other precepts, to prescribe death to be inflicted by man, as the penalty for murder; and as there were not, at that period, civil courts, or officers for public prosecution, he enjoined the brothers (explained to include others near of kin) of the deceased, to execute the sentence, under the penalty of God himself requiring his brother’s blood at his hands, as he had formerly done the blood of Abel at the hand of Cain. This precept, given to the family of Noah, then containing the whole human race, is still in substance equally applicable to all nations, and at all times. It is the only punishment adequate to the offence; but the appointment of the brother, or near of kin, to be the avenger of blood, arose from the then state of society, and pointed out the expediency of civil government, when men became sufficiently numerous for that purpose. The avenger of blood would not distinguish sufficiently between the different kinds of homicides; and this would produce other revenges, as it still does where it is practised, and did in the feudal times in Europe, while the heads of families or clans exercised the right of avenging their own wrongs, or that of their relations, and increased the shedding of human blood.

Before the death of Noah, and long before the death of Shem, we find numerous civil societies were instituted in comparatively small territories; that property was divided; and that, consequently, life and property and civil order were protected. The division of languages, about 101 years after the flood, necessarily promoted the division and settling of the earth by small civil societies. We find them very numerous in the days of Abraham, 433 years after the flood, and while Shem was yet alive.

About 857 years after the flood, when it pleased God to constitute the Israelitish branch of the family of Abraham, (to whom he had long afforded special protection, and given special promises) a distinct nation, and to become their peculiar King, and give them a code of laws peculiar to themselves as a nation and government, distinguished from all the nations of the earth; he having, after long striving with them, determined to give up the rest of the world, in a great degree, to ignorance, idolatry and licentiousness, and to wink at the prevalence of these evils till the desire of all nations should come, this church and nation, (for both were one, and all were symbolically holy) was the repository of the lively oracles, first given by Moses, and continued in the sanctuary, or added by the prophets, till Christ came. This church and nation were to keep up a testimony against the prevailing idolatry of the world, but not to overturn or suppress that idolatry, except within their own territory. But to preserve them from the prevailing contagion of idolatry, their peculiar laws were calculated to prevent their communion with the nations around them, not only in their religion, but in their manners, their marriages, their clothing, their ploughing, sowing and reaping, and in the preparation, and in many instances, in the substance, of their daily food. They could not so much as eat with those of other nations.

In this peculiar code of laws, the precepts given to Noah were adopted; but the penalty respecting murder was revised. The power of the avenger of blood was not abolished, but modified. Courts of justice were erected to decide between wilful murder, with malice aforethought, and less criminal or innocent homicides, and cities of refuge provided. The master who killed his servant, whether wilfully or not, was, for some special reasons, exempted from the power of the avenger of blood, or from being banished to the city of refuge. There were no servants or slaves when the precepts were given to Noah. We are not well informed how this law was construed in the execution; but when the government was permitted to be so far changed as to have hereditary kings, we know that the best of these kings dispensed with the punishment of murder. David dispensed with it in the case of Absalom, and also in the case of Joab in two instances; all of them wilful and malicious. It pleased Jehovah himself, as King of Israel, to dispense with, or change, the punishment of murder and adultery, in the very aggravated case of David and Uriah. Joab was afterwards put to death by Solomon for treason, as Shemei also afterwards was, without any hearing or trial before a court of justice, as enjoined by the law of Moses. And Abiether, in the same manner, thrust out of the priest’s office.

The above examples contribute to demonstrate, that temporal penalties, to be executed by fallen man on his fellow sinners, are no part of the moral law of nature. If they were, they could not be dispensed with or changed: for the essential character of the moral law is immutability; it is unchangeable like God its author, a transcript of whose divine perfections it is. The sum of this law is declared by an infallible interpreter to be, To love the Lord our God with all our heart, &c. and to love our neighbours as ourselves. This law never was, nor ever will be, changed, mitigated or dispensed with. It never can yield to policy or expediency. If it could have done so, the martyrs, who loved not their lives even unto the death for Christ, were fools. That martyrs died for positive institutions, arose from the authority of the moral law, obliging to obey them.

It may be objected, that the conduct of David and Solomon, in the instances above mentioned, was probably wrong, therefore not suitable precedents to follow. They are not only not censured in scripture, but David is expressly justified in all his conduct as king, except in the case of Uriah. He is also justified in using the shew-bread, equally contrary to that law, by Jesus himself, the most perfect judge of the relative obligation of laws. Positive laws in their own nature, must yield to more powerful laws; therefore, are changeable agreeable to circumstances. No one code of penal laws can apply equally to all nations, at all times.

