Читать книгу The Big Man - William McIlvanney - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

‘Look,’ one of the three boys in a field said as the white Mercedes slid, silenced by distance, in and out of view along the road. The boy had bright red hair which the teachers at his school had learned to dread appearing in their classrooms for it meant mischief, a spark of social arson.

‘A shark. A great white.’

His two companions looked where his finger pointed and caught the melodrama of the gesture. The one who was holding the greyhound said, ‘Kill, Craigie Boy, kill,’ and the big, brindled dog barked and lolloped on the leash. The red-haired boy started imitating the theme music from the film Jaws and the other two joined in. Their voices hurried to crescendo as they saw the car disappearing over the top of a hill.

The car moved on under a sky where some cloud-racks looked like canyons leading to infinity and others were dissolving islands. There, floating in the air, were the dreams of some mad architect, wild, fantasticated structures that darkness would soon demolish. They were of a variousness you couldn’t number.

‘Five,’ the biggest man in the car said. He was called Billy Fleming. He spoke without expression. His face looked mean enough to grudge giving away a reaction.

There was no immediate response from the other two. A boring journey had made reactions in the car sluggish. Each was in his own thoughts like a sleeping-bag.

‘Five what?’ the driver said after a time, thinking it wouldn’t be long until he needed the lights. His name was Eddie Foley.

‘Dead crows. That’s five Ah’ve counted. Two on the road. Three at the side of it. They should take out insurance. What are they? Deaf or daft? Always pickin’ on passin’ cars.’

They came to a village called Blackbrae. The council houses at the edge of it, badly weathered but with well-kept gardens, led on to private houses lined briefly along each side of the street. These sat slightly further off the road, solidly and unelaborately built. Designed less to please the eye than persuade it to look elsewhere, they were squat fortresses of privacy. It was hard to imagine much vanity in possessing them. Yet the meticulous paintwork or the hanging plant in a doorway or the coach-lamp on the wall beside a recently added porch suggested a pleased possessiveness. The names, too, had a cosy complacency. There was Niaroo and Dunromin and, incredibly enough, Nirvana. A passer-by might have wondered at how modest the dreams had been that had found their fulfilment here.

The street turned left towards a hill that climbed back into the countryside. Changing gears, Eddie Foley hesitated in neutral and gently braked.

‘I think we’re lost,’ he said. ‘Did Fast Frankie mention this place?’

‘Has anybody ever?’ Billy Fleming asked from the back seat.

‘Ask,’ the third man in the car said.

At the top of the hill a small obelisk with a railing round it was outlined against the sky. On a bench beside it two men sat and a third stood with his foot on the bench, nodding towards the others. In the hollow of the hill, where the car was, there were mainly closed shops. A building that claimed to have been a garage was empty and derelict. Asphalt patches in front of it might have been where the pumps were. The owner’s name was a conundrum of missing letters – Mac- something. The only indication of life between them and the men at the top of the hill was outside the Mayfair Café. The name was carried on a white electric sign, not yet lit, projecting from the wall. The letters declaring the name were slightly smaller than those beneath, which announced a brand of cigarettes, so that it was as if the identity of this place, obviously a focal point of the village, was dependent on a company that had no connections here.

Five teenagers were standing outside the café, two boys and three girls. One of the boys, the smaller one, was doing an intricate but very contained soft-shoe shuffle with his hands out, palms towards his friends. He was wearing jeans and a black tee-shirt, sleeves rolled up to show his biceps. The others were laughing. Eddie Foley put the car in gear, eased along the kerb towards them and stopped. He loosened his seat-belt, leaned across the empty passenger seat and pressed a button. The window hummed down slowly enough for the group on the pavement to become aware of it. The dancer gave his friends a theatrical display of amazement and leaned down towards the open window.

‘That was terrific, mister,’ he said. ‘Could ye do it again?’

‘Thornbank?’ Eddie Foley said.

‘Naw,’ the dancer said. ‘My name’s Wilson.’

‘I’m looking for Thornbank.’

‘If ye give us a lift, we’ll take ye.’

‘It’s either right or left or straight on,’ one of the girls said.

The wit of it crippled the others with laughter. They leaned helplessly on one another and the girl herself had to admit how good it was, her pink hair coming to rest on the shoulder of the taller boy. Eddie Foley pressed the button and the window went up as the car moved off.

‘The natives don’t seem very friendly,’ he said.

‘Maybe we shoulda brought some coloured beads,’ Billy Fleming said.

‘Children,’ the third man said, ‘grow up into shites quicker every year.’

He was a small man with thinning hair. He wore nice rings and he had grey eyes that were so cold the flecks in them could have been crushed ice. He was Matt Mason.

Eddie Foley took the car up the hill and stopped across the road from the three men at the bench. He got out of the car and went over to them. Two of them looked about forty. The one with his foot on the bench must have been over sixty. He was the one who spoke.

‘Yes, sir. Can we help ye?’

‘I’m looking for Thornbank.’

‘Ye’re well out yer way here,’ one of the men on the bench said. ‘Where ye comin’ from?’

‘Glasgow.’

‘Ye woulda been better holding the dual carriageway tae outside Ayr,’ the third man said.

‘Ye’re wrong, Rab,’ the older man said.

In the car Matt Mason and Billy Fleming watched but couldn’t hear what was being said. They saw the conspiratorial noddings of the three men before they formed into an advisory committee for Eddie. They saw the pointing gestures, one of the seated men standing up and doing an elaborate mime of directions. They saw Eddie nodding towards the obelisk. In the soft light of late evening the scene had a simple dignity, four men silhouetted against the vastness of the sky in a mime of small preoccupations.

‘What’s he doing?’ Matt Mason said. ‘Getting a history of the place?’

Eddie came back across and got in the car. He waved as he drove away and the three men waved back.

‘Ah know where we’re goin’ now,’ he said. ‘They were nice men.’

‘We’re not here to socialise,’ Matt Mason said.

‘That was a monument they were sittin’ beside. To the men from the village. Died in the First and Second World Wars. One of them was holdin’ somethin’. Some kinda tool. Ah hadny a clue what it was for. Imagine that. Ye would think ye would know what it was for. Ah mean, this isny Mars.’

‘Is it not?’ Billy Fleming said and glanced across at Matt Mason for confirmation of his sneer.

Matt Mason looked back at him and then looked down at Billy Fleming’s trainer shoe resting on the back of the driving seat. The foot came off the seat and rested on the floor. Billy Fleming checked that the fawn upholstery wasn’t marked.

The black and white trainer shoes were part of a strange ensemble. They were topped by jeans and then a black polo-neck cashmere sweater, over which he wore an expensive-looking grey mohair jacket. It gave him an appearance as dual as a centaur. Above, he was a kind of sophistication; below, he was all roughness and readiness to scuffle. The face linked the two: a bland superciliousness overlaid features that bore the traces of impromptu readjustment.

‘Ah was goin’ to ask what it was,’ Eddie said. That tool thing. But Ah felt such a mug, Ah didn’t bother.’

