Читать книгу To the Break of Dawn - William Jelani Cobb - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Microphone Check

ОглавлениеAn Intro

NEW YORK, CIRCA 1986

That was us: the sweat-baptized, blue-light basement apostles of the breakbeat. We, the b-boy delegates of our five-borough universe, eyes hidden beneath baseball caps pulled low, uniformed in ?Guess, Kangol, and Adidas Olympic Team training gear. Our ranks cued waaay back to the subway lines that had delivered us to this place: Union Square, the nightspot deriving its name from the section of Manhattan where it was located. If you came from around our way, South Queens, specifically, then you gathered your tribe at 163rd Street and Hillside Ave and took the E to Lexington. Then you caught the downtown #6 to 14th Street, which delivered you to the far end of the Square.

At the front you encountered Muscle D, a brother swollen to a rippled abstraction, barely contained by his nylon tees and capable of literally moving the crowd. Down below was a consecrated dance-floor, the theater for our repertoire of movements: the Wop, the Rambo, the Fila, the Biz, the Prep. The true disciple could tell you that Rakim was there, the headlining act on the opening night at Union Square. That disciple would know that Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince were to be the second act. Or that Biz-Markie rolled up in that spot on the reg, self-advertising with the boldfaced B-I-Z emblazoned on his cap—as if he was worried you would mistake him for Kool Moe Dee. You would remember the smell of it, if you had ever been there, the blunt-heavy air mixed with sweat, leather, Polo cologne, and some other indefinable element—a calibrated cool, perhaps—that we were so filled with that it must have seeped from our pores into the atmosphere also.

This is my romantic memory of the distant past. But the charitable will indulge my personal mythologizing for a moment.

The truth is that we seldom understand what era we are living in until that era is over. At the time I thought I was merely experiencing a hot moment in Manhattan, but across the span of two decades it has aged into … something else. A mental placeholder for a hundred other forgotten memories. The signpost for an innocence that long ago disappeared into history. The space that was Union Square is now a pet store, one of those national chains hustling overpriced canine couture. Our Benetton-and-Kangol gear has long fallen into disfashion and our once-young delegates to the five-borough assembly are now men and women approaching middle age.

And still something of it remains real.

There is an inventory of rhymes, some over twenty years old, that remain cataloged and stored in my memory. I can replay, line for line, Kool G. Rap’s classic “Poison,” or the infamous battle between Kool Moe Dee and Busy Bee. Name a track and I can tell you where I was when I heard it for the first time. “Rapper’s Delight,” the Sugar Hill Gang, 1979, a yellow house on 200th Street and Hollis Avenue. “Lights, Camera, Action,” the Treacherous Three, 1982, basement apartment on Foch Avenue, off 142nd Street. “Sucker MCs,” Run DMC, 1983, on the 8th-grade senior trip at a roller rink on the north side of town. “Ego Tripping,” Ultra Magnetic MCs, Union Square, 1986. “Rebel without a Pause,” Public Enemy, corner of Linden and Merrick boulevards, 1987.

In the ultimate equation, place and time don’t matter, though—the book of Rakim teaches that it ain’t where you from, it’s where you at. But a brother still has love for the local. On the streets of South Queens, New York, in the mid-80s we honed verbal skills, traded our elementary freestyles, and chased after reputations for lyrical flow. At the part of Hollis Avenue that runs past the park on 205th Street, they used to steal power from the street lights and throw illegal jams back when Hollis Crew and Southside Posse were still civil warring. At I.S. 238, on Hillside and 179th Street, an eighth-grade nemesis named James Todd Smith handed me his autograph, saying that he would be famous one day. The signature read simply: Cool J—this was in the days before he prefaced his name with the Double Ls. Along Farmers Boulevard cats used to get their rhyme skills (and chins) tested on the Square. Liberty Avenue was where some of the illest did their dirt and whose residents always rolled deep to the shows at Club Encore.

Hip hop culture is a four-legged stool, its artistic pillars of deejaying, graffiti art, rapping, and b-boying coming into existence in rapid succession in the early 1970s and each influencing the ways in which the other evolved. In those early days, before artistic apartheid took hold, it was nothing for a rapper to moonlight as a graffiti artist or for a b-boy to also be known for ripping microphones. Long before low-wattage celebrities thought to brand or cross-promote themselves, artists were rapping and tagging graffiti under the same alias as to ensure that one’s rep received its maximum dissemination.