When Judge Blackstone wrote on the laws of England, there were 162 penalties of death.4 The Judge laments the number, and the impropriety of many of them. The change of manners, modes of life, and property, require a change of penal laws. In Scotland, though part of the same island, and subject to the same king and parliament, there are not that number of penal laws; nor are there as many capitally convicted there in one year, as in the county of Middlesex, which contains the city of London. In all the seventeen United States, the criminal laws vary less or more from each other. In all of them they are less sanguinary than generally in the nations of Europe. In Pennsylvania they are less so, perhaps, than under any other civilized government; and in no government is the public peace better preserved. But this improvement in favour of humanity could not have been accomplished, if the legislature of that state had not been in a capacity, and willing to be at the expense of providing a suitable prison, labour, workshops, &c. for those who, under other governments, would have been hanged. By this wise institution, human blood is spared, the criminals are well clothed and fed, and contribute to their own support, while society is protected from their depredations. Thus, by the laws of that state, the detestation of shedding human blood, so laudably and strongly expressed in the precept to the sons of Noah, and in the law of Moses, is more strongly and effectually provided against than could have been done in the early stages of society, when there was yet not the means of establishing and supporting the criminal code of Pennsylvania, which provides for putting the wilful, malicious murderer to death, and preventing the effusion of human blood, by otherwise securing such other criminals as were put to death under the former government, and still are put to death under other governments.

The penalties of the judicial law were not of moral and universal obligation, because they were not from the beginning. Sixteen hundred and fifty six years had passed away, before the precepts were given to Noah that were equally applicable to all mankind; and 2513 years, before the Israelitish Theocracy was instituted; which only continued to operate in a small territory, during 1491 years; and never was applied to, or intended for, other nations. It could not be administered, but at the place, and by the judges, appointed by God, as the peculiar king of Israel.

The moral law of nature was the same before man revolted from God, that it was afterwards; and will continue to be the same for ever. There was no place or use for temporal penalties to be inflicted by man on his fellow men, before that revolt: consequently, they are not the moral law, but were necessarily introduced because of transgression, for the protection of civil society, that men might be enabled to live peaceable lives, in godliness and honesty. It was for this purpose that men instituted civil government itself, agreeable to the will of God; and hence it is, that penal laws are not made for the righteous man, but for the lawless and disobedient.

The law of nature consists of the eternal and immutable principles of justice, as they existed in the nature and relation of things, antecedent to any positive precept; and describes the immutable principles of good and evil, to which the Creator himself, in all his dispensations, conforms; and which he has enabled human reason to discover, so far as they are necessary for the conduct of human actions—such, among others, as these principles: that we should live honestly, hurt no body, and render to every one his due. And he has, in the usual course of his dispensations, made it our interest to pursue this line of conduct, so far as that our self-love comes frequently in aid of our duty.

The law of nature being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is of course superior to, and the foundation of, all other laws. It is binding all over the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if they are contrary to it; and such of them as are of any validity, derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from their original: but it is necessary to exercise human reason in the application of the laws of nature to particular cases. If our reason was always, as in our first ancestor before his transgression, clear and perfect, unruffled by passions, and unclouded by prejudice, we should need no other guide but this: but every man now finds the contrary in his own experience—that his reason is corrupt, and his understanding full of ignorance and error.

This state of things has given manifold occasions for the benign interposition of Divine Providence, by which God, in compassion to the frailty, the imperfection, and the blindness of human reason, hath been pleased at sundry times, and in divers manners, to enforce his laws by immediate and direct revelation. The doctrines thus delivered, Christians call the revealed divine law, and they are to be found only in the holy scriptures. A law made by man, or penal laws to be executed by man, could have no application to men individually, in a state of nature; because the law-making power is always in such as possess supreme authority over organized society. Men in a state of nature are all equals: but man never existed long in that state. The elder brother murdering the younger, while in that state, was an awful lesson in favour of union in a state of civil society, able to afford protection to its component parts. From the fears, the wants, and the crimes of individuals, civil society originated; and from the same source has it been supported, throughout all successive ages. Anarchy has never appeared but with such destruction in its train, as soon obliged men to resort to civil society for protection. Numerous examples of this have been produced in our own day: so that it is a settled maxim, both with expositors of the bible, and politicians, that even a bad government is better than none.

It is universally admitted, I presume, that it is the will of God that all his reasonable creatures should pursue their own happiness, in a way consistent with the happiness of creatures of the same common nature; and that this is, in so far, the moral law of nature. Men must first associate together, before they can form rules for their civil government—When those rules are formed, and put in operation, they have become a civil society, or organized government. For this purpose, some rights of individuals must have been given up to the society, but repaid many fold by the protection of life, liberty and property, afforded by the strong arm of civil government. This progress to human happiness being agreeable to the will of God, who loves and commands order, is the ordinance of God mentioned by the apostle Paul: and being instituted by men, in the exercise of their natural reason, for their protection, it is the ordinance of man, and as such to be obeyed, as mentioned by the apostle Peter.

After the call of Abraham, and the gracious manifestation of the covenant of grace to him, he and his family enjoyed the special protection of God, and communications from him. This gracious dispensation accompanied the promised seed, viz. Isaac and Jacob; who, with the name of Israel and his family, enjoyed the blessing and promised protection. They enjoyed it, when in the house of bondage in Egypt. Even during this horrid slavery, they preserved the order of their tribes, and had their elders, or heads of families. The name elder is of Egyptian origin—The first we hear of it is in Gen. l. 7.; but it came to be much used in Israel. It was the elders of Israel that Moses addressed by the commandment of God, when he returned to Egypt; but they had no magisterial or judicial authority. Moses was the first and only magistrate, until subordinate magistrates were appointed agreeable to the advice of Jethro. When the Sinai covenant was made, a permanent magistracy was established, of which the priests and Levites were constituent members.