Neither of the other two responded, and Eddie pursued the subject in his mind. The strange object the man had held and the solemnity in the darkening air of those names carved on the obelisk – names he imagined would mean much to most people in the village – had combined to make him feel what strangers they were here, the carelessness of their coming, rough and sudden as a raiding-party. He had sensed in the talk with them a formed and complicated life about the place, a strong awareness among them of who they were, mysterious yet coherent with a coherence he couldn’t understand. It was an uncomfortable feeling, as if he were a hick from the city.

The atmosphere in the car intensified the feeling. They seemed to be travelling within where they had come from. The plush upholstery appeared foreign to the places they were passing through. With the exception of Billy’s jeans and trainers, their city clothes would have looked out of place outside, as if they had come dressed for the wrong event. The smoke from Matt Mason’s cigar surrounded them, cocooning them in themselves.

Negotiating the winding ways, Eddie felt himself subject to the unexpected nature of events, the way an outcrop of land suddenly threw the road to the left, the recalcitrance of a hill. These roads were less invention than discovery. They weren’t merely asphalt conveyor belts along which sealed capsules fired people from one identity to the next as if they had dematerialised in the one place and rematerialised in the other. These roads made you notice them, rushed trees towards you, flung them over your shoulder, laid out a valley, flicked a flight of birds into your vision. They made Eddie aware of a countryside his ignorance of which was beginning to oppress him with questions that baffled him. What kind of people would live in that isolated farm on the hill? What kind of trees were they?

‘Flowers,’ he said suddenly. ‘The names of flowers. Ah always wanted to know a bit about that. Ah canny tell one from another. That’s true. Ah’ve got bother tellin’ a daisy from a dandelion.’

‘Six,’ Billy Fleming said. ‘That was a cracker. Only thing that wasn’t mashed tae a pulp was its beak. Definitely the prize-winner.’

Eddie became aware of Matt Mason’s silence. He had learned to be wary of that silence. He decided to push his misgivings aside. He was here on a job for Matt Mason. It wouldn’t do to confuse his loyalties.

‘Fast Frankie’s not too hot on the directions,’ he said, reidentifying himself with the other two and their purposes. ‘Ah hope his information’s more reliable. Ye think the big man’s what he says he is?’

‘Frankie thinks he is,’ Matt Mason said, and remembered the time in the Old Scotia with Frankie talking.

Fast Frankie White was a handsome quick-eyed man with a smile as selective as a roller-towel. He had been born in Thornbank – so he should know what he was talking about – and had left it by way of petty theft. He still went back there from time to time, usually when he was in trouble, to wrap his widowed mother’s house round him like a bandage. He often said more than it was wise to believe but in the Old Scotia he had sounded convincing.

‘Okay. Ye’ve got a decision to make. Fast. Ah know. But Ah’m tellin’ ye. He’s yer man. No question. Ah’ve known him for years. He’s the man ye’re lookin’ for. And easily worked. A big, straight man. Straight as a die. That’s what ye need, isn’t it? Honesty’s the best raw material in the world. Especially the poor kind. He’s gold for you, Matt. A rough nugget, certainly. But you could shape him into anything ye want. What’s he got in Thornbank? What’s anybody got in Thornbank? He’s on his uppers. Been idle for months. Used to work in the pits. How many pits are there now? Was working up at Sullom Voe for a while. But the wife didn’t fancy the separation. See, that’s the secret. That’s how you’re goin’ to get him. He’s a great family man. An’ what’s he providin’ for his wife and weans? You can offer him a way to do that. He’ll bite, Matt. Ah’m tellin’ ye, he’ll bite. And once he’s got a taste, ye’ll have him for good. An’ all they’re goin’ to be able to do . . . With this man? Come on!’

Matt Mason remembered the image of Frankie with his arms crossed in front of him. He had swung his arms apart, hands up, with the brightness and activity of the pub behind him. It was the gesture of surrender we’re supposed to make when faced with a gun.

‘Different class,’ Frankie White had said.

In the almost dark a pit-bing loomed on their right. It was overgrown with rough grass, a man-made parody of a hill. The despoliation of the countryside around them made them feel more at home. Inside the car they enlivened into a conversation.

‘Not long now,’ Eddie said. ‘If he’s that good, what’s he doin’ living in a place like this?’

Matt Mason smiled to himself.

‘Maybe he likes the quiet life.’

‘He better learn not to like it then,’ Billy Fleming said.

‘We’ll find out how good he is,’ Matt Mason said.

Eddie put the lights on.

‘He’ll maybe not come,’ he said.

‘Same time every Sunday, Frankie says,’ Matt Mason said.

‘The Red Lion,’ Eddie said.

‘Funny name for a hotel,’ Billy Fleming said. ‘Ye wonder who thinks them up.’

The arrival of darkness had welded them into a group with a unified purpose. The variousness of the countryside was obliterated. It could have been anywhere. There was only the familiar interior of the car and the headlights blow-torching their own path through the night. Matt Mason looked at his watch.

‘We’ll be in good time,’ he said. He looked across at Billy Fleming. ‘You ready?’

‘Born ready.’

In the dim light he looked as if he might be telling the truth. The big shoulders seemed to be filling most of the back seat of the car. The face, planing intermittently out of obscurity, looked relentless as a statue. He carefully took off his wrist-watch and wrapped it in a handkerchief and put it in his jacket pocket.

Everybody knows and doesn’t know a Thornbank. It’s one of those places you’ve driven through and never been there. It occurs in conversations like parentheses. ‘It took us four hours to get there,’ someone says, ‘and the kids were fractious after two miles. We went the Thornbank road.’ Hearing it mentioned, outsiders who know of it may still have to think briefly to relocate it. It’s the kind of place people get a fix on by association with the nearest big town, knowing it as a lost suburb of somewhere else.

In Thornbank’s case the big town is Graithnock, the industrial hardness of which dominates the soft farmland of the Ayrshire countryside around it. Graithnock is a town friendly and rough, like a brickie’s handshake. It is built above rich coalfields which have long since run out, ominously.

By the time the coal was gone, Graithnock hardly noticed because it had other things to do: there was whisky-distilling and heavy engineering and the shoe factory and later the making of farm machinery. But the shoe factory closed and the world-famous engineering plant was bought by Americans and mysteriously run down and the making of farm machinery was transferred to France and the distillery didn’t seem to be doing so well.

Not much in the way of coherent explanation filtered as far as the streets. At meetings and on television men who looked as if they had taken lessons in sincerity read from the book of economic verbiage, the way priests used to dispense the Bible in Latin to the illiterate. All the workers understood was that there were dark and uncontrollable forces to which everyone was subject, and some were more subject than others. When the haphazardly organised industrial action failed, they took their redundancy money and some went on holiday to Spain and some drank too much for a while and they all felt the town turn sour on itself around them.

For, like John Henry, Graithnock had been born to work. It was what it knew how to do. It was the achievement it threw back into the face of its own bleakness. It liked its pleasures, and some of them were rough, but the joy of them was that they had been earned. The men who had thronged its pubs in its heyday were noisy and sometimes crude and sometimes violent, but they knew they were stealing from nobody. Every laugh had been paid in sweat. The man who had embarrassed himself in drink the night before would turn up next morning where the job was and work like a gang of piece-work navvies.