Recognize: before middle-aged pundits started lamenting hip hop’s “values,” before rappers became unpaid boosters for the booze du jour, before ice was anything but frozen water, there was this: two turntables and a microphone. Before hip hop was old enough to see over the dashboard of America, the battles weren’t between rappers in different time zones—it was all about inter-borough strife back then. Them Brooklyn cats had it in for the brothers from uptown; Bronx heads were constantly flexing on Brooklynites and nobody was feeling Queens. I remember when deejays at spots like Union Square and the Latin Quarter would ask if Queens was in the house as a semi-joke. Asking if Brooklyn was in the house was always a rhetorical question. In those days, our Kazal-goggled, black bomber-wearing assemblies kept our mouths shut fearing larceny from the Bed-Stuy, Harlem, South Bronx axis of evil. To cut to the quick: Queens was known for getting played.

Run & them changed that though.

I speak of the trio that put Queens—a borough that isn’t even completely on the New York City subway map—on the musical one. Kicking open the doors for acts like LL Cool J, MC Shan, Salt-N-Pepa, Kool G. Rap, Main Source, Nas, Ja Rule, and 50 Cent, they were responsible for transforming Queens status from that of cultural pariah to hip hop epicenter. For a good bloc of the music’s history, between “King of Rock” and KRS-One’s loathsome drive-by “The Bridge Is Over,” Queens was officially running shit. These cats helped make it (slightly) safer to be from the city’s largest borough and represent at hip hop shows. That Run, D, and the late scratch technician Jam Master Jay—the first legitimate superstars of the new music—would straight up claim Hollis, Queens, on wax all but reversed the previous borough-pecking order. These are small things in the grand flow of life and history, but they held import at the time. These were our battles until time and life delivered more weighty concerns onto our shoulders and then the music would reflect those new realities too.

Before we arrive at the mandatory Fanon quote, let us state the obvious: hip hop has, in the course of three decades, become the dominant form of youth culture on earth. It has ridden a tidal wave of American hegemony to the farthest expanses of the globe, carrying with it the complex, incomplete, and contradictory visions of those who created it as simultaneously the richest class of exploited people in world. Hip hop is culture. Hip hop is politics. Hip hop is economics. And it is something additional and unnamed. And now the Fanon: Each generation must, from relative obscurity, discover its mission. It will either fulfill it or betray it.

Hip hop is so central to the development of the post-civil rights generation of black people that it’s nearly impossible to separate the music from our politics, economic realities, gains, and collective shortcomings. When I first heard Public Enemy’s insurrection theme song “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” I literally did not know it was legal to speak such words on the radio. The distant echoes of the Nation of Millions album have been reverberating ever since. It was partly responsible for my dawning interest in the history of black peoples scattered throughout the world wholesale between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Each generation is imbued with its own unique moments of collective understanding, moments frozen in history when a sprawling set of people watched an iota, a fragment, or a vast chunk of their innocence slip away. In the case of those of us in the so-deemed “hip hop generation,” our where-were-you moments were almost universally framed by hip hop narrative. The Rodney King beating and subsequent Los Angeles Riots—all but predicted and pre-narrated by Ice Cube’s warning on Amerikkka’s Most Wanted that the LAPD’s role was “to serve, protect and break a nigga’s neck.” The horrors of September 11 bore an eerie resemblance to Rakim’s Nostradamus-like tale of urban terrorism on “Casualties of War.” The deaths of cornerstone artists Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. stole away a different kind of innocence from a generation that already been deemed cynical and lacking in idealism. That their deaths came to be seen in some quarters as “assassinations” on par with those of Malcolm or King illustrated not only how blurred the definitions of celebrity and leadership have become since the civil rights era, but also how few imaginative leaders have been cultivated since then. In their wake, charismatic artists were mistaken for political leadership. For me, the murders of musicians placed the sad dilemmas of black America in high relief: after a century that witnessed the rise of Jim Crow, lynching, black migration, slumification, Vietnam, incarceration, dissolving families, crack, and AIDS, African Americans—on the verge of a new millennium—were now killing each other over poetry.