Preparatory to the Sinai covenant, the people voluntarily engaged to obey all that the Lord had spoken, after having received the promise of being thereupon constituted a peculiar nation. See Exod. xix. The next preparatory step was the giving of the ten commandments, viz. a transcript of the moral law of their nature; which, as it equally related to all mankind, was delivered with an audible voice, from the top of a mountain, with such tremendously glorious and awful accompaniments, as testified the presence of God omnipotent. This law was also wrote by the finger of God, on tables of stone—a fit emblem of its unchangeable perpetuity. This the people engaged by covenant to obey, as God had commanded them. See Deut. iv. 13. Thus, under the immediate divine direction, they formed a society before they became an organized body politic.

These solemn preparations being made, it pleased God to propose the terms of the covenant of peculiarity, whereby Israel was constituted a nation separate and distinct from all other nations. Rules whereby their courts of justice and magistrates were to be guided in deciding on crimes, damages, &c. were prescribed. Exod. xxi. 23. In the 24th chapter, Moses declares these laws to the people, who answered with one voice, and said, all the words which the Lord hath said we will do. Moses wrote all the words of the Lord, and rose up early, &c. Next follows the solemn consecration of the national, commonly called the Sinai covenant, or law of peculiarity, because it originated at Sinai, and was only applicable to Israel. The law of the ten commandments was an abstract of the moral law of nature, which was from the beginning, and is equally applicable to all mankind.

The typical consecration described in this chapter, as ratifying the Sinai covenant, is mentioned in the epistle to the Hebrews, when the apostle is demonstrating the abrogation of the Sinai covenant, and the introduction of the new covenant, viz. the gospel dispensation. Heb. ix. after shewing that the consecration of the Sinai covenant with blood, typified the death of Christ, for the remission of sins, by his own blood, he states the consecration of the Sinai covenant as emblematical of the blood of the new testament, by which Christ put away sin by the sacrifice of himself. He says, in chap. x. 9. “Then said he, Lo, I come to do thy will, O God.” He taketh away the first, (viz. the first covenant) that he may establish the second, (viz. the second covenant, or gospel dispensation) which took place of the old covenant or testament. See Heb. ix. 18. In the 8th chapter, the apostle appeals to the prophet Jeremiah, for proof of the abolition of the Sinai covenant, who testifies that the new covenant is not according to the covenant made with their fathers, viz. the Sinai covenant, made when he brought them out of Egypt. The apostle argues from the prophet, that, in that he saith a new covenant, he hath made the first old. Now that which decayeth and waxeth old, is ready to vanish away; and in Gal. iii. 17. the same apostle, speaking of the covenant of grace, that was confirmed to Abraham by God in Christ, the law, (viz. the Sinai covenant) which was 430 years after, cannot disannul it; and Eph. ii. 15. speaking of what Christ has done by his death, he says, “having abolished in his flesh the law of commandments contained in ordinances;” and thus, as he says in the former verse, “he hath made both Jew and gentile one, by breaking down the middle wall of partition between them.”

Proofs, to the same purpose, from the prophets and apostles, might be multiplied, were it necessary; but I will only add one from the evangelists—John i. 17. “For the law came by Moses, but grace and truth came by Jesus Christ.” For a further contrast between the old and new covenants, I refer to Deut. xviii. 15, 19. and to Ezekiel xvi. 6, 62. In all these scriptures, and more that might be named, the Sinai covenant is abolished; not in part, but wholly abrogated, disannulled, &c. If, therefore, the Scriptures tell truth, no part of it remains obligatory on christians; and those who maintain it to be so, act, in so far, in direct opposition to the prophets, the evangelists, and apostles. This is confirmed by approved commentators.

The learned Scott, on Exodus xxiv. 3, 4. says, “When Moses had set before the people the substance of the judicial law, which he had received with the moral law of the ten commandments, delivered from mount Sinai; and the promises made to them of special blessings, while obedient; they unanimously and willingly consented and engaged to be obedient. Accordingly, he wrote in a book, the four foregoing chapters, as the conditions of the national covenant, which was now about to be solemnly ratified. For such it certainly was: seeing that the covenant of works has nothing to do with altars, sacrifices, and the sprinkling of blood, and the covenant of grace is not made with whole nations, or collective bodies of divers characters, but only representatively with Christ, as the surety of the elect, and personally with true believers. But whilst this covenant was made with the nation of Israel, in respect to their outward blessings, it was a shadow of good things to come.”

That this covenant was abrogated, when the intention, for which it was instituted, was accomplished, is stated by the same judicious author, in his comment on Jeremiah xxxi. 31–34. “The national covenant,” made at Sinai with Israel, when brought out of Egypt, is here contrasted with “the new covenant.” Notwithstanding the tender and compassionate love of Jehovah to Israel at that time, when he espoused the nation to himself, they proved unfaithful, and broke the covenant, by apostacy, idolatry, and iniquity; and at length, by rejecting the Messias, they were cast out of the church, and expelled from the promised land. This covenant was distinct, both from the covenant of works, of which Adam was the surety, and under which, every unbeliever, in every age and nation, is bound; and from the covenant of grace, mediated by Christ, of which every believing Israelite received the blessing. This promise of a new covenant, as St. Paul hath shewn, implied the abrogation of the Mosaic law, and the introduction of another and more spiritual dispensation. See the same learned author on Heb. viii. Also on Zech. xiv. 4, 5. where he says, “In consequence of his (Christ’s) ascension, and the commission granted to his apostles, the gospel was sent to the different regions of the earth. The ceremonial law, and the whole Mosaic dispensation, which obstructed the admission of the gentiles into the church, as the surrounding mountains did their entrance into Jerusalem, were removed.”

