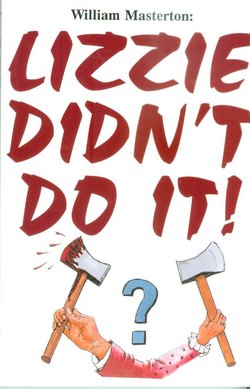

Читать книгу Lizzie Didn't Do It! - William Psy.D. Masterton - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3: THE INQUEST

ОглавлениеAs pointed out in Chapter 1, the chief of police and the mayor of Fall River, Marshal Rufus Hilliard and Doctor John Coughlin, were convinced by Saturday, August 6, that Lizzie Borden murdered her father and stepmother. On Monday, August 8, they, along with Medical Examiner Dolan and Detective Seaver of the state police, held a conference to review the evidence against Lizzie. They were joined by Hosea Knowlton, District Attorney for Bristol County. Knowlton, shown at the right of the sketch below, was 45 years old. He was a short, stocky, squarefaced man known for his bulldog-like tenacity.

FIGURE 3.1 Jennings (left) and Knowlton (right)

The conference, which started at 5 P.M. and went on past midnight, was inconclusive. Knowlton cautioned against arresting Lizzie at this point. In the first place, there was no physical evidence linking her to the crime. The police search of the premises had failed to produce either a bloody hatchet or bloodstained clothing. Moreover, Lizzie was in effect under house arrest already; she had been told not to leave 92 Second Street.

The conference did agree upon one thing; Bridget Sullivan should be questioned more closely as to what she knew about the crime. She was summoned to the Fall River police station at 10 A.M. on Tuesday, August 9. One thing led to another; what started as an interrogation of Bridget evolved into a formal inquest into the crime. This was presided over by Judge Josiah Blaisdell. The inquest was closed; no member of the press was allowed in the courtroom when Knowlton was examining witnesses.

Over the years, the testimony of all the witnesses except one has been made public. Bridget Sullivan's testimony seems to have disappeared; no one really knows what she had to say. Of the remaining witnesses, all except four (Lizzie Borden, Hiram Harrington, Augusta Tripp and Sarah Whitehead) testified later, either at the preliminary hearing (August to September, 1892) or the trial (June 1893). We'll concentrate here upon the four witnesses who never appeared upon the stand in open court, with particular emphasis, as you might expect, upon Lizzie Borden.

Augusta, Hiram and Sarah

Hiram Harrington, Andrew's brother-in-law (and least favorite relative) was a blacksmith. Sarah Whitehead, Abby's halfsister and closest confidante, was a young married woman (age 28) with two small children. Augusta Tripp was a friend of Lizzie and former schoolmate. All three of them were questioned as to the relationship between Abby and Lizzie. There was general agreement that the two women were not what you would call congenial. Augusta Tripp, who liked Lizzie, put it delicately:

Q. (Knowlton) "What can you tell us about the relations between Lizzie and her mother, so far as you observed it, and heard it from Lizzie?"

A .(Mrs. Tripp) "All I can tell you is that I don't think they were agreeable to each other."

Q. (Knowlton) "What made you think so?"

A. (Mrs. Tripp) "I have seen them together very little . . . They did not sit down, perhaps, and talk with each other as a mother and daughter might. They were very quiet."

Hiram Harrington, who didn't like Lizzie, was more critical:

Q. (Knowlton) "When Lizzie spoke about [Abby] last winter, what did she say?"

A. (Harrington) "I don't know as I could tell any more than to speak kind of sneeringly of Mrs. Borden. She always called her Mrs. Borden or Mrs. B. I don't know as I could remember anything to put together to make any sense."

Q. (Knowlton) "Did she speak in an unfriendly way of her?"

A .(Harrington) "Unfriendly, yes."

Q. (Knowlton) "It was understood that there was trouble in the family?"

A. (Harrington) "Oh, yes; there has been, I guess. For several years, I guess."

Curiously, Sarah Whitehead was non-committal about the relationship between Abby Borden and her stepdaughters:

Q. (Knowlton) "Did [Mrs. Borden] come to your house?"

A. (Mrs. Whitehead) "Yes, sir, she came very often."

Q. (Knowlton) "Did she seem to be on good terms with Emma and Lizzie?"

A. (Mrs. Whitehead) "She never seemed to say but very little about them; she was a woman who kept everything to herself."

Yet, outside the courtroom, Mrs. Whitehead told two police officers that Lizzie did not get along well with Mrs. Borden!