That reckoning led me to stop listening to hip hop for almost four years believing it to be what I called “the soundtrack to self-inflicted genocide.” The music that first articulated my understanding of the world around me had gone from obscure to ubiquitous; it had simultaneously become powerful and useless. I understood what Common had been metaphorically lamenting on “I Used to Love H.E.R” when he rhymed

I see her in commercials She’s universal She used to only kick it With the inner city circle

That remained the state of affairs until I was dragged to a Roots concert in late 2000. The dense crowd that had committed entire albums to memory, the hoodies and baseball caps, the antiseptically white Nikes, the freon cool, the absolutely kinetic vibe and the unrelenting heat of the performance that night. This was hip hop. This was truth. Over the course of that two-hour set, I came to remember hip hop had once been affirming, that it had once actually been real and hadn’t needed to obsess over insecure cliches like “keeping it real.” In the end, it was the pure lyrical genius of figures like Black Thought, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, Pharoahe Monch, and Common that led me to re-engage with hip hop on the level of art—even as my evolving humanist politics put me at odds with much of the form’s content. To cut to the quick, it was a gradual understanding that hip hop was both an aesthetic statement and a political one, that the music was, in Mos Def’s terms, Black on Both Sides.

Dig through the volumes of writing about hip hop and what emerges is one black side. The growing literature on hip hop features a thousand different spins on the theme of music as a social politic. And for good reason. In the space of a single generation, hip hop has evolved from the shunned expressions of disposable people into the dominant cultural idiom of youth globally. Rappers have literally gone from being maligned street poets to being A-list Hollywood stars, recording industry executives, film producers, and running up the score on their opponents in the culture wars. Hip hop has highlighted the black impulse toward verbal and musical invention and, at the same time, turned the most problematic, despair-riddled elements of American life into purchasable entertainment. The hip hop industry is largely responsible for the global re-dispersal of stereotypical visions of black sexuality, criminality, material-obsession, violence, and social detachment. That one can fly halfway around the world and be greeted in the Czech Republic by young men who speak no English, but regard you with a high-five and say “What up, Nigga?” is a bitterly ironic testament to the power and appeal of African American culture in the age of high capitalism.

But at the same time, hip hop is not fundamentally a political movement—no matter how many political implications the music and its mass marketing have. In 1926 Langston Hughes, as he rebelled against the artistic strictures prescribed by official black leadership, wrote the essay “Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” in which he pointed out that art and politics have had a notoriously rocky marriage. Hip hop is many things, but most prominently it is a musical movement corner-stoned by a tradition of verbal creativity. That is to say that hip hop is not only a contribution to black music, but also black language arts. Future anthologies of black literature will need hip hop citations and future students will (if they haven’t already) turn in term papers with titles like “Metaphor and Simile in the Works of Lauryn Hill and Langston Hughes.”

And on this last point, we have to be clear. Much has been made of the multiculturalization of hip hop in the years since it first rumbled out of the Bronx. On one level, this is historically inaccurate in that hip hop began as a multicultural movement. It represented the artistic communion between young Latinos, West Indians, and post-migration African Americans. In the 1970s the South Bronx became to this diverse collection of peoples what Paris was in the 1930s to the diverse body of peoples who had been colonized by the French and who eventually created the Negritude Movement. It was to these people what London was to the body of Caribbean and African intellectuals who met and organized the anticolonial movements of the 1940s. And it was what Harlem had been in the 1920s, when a similar group of peoples—West Indians like Claude McKay, Southern migrants like Zora Neale Hurston, and Latinos like Arthur Schomburg—created the artistic movement that came to known as the Harlem Renaissance.

But this new multiculturalism is global and international and also refers obliquely to the vast numbers of white Americans who now participate in the culture. Hip hop, we are told, has gone universal. And yet, my references to this as a black art form are intentional. Seventy-eight years ago, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, the sage W. E. B. Du Bois remarked that “As soon as true Negro art emerges, it is said ’That person did this because he is an American, not because he is a Negro; as a matter of fact there is no such thing as a Negro.” Such is the case with the ongoing perceptions of jazz and blues as quintessentially “American” artforms—decreasingly owing their existence to the social quarantine of Jim Crow and the aesthetic laboratories that generations of Negro artists created within it. By this logic, Rakim, Jay-Z, MC Lyte, KRS-One, Lauryn Hill, OutKast, Scarface, Ice Cube, Common, and Snoop Dogg are Americans, not Negroes—and Eminem must be the President.

The truth is that it is possible to be both specific and universal simultaneously. The legions of mic-grabbing rhyme spitters in Germany, Japan, France, and Amsterdam are no more contrary to the black roots of hip hop than Leontyne Price was a threat to the Italian roots of opera. Hip hop is literally a product of the African Diaspora—with breakdancing owing its existence to the Afro-Brazilian martial art form of Capoeira, deejaying growing from the genius of Caribbean migrants to the United States, and MCing evolving at the crossroads of a number of verbal traditions. I use the term black as an—admittedly awkward—reference to that body of Africa-derived cultures, specifically those of North America and the Caribbean, and the term African American to describe the group of Africa-descended peoples in the United States.