On the prophecy of Haggai ii. 69. the author says, “Then the Lord would shake the heavens and the earth, &c. Various convulsions and changes would take place in the Jewish church and state, which would end in abolishing the ritual and whole Mosaic dispensation, the disannulling of the national covenant, the subversion of their constitution, the destruction of Jerusalem, and the ruin of their civil government.” See also the venerable Henry to the same purpose, on the above and similar texts, in both the old and new testaments. I know of no approved commentators, but what are in unison with the above.

That this covenant, or national constitution, was local, viz. confined to a particular country, is evident through the whole transaction. The devoted nations are expressly described in different places, and the geographical boundaries defined with precision, Num. xxxiv. 1–15. and the administration of the national law expressly limited to the land within those boundaries. Deut. iv. 14. “And the Lord commanded me at that time to teach you statutes and judgments, that you might do them in the land whither you go over to possess it.”

The time meant was after giving the moral law as the foundation of the Sinai covenant, containing these statutes and judgments. The land was that of the devoted nations, which they were going over to possess. Those statutes and judgments were not to be administered in other lands. Through their own fault, even those nations were never all subdued or possessed. They never possessed the land of the Philistines, nor the Sidonians. Though David at last overcame the former, he did not dispossess them. Edam, Moab and Ammon, adjoining Arabia and the Red Sea, Syria of Zaba, and Damascus, extending from Palestine to the Euphrates, were subdued by David; and they, as well as Arabia on the south, yielded a willing obedience to Solomon, thereby fulfilling the promise to him, as a type of the Messiah, that his large and great dominion should extend from the Mediterranean, then called the Great Sea, to the great river Euphrates on the east, and to the Southern Ocean, from near which the queen of Sheba came, and beyond which there is no continent; emblematical of the kingdom of the Messiah, to extend over the whole world. This, however, was a dominion of peace. The people were not dispossessed, nor brought under the national law of Israel—it could not be administered there. This is the opinion, and agreeable to the practice of the Jews in Babylon, and in their dispersions, to this day. The schismatic Jews, who erected a temple in Egypt, and those who erected another at Samaria, did so in direct violation of the Sinai covenant.

Mr. Wylie, page 23, states, that “it is the magistrate’s duty to execute such penalties of the divine law, (meaning the peculiar law of Israel) as are not repealed or mitigated;” and several years ago, an intelligent and pious gentleman sent me a copy of a manuscript volume, of thirty one folio pages, very closely written, entitled “Observations concerning Toleration,” in which he adopts and supports the same principles respecting divine laws, &c. that are advocated in the Sons of Oil. From it I will now insert the following quotation, p. 3. “I plead—the laws and examples of the Jewish nation, and that upon this ground, that all the laws and precepts contained in the Old Testament, that are not repealed in the New, either by express precept, approven example, or by necessary consequence, are still binding—a law being once given, until it is repealed by the same authority, is still binding.”

The above is so much less exceptionable than the Sons of Oil, that it does not include the idea of mitigating divine laws. Where either of them got the idea of repealing or mitigating divine laws, they have not informed us; certainly, however, they did not get it in their bible. It is necessary that imperfect and short-sighted men should repeal or revise their laws. Revision is a repeal in part; but to apply the term mitigation to laws, whether human or divine, is a near approach to nonsense. In most governments, provision is made for mitigating the sentence of a court, arising from the law and the fact, or for remitting the sentence wholly. Thus, in England; the king frequently mitigates the sentence of death, by substituting transportation and servitude, or pardons, either with or without conditions; but neither repealing nor mitigating can be applied to any law of God, without an approach to blasphemy.

That none of these can apply to the moral law of nature, it being unchangeable, has been already stated; nor can it be maintained, without, at the same time, maintaining, that God himself is changeable. They cannot be applied to positive or voluntary laws, without admitting that the Almighty was short-sighted, like fallen mortals; that he did not know the end from the beginning; that causes, or changes, had taken place, which he had not foreseen, when he made the law, which rendered the future repeal or revision necessary. These are the causes why human laws are repealed or revised. I never read of a law for the mitigation of a law, but in the Sons of Oil. Positive laws have frequently been passed for special and local purposes, that ceased when the purposes were accomplished for which the legislature intended them; several of these I have mentioned already. I will only add, that the laws regulating the march of Israel in the wilderness, the gathering of the manna, &c. the command to the disciples, by the Saviour, when he sent them out to preach the gospel and work miracles, not to go to the cities of the Gentiles or the Samaritans—ceased, when the object intended was accomplished; so did the whole additions to the moral law, contained in the Sinai covenant of peculiarity, when their object was accomplished, and the intention of the legislator fulfilled. They ceased, or were abrogated, but not repealed or mitigated.

