Читать книгу Farber Plays One - Yaël Farber - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

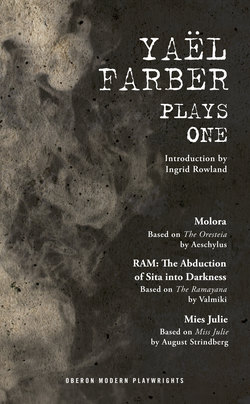

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Yaël Farber has described her involvement with theatre as a mission. At the heart of her productions, therefore, no matter how dark, there is always a luminous vision to guide characters, actors, and audience forward from the magical rite of performance into a transformed awareness of normal life. Paradoxically, as in these three plays, she draws power from traditional stories and traditional rituals to address contemporary problems head on. Unlike the ancient Greeks, who hid away the most graphic events of tragedy – murder, suicide, rape – Farber shows it all. As a director, she drives the human body to extremes, asking incredible agility of her dancing, leaping, whirling, wrestling actors, pressing their willingness to bare body and soul to the very limits of endurance. She makes comparable demands of her public: we are present to bear witness, to be engaged rather than simply entertained. Each of these plays begins with a warning that production on a proscenium stage will ruin its effect; players and public must meet face to face, on the same level, to recognize their common humanity – and, sadly, inhumanity.

Furthermore, each of these three dramas is based on a classic of dramatic or epic literature transported to a new place and time. Molora (2008) sets the ancient Greek saga of the Oresteia in contemporary South Africa, with the Commission on Truth and Reconciliation taking the role of the ancient Athenian Court of the Areopagus. Ram: the Abduction of Sita into Darkness (2011) recounts a grim episode from the Hindu epic Ramayana in connection with a strike by modern Indian sanitation workers. Mies Julie (2012) moves August Strindberg’s Fröken Julie from the midnight sun of a Swedish Midsummer to Freedom Day on an arid South African farmstead. And with each of these transpositions, something remarkable takes place. Rooting these plays in such specific times and such specific settings actually enhances Farber’s power, as playwright and director, to draw out their universal qualities. For these great tales, times and continents hardly matter; our similarities as human beings prove stronger than our differences, especially when we gather in a circle to hear a story unfold.

At its origin, the Oresteia was a tale of the dying Mediterranean Bronze Age. Agamemnon, the general who led a thousand Greek ships to conquer distant Troy, belonged to the last generation to rule from a series of massive palaces decorated with elaborate frescoes and brimming with gold. Shortly after the Trojan War, between about 1200 and 1100 B.C.E., this palace civilization was destroyed; political systems broke down, writing was lost, Greeks descended into extreme poverty. Memories of that breakdown persist in the story of Agamemnon’s homecoming from Troy: his queen, Clytemnestra, has taken a lover during his ten-year absence, and when he finally returns, she kills her husband and abandons their children. Electra, the daughter, descends into bitterness. Their son, Orestes, is bound by tradition to avenge his father’s death by slaying the murderer, but that murderer is his own mother. His conflicting obligations potentially make Orestes a monster no matter what he does; significantly, his name means ‘mountain man’ – he is, by fate and by definition, a kind of savage. All three of the great Greek tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, wrestled with Orestes’ dilemma, using it as a way to call for new, more profound forms of justice, aware that their ancestors had created a new civilization, their own, from the ruins of the Bronze Age. In their retellings, Orestes slays his mother, but is tormented by the Furies, his mother’s avenging spirits. In his great tragic trilogy. Aeschylus finally turns Orestes over to a court of law, which reaches a split decision. In a spectacular finish, Athena decides to acquit him, but she also gives the Furies a new home and a new cult in Athens.

In Molora, the dying Bronze Age becomes the dying system of South African apartheid. Farber replaces the ancient Greek chorus with a chorus of Xhosa women singers. Those ancient Athenians sang melodies and danced, vigorously, in patterns we can only guess at now. But the hypnotic two-tone throat singing of this contemporary chorus creates an ecstatic atmosphere sufficient in itself, one in perfect harmony with the play and with its new South African venue. Aeschylus ended his famous Orestes trilogy of 458 B.C. with a torchlight procession as dusk fell over Athens, knitting up all the unanswered questions of his story with the irrational, energetic rush of pure celebration. The final chorus of Molora may be sung in a different language to different instruments than those known to Aeschylus, but the language of bodies in motion knows no borders, and the effect of this South African dance must be no less exhilarating than the memory of that long-ago torchlight parade. Likewise, the sword dance that Orestes performs in Molora as he circles around a smoldering altar hews with absolute truth to the spirit of Greek tragedy, not only because tragedy is the stylized product of an ancient circle dance around a burnt sacrifice, but because, in human terms, Orestes needs to work himself into a frenzy before he can contemplate doing what he must do with that sword – namely drive it into his mother. But Farber’s most brilliant transformation of the Orestes legend is to have the chorus, as the embodiment of Truth and Reconciliation, stop the murder before it has happened, to hold Orestes to their superior, forgiving justice before he awakens the Furies.

