Читать книгу Impostures - al-Ḥarīrī - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

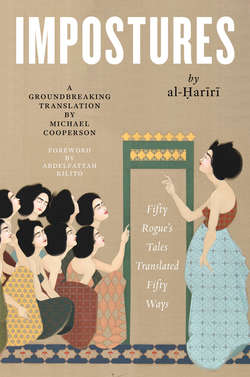

A Basran Boswell

ОглавлениеIn some ways the English literary pair that most resembles al-Ḥārith and Abū Zayd is James Boswell (d. 1795) and Samuel Johnson (d. 1784). In both cases we have a narrator eager to learn from, and to impress, an older contemporary famous for his command of language. The senior member of the pair does not disappoint when it comes to eloquence, though in both cases he occasionally exploits his admirer or treats him with contempt. This Imposture, which is Englished after Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, involves a game similar to one played in Johnson’s literary circle: taking an existing poem and improving on it, usually on the spot. In the original, the first couplet cited is by the Abbasid court poet al-Buḥturī (d. 284/897), and the verses intended to top it are put into the mouth of Abū Zayd. In English, the first couplet is by Edmund Spenser (d. 1599) and the toppers by Philip Sidney (d. 1586). The common element is the comparison of teeth and tears to pearls. As Abū Zayd continues to improve on the verses, the similes become more and more elaborate. In English, the series culminates in Sidney’s Sonnet LXXXVII, which, like Abū Zayd’s poem, describes a lovers’ parting. The English also includes a few phrases from Chappelow’s 1767 translation of this Imposture.

2.1Elhareth Eben Hammam communicated this curious anecdote:

No sooner had the amulets, by which children are shielded from a malignant Nature, been removed from my neck, and replaced with the turband that marks the young man, than I began to frequent the lodging-places of literature, where I intended to acquire such polish as might avail me in polite society, and to amass a store of knowledge that might maintain me should I find no other means of support. So ardent was my love of letters, and so eager my desire to dress myself in their suit of cloaths, that I omitted no degree of importunity in making myself known to poor scholars as well as to men of fortune and rank, for I was desirous of being introduced to any one, who might impart knowledge, or instill discernment. I continued thus for some time, warmly cherishing a dream of hope, and seeking such improvement as my forwardness could procure.

2.2After my arrival in Hulwán, having brought to the test the society I found there, and reckoned in the scale pompous and shabby alike, I found myself in the company of Abuzeid of Serugium. He was a man of extraordinary mutability, at times giving out that he was of Asiatick royal blood, and upon other occasions that he was a chieftain of the Saracens. Compelled by irresistible necessity, he appeared now in the guise of poet, now in that of gentleman. The disagreeable impression that this lack of candour made upon the mind was however effaced by his extraordinary manner of address, his exuberant talk, his celebrated eloquence, his pleasing attentions, his exquisite flattery, his quickness of wit, his copious learning, and his capacious intellect. So engaging was his conversation, that every one overlooked his disadvantages, and so various his knowledge, that all sought his acquaintance. It must be admitted, that such was the force and vigour of his address, that most were unwilling to contradict him, and that the general eagerness to obtain his complaisance arose from fear of being checked by one of his sallies. Yet being most desirous of increase in my stock, and of the opportunity of consulting a sage, I outstripped all others in cultivating his acquaintance, and was assiduous in my attachment to him. For he was, as a certain poet writes:

A friend, that eased the burden of my care,

And bid the joyful days: Arise, ye fair!

His comforts made he mine, no kin by birth,

That I should ne’er thirst, nor want for mirth.

2.3We continued in this manner for a considerable time, he every day contriving to offer me some instruction or delight, or explaining some matter that I had ill-construed. But Fortune at long last compounded him a Bishop of want, misery, and destitution, which obliged him to quit Chaldea. Thus routed upon the field, and resolved to go once again abroad, he departed on camel-back, with my heart as if on a tether drawn along behind. To any other who afterwards seemed desirous of my familiar acquaintance, I spoke as did the poet, viz:

O hopeful one, that seeks my heart,

Did you not see my friend depart?

And did you, gazing, not despair,

That you might to absent love compare?