Divines have very commonly, for the sake of illustration, spoken of the peculiar law of Israel, under two distinct views, viz. as ceremonial, enjoining and regulating religious rites, and as judicial, regulating the courts of justice, &c. This distinction is often made without any injury to the subject; but having no foundation in the law itself, a precise line of distinction cannot be drawn. The learned Dr. Witsius has well stated, after an accurate examination, that all their polity was so connected with priests and Levites, that no such precise line could be drawn. The reverend author of the Sons of Oil, though he builds his system on this distinction, has not condescended to mark the line. The author of the manuscript has been more candid. He says, p. 9. “The ceremonial law was a system of positive precepts about the external worship of God, chiefly designed to typify Christ as then to come, and to lead to the way of salvation through him. The judicial law was that body of laws, given by God, for the government of the Jews, partly founded on the law of nature, and partly respected them as a nation distinct from all others. The first respected them as a church, the second respected them as a nation, distinct from all others. This distinction is so easy understood, that it will require a great deal more than what I have yet seen to overthrow it.”

The author has been candid enough not to lay the support of this distinction on the scriptures, where, indeed, he could not find it, but gives it as “he finds it stated by authors.” And it is as well defined as is desirable; for it is, as he says, easy understood, which is the excellence of a definition; its only loss is, that it is not supported by scripture, and is impracticable. It puts me in mind of the theories of the creation of the earth, published by Whiston, Burnet, Buffon, &c.5 They all tell a very pretty story of how they would have made the earth, and, therefore, how God should have done it. But they all differ in opinion from each other, how they would have made the world, but agree in objecting to the method in which it actually pleased God to create it. Just so it is with those, who idolize, and attempt to reduce to practice, among christians, the peculiar law of the Israelitish theocracy, which has been fulfilled and abolished by its divine author. They all claim the authority of that law to patronize their own opinion, or justify their tyranny; yet none of them pretend to revive and execute the whole of that law; but though they all have miserably perverted it in their application of it, yet they have never agreed on defining how far it is applicable to christians, and how far not. How then shall the weak christian know, which of its precepts he is obliged to obey, and which to refuse—all of them being equally divine laws. The definition of the author of the manuscript, which I admit to be one of the best, he will himself, upon trial, find to be wholly impracticable, because it leaves it wholly to the private judgment of every christian to decide, what precept respected Israel, as a church, and what respected it, as a nation, distinct from all others. If applying this rule to all particular precepts was too difficult a task for the author of the manuscript, or of the Sons of Oil, what must it be to weak but well meaning christians. The difficulty to them must be the greater, from the circumstance, that the New Testament, which contains the religion of christians, having declared that this law is wholly abolished, has given no directions for making a discrimination of its precepts.

Divine wisdom has so intimately connected those precepts together, that they could not be separated. They, as a system, being the symbol or type of the New Testament church, were, like it, one body with many members. To this the whole language in scripture, applied to this institution, agrees that Israel was a holy nation, a kingdom of priests, a peculiar people, all ritually sanctified and holy; their kings were equally types of the Saviour, as their priests were. Mount Zion, the city of the king, was equally typical, as Mount Moriah, where the temple stood; the land was holy and symbolical of the heavenly rest. Joshua, the chief magistrate and military commander, who introduced Israel into the land, was an illustrious type of the Saviour, in that very act. The author must mark out his line of discrimination more distinctly, before he can build a system on it. For illustration, it may do well enough, if not carried too far; but it is always to be kept in mind, that it is without foundation in scripture; neither prophets nor apostles have made it.

On examining the law itself, we find it composed of a number of different ordinances, each of them called a law, such as the law of the trespass offering, the law of the meat offering, the law of the passover, and the law for leprosy, &c. but when they are spoken of as a system or code, all are mentioned as one law; there are no such expressions to be found in the Old or New Testament, as the ceremonial law, or the judicial law; all are thus intimately mixed and connected together, as if done on purpose to prevent separating what God had so joined together.

I have not slightly examined this question, to support an argument, but strictly for edification: and I find the law of Moses above fifty times expressly named or alluded to in the Old Testament, and as often, at least, in the New Testament, always as one law, and in no place with the distinction of judicial and ceremonial laws. The distinction, however, between moral and positive laws, is easily traced: but I agree with Dr. Owen,6 in his saying, that Christ in fulfilling all righteousness in the room and place of sinners, fulfilled every law that man had broken.

That I am not singular in rejecting this distinction, it might be sufficient to state, that neither the Saviour, nor his apostles, have made it. But it is also rejected by human authorities of the highest character, as the most able advocates of the truth of the christian religion. I shall only in this place insert a quotation from Locke, whose name, along with Bacon, Boyle, Newton and Addison, is the boast of christians, in opposition to the unfounded boasts of deists, claiming learning and talents, as belonging to their ranks.7 Those great men, while they opened the gates of science to Europe, or demonstrated the extent and use of human reason, were at the same time, the ablest advocates for the truth of christianity, and set the brightest example of its power on the heart and life.

