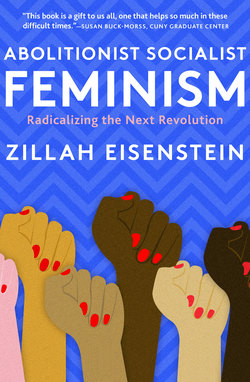

Читать книгу Abolitionist Socialist Feminism - Zillah Eisenstein - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеII. A BEGINNING OF SORTS

What I write here owes itself to more than forty years of dialogue and activism with feminists of every color. These dialogues were embedded in conversations about hundreds of books and articles read and shared, and thousands of actions taken. So this is a collective project for me. As I write, I see and hear the many sister (not cis-ter) friends and colleagues and comrades who have been a part of this conversation.

I am humbled and searching and determined as I continue to write in such troubled times. People are living through political and environmental cyclones. My thoughts are about the feminisms that have improved the way humanity can see this world, live in this world, and change this world.

I try to displace the idea that women as a sex class need a “oneness,” a central definition. Today, unlike earlier radical feminism, sex class is to be understood only in terms of its overlapping multiple partialities. So yes, sex class, and raced power, and economic class are each varied and heterogeneous, and this gives them their shared political import.

Complex power systems constitute the overlapping commonness that disallows any oneness, homogeneity, or unity. Instead, ideas of “heterogeneous commonality” and “common differences” that are “differently similar” make up the sexual class of women. I am looking in/at this moment to find new articulations of these complex, overlapping relations of race, sex, class, and genders—between and inside of each. Disabilities and trans identities further illuminate this process.

Why are women’s lives more differentiated today within the structural systems of patriarchy than in earlier historical periods? Most women across racial lines are working overtime doing the labor necessitated by misogyny and they also occupy sites that were once closed to them within this very system of male privilege. But this latter change of females to new sites in the public sphere—presidents, CEOs—has little to do with rearranging structural or collective power.

Women have been or are presidents and secretaries of state and foreign ministers in the United States, Haiti, Liberia, Argentina, Chile, Jamaica, Germany, France, India, Pakistan, and many other countries. Meanwhile, five hundred thousand women die annually in child-birth. And too many millions are displaced, traversing the globe as refugees.

Everything changes and nothing changes. Both of these statements are valid, and with the uncertainty comes new possibility. I am looking for the new-old meanings that express both change and stasis. Feminisms are both stuck and have moved beyond languages that are both necessary and outmoded. Should we still use the term patriarchy when so much has changed? Why is masculine privilege today more diversely written on women’s bodies of all colors and many classes? How can Google still think it is OK to pay women less than men in such obvious discriminatory structural fashion?

Distinctions like first and third world still apply, and they also do not. The third world lives in New York City, and Kentucky Fried Chicken operates in Kenya. The second world disappeared along with the Soviet Union in the revolutions of 1989. Indigenous feminisms are constructed within settler and imperial locations and stand against western imperial feminisms of all sorts.

Female bodies, whatever cultural and racial and class form they take, are a location of both power and powerlessness. If women are bound and gagged, it is because they have potential power. Women will be beaten or raped or mutilated because of this potential power. If one could, one would just ask any enslaved Black female about her body and her punishment, about her power and her powerlessness as a piece of property.

If women’s bodies were not sites of power, they would not be the battleground that they are. Sometimes this struggle to control is individual and personal through a sexual violation that is silenced and shamed. And sometimes the struggle is more public, as in the fight over the legal status of abortion, since abortion is a proxy for controlling women’s bodies.

The struggle over the legal standing of abortion stymied the unification negotiations between East and West Germany in 1990. West Germany was initially unwilling to accept the more radical abortion laws of the East. Abortion in the United States remained unresolved in the battles over the Obama health care reform. Reproductive rights and self-determination of one’s female body are central to all the newest reformations of misogyny—in the United States, in Poland, and in South America, for example. They remain central to the struggle for control of the US Supreme Court.

So female bodies share a homogenous standing in misogyny, while they are also varied in relation to systems of power. On the one hand, there are Hillary Clinton, former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, former president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, Prime Minister Theresa May of the UK, Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, female defense ministers in Spain and France, and female soldiers at Abu Ghraib.

On the other hand, there are poor migrant women laborers, female flower growers in Honduras, mutilated girls and women in Rwanda, indigenous women protecting land rights throughout the globe, Black women and their children suffering the greatest effects of Hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, and Irma, detained women immigrants in the United States, raped Rohingya women in Myanmar, women of #MeToo.

This disjuncture of power among women is why US antiracist socialist feminists took part in the International Women’s Strike of 2017, calling for a feminism of the 99 percent. It was time to come together with restaurant workers, Wal-Mart employees, domestic workers, immigrant women, Black women, and many others. Some of us wear veils, others reveal their faces; some are tattooed, others not; some are trans, some are indigenous, some are gay, others are disabled. Some are made of many of these multiple parts.

As I rethink and update all the changes that are within my purview, I offer an abolitionist socialist feminism as a possible organizing site for the audaciousness already at hand. I am uneasy and doubtful but also equally passionate that radically progressive people —the big “we”—can transform the world, especially with girls and women of color offering leadership around the globe. And because a revolutionary imagination is the most meaningful thing “we” have to offer, let us all try to find it.