Читать книгу My Sack Full of Memories - Zwi Lewin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

At eighteen, my mother was brimming with life, for she was always active and willing to stand up for herself, but there were certain tasks that were not the responsibility of a young woman. The small Jewish community had its shadchen (matchmaker), whose role it was to find a suitable husband for such a girl.

My mother would have been something of a catch, the granddaughter of Rabbi Meir Kannengiser, her mother’s father who had passed away some years earlier, but whose status would have counted and, of course, the long-lost judge. Yichus is the Yiddish word for the status a good family brought you.

The process of choosing a suitable husband for a girl was left to her parents and the shadchen, who would between them balance status, knowledge of the Torah, and the ability to afford to care for their daughter and provide for a future family when assessing the prospect. Decisions not made easily, but it was the way they, their parents and grandparents had met and married.

To marry for love was considered foolish, for such feelings might overcome practicality and be unlikely to be accompanied by a dowry. Love wasn’t a concept much considered, as Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof bemoans, waiting twenty-five years after their marriage before asking his wife if she loves him.

And so it was that my mother, Gitel, was to get married. First, a marriage agreement ceremony known as a t’noyim would take place. It was at this function that she was to meet her future husband for the first time. A t’noyim was much more than an engagement party, instead being an important moment of commitment accompanied by a signing of a document. This confirmed the terms of the marriage, including the wedding date and any dowry. The finality of this commitment was emphasised by the famed Rabbi of Lithuania, the Vilna Gaon, in the eighteenth century, a time when a more conservative rebellion was occurring against the Chassidic movement which it was felt was devaluing learning by being open to all. The Vilna Gaon advised that the breaking of a t’noyim commitment was a greater sin than divorce.

The mothers of the bride and groom symbolically broke a ceramic plate, often hand-painted for the occasion, together, as if to emphasise, as Shakespeare would say, ‘what is done cannot be undone’.

Let us imagine the t’noyim. It was an afternoon tea at the Lazovski home when my mother was to be introduced to her future groom for the first time. The two families would have been there, but whether Chaim and Mina had a larger party with other guests I cannot be sure of, for they were not into overt celebrations. What I do know is that when my mother peeked through the curtains into the room and saw her husband-to-be, all she later said was … ‘I immediately knew he wasn’t for me.’

I suspect she thought he was too old.

Once the plate was broken, there was no backing out. A bride who didn’t go ahead with the wedding from then on would be scorned, shunned by her family, and unlikely to ever marry. This my mother knew as she let the curtain fall and crept away.

The afternoon was getting late. Most likely the groom was asking his parents what was happening, for he too was keen to see the bride his parents had chosen for him. Rivka, the next oldest girl, may have been asked to go to get Gitel, whose attack of nerves was out of character for such a level-headed girl, or else my grandmother Mina may have excused herself from her guests and gone to fetch her.

An open back door allowed my mother to flee across the unmade road, unseen by anyone, up the gentle slope to the woods at the back of town, and from there she vanished. It is said she walked through the woods, swam across a river at the porous Lithuanian border and made it into Poland some twenty or so kilometres away.

This, by a woman I never knew could swim.

Perhaps, looking back on the family dynamic I have outlined, there is a simpler explanation. Her mother, Mina, may have supported her in the decision to leave, for it was likely that the highly opinionated Chaim alone had chosen the groom. Mina was a more progressive woman, as shown by her actions, when she later encouraged her youngest daughter, Bruria, to leave Vishey and study nursing in Germany. My grandmother, Mina, may have shared my mother’s dismay at the choice of groom. So it may not have been the sudden fleeing of a young girl, as I have been told, but perhaps planned ahead, for Bruria remembered Gitel coming to her just before she left with a gift she had knitted for her. Not only was such a gift unusual, for Bruria had never received such a gift before, but my mother also told her it was a secret.

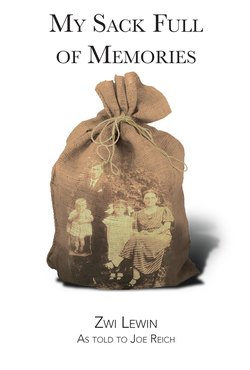

The only photograph of my grandmother Mina, taken after my mother had left. With her daughters Rivka and Malka beside her and Bruria holding the ball in front.

Days after this giving of the gift my mother was gone, and as a result Bruria didn’t see her favourite older sister again for another thirty-five years.