When there was nowhere for him to turn up, what could he do? Like so many of the towns of the industrial West of Scotland, Graithnock had offered little but the means to work. It had exemplified the assumption that working men are workers. Let them work. In the meantime, other people could get on with the higher things, what they liked to call ‘culture’. At the same time, the workers had made a culture of their own. It was raw. It was sentimental songs at spontaneous parties, half-remembered poems that were admitted into no academic canon of excellence, anecdotes of doubtful social taste, wild and surrealistic turns of phrase, bizarre imaginings that made Don Quixote look like a bank clerk, a love of whatever happened without hypocrisy. In Graithnock that secondary culture had been predominant. While in the local theatre successive drama companies died in ways that J. B. Priestley and Agatha Christie and Emlyn Williams never intended, the pub-talk flourished, the stories were oral novels and the songs would have burst Beethoven’s eardrums if he hadn’t already been deaf. But it was all dependent on money. Even pitch-and-toss requires two pennies.

When the money went, Graithnock turned funny but not so you would laugh. It had always had a talent for violence and that violence had always had its mean and uglier manifestations. Besides the stand-up fights between disgruntled men, there had been the knives and the bottles and the beatings of women. The difference now was that contempt for such behaviour was less virulent and less widespread. Something like honour, something as difficult to define and as difficult to live decently without, had gone from a lot of people’s sense of themselves. Sudden treachery in fights had assumed the status of a modern martial art, rendering bravery and strength and speed and endurance as outmoded as a crossbow. An old woman could be mugged in a park, an old man tied and tortured in his home for the sake of a few pounds, five boys could beat up a sixth, a girl be raped because she was alone, the houses of the poor be broken into as if they had been mansions. This was not an epidemic. Few people were capable of these actions but those who weren’t were also significantly less capable of a justly held condemnation. That instinctive moral strength that had for so long kept the financial instability of working-class life still humanly habitable, like a tent pitched on a clifftop but with guy-ropes of high-tensile steel, had surely weakened.

Theorists rode in from time to time from their outposts of specialisation, bearing news that was supposed to make all clear. Television was setting bad examples. Society had become materialistic. Schools had abdicated authority. The hydrogen bomb was everyone’s neurosis. What was certain was that Graithnock didn’t know itself as clearly any more.

Even physically, the town had been not so much changed as disfigured. Never a handsome place, it had had at its centre some fine old buildings that had some history. They were demolished and where they had been rose a kind of monumental slum they called a shopping precinct. As a facelift that has failed leaves someone looking out from nobody’s face in particular so Graithnock had become a kind of nowhere fixed in stone. The most characteristic denizens of its new precinct, like the ghosts of industry past, were alcoholics and down-and-outs.

Thornbank, as the child copes with the parents’ problems, was suffering too. A lot of the redundancies from Graithnock had come here. But there were apparent differences. The same television programmes reached Thornbank, the schools had much the same problems, the hydrogen bomb had been heard of there too. But a stronger and continuing sense of identity remained. One reason was, perhaps, its size. It was a place where people vaguely felt they knew nearly everybody else. This absence of anonymity meant that in Thornbank they were often, paradoxically, more tolerant of nonconformism than people might have been in bigger places. Difference was likely to become eccentricity before it could develop anti-social tendencies.

There was in the small town, for example, a group of punks, working-class schismatics who had seceded from their parents’ acceptance of middle-class conventions. Their changing hair colours, purples, greens and mauves, their earrings that were improvised from various objects, their clothes that looked as if they were acting in several plays at once, all of them bad, were not admired. But they were mainly confronted with a slightly embarrassed tolerance, like a horrendous case of acne. Of Big Andy, who led a local punk group called Animal Farm and whose Mohican haircut stood six-feet-three above the ground and seemed to change colour with his mood, it was often mentioned in mitigation that his Uncle Jimmy had been a terrible fancy dresser. Genes, the implication was, were not to be denied.

This communal sense of identity found its apotheosis in a few local people. Thornbank knew itself most strongly through them. They were as fixed as landmarks in the popular consciousness. If two expatriates from that little town had been talking and one of them mentioned the name of one of that handful of people, no further elaboration would have been necessary. They would have known themselves twinned. Those names were worn by Thornbank like an unofficial coat of arms. These were people to whom no civic monuments would ever be erected. They were too maverick for that. Part of their quality was precisely that they had never courted acceptance, refused to make a career of what they were. They were simply, and with an innocent kind of defiance, themselves.

There was Mary Barclay. She was in her seventies and fragile as bell metal. They called her Mary the Communist and although nearly everyone in the town thought Communism something historically discredited, a bit like thalidomide, the epithet as it applied to her carried no opprobrium. It wasn’t that the term defined her so much as she qualified the term. She was Marx’s witness for the defence in Thornbank. Her life had been an unsanctimonious expression of concern for others. While helping everybody she could, she had also helped herself without inhibition to what in life injured nobody else. She had lived with three men and married none. She had buried the one who died on her, decently, and been loving to her two daughters who, as far as anybody knew, had never reproached her. She was who she was and you could take it or leave it, but you would have been a fool to leave it.

There was Davie Dykes, known as Davie the Deaver, which meant if you listened long enough he would talk you deaf. But it was mainly good talk. He told elaborate and highly inventive lies. Each day he reconstructed his own genealogy. His ancestry was legion. At sixty, he still refused to be circumscribed by his circumstances. Here was just a route to anywhere.

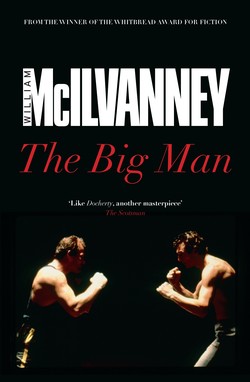

There was Dan Scoular. His place in the local pantheon was more mysterious. He was young for such elevation, thirty-three. His most frequently commented on talent was a simple one. He could knock people unconscious very quickly, frequently with one punch. It wasn’t easy to see why such a minimal ability and of such limited application should have earned him so much status. It was true that Thornbank, like a lot of small places which may feel themselves rendered insignificant by the much-publicised wonders of the bigger world, had a legendising affection for anything local that was in any way remarkable. There were those who kept a Thornbank version of The Guinness Book of Records: the heaviest child that had been born here, the fastest runner in the town, the man who had been arrested most for breach of the peace. But that hardly explained that converging ambience of something achieved and possibilities to come in which Dan Scoular moved for them.

Their name for him was, perhaps, a clue. They called him ‘the big man’. It was an expression used of other men in the town, of course. But if the words were used out of any explanatory context, they meant Dan Scoular. Though he was six-feet-one, the implications were more than physical. They meant stature in some less definable sense. They had to do with his being, they suspected, in some way more inviolate than themselves, more autonomously himself. They had to do, perhaps most importantly, with the generosity and ease with which they felt he inhabited what was special about himself, his refusal to abuse a gift or turn it unfairly to his own advantage. For he could be quietly kind.

Yet the image the people of Thornbank had of him was false. They had mythologised his past and falsified his present. They had made him over into something that they wanted him to be. ‘He’s never picked on anybody in his life,’ was a remark so often made in Thornbank in relation to Dan Scoular that it had acquired a seeming immutability, like a rubric carved on a plinth. It was a lie. It conveniently excised from public recollection a few years of his youth when his prodigious capacity for aggression had functioned on his whim and no casual encounter in a pub or at a dance was safe from its explosive arbitrariness.