Hiram Harrington and Sarah Whitehead apparently decided that, as long as they were on the witness stand, they might as well get a few other things off their chests. Hiram got in one last dig at Andrew, pointing out that not only did he refuse to speak to his brother-in-law, he wouldn't even stay in the same room with him. Sarah Whitehead made it clear that she didn't like either Lizzie or Emma. "I always thought they felt above me," she said. She almost never went to the Borden house, "on account of those girls."

Incidentally, Alice Russell, in her inquest testimony, gave a very rational explanation of the strained relationship between Lizzie and Abby. She said, "Their tastes differed in every way; one liked one thing, the other liked another." She went on to talk about tension between the girls and their father. "Mr. Borden was a plain living man with rigid ideas and very set . . . He did not care for anything different . . . They would have liked to be cultured girls and would like to have had different advantages."

Lizzie's Story

At 2 P.M. on Tuesday, August 9, Lizzie Borden went to the Fall River police station to testify at the inquest. She went on the stand that afternoon, returned on Wednesday morning, and was recalled on Thursday, August 11. Before she testified, Andrew Jennings, the Borden family lawyer, shown at the left of Figure 3.1, asked that he be allowed to counsel Lizzie. Judge Blaisdell turned him down; the inquest was closed, particularly to lawyers. Jennings did, however, represent Lizzie in all subsequent court hearings on the Borden case.

It turned out that Lizzie could have used a lawyer at the inquest; she came close to breaking down a couple of times. Knowlton started out very mildly, establishing that her name was Lizzie, not Elizabeth, that Andrew Borden had only two living children, and other trivia. Then, during a tedious discussion of the dates at which John Morse had visited the Bordens, Knowlton suddenly turned sarcastic. Lizzie, in response to a question, asked him if he remembered the winter that the Taunton River froze over. Knowlton snapped, "I am not answering questions but asking them."

From that point on, Knowlton became an aggressive, relentless prosecutor. Lizzie seemed to lose her composure, frequently showing confusion. When Knowlton asked her where she was when her father came back from downtown on August 4, she couldn't remember whether she had been downstairs or upstairs. Knowlton pressed her on this matter, prompting Lizzie to exclaim:

"I don't know what I have said. I have answered so many questions and I am so confused that I don't know one thing from another. I am telling you just as nearly as I know how."

Later on, Knowlton seemed on the verge of losing his temper when the following exchange took place:

Q. (Knowlton) "Miss Borden, I am trying in good faith to get all the doings that morning of yourself and Miss Sullivan and I have not succeeded in doing so. Do you desire to give me any information or not?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "I don't know it; I don't know what your name is."

Perhaps the worst moment for both of them came when District Attorney Knowlton, for some inexplicable reason, insisted that Lizzie describe her father's appearance when he lay dead on the sofa.

Q. (Knowlton) "You saw his face?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "No, I did not see his face, because he was covered with blood."

Q .(Knowlton) "You saw where his face was bleeding."

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Yes, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "You saw his face covered with blood?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Yes, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "Did you see his eyeball hanging out?"

A. Lizzie Borden) "No, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "See the gashes where his face was laid open?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "No, sir."

When this interrogation finally ended, the stenographer entered the following statement into the court record: "Witness covers her face with her hand for a minute or two; then examination is resumed."

Altogether, Lizzie's inquest testimony filled more than forty single spaced pages. Here we'll concentrate on a few of the more relevant and interesting topics covered in the three days she was on the stand.

One thing that Knowlton asked Lizzie about was her relationship with Abby Borden:

Q. (Knowlton) "You have been on pleasant terms with your stepmother . . . ?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Yes, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "Cordial?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "It depends upon one's idea of cordiality, perhaps."

Q .(Knowlton) "Cordial according to your idea of cordiality?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Quite so."

Q. (Knowlton) "What do you mean by quite so?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Quite cordial. I do not mean the dearest of friends in the world, but very kindly feelings and pleasant. I do not know how to answer you any better than that."

Later on, near the end of her testimony, Lizzie described the incident, five years prior to the murders, that led her to call her stepmother "Mrs. Borden" rather than "mother". It seems that Abby's half sister, Sarah Whitehead, owned the house at 45 Fourth Street jointly with her mother, Mrs. Oliver Gray. Mrs. Gray wanted to sell the house, which would have left Sarah homeless. To prevent that, Andrew Borden bought out Mrs. Gray's interest and gave it to Abby. Lizzie told Knowlton:

"I said if he gave that to her he ought to give us something; told Mrs. Borden so. We always thought she persuaded father to buy it. At any rate, he did buy it and I am quite sure she did persuade him. I said what he did for her people he ought to do for his own children. So he gave us grandfather's house." [That was the house on Ferry Street, where both Emma and Lizzie were born. On July 15, 1892, three weeks before the murders, Andrew bought it back from the girls, paying them $5000.]