Locke says, “the law of Moses is not obligatory upon christians. There is nothing more frivolous than that common distinction of moral, judicial and ceremonial law. No positive law can oblige any but those on whom it was enjoined. ‘Hear, O Israel,’ &c. restrains the obligation of the law to that people.—By a mistake of both Christians and Mahometans, it has been applied to other nations. The Israelitish nation themselves never did so, nor do the dispersed Israelites yet do so.”

Though the Westminster divines make the distinction, they state it in such a manner, as perfectly to agree with the above.8 Chap. xix. after stating, that the law of nature was revealed in the ten commandments, delivered by God on Sinai, they say, sect. 3. “Besides this law, commonly called moral, God was pleased to give to the people of Israel, as a church, under age, ceremonial laws, containing several typical ordinances; partly of worship, prefiguring Christ, his graces, actions, sufferings, and benefits; and partly, holding forth instructions of moral duties. All which ceremonial laws are now abrogated under the new testament.” Sect. 4. “To them also, as a body politic, he gave sundry judicial laws, which expired together with the state of that people, not obliging any other now, further than the general equity thereof may require.” The general equity of this, or any system, is in so far, the moral law; which, in the next section, those divines declare binds all men for ever.

Thus, those venerable divines agree, with Locke and the apostles in opinion, that Christians are wholly set free from, the law of Moses, or peculiar law of Israel; and this opinion was adopted by the church of Scotland, in what has been reputed her purest times; and is still the opinion of all the now divided branches of the Presbyterian, and also of the Independent, churches, who adhere to the Westminster Confession.

Among the very numerous and respectable authorities, that might be added, I insert the following extracts from the very learned, orthodox and pious Dr. Witsius, in his oeconomy of the divine covenants.

In his first volume, the author shews that the moral law was unchangeable, and that it was the foundation of all God’s other solemn transactions with fallen men, and totally distinct from positive or voluntary laws, which had relation to men as fallen. In vol. 3, chap. 14. entitled Of the abrogation of the Old Testament, meaning thereby, as the apostles did, Heb. ix. 18–20. the Sinai covenant, consecrated with blood, typical of the New Testament, purchased with the blood of Jesus, the testator of the new testament, for the redemption of transgressors, but not including the prophets, &c. which we, perhaps improperly, call the old testament. The Saviour and the apostles called them the Scriptures. It is to be noticed, that he also spoke of the Sinai covenant wholly as ceremonial; because all the civil administration of it was so intimately interwoven with the ritual, that it could not exist without it; and because all was contrived so as to be a shadow of good things to come. These observations are necessary for the right understanding of the following extracts:

“To begin with the first: The foundation of the moral laws, whose perpetuity and unchangeableness is unquestionable truth, is of quite a different nature from the ceremonial institutions, as appears from the following considerations: Because the former are founded on the natural and immutable holiness of God, which cannot but be the examples to rational creatures, and therefore cannot be abolished, without abolishing the image of God: but the latter are founded on the free and arbitrary will of the lawgiver; and, therefore, only good because he commanded; and consequently, according to the different nature of times, may be either prescribed, or otherwise—prescribed or not prescribed at all. This distinction was not unknown to the Jewish doctors,” &c. p. 320. v. 3.

“But let us proceed to the second head, namely, that God intended they should cease in their appointed time. This is evident from the following arguments: First, the very institution of the ceremonies leads to this: for since they were given to one people, with limitations to their particular state, country, city and temple; the legislator never intended, that they should be binding on all, whom he favours with saving communion with himself, and at all times and in all places. But this was really the case. And the Jews have always boasted of this, that the body of the Mosaic law was only given to their nation, even to the inheritance of the congregation of Jacob, Deut. xxxiii. 4. and God confined it to their generations, Gen. xvii. 7. Lev. vii. 36. and xxiv. 3. But as their generations are now confounded, and the Levites by no certain marks can be distinguished from other tribes, or the descendents of Aaron from other Levites; it follows, that the law ceases, that was confined to the distinction of generations, which almost all depended on the tribe of Levi, and the family of the priests. God also appointed a certain country for the observation of the ceremonies. Deut. iv. 14. vi. 1. and xi. 31, 32.” p. 323.

The learned author, after shewing at large the typical consecration of the Sinai covenant, and writing it in a perishable book, distinct from the moral law wrote on tables of stone, in reply to such as, with Mr. Wylie, maintain that part of it remains binding on Christians, viz. what is not expressly repealed or mitigated in the new testament, observes,

“From these things, however, it is easy to conclude, that the new covenant was not promised to stand together with the old, and be superadded to supply its defects; but to come in place of the former, when that, as obscure and typical, should be entirely removed; which is plain from the words, Not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers, &c. In that he saith a new covenant, he hath made the first old: now that which decayeth and waxeth old, is ready to vanish away. Heb. viii. 13.”

In answer to the objection, that it does not necessarily follow, that the mention of a new covenant altogether removes the old, &c. he says,

“It is begging the question. A direct contradiction to God’s word. God says, I will make a new covenant, not like the former, which was made void. Men venture to answer, It is not an establishment of a new covenant, but a repetition of the old; and so far confirms the old. Yet, at the same time, this was its abrogation. We say, here is no promise of a new law, because none can be better or more perfect than that of the ten commandments. The new covenant is opposed to the old covenant, and is substituted in its place, and completes it, so as likewise, as we have shewn, to put an end to it.” p. 236, 237.