‘He’s never looked at another woman,’ the oral history said. Perhaps they should have asked his wife Betty, an attractive and spirited woman, about that.

‘He’s his own man, that one,’ was a refrain that no one contradicted. But it was more an appearance than a fact. Dan Scoular didn’t know who he was. He felt daily that people were giving him back a sense of him that in no way matched what was going on. His statue didn’t fit.

But what they needed him to be they had partly accustomed him to pretend to be. He meant something in the life of Thornbank and he tried to live inside that meaning as best he could, like a somnambulist pacing out someone else’s dream. They looked to him to confirm that things were more or less all right. If he was as he had been, living along among them, coping quietly, things couldn’t be that bad. Like the Mount Parish Church clock, he was a familiar fixture by which they checked how things were going. Like that notoriously erratic timepiece, he was misleading. Thornbank was in no better state than Graithnock. It was just less aware of its condition. Dan Scoular was becoming desperately aware of his.

Failing marriages are haunted. They have lost the will for mastery of the present and the future looms as re-enactment of the past. Every day is full of the ghosts of other days, most of them emitting unassuaged rancour at small and large betrayals. New possibilities drown in their lamentations.

That Sunday Betty had wakened first. She heard the voices of the boys downstairs, beginning the statutory quarrel. The sound pulled at her mind like a tether: did you imagine your thoughts could wander off for a moment by themselves? She wondered briefly if their noise had wakened her or if they had been waiting poised like demonic actors, cued into automatic conflict by her consciousness. She rose and put on her housecoat, careful not to waken Dan. It wasn’t something done out of consideration but because it postponed the time when they would have to talk. That was the first small, renewed betrayal, confirmation of where they had come. It was a message in code, delivered to him though he was asleep. He would understand it when he woke.

As she crossed to find her slippers under the dressing-table, the noise downstairs subsided to a civilised murmur and she paused, having lost her motive for getting out of bed. She knelt in front of the mirror, picked up the hairbrush and made a couple of passes at her hair. She noticed herself in the glass and stopped. She was aware of the dishevelled heap of Dan’s body on the bed, reflected from behind her. It was perhaps his humped image beside her face which triggered the memory.

‘And I’d also like to thank my own parents. Apart from the obvious trick they pulled in bringing me about. Although I have it on very good authority that Mrs Davidson isn’t too sure that’s how it happened. She still thinks I fell off the back of a lorry.’ (There was the kind of laughter people laugh at public events, as if a joke were a charity auction and they want to be seen to be bidding.) ‘But apart from that. I’d like to thank my parents for what they did as soon as they realised Betty and me were getting married. They stopped taking any money from me for my keep. It’s helped us a lot. They decided we needed all the money we could get to set up our own house. We’d both like to thank them for that. Mind you, I think they were beginning to get panicky towards the end there. I think they thought we were gonny have a seven-year engagement. Ah mean. I think they feel they’re not so much losing a son. They’re losing a liability. For the past year or so, if we’d been a Red Indian family . . .’ (titters greeting amazing concept) ‘. . . where they’ve got funny names like Running Bear and Running Water. The only appropriate one for me would’ve been Running Sore.’ (Total surrender to helpless mirth, corpulent uncles having cardiac arrests and aunties squawking like parakeets getting plucked alive.) ‘Anyway, my wife and I . . .’ (Stamping of feet, whistling, applause.)

It had been something like that. That was how Betty remembered it. Apart from having been there at the time (although she sometimes wondered if it was really herself who had been there), she had, the day before, found the piece of paper on which Dan had made the notes for his speech. She had remembered how much he had wanted to get that speech right, his nervous determination. He knew her parents’ disapproval of him and the superciliousness of some of her aunts and uncles. He had felt like the champion of his ‘side’, not about to let them down, ready to demonstrate that he could string a few words together. He had made the best speech of the wedding and then almost undone his success by quarrelling in the lavatory with one of her cousins, who had expressed amazement at how well Dan had spoken. She heard later from an outraged uncle that Dan’s immediate response had been, ‘I’m not amazed at your amazement. The next time you get anything right’ll be your first.’

Betty had been looking for the insurance policy for the house contents the day before when she had come across that folded, scuffed and fading piece of paper. She had opened it out carelessly and it had hit her like a jack-in-the-box with a knife. She had read it slowly, her stomach feeling slightly mushy with guilt, for in the words she sensed a confident assertion that was like a contract they had both failed to keep. She had remembered the moment when those words were said.

She remembered that moment now, as she knelt at her dressing-table mirror: ‘My wife and I . . .’ Staring at herself, she saw that other face, as if her past were a helpless spirit hovering over her present. In retrospect, the brocade wedding-dress and veil seemed somehow preposterous, a grotesquely ornamental, weird costume for a part nobody knew how to play. They gave you a few lines of ritual dialogue that came from God knows what lexicon of antiquated male prejudice and the rest of your life was endless improvisation, entirely up to the two of you.

She saw Dan standing making his speech, confidently belying his nervousness, herself sitting in demure white, the audience looking on, seeing what they wanted to see. As she remembered it, they both seemed to her, in a simple and not very dramatic way, sacrificial. She remembered a joke she had heard somewhere about married people, comparing them to swimmers in freezing water, shouting, ‘Come on in. The water’s great.’ ‘My wife and I . . .’ It didn’t seem to her to be imagination that she could remember a slightly derisive tone to some of the applause.

Watching her face without make-up, she remembered an expression that had fascinated her as a girl. She had always applied it to herself in the third person, making herself in her mind into the woman she imagined she might become. ‘She put on her face.’ The statement now seemed to her utterly apposite, an ambition that had closed around her like a trap. She put on her face. The face she had remembered in its veil was somehow lost, hadn’t merely changed.

These days she built an alternative in front of her mirror, created a role as self-consciously as an actress might with stage make-up: the wife. In some way that threatened the convincingness of her performance, it wasn’t truly her. Staring at herself, she vaguely felt that the accretions of experience she saw there weren’t an expression of her at all. They were a denial of some basic potential in her. Perhaps what we see in older people, she thought, are the complex stances and tics they have developed in response to the reactions to their original selves – not them so much as the camouflage they have had to become.

‘Leave it alone!’ Raymond shouted. ‘Or you’re gettin’ battered.’

As Betty straightened up, she heard a knee crack like a reminder of human frailty, a warning that she had better try to realise herself before it was too late. But the awareness was smothered at birth. She put on her slippers and they might as well have been bindings for her feet, so much they hobbled her to the day’s limitations. By the time she reached the bottom of the stairs, she had become ‘the mother’.

Raymond and young Danny were quarrelling over the pack of cards. Her arrival encouraged them to push their respective attitudes towards caricature. Raymond became innocently preoccupied in laying out the cards, his monkish dedication astonished at her arrival. ‘Oh, hello, Mum.’ Danny’s arms went out in outrage at the cruelty of man’s ways. ‘Mum!’ She felt she couldn’t face their trivial intensity at this time of the day. But Danny jumped up and danced before her eyes like a midge with messianic delusions (Those who are not for me are against me’).

‘Mum! He’s playin’ patience!’