The justice in Ram, by contrast, is a bitter justice. The original version of the Hindu epic is thought to date from about the same time as Athenian tragedy, the 5-4th century B.C.E., its 50,000 verses centering on the battles of the virtuous hero Rama against vice in all its various forms. Farber, however, concentrates her attention on the story of Rama’s wife Sita, who represents purity and female divinity as Rama himself represents male virtue, and joins him in his battles. When Rama and Sita are living in the forest as exiles from his rightful kingdom, Sita is abducted by Ravana, the monstrous king of Sri Lanka. With the help of his brother and the Monkey God Hanuman, Rama eventually rescues his wife, but he doubts that she can have maintained her purity during her captivity; she finally proves herself by passing through fire. Even after they have been reunited, rumors persist about her, and eventually Rama abandons her (although they reunite again at the end of the Ramayana). A televised version of the story was extraordinarily popular in India in 1987-88, so much so that it sparked a strike by sanitation workers across northern India in 1988, who demanded that the federal government commission more episodes of the program. In Farber’s retelling, the theatre itself becomes a village gathered around a television set like the Indian audiences in 1987-88, and the discussion of Sita’s purity becomes graphically urgent when Ravana not only imprisons Sita, but finally rapes and kills her. Her ravaged physical self appears as a separate ‘Sita-body’ that takes its own part in the drama; Sita herself, like Rama, is immortal, the human embodiment of a goddess, but this process of psychological removal is well known in real victims of sexual assault. If the Sita-body is violated, then, does this mean that Sita herself is also defiled? Furthermore, as Ravana will discover, his act of violence ultimately turns back on itself without Rama and his armies having to come to the rescue. This retelling of the Ramayana holds Rama to a more trenchant definition of virtue than the traditional warrior’s prowess, and the loss of Sita is portrayed as an absolute loss to any society that suppresses the feminine side of divinity.

Mies Julie presents an equally harrowing examination of the dynamics between men and women, further complicated by conflicts of race, class, and rootedness in a particular place. Strindberg, in 1888, portrayed a consciously Darwinian struggle between Miss Julie, the countess who represents Sweden’s fading aristocracy, and the upward strivings of the valet Jean, in contrast with the long-suffering, pious cook Christine, Jean’s fiancée. It is Jean, in the end, who hands Miss Julie the razor with which she will presumably commit suicide offstage, thus ensuring the survival of the fittest. Farber shifts this drama to a South African farm in 2012, where Julie is no longer aristocratic, but simply white; in her own way, then, she is as tough as John, the black servant she has known since childhood and begins to challenge on a hot April 27, when the country stops to celebrate Freedom Day. Soon, of course, we see that true freedom from apartheid is still no more than a distant hope; Julie, John, and his mother Christine are entirely in its thrall. In Strindberg’s staging, Jean and Julie withdraw to Jean’s room when their flirtation takes a serious turn; here John and Julie copulate, hard, on the kitchen table in front of us. Like Strindberg’s couple, Farber’s pair dream in their uncomfortable afterglow of starting a hotel together, and in today’s world the idea has a plausibility it may not have had in Sweden in 1888. It is all the more shocking, therefore, when John kills Julie’s pet bird as useless extra baggage; apartheid has brutalized him as much as it has brutalized Julie at her most imperious. For her part, Christine, obsessed with the presence of her ancestors buried beneath the foundations of the house, brings on a searching discussion of who truly belongs to the soil of South Africa; for Julie’s ancestors lie buried there as well. Ultimately, it is this very sense of rootedness that destroys the brief dream that John and Julie spin of running off together, and when Julie kills herself – as she does, again, before our eyes – it is with a farm implement, a sickle, driven into her womb, which came so close to fostering the mixed-race children of a new South Africa. It is impossible to come away from Ram or Mies Julie without feeling that the world must change; Molora points the way. Yaël Farber’s theatre will leave no participant unmoved.