“The laws of the covenant, of which the ark was the symbol, were not only the ten commandments, but all the laws of Moses: accordingly, the book which contained them was placed in the side of the ark. That symbol, therefore, of the covenant, being thus abolished, both the covenant itself, and the laws, as far as they comprised the condition of that covenant, are abrogated. The case of the laws of the decalogue is different from the rest: for they were engraven on tables of stone, and laid up in the ark, to represent that they were to be the perpetual rule of holiness, and perpetually to be kept in the heart, both of the Messiah and his mystical body: while the others were only written on paper or parchment, and placed in the sides of the ark; seeing their being engraven on stone, and kept in the ark, signified their indelible inscription on, and continual preservation in, the hearts of believers.” p. 342.

The learned doctor, treating of the benefits of the new testament or covenant, and abrogation of the old, says, “Immunity from the forensic or judicial laws of the Israelites, not as they were of universal, (moral law) but of particular right or obligation, made for the Jews, as such, distinguishing them from other nations, adapted to the genius of the people and country, and subservient, for the greatest part, to the levitical priesthood, with which almost the whole polity was interwoven.” p. 370.

In page 7, Mr. Wylie proves, in several premises, that all moral, physical, and delegated power, &c. is necessarily and independently in God, and that all should be done for his glory. This, none but atheists, if there are such, deny. Practical atheists, who live as if there were no God, are numerous; but atheists in theory, I never was personally acquainted with. Many, indeed, have been burned for atheism and blasphemy, who were neither atheists nor blasphemers. This was the lot of the primitive Christians, and also of the Waldenses9 and other martyrs, under the tyrannical union of church and state, in the apostate christian church. However Vanini and others have publicly taught atheism, Spinala, and even Hume and others have taught doctrines that evidently lead to it, though they have denied the charge.10 An atheist in opinion, must believe miracles of a more extraordinary kind than any that are recorded in the scriptures. They must believe that every thing created itself in the order and connexion in which it is found. To this purpose, it was well observed by one condemned to be burned for atheism by the inquisition, who, when going to the stake, lifted a straw, and holding it up, said, That if he denied the being of a God, that straw would condemn him, for it could not make itself. The Hussites, &c. were burned for blasphemy—They blasphemed the church, by denying her infallibility.11 They blasphemed the Blessed Virgin, by not worshipping her as the immaculate mother of God.

Thus much I observe by the way, with a view to the numerous charges of atheism, blasphemy, &c. interspersed through the Sons of Oil, accompanied with an unusual number of notes of astonishment, to supply, it is presumed, the want of argument, of which I design to take no detailed notice.

In page 8, after having stated what, in his opinion, is the extent of Christ’s power, he says, “This universal dominion committed to him, as it respects the human family, in its administrations, consists in two great branches; namely, magistracy and ministry.”

He then proceeds to show, in eight particulars, wherein these branches differ; and again, in seven particulars, wherein they agree, to the 30th page. In page 15, he says, “They agree in this, that God the Father, Son and Spirit, is the original fountain from which they flow. To suppose any power or authority whatever not originating from God, essentially considered, would necessarily lead to atheistical principles. It must therefore emanate from him. Rom. xiii. 1. ‘There is no power but of God.’ To the same purpose is 2 Cor. v. 18. ‘All things are of God.’ Civil power was already shewn to originate from God, as Creator, and to be founded on his universal dominion, as the King of nations. Jer. x. 7. And though all ecclesiastical power flows immediately from Christ, as Mediator, yet it is radically and fontally in a three-one God. All the right and authority of Christ, as Mediator, is originally derived from God, as well as civil power.”

If this had not been laid down as a fundamental principle of his system, it might have passed unnoticed. The scripture texts which he applies to support this theory, were revealed for another purpose. Rom. xiii. 1. is expressly applicable to civil power. Of this the apostle says, “Let every soul be subject to the higher powers; for there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God.” In Cor. v. 18. the apostle is treating of the hope of glory, walking by faith, the terrors of the Lord as an excitement to be reconciled to him through Christ, and of the constraining love of Christ, as a reason why those that are in Christ, should be new creatures; and the apostle assures them that all these things, of which he is there treating, are of God, who had reconciled them to himself, and committed to the gospel ministry the word of reconciliation. There is not a word here about a civil branch of Christ’s kingdom, of which he himself testified that it was not of this world.

Man can have no competent knowledge of God, nor render to him any acceptable worship, but agreeably to the discoveries he has given of himself. To man, in his state of innocence, God revealed his divine perfections and his will, so far as was necessary for the worship and obedience required in that state. Even after man had revolted from God, so much of his divine perfections and of his will, are revealed in the works of creation and providence, and particularly, in the relation in which men stand to God, and to each other, as renders them without excuse in not knowing and worshipping him as the true God. This the apostle calls the law written in the hearts of the gentiles, by which their reason and judgment, viz. their conscience, was regulated in approving or condemning their own conduct. Rom. ii. 15.

