Читать книгу Across the Three Pagodas Pass - Yoshihiko Futamatsu - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

It is a long time, forty years, since the end of the Second World War, and with the lapse of time what happened in it is like a distant historical fragment of a past which people have now forgotten. With the end of the war we Japanese set up a new constitution which outlawed war, sought peace and declared that Japan would never again go to war.

But how can the present generation who have no war experience understand what war is? By the same token, how can they bear malice, how criticize, how amend the real truth? To them it is the responsibility of those who did experience it to tell them the reality … they can describe it and it is plainly their responsibility to do so. One must admit, however that they are getting few in number.

When our army made their strategic attack on India, they planned a railway for military purposes to transport supplies overland. After the war, the construction of this railway was the background to the film Bridge built in the Battlefield (Japanese title of Bridge on the River Kwai), and the prisoners in it were supposed to be those who sang the theme song the ‘River Kwai March’. Moreover, because so many were sacrificed, the slur, ‘Death Railway’ was slammed on it. Full details of the actual conditions of its construction do not now exist. The film is full of errors, and to have dubbed it ‘Death Railway’ is clearly far from the reality.92

Its construction involved an unusually difficult operational sequence in military action in a war area. To use prisoners-of-war and their help to complete the task constituted a unique phenomenon in a world railway construction.

In mountainous terrain in a jungle belt pivoting on the Three Pagodas Pass on the Thai-Burma frontier, construction meant enduring a climate of sweltering heat and heavy rainfall, meant battling with epidemics of serious diseases such as malaria and cholera, and mastering nature in the form of jungle for a distance of 415 kilometres and in the space of one and a half years completing the task: the solid fact, in my opinion, is that the Japanese left behind them a record of considerable enterprise.

I myself was a railway engineer in one of the railway construction units and I know the true facts about the construction of the railway. I can describe their significance; it is meaningless, I think, to go on dwelling on the deaths and destructions one-sidedly.

In April 1981 Mr Geoffrey Adams, an Englishman who had worked on the railway as a prisoner-of-war, visited Japan and came to see me. He left with me a copy of his record of experiences of the war years entitled, No Time for Geishas.93 These recollections were those of a British prisoner-of-war of the actual conditions, but they were an impartial, coolly-written account. Then again, later on in 1983 Mr James Bradley, a former prisoner-of-war who made an escape, wrote about his experiences, and sent me a copy of his book, Towards the Setting Sun.94

Mr Adams makes the following statement in his memoirs:

We British hate war, but you can’t deny it exists. It benefits no-one and we must hold ourselves aloof from it. To leave behind a record of my experiences of what it was like in those days is, I think, something that will acquaint the coming generation about what war really is. I do not forget the suffering my experience of war entailed, but we must forgive the men who caused it …

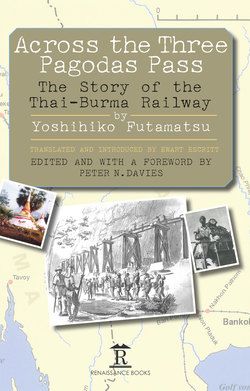

I can agree with Mr Adams’ opinion and so, taking advantage of their permission, I can quote from time to time from both these gentleman’s memoirs and from my own experience, give my book the title of Across the Three Pagodas Pass, and record one aspect of the history of the construction of the Thai-Burma Railway. This record transmits historical truth. For those who seek peace, if I hold firm in telling them something about the struggle, I shall win an unanticipated pleasure.

Futamatsu Yoshihiko

July 1985