Читать книгу My Sack Full of Memories - Zwi Lewin - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

My name is Zwi – that’s the name my wife, children, grandchildren and friends have always called me – but a name I only acquired as a teenager when I first arrived in Australia. Like the Queen dubs a Knight with a new name, my Jewish youth group, Bnei Akiva, dubbed me Zwi those many years ago, but I wasn’t short of names, as by then I already had four names and Zwi was the fifth, the final and the most satisfying one. So, please call me Zwi (pronounced as Tsvee).

I live in Melbourne, Australia, in my ninth decade of life. I am that old man who saves himself from the long walk to synagogue by using a motorised scooter, yes, permitted even on Shabbat (the Sabbath); the one who is getting slower going up the stairs, carrying aches and pains and puffing a little at times; the person you might not glance at as you pass. Even I don’t recognise myself, for in my mind only a little time has passed since I could have outsprinted you on my daily run to the beach, sent a sizzling backhand down the line or taken a ruckman’s mark over a pack. Like you, I was young and indestructible.

I have enjoyed living in Melbourne, for this city, which I have made my home for most of my life, has allowed me to breathe the air of freedom, to make my way among the least judgemental and friendliest people on earth, to create a home and family, to practise my beliefs; and yet I note that Melbourne has recently been displaced as the world’s most liveable city by Vienna, Austria – a decision demonstrating once more how quickly the cracks of history are smoothed by time, and how the world forgives and forgets. Austria is the country that spawned Hitler and rapturously cheered the arrival of the Nazis; and Vienna, a city glittering with broken glass on Kristallnacht, a city whose art galleries fought to keep stolen artworks as their own, a city whose Jews were expelled or dragged to extermination camps, is now considered the best place to live on this planet.

So, as Zwi, I have lived for so many years, but this was not the name written on my original birth certificate. I suspect it was in a drawer in our family home in Bielsk Podlaski, Poland, and was lost, but trivial compared to what else I lost when the Germans invaded.

On that certificate you would find my parents had named me Herszel, a Yiddish word meaning ‘deer’. Yiddish was my first language, for it was the common language of the Jews of Europe whose borders did not constrain our tongue. A language now taught as an oddity, for Modern Hebrew is the language of Israel and the basis of Jewish education worldwide. The dying of Yiddish is but collateral damage of the extermination of six million people, but with it went a mountain of culture and literature.

It was not long after I arrived in Melbourne that I was swept up in those forces pushing for Hebrew as against Yiddish and, as I have said, Yiddish lost.

Bnei Akiva, the religious youth movement I first joined, responded to this new boy called Herszel, so recently arrived from Europe with the ever-so-Yiddish name, in the way you would expect. It was, after all, the early 1950s and the Jewish world was changing. Israel had been established in 1948 and Bnei Akiva was naturally also strongly Zionist. It hoped that us teenage members would ‘make aliyah’ and ultimately live in Israel. Bnei Akiva decided I needed a Hebrew name and so I was dubbed Zwi, which is the Hebrew translation of the word ‘deer’.

I arrived in Melbourne by ship, as immigrants did in those post-war years, on 10 November 1948. The events of a week earlier, the first Tuesday in November, would have still been reverberating around the city. Rimfire had won the Melbourne Cup, ridden by an apprentice, a boy just a day short of his sixteenth birthday. It was a good time to be a teenage boy arriving in the city.

The shipping records illustrate the attempt of the Australian officials to spell ‘Herszel’, for on arrival I was Herzel Lewin, not bad and only missing one consonant. A cousin, waiting at the dock to meet her European refugee family, a schoolgirl, turned her nose up at my foreign-sounding name, for Herszel was certainly not anglicised enough for her liking, so she suggested an alternative.

Not speaking any English, I accepted her decision and so, based on the fact she was studying Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest at school, I became known to the Australians as Ernest. I was Ernest in earnest – Ernest Lewin when enrolled in my first classes at state school, but as Aussies love to shorten a name, I was soon called Ernie.

So, I have always had the three names in Australia, my Jewish friends and family calling me Zwi, while at school, work and in business I was Ernie. Only my mother and sister kept to my birth name and in their homes I was always Herszel.

Others imposed the other two names I have responded to. Grigory by the Russians and Gjegus by the Poles, names I have not been called by for over seventy years. When I became a grandparent for the first time, I decided that rather than getting called Zaida or Pa or the like and add yet another name, I would stick with Zwi.

If I had my birth certificate from my home in Bielsk Podlaski the records would show my father’s family name in Poland was also spelt Lewin. The ‘w’ in Polish is pronounced ‘v’ and my first cousins in the USA use Levin as their surname.

The name Lewin derives from Levi, the tribe of Israel with the honour of being the servants to the high priests, the Kohanim. At the high holy days, we Levyim are still required to wash the hands of the Kohanim before their blessing of the congregation. This would have been a long Lewin family tradition, for my family in pre-war Poland were devoutly religious as well as being wealthy merchants.

Unlike my first name, my Lewin surname has never changed.

In my ninth decade – yes, I am over eighty, but by how much is a question that my putting a finger to the keyboard has disturbingly raised. Age, my age, signified by another candle to blow out on a cake each year, was known to me, until now.