‘Shurrup. So what?’ Raymond said.

‘Two canny play patience. Ya bam!’

‘You said you didn’t want to play.’ Raymond was now using carefully formal English, showing his mother how calm he was, how full of rectitude.

‘Ah said Ah didn’t want to play whist. But there’s other games.’

‘That’s right. Patience.’

‘Ah said Ah would play rummy.’

‘I’m not playin’ rummy. You don’t play right. You don’t even know the rules. You make a run outa clubs and spades and everything. You’re daft.’

Danny kicked away Raymond’s line of cards and Raymond lunged to hit him and Betty screamed, ‘Raymond! The two of you! Shut up! For God’s sake, shut your mouths!’ They both looked at her in a shocked way, as if they had just discovered that their mother was mad. Her own next remark made Betty think they might be right.

‘What’ve you had to eat, the two of you?’ she asked and couldn’t herself see how that related to the problem.

‘We had flakes,’ Danny said in passing. ‘Ye know what he did, Mum? He stopped playin’ because Ah was winnin’. Ye did so!’

‘Did not.’

‘Did sot.’

‘Not.’

‘Sot.’

‘Not, not, not.’

‘Sot, sot, sot, sot, sot. Sot, sot. Sot, sot, sot –’

‘Danny! Stop! Stop, Danny!’

In the silence she gathered up the cards and put them on the mantelpiece.

‘Aw, Mum!’ from Raymond.

She resentfully made them a breakfast of sausage and egg and toast, salving her rebellious conscience by making them lay the table. She tried not to let her affections take sides. But Raymond was so unfairly arrogant, playing his age advantage against Danny. He was thirteen against ten and he used those three years as a brutal birthright. His darkness of hair seemed to her for the moment sinister. Danny, still fair like herself, seemed an aggressed-on innocent, a small boy who sometimes gave the heart-wrenching impression that life was for him like jaywalking at Le Mans. She had a weakness for his passionate desire for justice, even when it was totally misguided.

While she fed them, she remembered an incident last year. She and Dan had been sitting in the house when Danny had rushed in from playing football in the street outside. His cheeks were florid from exertion and his eyes flamed with intensity.

‘Dad! Dad!’ he had been calling from the outside door.

He arrived in the room like the bearer of the news the world had been waiting for.

‘Dad, Dad! Ah told the boys you would know the answer.’

Dan had glanced up from his paper.

‘Twenty-two,’ he said.

‘Naw, naw. Listen, Dad. Andrew got hit in the face wi’ the ball.’

Dan looked at her and rolled his eyes.

‘Hit in the face wi’ the ball!’ Danny said.

‘In the face,’ Dan said. ‘With the ball. Correct.’

‘All right. He was goin’ to tackle Michael. And Michael lashed it. He really thumped it. An’ it hit Andrew right in the face. Full force.’

‘Amazin’,’ Dan said.

‘Naw. But listen, Dad. Is it a foul?’

Dan started to laugh.

‘What d’ye mean?’

‘Is it a foul?’

‘How can it be a foul?’

‘But it hit him right in the face!’

‘Danny! It’s not a foul. Because the ball hits somebody in the face. It’s mebbe an accident. But it’s not a foul.’

Betty remembered Danny’s disappointment and then the hope that rekindled his eyes, the counsel for the defence who has found the incontrovertible point of law.

‘But, Dad,’ he said. ‘Andrew’s cryin’. He’s really roarin’.’

While Dan explained that tears didn’t make a foul, Betty thought she had glimpsed the core of Danny and remembered why she loved him so much. He believed that circumstances had to yield to feeling. He was such a lover that he couldn’t understand why the deepest feeling didn’t make the rules. As Danny trailed disconsolately back out the house to announce the bad news from the adult world, Betty felt a compassion for him that was out of all proportion to a football match.

It was perhaps that memory that determined how she would decide when Raymond picked up the cards from the mantelpiece as soon as he had finished eating. He was about to play patience again.

‘Raymond,’ she said. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Ah’m goin’ to play at cards.’

‘With Danny?’

‘No way. Danny’s a diddy.’

The venom of it annoyed her.

‘No he’s not,’ she said. ‘You want to play, Danny?’

‘Uh-huh.’ Danny put his last piece of toast in his mouth and crossed towards Raymond. Raymond threw the cards on to the floor. Danny painstakingly picked them up.

‘Right, Raymond,’ Betty said. ‘You don’t want to play with Danny, you don’t want to play. But just make sure you leave him alone.’

She heard Dan coming downstairs as Raymond brushed past her. When she went into the kitchen, Dan was standing, wearing only a pair of old trousers and looking drowsily into a packet of cornflakes as if there was a message there he must decipher. His rumpled presence somehow provoked her and one of those familiar quarrels over nothing already hung in the air around them. The rules for such quarrels were that the cause of them should be irrelevant and that the venom they evoked should be out of all proportion. Raymond had exiled himself to the back green and she could hear him kicking a ball steadily against the wall of the house as if he was trying to tell her something. Danny was pretending to play with the cards that had caused the trouble but he had put the television on. Dan shook the cornflake packet and its contents rustled faintly. The sound made her grit her teeth.

‘Oh-ho,’ Dan said. ‘No cornflakes.’

He said it gently enough but it was audible.

There’s some in it. I can hear them,’ Betty said.

Dan pulled open the packet and held it towards her.

‘If ye’ve got a microscope, Ah’ll show ye them.’

‘You normally take cornflakes for your supper?’

‘It’s ten past ten.’

‘The money I’m getting, we’re lucky we’ve got bread.’

He crushed the packet with unnecessary force and put it in the bin.

‘Your period due?’ he said.

It was the remark that rendered any mediating sanity powerless to intervene, the unfair reprisal that escalated the conflict. Until then she would have been herself inclined to admit that he was the offended party to begin with, but his spite had wakened to the possibilities quickly enough and she was content that the war was on, both sides wheeling out their weaponry.

They traversed some familiar ground, littered with the dead of old campaigns. Her contempt was loud for his need to relate any recriminations of hers to the menstrual cycle, as if having a womb precluded having a mind. He touched again on how she made a crisis out of every casual conversation, saw deliberate attacks in accidental gestures. The structure of the day was set, an expression of the complex of devious failures and abandoned possibilities and secret chambers of hurt where their lost hopes lived alone.

The fact that they weren’t going anywhere that day seemed simple enough. But behind it lay a reminder that they had recently had to sell the second-hand car. Just staying in the house compounded her frustration at the way they had to live, his sense of how he was failing them. Lunch was communication through the boys.

When he took Raymond and Danny out the back to play with the ball in the afternoon, she sat indoors with her coffee, reading her own alternative text in the glossy magazine she leafed through. It was how she might have been living, somewhere among those advertisements. She wouldn’t have minded that but the text between adverts depressed her, suggested that perhaps the price was too high. The bright preoccupied tone, so full of blind assurance, was like a more intellectual version of her mother set in type.

She thought about her mother. Were daughters condemned to fulfil their mothers’ worst fears for them as punishment for disobedience? But then her mother’s fears for her had been so chameleon that they would have been able to fit in with whatever habitat Betty had chosen, found a niche there and been ready to feed on any stray passing thoughts of hers, as now. Protectively, Betty reminded herself of her mother’s desperately self-limiting philosophy, like a cage to keep her in. It was the cage she had kept herself in.