And now a confession: of the four pillars of hip hop—breaking, graffiti art, deejaying, and rapping—I am focusing on the craft of the MC, the most widely recognized of hip hop participants. There are volumes to be spoken on the artistic skill of the turntablist; the re-made acrobatics of the b-boy, who fashioned a new form from the Capoeira martial art created by stolen Africans in Brazil; and the alphabetic abstraction of the graffiti tagger. But I’ll leave that for future writers.

I’m talking specifically about MCs in these pages, not the general category of rappers. Every MC raps, but not every rapper is an MC. Truth told, there are scores of successful rappers who have never met an actual MC. Like Madison-Avenued, focus-grouped novelties, rappers are created in accord with the reigning flavor of the nanosecond. Right about now, most rappers exist as living product placements, their gear, their rides, their whole set-up as deliberately schemed as that can of Coke downed by your favorite action hero before he splits to do battle with the special-effected forces of evil. Only the mad niche-marketers of American hypercapitalism could conceive of the modern rap video—basically a commercial in which products advertise other products. It would be easy to freestyle on the soul-nullifying effects of capitalism on art, but the point is that the music, the art of hip hop, has to be understood as distinct from the cellophane-shrouded rap products sitting in the music bin at Wal-Mart.

Flip on your TV, turn on the radio, open a magazine and there’s a good chance that there’s a rapper floating on your medium of choice. An MC, though, is a whole ’nother thing entirely. Microphone Controller, Mic Checker, Master of Ceremonies, Mover of Crowds, in hip hop, the letters MC are as undefined as the X that followed Malcolm’s name.

The genealogy of the MC runs all the way back to hip hop’s fetal days when the DJ was at the center of the culture and the Master of Ceremonies was essentially a sideman. The group was called Grand Master Flash and the Furious Five for a reason: Flash’s eye-blurring hand speed and slick scratches had made him a boulevard celebrity long before the heads on the boulevard got wise to the vocal talents of Cowboy, Melle Mel, Rakim, Mr. Ness, or Kid Creole. The DJ selected the array of sounds that the masses would move to, operated literally as the architect of a vibe. The DJ’s primacy—and the MC’s secondary status—had started to change by the time you got to groups identified by a single common name like the Cold Crush Brothers or the Fearless Four. The situation was clearly reversed when you got to Run DMC & Jam Master Jay—two rappers and a DJ who were more commonly referred to as just Run DMC.

The difference between a rapper and an MC is the difference between smooth jazz and John Coltrane, the difference between studio and unplugged. Or, to cop a line from Alice Walker, the difference between indigo and powder blue. Nelly is a rapper; KRS-One is an MC twenty-five hours a day. Lauryn Hill is, straight up and down, an MC’s MC; the Fresh Prince was an MC; Will Smith is a rapper. Nas has been an MC since he breathed his first; P. Diddy and Master P. are rappers down to their DNA.

The rapper is judged by his ability to move units; the measure of the MC is the ability to move crowds. The MC gets down to his task with only the barest elements of hip hop instrumentalization: two turntables and a microphone. On that level, the Miami basspreneur Luke, who didn’t even necessarily rhyme, was closer to being an MC than Hammer, who did rhyme—or at least attempted to. The MC writes his own material. The MC would still be writing his own material even if he didn’t have a record deal. A rapper without a record deal is a commercial without a timeslot. Regarding the difference between rapper and MC, KRS breaks it down like this:

A dope MC is a dope MC With or without a record deal, all can see And that’s what KRS is, son I’m not the run of the mill ‘cause for the mil’ I don’t run

Still, you can get yourself in trouble thinking that art is easily categorized. Jay-Z, Eminem, Notorious B.I.G., 50 Cent, Tupac Shakur, DMX, and LL Cool J are all MCs who are also rappers, meaning they have managed to exist within the commercial arena while maintaining their integrity as artists. To avoid confusion, I use the term rapper as a general reference to hip hop vocalists—and MC when I mean to connote that specific brand of verbal marksmen who were forged in the crucible of the street jam, the battle, and the off-the-top-of-the-dome freestyle.