According to Lizzie, that was all the trouble she ever had with Abby. When Knowlton asked her why, after this incident, she stopped calling Abby "mother", her answer was a simple one. "Because I wanted to", Lizzie said.

Lizzie testified that she last saw her father alive, resting on the sofa, at about 10:55 A.M. on the morning of August 4. At that point, she went to the barn in hopes of finding lead sinkers that she needed for a fishing trip with friends the following week. On the way to the barn, she picked up some pears that had fallen from the trees in the back yard.

While Andrew was being killed in the sitting room, Lizzie claimed she was rummaging through a box resting on a work bench in the barn loft. In the box, she found some nails, a doorknob and the thing she was searching for: flat pieces of lead suitable for sinkers. At more or less the same time, she was munching pears and occasionally looking out the window. Apparently she was in no hurry; as Lizzie put it, "I don't do things in a hurry."

Knowlton wasn't buying any of this. For one thing, Lizzie claimed earlier that she went to the barn to get a piece of iron, not lead. More important, he was convinced by now that she was in the house chopping up Andrew around 11 A.M., not in the barn loft. Knowlton hammered away at Lizzie's alibi, using a mixture of ridicule and exasperation. It didn't work; Lizzie stuck to her story. Consider the following exchange:

Q. (Knowlton) "The first thing in preparation for your fishing trip the next Monday was to go to the loft of that barn to find some old sinkers to put on some hooks and lines that you had not then bought?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "I thought if I found no sinkers I would have to buy the sinkers when I bought the lines."

Q. (Knowlton) "You thought you would be saving something by hunting in the loft of the barn before you went to see whether you should need them or not?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "I thought I would find out whether there were any sinkers before I bought the lines. If there was I should not have to buy any sinkers."

Q. (Knowlton) "You began the collection of your fishing apparatus by searching for the sinkers in the barn?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Yes, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "You were searching in a box of old stuff in the loft of the barn?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Yes, sir; upstairs."

Q. (Knowlton) "That you had never looked at before?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "I had seen them."

Again:

Q. (Knowlton) "You were then, when you were in that hot loft, looking out of the window and eating three pears, feeling better, were you not, than you were in the morning when you could not eat any breakfast?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "I never eat any breakfast."

Q. (Knowlton) "You did not answer my question, and you will, if I have to put it all day. Were you then when you were eating those three pears in that hot loft, looking out of that closed window, feeling better than you were in the morning when you ate no breakfast?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "I was feeling well enough to eat the pears."

At that point, Knowlton wisely changed his approach. Lizzie testified that she last saw her stepmother at about 9 A.M.; Abby was dusting in the dining room. In discussing their conversation, Lizzie introduced her story about the note:

Q. (Knowlton) "Had you any knowledge of [Abby] going out of the house?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "She told me she had a note, somebody was sick, and said she was going to get the dinner on the way and asked me what I wanted for dinner."

Q. (Knowlton) "Did she tell you where she was going?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "No, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "Did she tell you who the note was from?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "No, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "Did you ever see the note?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "No, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "Do you know where it is now?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "No, sir."

Q. (Knowlton) "She said she was going out that morning?"

A. (Lizzie Borden) "Yes, sir."

That was what Lizzie had to say about the note under oath. Earlier, she said it was delivered by "a boy".

One fragment of Lizzie's testimony that always baffled me was her statement that any blood spots on her undergarments could have come from flea bites. She went on to say that she told the police officers she had fleas. It turned out that Lizzie was using a Victorian euphemism; a woman going through a menstrual period, like Lizzie, was said to "have fleas".

Lizzie's Arrest

Lizzie completed her inquest testimony at 4 P.M. on Thursday, August 11. Three hours later she was arrested, charged with the murder of her father, Andrew Borden. For some curious reason, the warrant did not mention Abby Borden. It did, however, specify that the murder weapon was a hatchet. This must have disappointed several self-appointed experts who informed the police that Lizzie probably used a flatiron. (She was ironing handkerchiefs that morning and "everyone knows" that blood can be more easily washed off an iron than a hatchet).