After man had revolted from God, in addition to former discoveries, he revealed himself as merciful, as a God pardoning iniquity through a Mediator; but did not so clearly reveal the Deity, as subsisting in three distinct persons, as to render the belief of it a condition of holding communion with him in his ordinances, until by the coming of Christ in the flesh, by whom life and immortality, and particularly the doctrine of the trinity, the spiritual nature of Christ’s kingdom, and the resurrection from the dead, were more fully brought to light, and henceforth became, fundamental articles of the faith of christians: consequently, whoever being favoured with the christian scriptures, worship God in any other way than he has therein revealed himself, worship a false God, and are, in so far, idolaters, however they may declaim against idolatry, superstition, popery, &c. in others.

The whole old and new testaments, and even the works of creation and providence, reveal the object of worship to be one God; but the new testament has not only clearly revealed that one God to subsist in three persons, but that christians, in the exercise of faith and worship, hold distinct communion with these three adorable persons. With the Father in love. “God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son,” &c.—John iii. 16. With Christ in grace—John i. 14, 17. “The only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth—Of his fulness have all we received grace for grace—Grace and truth came by Jesus Christ.” And with the Holy Ghost in comfort—John xiv. 16, 26. “He shall give you another Comforter to abide with you—But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, shall teach you all things.” That well known text, commonly called the christian doxology, 2 Cor. xiii. 14. “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Ghost, be with you all,” is full to the purpose, and is used to conclude the public worship in most, if not all, christian churches, however they may differ otherwise. It is so used even by the church of Rome.

In order to support his system, the author unites what God has most explicitly kept separate. Page 8. “This delegated power is most conspicuous in the person of the Mediator. Into his hands universal dominion is committed. Matth. xxviii. 18—“All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth.” From this he deduces what I have quoted above, viz. “This universal dominion committed to him, as respects the human family, consists in two great branches; namely, magistracy and ministry.” Again, “though both these branches are put under the Mediator’s controul, yet they are so under different regulations,” &c.

Here it is to be observed, that the author confounds the administration of providence given to Christ, by the Father, whereby he rules over men, angels and devils, in consequence of the Father having given all power in heaven and earth unto him, with that kingdom “which he purchased with his own blood;” Acts xx. 28. and which is, Eph. i. 14. called “the purchased possession,” viz. the church, called a peculiar people, &c. 1 Pet. ii. 9. and in Eph. i. 23. “His body, the fulness of him that filleth all in all;” and that this evident distinction might be left without a shadow of doubt, the apostle says. Col. i. 24. “For his (viz. Christ’s) body’s sake, which is the church.” The church, in contradistinction from the kingdom of this world, is frequently called the kingdom of God.

That Christ’s purchased kingdom was specifically distinct from the general kingdom of Providence, the administration of which was given to Christ, is evident from the whole doctrine and practice of Christ and his apostles. They absolutely declined interfering with the government of nations, or the relations among men, otherwise than by expounding and applying the moral law to the conscience. They had recourse only to spiritual armour, and engaged only in spiritual warfare. The Saviour’s solemn dying testimony, however, ought to be conclusive with every sober enquiring mind. When he was brought before Pontius Pilate, by whom he was asked, “Art thou the king of the Jews?” To this the Saviour answered: “My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered to the Jews; but now is my kingdom not from hence.” This the apostle calls the good confession which Christ Jesus witnessed before Pontius Pilate. On this precious, but much neglected text, the learned Dr. B. Hoadly, bishop of Bangor, preached a celebrated sermon, which procured the resentment of his high church brethren, but having the testimony of Christ and the apostles on his side, he succeeded in an arduous controversy, occasioned by that excellent sermon, a few lines from which I will insert.12

“The laws of his kingdom, therefore, as Christ left them, have nothing of this world in their view; no tendency either to the exaltation of some in worldly pomp and dignity, or to the absolute dominion over the faith and religious conduct of others of Christ’s subjects. It is essential to it, that all his subjects, in what station soever they may be, are equally subjects to him; and that no one of them, any more than another, hath authority, either to make laws for Christ’s subjects, or to impose a sense of their own on the established laws of his kingdom, which amounts to the same thing as making new laws.”

If the laws of Christ in their principles, as well as in their extent, are perfect, with respect to the rules and orders of his own house, which all the different denominations of presbyterians profess to allow; the author’s system is contrary to this profession: for neither in the fourth chapter to the Ephesians, nor in the twelfth chapter to the Romans, nor in any other portion of the New Testament that treats of the officers or orders of Christ’s house, do I find kings or civil magistrates of any kind of political governments, enumerated. They, therefore, can have no legal authority in the church, much less can they have any legislative authority over it. This I take to be a fair conclusion.

I object to the use of the phrase “delegated power,” as applied by the author to the Saviour, with respect to his kingdom. It is not used in scripture. A delegate is of the same import as a deputy. The power of deputies or delegates among men, is always subordinate, and subject to the instructions and controul of the superior, and likewise liable to be removed; this is implied in the very term. This can by no means apply to Christ’s spiritual kingdom. The apostle does not call Christ a delegate, “but a son over his own house, which house are ye,” viz. the church. Nor can it be, with propriety, applied to him as administering the kingdom of providence. It is properly a given kingdom committed unto him, if we are contented with the Saviour’s own words. Mat. xxviii. 18. “All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth.” John v. 22. “The Father judgeth no man, but hath committed all judgment to the Son of Man.”