Her mother had known things with a certainty beyond the power of reason to refute. She had known that housework put off is housework doubled. She had known that you would see things differently when you were older. She had known that a girl shouldn’t cheapen herself, steam irons never get the job done properly, once a Catholic always a Catholic, educate a girl you educate a family, some men only want the one thing, if she had her life to live again she would do it differently, you’re only a virgin once, nobody needs to be out at two in the morning, they should hang them, the truth never hurt anyone, marry in haste, repent at leisure and Dan Scoular wasn’t good enough for her daughter.

She had also been a very good cook and baker and the house had always been tidy, very tidy, but Betty honestly couldn’t remember when her mother had touched her spontaneously. She could recall her mother kissing her goodnight but that was a ritual, something she had decided you were supposed to do, not an unrehearsed act of affection. When she thought of her mother, and she had often tried so hard to do it justly, she thought of that voice like a barking dog forbidding the world to come near her. She thought of One Thousand and One Nights of clichés, of a Scheherazade whose frenetic variety of repetitions was not a postponement of death but of life, a charm against the dread of coming alive.

And her father had fallen in love with that ability. She thought of the way he used to raise his eyebrows and shrug, as if in conspiracy with Betty’s outrage, but really – she had realised how many times since – in conspiracy with her mother. In return for those utterances neither of them could possibly believe, he was given his status, his small, imagined kingship of the house. Betty was, she had slowly and painfully come to realise, irrelevant here. A two-way charade was in progress. Nobody else knew the rules.

Dan Scoular had been an innocent intruder. She remembered them talking to her after his first time in the house, when he was gone. Quietness had been the first thing, her mother moving about and doing things only she could have imagined needed done, her father in soulful conclave with the gas-fire. They were talking to each other with silence and she was excluded, except insofar as she was meant to understand that she had somehow failed them. Their silence was hurt, deep shock which she was supposed to realise she was responsible for.

That night a lot of scattered misgivings about the way she and her parents lived had come together for her, and from them she had begun to make a kind of credo for herself. Her relationship with Dan had already given her an alternative sense of herself, an awareness of her own worth that contradicted her mother’s dismissive criticisms, which ranged from the way she dressed to her inability to cook. But the most painful forms those criticisms took were their trivial, momentary manifestations. It might be the way she had thrown down a magazine or the way she was sitting or a look she was supposed to have given. Her mother seemed capable of arranging endless ambushes in which Betty was taken by surprise and robbed of her self-esteem. Dan restored to her a more balanced sense of herself. His appreciation of her was like a constantly repeated present.

That night, after he had gone, that sense of herself remained with her. His absence had stayed stronger than their presence, had enabled her not to become a part of her parents’ strange ritual but to maintain her own perspective on it and, with a quiet dismay, understand what was really happening. Her mother had eventually stopped fussing around and sat down across the fire from her father.

The atmosphere was one with which she was familiar. Sometimes, coming in from a night out, she had been invited into the lounge to sit with her parents and their friends. The invitation was usually extended with an elaborately insistent generosity, a privilege self-consciously granted.

They all sat around with their drinks, playing a game Betty had decided to call pass-the-bromide. The reek of complacency in the room was as strong as formaldehyde. She used to wonder if they changed their smiles daily with the flowers. If anything strange were mentioned as having happened, the shock of it was quickly neutered to surprise by common consent.

The only displays of strong emotion she had seen among them took a careful stylised form and seemed triggered by a pre-determined set of values. What was happening outside the immediate range of their own lives was disarmed, could provide no trigger for deep feeling. Things like the rates, the iniquity of conveyancing or the shabbiness of modern workmanship were rich in potential for long, heartfelt diatribes.

Once she had watched a neighbour come apart slowly and with dignity in her parents’ lounge. She cried for several minutes, her mascara spiking the rims of her eyes. Betty’s mother had gone across to comfort the woman. The others looked on in sympathy. It would have made a moving scene in a silent film. But Betty had heard the sound-track. The woman was crying because her teenage son had taken to wearing his hair long and his clothes were casually shabby. Everybody in the room except Betty seemed to understand instantly the grief he had caused his mother, to share in her sorrow at the wantonness with which life inflicts its sufferings. There were murmured condolences, remarks about ‘no matter what you do for them’ and ‘he’ll grow out of it’. Unfortunately, he had. Betty knew the boy, a fragile, earnest teenager, rebellious as a convention of kirk elders. She had been amazed by the scene: all those people huddled together for support against four inches of hair on a harmless boy. It was as if, unable to feel for things that mattered, they all colluded in exaggerated reactions to trivia, indulged without risk in a ceremony of feeling.

Dan Scoular was her parents’ equivalent of long hair in their neighbour’s life, the proof that trouble does eventually come to every door. In that family summit meeting it became clear that it wasn’t who he was they had noticed but who he wasn’t. He didn’t have a very cultured accent. He wasn’t at university. He had no prospects of becoming a professional man. Everything they said to her when he was gone was another door closed on the possibility of their seeing him as he was. Their talk was the noise of preconceptions sliding home like bolts: ‘you’re young yet’, ‘more fish in the sea than ever came out of it’, ‘marriage is more than physical’, ‘not what we thought you would finish with’, ‘manners maketh the man’. This last came from her mother because Dan had not cut his piece of cake into segments with his knife but had lifted it whole and bitten into it.

‘Oh,’ her mother had said as if a small, domestic crisis had arisen. She put on one of her favourite expressions of rehearsed surprise. ‘I’m sorry. Didn’t I give you a knife?’

‘Aye, thanks,’ Dan had said. ‘But I never eat them.’

Betty had understood what had often troubled her about her parents’ politeness: it was a form of rudeness. Her mother in that moment had used what she liked to regard as manners to make somebody feel uncomfortable. For her mother and father the manners had become the most important things, because that way they never needed to go beyond them, could make their lives a continuous ritual round of attitudes in which any real feeling occurred like a short-circuit. The natural grace with which Dan had deflected an awkward moment into a joke was something they didn’t appreciate.

Her parents, she had decided, deserved their friends. From that night on, her sense of them had hardened. She realised how her mother’s pride in Betty’s achievements at school had never seriously related to what they meant about Betty herself. It was something her mother could brag about, something to wear like a fancy feather in her hat. She recalled something her mother had said several times when her parents were having what passed for an argument, a monotonous reshuffling of stock responses. ‘I did my duty by you, anyway.’ She meant she had given him a child. Her daughter was an expression of duty. Her father was always appropriately humble before the resurrected spectre of that often referred to and agonising experience, a nightmare of sickness and contractions and bravely borne self-sacrifice beyond his capacity to imagine. Betty herself had been accused of her mother’s pregnancy but had proved less susceptible to being intimidated by her birth than her father was.

Such memories were a farewell look at where she had been. From her reading she made up her own name for the place she was determined to leave: the lumpen-middle-class. If the dynamic of aristocratic life, she had thought, was the past (you inherited your status), that of middle-class life was the present, what you now materially possessed. For lineage, read money, the mechanical womb in which her parents had conceived her and from which they saw her own children coming. They seemed dead to the possibilities that lay beyond it.