2.4For some time after that day I did not see him, notwithstanding all my efforts to discover the giant in his den, and my entreaties to persons presumed able to point me to his lair. I then returned to my native place.

One day, while upon a visit to our considerable library, that served as a meeting place for men of letters, whether of the town, or from abroad, there entered a man of unshorn beard and slovenly appearance, who, upon saluting the company, sat down upon the ground, in the back row of spectators. After a short pause he began to shew his powers.

Addressing himself to his neighbor, he asked: What book is it, sir, that you turn over? It is, he replied, the poems of the celebrated El-Bohtoree.

And have you met, sir, with any verses you think are particularly fine?

I have (said the man). These lines:—

If Rubies, loe his lips be Rubies found,

If Pearls, his teeth be pearls both pure and round.

It is a very pretty likeness.

2.5To this, the visitor replied: O brave! What strange want of taste is this, sir, that should cause you to mistake swelling for substance, and cold ash for glowing embers? For how can that verse compare with one, that combines the several similitudes of lips and teeth:-

Rubies, Cherries, and Roses new,

In worth, in taste, in perfette hew:

Which never part but that they showe

Of pretious pearl the double rowe.

2.6The company greeted these verses with approbation, and begged the stranger to recite them once more, that they might take them down. He was then asked, whose they were; and whether their author was alive, or dead? O, gentlemen, he replied, I must tell the truth, for I love nothing so much as veracity. The verses are my own.

The company, suspecting him of imposture, shewed its perplexity. Apprehending the reason for their uneasiness, and fearful of injury to his reputation, he immediately recited from the Alcoran: “O true believers, carefully avoid entertaining a suspicion of another, for some suspicions are a crime.” Then he said: I perceive, gentlemen, that you are connoisseurs of poesy, and criticks of verse. Mankind has agreed, that the purity of any mineral is shewn by fire, and likewise any claim must stand the test of a trial, by which superiority of parts and knowledge will necessarily appear. The proverb says, The proof of the Pudding is in the eating. I have spoken plainly; you may oppose me as you please.

2.7One of the company said: I have, sir, an uncommonly ingenious verse, one superiour, I believe, to all others of its kind. If us you would persuade, pray outmatch it:—

Oh teares, no teares, but showers from beauties skies,

Making those lilies and those Roses growe.

The stranger said: I think, sir, I can make a better. Then he extempore produced the following:

Alas I found that she with me did smart:

I sawe that tears did in her eyes appeare:

I sawe that sighs her sweetest lips did part:

And her sad words my sad dear sense did heare.

For me, I weep to see Pearls scattered so,

I sighed her sighs, and wailed for her woe.

2.8These verses, and the uncommon rapidity of their composition, produced a fine impression on the company, which declared itself assured of his veracity. Now sensible of their approbation, and gratified by the marks of their esteem, he said: Pray let me complete my poem for you. He cast his eyes downwards for a moment, and then said:

I sighed her sighs, and wailed for her woe:

Yet swamme in joy such love in her was seene.

Thus while the effect most bitter was to me,

And than the cause nothing more sweet could be,

I had beene vext, if vext I had not beene.

The company, thus conceiving a very high admiration of his powers, favoured him with expressions of the greatest respect and honour, and undertook to mitigate the shabbiness of his dress.

2.9Our narrator resumed his account thus:

The superlative action of the stranger’s wit, and the animated glow of his countenance, prompted me to examine him more closely; and, upon minute study of his particulars, I perceived that he was my friend from Serugium, his hair now white with age. Delighted to have found him again, I ran up to him, took him by the hand, and exclaimed, Pray, sir, what has befallen you, to thus whiten your hair, and so transform your countenance, that I was at pains to recognize my old friend? He replied:

Year chases year, decay pursues decay,

Still drops some joy from with’ring life away.

Fate! snatch away the bright disguise,

And let thy mortal children trust their eyes.

Hope not life, from grief or danger free,

Nor think the doom of man reversed for thee.

Hide not from thyself, nor shun to know,

That life protracted is protracted woe.

But long-suff’ring patience calms the mind:

Pour forth thy fervors for a will resign’d.

Then he rose and departed, taking our affections with him.