Children today are so aware of their birthdays. As a young child living in such strange and tumultuous times, I was not aware of having any birthday celebrations. I have always believed I was born on 13 February 1936, for that is the date on my Australian documentation, my passport and my driver licence, all created long after my birth. Not long ago I celebrated my eightieth birthday with family and friends but in researching this book I have found I might have been a couple of years late.

The entry card to Tashkent in Uzbekistan in 1941, which still exists, has my date of birth recorded as being 1934, not 1936. This can easily be dismissed as an error in transcription, accidental or deliberate. More compelling is the only photo of myself with my parents, dated in pencil on the back as having been taken in June 1935, showing me as a child well over a year old, for I am standing, supported by my father. Why have I never examined the back of this photo before? Have I gained or lost a few years of life?

My being two years older than I thought does explain why so many of my early childhood memories are so vivid. In preparing this book, I now assume I was born in 1934. Be patient with me, dear reader, for I will time-slip later in the book as if it was science fiction rather than fact and become younger once more when I arrive in Australia. For what I have always believed is embedded deeper than what I now know.

The missing birth certificate would have shown I was the result of a mixed marriage. My father, Yitzchak, was Polish and my mother, Gitel, was Lithuanian. Both, however, were Orthodox Jews, and the national differences were probably the result of the constant flux of borders and rulers in that part of Europe, because both countries at the time of their birth had long been under Russian rule.

The same missing certificate would most likely have identified my place of birth as the Polish town of Bielsk Podlaski, my father’s town, not far from the Lithuanian border. This town was only 40 kilometres from Bialystok, a much larger city with a revered Jewish community. Bielsk Podlaski was considered part of the Bialystok environs and both of them had Jewish maternity hospitals. While most births may have been home births at the time, my parents, being well-off, may have opted for one of the hospitals.

In 1956, when I was drafted into the Australian Army for National Service, I received two call-up notices in the mail, one for Herszel Lewin and a second one for Ernest Lewin. It was Ernie Lewin who arrived in Puckapunyal to serve his new country.

There is a quote from The Importance of Being Earnest that concludes that ‘memory is the diary that we all carry about with us’.

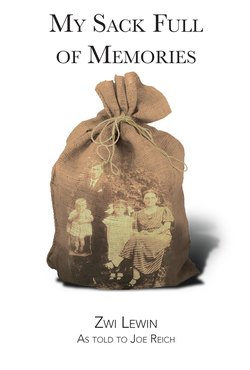

I wish it were so easy to keep such a diary in my mind. For to me, memory is like a sack on my back and each memory is an individual stone I carry in that sack. For a young child – and so much of what I want to tell you occurred when I was very young – perhaps the sack was too small, because the stones fell out and I now remember so little. Other heavier stones were added, stones that were painful with their jagged edges, stones that made me cry and stones that left little room in my sack for happy memories. Many of these stones are also missing, but they have left a sadness that has lingered.

To help me create this memoir, I am grateful for having cousins to help fill the gaps. My late mother’s younger sister, Bruria Pekelman, who has also passed on, created a family tree of my mother’s family with her daughter Mina and her son-in-law Harold.

Travelling into the past, like travelling at any time, requires a map. My map was this family tree and the starting point when placing my mother into her family. My father has no family tree; apart from the ghostly photographic presence of a few of his siblings and parents, nothing remains.

This concept of a family tree is something I hadn’t encountered until more recent years when the Jewish schools, in their wisdom, realised that with the passing of more than just time, the history of our community might well be lost. Each child was given a Roots project. I was soon being asked questions about my parents, their parents and so on. For Australian Jews, or those the Holocaust bypassed, a family tree might have many branches and deep roots, at times back to the seventeenth century, as evidenced by the hundreds attending publicised family reunions. The tree of my memory has few branches and is not very tall.

Aunt Bruria may well have been younger than I am when she created our family tree, the starting point for my time travels. There are questions about some dates she has allocated as the bookends for my forebears but then I sympathise, for I also have difficulty putting dates to people or events in my life. We are of the generation without the constant recording or sharing of events. Yes, there was a time before Facebook.

My aunt Bruria’s daughter Mina and husband Harold, together with their daughter Sharon, travelled a few years ago to Vishey in Lithuania, the town of our mutual grandparents – a town time has forgotten, but will never forgive. From them I learnt of some firsthand accounts of the destruction of a Jewish presence in what was once a vibrant Jewish community.

My other cousin, Azriel, lives in Israel and, being some four years older than me, is a more reliable witness to shared early childhood events. He has provided much valuable detail. Even so, it seems at times there were a few versions of the same stories. They differ in trivia more than substance. I will try, however (as those of you who know me would be aware), to stick to the facts and perhaps conjecture only when there are documentary or memory conflicts or a need to explain.

Why am I writing my memoirs, you might ask. Well, as I look with delight at my growing family, I realise how different my life has been and especially my childhood when compared to theirs. I look lovingly at my children and now their children, my grandchildren, as they attend kindergarten, school and university supported by caring parents and grandparents who feel joy as they learn in relative safety.

My life has been so different that it might appear to be the wildest fiction. Imagine, a young boy taken from his home, never to see his father again, transported half a world away to an orphanage on the road between China and Europe. A place where they didn’t speak his language, where he had virtually no schooling and his greatest memory is of constant hunger.

Imagine … that boy was me.