That was one reason why, besides being in love with Dan Scoular, she had felt an intellectual identification with what she understood to be working-class life. The knowledge she had acquired of it through him made her want to be a part of it. From the first image she had had of him at a wedding to which she was taken by somebody else, she had wanted to know more about how he came to be the way he was, with a relaxed assurance and a smile that would have thawed a glacier. The company of his relatives she had found herself among welcomed her as if she belonged to a branch of their family they were delighted to make contact with again.

That same openness was something he had brought to their continuing relationship. She had never quite become immune to the attractiveness of his vulnerability. She had never known a man who was so obviously without effective defences. He didn’t hide behind any pretence of worldly wisdom. He seemed to have no sense of you that you were meant to be able to fit. He had met her with a kind of uninhibited innocence. It seemed to give them licence to find out together about themselves, and they did. Their previous involvements didn’t cause any aggressions between them. Marriage happened as a natural consequence, or so it had felt at the time.

But somehow the daily proximity of marriage had eventually compromised their original feeling. She began to see less attractive implications in his easiness of manner. She sensed him struggling to come to terms with how many restrictions there were on her apparent acceptance of him as he was. In their coming to understand the small print of each other’s nature, resentments grew.

The resentments were at first just the ghosts of things not done that haunt our lives in a gentle, house-trained way, the half-heard sough of chances missed, the memory of a relationship you allowed to starve to death through inattention, the place you might have been that stares reproachfully through the window of the place you are. But such resentments, born of the slow experience of how each choice must bury more potential than it fulfils, were always seeking incarnation. Then their tormentingness could be given shape, their slow corrosion be dynamic. In the shared closeness of a marriage, it was very easy to exorcise the growing awareness of the inevitable failures of the self to live near to its dreams into the nature of the other, to let the lost parts of yourself find malignant form in unearned antipathy to the other one’s behaviour.

It had happened to them, not dramatically but in small, daily ways. But then habit commits its enormities quite casually, like a guard in an extermination camp looking forward to his tea. Each day Betty sensed something in herself she didn’t like but couldn’t prevent from happening. She knew that what presented themselves to her as random thoughts were taking careful note, like shabby spies compiling a dossier against him.

One reiterated secret accusation concerned his propensity for violence. She knew it was grossly exaggerated in Thornbank. He had said to her once, Thank God, one fight avoids ten years of scuffles.’ He had confessed to her that he had never been in a fight without experiencing rejection symptoms of fear afterwards, a shivering withdrawal, a determination not to do the same again. She had seen that at first hand. Once he had struck her, one open-handed blow on the side of the head after – she admitted to herself afterwards – she had gone on at him for hours. His disgust at himself had been alarming, an almost tribal shame as of a native who has disturbed the graves of his ancestors. After her elaborate description of how far he fell short of being a man, she had stopped and begun to worry about his stillness. In the end, it had taken her two days to coax him like a small boy out of his self-contempt. He had promised her that it would never happen again, and it never had.

She believed she knew the truth of his reputation for violence. When he was young, it had been a gesture he knew how to make, which earned him an easy acceptance in the rough context he was born in, and it had remained something he could never believe in seriously. He had never hit the boys, even in a token way. Yet in the moments when her frustration with her own life left her with no charity for him, a voice in her that was like an echo of her mother would say he was a violent man.

The housing scheme they lived in, too, she would sometimes use against him. She liked their council house but she would keep handy in her mind her awareness of the haplessness of neighbours, the aimless family quarrels that they had two doors down, the way several people whom they knew organised their lives with all the precision of a road accident.

But all her accusations were subsumed under the one basic charge: he was wasting himself. He let days happen to him, that was all. Somehow, although less effectively and with increasing difficulty, he still provided a decent enough home, saw that she and the children lived more or less all right. But he seemed to make that his only purpose, had a life but no sense of a career.

She had loved that in him when he was younger. But she sensed, around her, friends she had known at school constructing weatherproof lives for themselves against all the inclemencies of middle age and she and Dan still lived as if they didn’t know the weather would change. He had no ambition. Under the constant abrasion of that thought, something she had always known about him, and had liked, turned septic and became a constant irritation. At school he had given up an academic course because it separated him from his friends. At one time she thought she had understood. He loved being out on the streets. He was big and strong and wanted to be in about life. There had been something in that she had admired. But it looked a lot less attractive to her now.

Part of the reason was a transferred guilt she felt about herself. When they got married, she had given up university. He had wanted her to go on but she had lost belief in what she was doing, felt she was dealing with hothouse concerns that would wither into irrelevance if you took them out into the open air. But though the action had been hers, it had turned with time into an accusation against him, as if she had given him herself and he had failed to justify the gift.

She knew the sense of betrayal was mutual. The openness between them had diminished and she sensed him believing the blame for that was originally hers. She knew he felt that no matter what he did now it would be misconstrued, that she attributed motives to his actions he had never imagined being there, so that he sometimes called her Mrs Freud. It must have felt to him that whatever small present he tried to give her, of a compliment or a generous remark, it was held cautiously to her ear and shaken, as if it might explode. He had once said to her in total frustration, Jesus Christ! Ah was tryin’ to be nice. If a fucking gorilla gave you a banana, ye would take it. It might be a gorilla. But it’s still a gift.’

These days she found herself wondering more and more what was wrong with the gift he had tried to give her. It wasn’t that he had welshed on the giving. Perhaps it was connected to the fact that he had from the beginning seemed to her potentially more than himself, to be in some way a future (not a past and not a present) that had somehow never been fulfilled. There was a dream in her he had never realised. The irony that hurt her was that the dream was perhaps inseparable from him. But perhaps it wasn’t. Lately, she had been thinking that maybe she had been too harsh to her own background. It wasn’t that she was in any danger of agreeing with her mother. But perhaps there was another form of that kind of life that she could live. The offer had been made to her.

Automatically, she lifted her coffee cup and found that the remains of her coffee were cold. The noises from the back green returned to her awareness. Putting down the magazine her mind had long ago abandoned, she crossed to the window and looked out. Seeing him preoccupied in playing with the boys, she found it easy to admit how much she still felt for him. She saw his attractiveness fresh and in the wake of the thought some of the good memories surfaced.

She remembered him coming in one night when he had been given a rise in wages. They were renting a small flat, waiting for their name to come to the top of the council housing list. She had felt cumbersomely pregnant with who was to be Raymond. Dan came in, glowing like a new minting, and smiled and shuffled his shoulders gallously in that way that could still make her feel susceptible. The memory of him then was something she wouldn’t lose.

‘What’s for the tea, Missus Wumman?’ he had said.

‘Fish.’

‘Wrong.’

‘How? It’s fish.’

‘No, it’s not.’

He danced briefly in front of her.

‘Ye know what it is? Ye want to know what it is? It’s Steak Rossini. Or Sole Gouj-thingummy-jig. That’s fish right enough, isn’t it? Or a lot of other French names that Ah can’t pronounce. It’s anythin’ ye fancy. Washed down with the wine of your choice. As long as it’s not Asti Spumante. Ye can put yer fish in the midden, Missus.’

‘What’re you talking about?’

