Читать книгу Impostures - al-Ḥarīrī - Страница 37

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

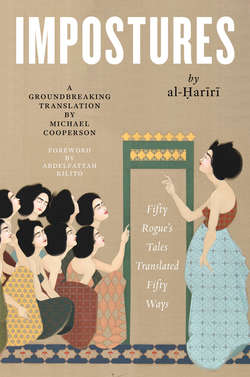

Notes

ОглавлениеThe original is called al-Kūfiyyah, “Of Kufah,” referring to the Iraqi city, but also to the Imposture of that name composed by al-Ḥarīrī’s predecessor al-Hamadhānī. For a comparison of the two see Kennedy, Recognition, 262.

“Sahban” in §5.1 is Saḥbān, a proverbially famous orator, apparently a contemporary of the Umayyad caliph al-Walīd I (r. 86–96/705–15), but otherwise practically unknown as a historical figure (see Fahd, “Saḥbān”). Philip Kennedy suggests that in the companions’ assumption of superiority to Sahban is “a warning about rash inadvertence” (Recognition, 261) especially in view of how the episode ends.

Abū Zayd’s poem in §5.2 consists of half-length lines with a single rhyme. The rhyme is double r, which allows him to use a number of unusual verbs that to my mind produce a comical effect. To approximate it, the translation uses a very constrained English light-verse form, the double dactyl—actually, two double dactyls. This form consists of two stanzas of four lines each; the first three must be in dactylic dimeter and the fourth a single choriamb. The first line of the first stanza must be nonsense and the third line of the second stanza must be a single word. (I have ignored an optional constraint, which is that the second line should mention only the subject of the poem.) My use of the form is slightly anachronistic, as it was invented (by Anthony Hecht and Paul Pascal) in 1951, ten years after Woolf’s death.

Section §5.5 contains the first of many allusions to the story of Moses (for an analysis of which see Kennedy, Recognition, 267–70, 272, 276). For “the mother of Moses” I have supplied Jochebed, from Exodus 6:20 and Numbers 26:59. The name does not appear in al-Ḥarīrī’s Arabic or in the Qurʾanic tellings of the Moses story. But using it allowed me to avoid the awkward “the heart of the mother of Moses” in English.

The English of the poem in §5.7 is based on the form of Arthur Guiterman’s “Philadelphia,” from The Lyric Baedeker (1918), cited in Hollander, American Wits, 7–9.

Regarding the relationship between Abū Zayd and his son (whom we may for convenience call Zayd), Abdelfattah Kilito has argued that Zayd’s insistence that he owes nothing to his father parallels al-Ḥarīrī’s wish to do away with his figurative father—namely, al-Hamadhānī, author of the first Impostures (al-Ghāʾib, 46–47). Katia Zakharia argues rather that the attenuated relationship between Abū Zayd and his son amounts to an argument for the superiority of another kind of relationship, that of teacher and disciple (Abū Zayd, 171–79).

I have taken the phrase “hind-locks grew grey in the dawn” (§5.9) from Chenery, Assemblies, 131. “Cash” does not appear in Mrs. Dalloway, but the OED dates it to 1811.

In later episodes, Abū Zayd will appear with a wife and a son—or, at least, with women and children identified as such. His claim here that “barrah s made up and so is zayd” (§5.10) is, therefore, no more believable than anything else he says. The English form of the poem is based on that of the third stanza of Don Marquis’s “mehitabel s extensive past,” from archy and mehitabel (1927), cited in Hollander, American Wits, 22. In Marquis’s work, the use of lowercase letters follows from the conceit that the poems are the work of a cockroach who cannot reach the shift key while typing letters (Hollander, American Wits, xxiii). “Kumayt” is al-Kumayt (d. 176/743), a poet renowned for praising both the Umayyads and the Alids—an odd choice, as the two great political families were deadly enemies.