There has emerged over the last ten years a body of hip hop music criticism from the pages of niche outlets like Source, XXL, Vibe, the now-defunct Blaze, hip hop websites, and mainstream music magazines like Spin and Rolling Stone—but the criticism most often deals with how well a particular rapper or group of rappers met commonly accepted standards for the form, not the exploration of those standards themselves. My intent here is to understand hip hop as an aesthetic, not necessarily a social movement. To deal, in other words, with the art on its own terms. The issues of sexism, violence, homophobia, and materialism have been raised and thoroughly treated by other writers. This is not a history of hip hop, though it necessarily contains historical elements. The history of the music has been chronicled in songs, magazines, books, and websites. The history and politics of the art form as well as the generation that created it have been chronicled in works such as Bakari Kitwana’s Hip Hop Generation, Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, Ego Trip’s Book of Rap Lists, Gwendolyn Pough’s Check It While I Wreck It, Tricia Rose’s Black Noise, and Mark Neal and Murray Foreman’s That’s the Joint, among others. There is always room for additional voices, but hip hop’s political and social elements can at last lay claim to a substantive body of literature.

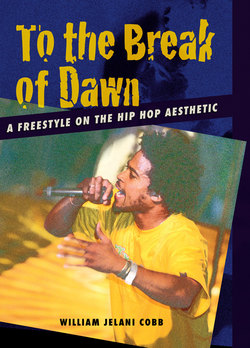

So this book aims for a different kind of conversation. It is a treatment of themes in the music and culture—some of which have historical threads. To the Break of Dawn is an extended liner note on the artistic evolution of rap music and its relationship to earlier forms of black expression. It is also not meant to be exhaustive. There are plenty of rappers you won’t find discussed in these pages. Hip hop is diverse and subdividing by the minute. Still it is worthwhile to distill commonalities in the craft of rapping up to this particular point.

This book is divided into five sections: “The Roots” traces hip hop’s relationship to the ancestral forms of expression, particularly blues and the oral tradition. It takes direct issue with those mumble-mouthed and cliché assertions that hip hop is less than a full descendant of the traditions of African American and Diasporan cultures in the United States. “The Score” charts hip hop’s aesthetic evolution from its inception in the South Bronx through its standing as a complex, multi-layered music that has expanded enough to actually have regional and stylistic sub-genres. “Word of Mouth” examines the cultural and literary elements that are the foundation of MC culture. In hip hop we find the practice of the entire palette of poetic techniques; this part charts the innovative ways in which varieties of rhyme, metaphor, simile, assonance, and alliteration are used inside the art form. “Asphalt Chronicles” details the importance of the storytelling tradition within hip hop. Hip hop, more than any other popular descendant of the blues, places emphasis upon narration. The ways in which story is used within hip hop sheds light on both the genre’s musical roots and its relationship to the tradition of black autobiography in this country. The final part, “Seven MCs,” looks at the contributions of seven artists to the evolution of the music. This is not one of those tired “top 100” lists that seem to be the mainstay of magazines and cable music shows, but a look at what each of these artists brought—or brought out—in the music. It is possible to understand the music through the lens of an individual’s body of work and that is what this final part seeks to achieve.

To the Break of Dawn is my attempt to enter this dialogue; it examines the aesthetic, stylistic, and thematic evolution of hip hop from its inception in the South Bronx to the present era of distinctly regional sub-divisions and styles. Back when I was a word-scribbling acolyte trying to make subject and verb agree, I was given the age-old advise to “write what you know.” And what I knew was hip hop. The first words I ever wrote seriously were rhymes—material for my stalled adolescent career as South Queens’s own MC Trate, the self-professed Freestyle King. My first conscious goal when I started writing essays was to sound on a page the way Chuck D sounded on a record. This book reflects my particular relationship to the art form. Although I’ve heard and dug hip hop in all its multi-regional diversity, I am, at my core, an old-school East Coast cat—a reality that the reader will likely note in these pages.

My sincerest hope is that this book remains true to the art form that first introduced me to creative genius. In the years since the movie Brown Sugar premiered, it has become cliché to ask When did you fall in love with hip hop? But the question still warrants a response. My answer is this: from the first second I heard the first rhyme delivered over the first break beat. I loved it from the time I was a heavy-lidded ten-year-old struggling to stay up to 2 A.M. to tape The Mr. Magic Show on WHBI to my present standing as a man just old enough to begin idealizing his youth. To cop a line from Common, I used to love her. And twenty-five years after that first blessed encounter, despite numberless frustrations with what she has become, I still do.