Crossing towards the tiger lily she had bought, he proceeded to festoon it with notes.

‘We have here an interesting species. The flowering fiver plant. A variety of mint. Heh-heh.’ He turned to her and smiled. ‘Ah’ve got ma rise. We’re worth a fortune.’

‘That’ll be right, Dan. We need to save the extra. For furniture. When we get the house.’

‘That’ll be right, Betty. Trust me. Ah’ll sort that out when it comes. Tonight’s just us. We’re for a header into the bevvy, Missus. A wee bit of the knife and forkery in nice surroundings. Here, you been eatin’ too much again?’ He had one arm round her, stroking her stomach with the other. ‘You’ve got a belly like a drum. Ye want to see about that.’

The doctor says he knows what’s doing it.’

‘Right. Change into one of those tents you’ve got in the wardrobe. An’ I’ll hire a lorry to transport you to the restaurant of your dreams.’ He put his head against her stomach. ‘Okay in there? You fancy going out?’

He straightened up. She hadn’t moved. He turned her face towards his and kissed her. He smiled and shook his head at her, as if she would never learn.

‘Betty!’ he said. ‘Ye’ll have to stop worryin’ about money.’

‘Dan!’ she said. ‘You’ll need to start worrying about money.’

He winked at her.

‘After the night. Okay?’

But she was still waiting. Daft bugger, she thought, and smiled to herself. He was a man who made memorable shapes out of moments but neglected to work them into a coherent structure. Maybe he was trying to make a moment like that just now. She watched his intense participation with the boys, as if through the fond expression of that trivial game he could somehow convey his love for them, square accounts in some way with the unease that presumably dogged his relationship with them, as it dogged hers like a creditor. Maybe he was right, she thought. As she watched him charge up and down the green, she could believe he would soon be feeling a sort of nostalgia for this moment in its passing, that he was performing his own obscure ceremony of lastingness by implanting the same shared memory in each of them. They would all perhaps remember this laughter and this happy exertion in the pale sunlight. The three-fold wrestling match that followed looked to her like rough, amateur faith-healing, Dan’s attempt to cure small alienations by the laying on of hands. He looked up suddenly and noticed her and waved. She waved back.

But by the time he came in with the boys, they might as well have been waving goodbye. As the late afternoon decomposed into evening around them, they remained as distant from each other as they had been earlier in the day, again only meeting obliquely through the children (Betty re-establishing clear contact with Raymond over the meal) until Dan eventually stood up and stretched and, as his body relaxed, her body tightened, as if they functioned by mutual contradiction. As he went across to take his jerkin from the back of a chair, she felt beginning one of those exchanges of small utterances that mean so much, phrases packed with years, expressions of the microchip technology of married speech.

‘Ah, well,’ he said.

Her understanding of what he had said was roughly that she knew where he was going, he knew that she knew where he was going since it was where he usually went at this time, that he would prefer not to have any expressions of amazed surprise and he would like to get out the door just once without complications.

‘Your homework checked, Raymond?’ she said.

She was reminding him that they were supposed to be a family, that there were other responsibilities in life besides following your own pleasures to the exclusion of everybody else and that she didn’t see why everything should be left to her.

‘Aye, love. We’ve checked it,’ he said, conveying that he was refusing to get riled and she was wrong to think he would neglect his duties as a father. Putting on his jerkin was a reminder that he was going out anyway, no matter what she said, and wouldn’t it be better to let it happen pleasantly.

‘Where are you going?’

It wasn’t a question, since they both knew the answer. It was an invitation to feel guilt.

‘Ah thought Ah’d nip out and have a look at Indo-China.’

‘You going to the pub?’

He nodded.

‘You can’t think of anything else to do?’

‘Well, you couldn’t last night. Ah don’t remember you gritting yer teeth with those vodkas.’

‘But last night wasn’t enough for you?’

‘Look, Betty. It’s Sunday night.’

‘It’s Sunday night for everybody else as well.’

They went on like that for a short time, exchanging ritual and opaque unpleasantries, not connecting with each other so much as remeasuring the distance between them. She knew she would remember and examine things he had said, open up a small remark like a portmanteau and find it full of old significances that had curdled in her. As he went out, she didn’t know how much longer she could bear to watch him let circumstances take charge of him, erode him. She knew from a thousand conversations the reality of his intelligence but she despaired that he would ever apply it constructively to the terms of his own life. How often they had tried to talk towards an understanding of what was happening to them and it had been like trying to talk a tapeworm out through your mouth, never to find the head. He seemed to her to live his life so carelessly that everywhere he walked he was walking into an ambush. She was tired of shouting warnings.

The sky looked different here to Eddie Foley. There was so much of it. Getting out of the car, he felt nearer to the presence of the wind than he did in the city. It seemed to touch him more directly, make him more aware of it. He stood in the car park and stared at the bulk of the Red Lion. It was a strange building with an odd, turreted part at the back of it. There was a big, dark outhouse, the purpose of which he wondered about.

He breathed in deeply and, finding himself put down here outside his routine, remembered being younger. There had been a time in his early twenties when he and a group of friends used to look for out-of-the-way places like this. One of them could get the use of a car. They had all finally admitted to one another how amazing women were and it felt like a shared secret. Weekends were for them what an unexplored coast might have been to a Viking. They piled into the car and went ‘Somewhere’ and talked among themselves and talked to girls and drank and the password of their group was ‘we’ll see what happens’. He wished he were coming here now on those terms. He wanted just to go into the place and have a drink and see what happened. He wished they hadn’t a purpose in coming. But Matt Mason didn’t seem to have noticed the place as itself, looking up at the lighted window that faced out into the car park.

‘Move the car up to opposite the window.’

Eddie climbed back into the car, drove it towards the lighted window and then backed against the opposite wall of the car park so that the Mercedes faced towards the window. He shut off the engine and doused the lights. Lighting a cigarette, he studied the other two through the windscreen.

He saw Billy Fleming watch Matt Mason attentively, like a trained retriever waiting for the signal. Seeing Billy’s preoccupation silenced by the windscreen and framed in it, as if through the lens of a microscope, Eddie thought what a strange thing he was – an expert in impersonal violence. He felt no compunction about contemplating Billy so coldly. Billy wasn’t his friend. He wasn’t anybody’s friend, as far as Eddie knew. If Matt Mason had given Billy his instructions and nodded him towards the car, he would have come for Eddie as readily as anyone else. It was how he made his living, being an extension of Matt Mason’s will.

He did it well. Eddie had several times been astonished by the agility of that hugeness. But the results of that dexterity had made Eddie look away. He remembered one man whose face looked as if it had been hit by a small truck. Could you talk about doing anything well the purpose of which was so bad?

Eddie would have felt contempt for him except that he was honest enough to admit to himself that he couldn’t afford it. His own position wasn’t so much different. He might spare a thought for the man who imagined he was just coming out for a quiet pint, but that was as useful as flowers on the grave.

Eddie might like to believe that he still had a conscience but the main effect of it at the moment was to make him glad he couldn’t hear what was being said. It meant he didn’t have to worry about it too much. He just sat, smoking his cigarette and knowing his place. He watched Matt Mason prepare what was going to happen. He looked like somebody setting a trap for a species he understands precisely.