There is some disagreement as to how Lizzie reacted to her arrest. A reporter for the New York Times said she took the news with surprising calmness. Yet, according to an account in the New York Herald, she , "fell into a fit of abject and pitiable terror." Take your pick!

At 9 A.M. on Friday, August 12, Lizzie Borden, accompanied by her lawyer, Andrew Jennings, appeared before Judge Blaisdell to answer the charge against her. When the clerk asked how she pleaded, she answered firmly, "not guilty." Blaisdell then scheduled a preliminary hearing for August 22, where he would preside as he had at the inquest. Jennings objected to this arrangement, saying among other things that:

"It is beyond human nature to suppose that Your Honor could have heard all the evidence at the inquest and not be prejudiced. I submit that Your Honor is acting in a double capacity and therefore you cannot be unbiased. This takes away from my client her constitutional right to be heard before a court of unprejudiced opinion."

The objection was overruled.

That same afternoon, Lizzie Borden was taken by train to the Bristol County jail at Taunton, fifteen miles north of Fall River. At Somerset, the train stopped briefly. On the platform there were about a dozen young women, one of whom somehow recognized Lizzie and cried out, "There she is; there's the murderess." All the women ran over to the car where she was sitting and peered in at her. According to a reporter on the train, Lizzie never moved a muscle. As Marshal Hilliard pointed out, "She is a remarkable woman possessed of wonderful power of fortitude." Lizzie's friend, Reverend Buck, put it more positively, "Her calmness is the calmness of innocence."

It was generally supposed that Lizzie would stay at the Taunton jail only until the preliminary hearing which, like the inquest, was to be held in Fall River. In practice, the jail was her "home" for the better part of ten months. Her cell was a small one, furnished with the bare necessities; a bed, a chair and a washbowl. She spent much if not most of her waking hours reading. Included were novels by Charles Dickens, religious tracts, and just about anything she could get her hands on. There was one exception; by her own request she did not receive a daily newspaper and so did not know what the press was saying about her. Lizzie's sister Emma frequently visited as did her minister and other members of the Central Congregational Church of Fall River.

The keeper of the Taunton jail was Sheriff Andrew Wright, who was at one time chief of police in Fall River. When he and his wife lived in Fall River, Lizzie was a little girl; she frequently came to their home to play with their daughter. Perhaps that explains why she was sometimes given special privileges at the jail. In particular, she was allowed to order meals sent in from a local hotel to supplement the meager and unappetizing prison fare. (A typical breakfast served to the inmates consisted of fish hash and bread; all things considered I might have preferred cold mutton and johnny cakes).

When Lizzie Borden was arrested, the predominant reaction in Fall River was one of relief. There was an almost palpable relaxation of the tension that had gripped the city for a week. No longer did people worry about a homicidal maniac invading their homes as he had the Borden house. The double murder was not, after all, a motiveless crime; instead it was an "inside job". In a weird kind of way, people wanted to believe that Lizzie was guilty. District Attorney Knowlton got letters demanding her conviction. Perhaps the most outspoken contained the following admonition:

"Do your Duty without fear. The whole world thinks Elizabeth Borden murdered her poor old Father and Stepmother. Elizabeth Borden chopped up those two poor old people, all for money, and spite, and Hate. She is a Double Murderer and should be hung twice. She committed Two murders and chopped up her poor old Father and his Wife in cold blood. She is a wicked wretch, a vile, cruel murderer. She is a child of the Devil. Do not let her off. She will chop up some one else if you let her off. Do your Duty and Hang her twice."

On the other hand, there were people who believed strongly in Lizzie's innocence. Someone sent Knowlton an abusive handwritten note:

"[You are a] Dirty Coward who attempts to destroy the reputation of an innocent woman. [Your face] should adorn the rogue's gallery instead of holding office in this commonwealth."

Lizzie's inquest testimony would haunt her for the rest of her life. Almost certainly it was directly responsible for her arrest. Her inconsistencies, both with her own prior statements and the testimony of others, persuaded many people that she was guilty.

Perhaps Lizzie's faltering performance at the inquest was caused by the morphine Dr. Bowen prescribed to calm her nerves. More likely, it was a result of District Attorney Knowlton's ferocious attack on her credibility. Nothing in Lizzie Borden's sheltered existence prior to August 4, 1892, prepared her for this type of confrontation. Toward Knowlton she felt fear bordering on terror. Never again would Lizzie Borden appear on the witness stand. One interrogation by a relentless prosecutor was enough for a lifetime.