Читать книгу 8000 metres - Alan Hinkes - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 SHISHA PANGMA

8046m, 1987

Snow was melting in a small pan over a mini gas burner. Steve Untch, my 6'5" American climbing mate, was doing his best to relax, despite being crammed into the little space remaining in our tiny bivvy tent. Close by in another tent, Jerzy ‘Jurek’ Kukuczka and Artur ‘Słon’ Hajzer were also brewing up. We were at around 6500m on Shisha Pangma and the purring stoves and steaming water heralded refreshment. I was in my element and where I wanted to be, in the Himalaya on an 8000m peak. As I contemplated the warm mug of tea, all thought of danger was washed to the back of my mind.

Abruptly, I was snapped out of this blissful reverie by an ominous, alarmingly loud thud and portentous rumble. Suddenly it was ‘action stations’. There was a great cacophony of yelling in both English and Polish, and I heard Artur and Jurek screaming, ‘Avalanche! Run! Get Out! Avalanche! Come On! Avalanche!’

I pushed the stove out of the door and the precious water spilled over the snowy ground as I frantically yanked my boots on.

In the ensuing chaotic melée I felt Steve clambering over me as he desperately tried to squeeze his huge body out of the constriction of the tent door at the same time as Jurek was gallantly trying to drag me out. It would have been comical if it had not been so terrifyingly serious. It felt like being ambushed and having to scramble and dive for cover, yet in a jubilant, mock-heroic way I was enjoying the drama. Gasping in the icy cold thin air, we tumbled down the easy-angled snow slope below the tent as the soft slab avalanche slithered down towards us.

Fortunately the avalanche ground to a halt before reaching our tents and we literally gulped sighs of relief in the rarefied air; it had been a near miss. When we had all recovered enough to stop blaspheming, I thanked Jurek for his selfless bravery in helping me out of my tent when he could have scurried away. It was a brutal baptism and a great revelation. I now clearly understood that I was not just out for a jolly jaunt with the mountaineering legend Jerzy Kukuczka. Escaping the avalanche heightened my senses and reminded me that I was in a highly hazardous, unforgiving environment. I learned a lot about how to stay alive in the Himalaya on this expedition, especially from Jurek and Artur, and it was to stand me in good stead on many future trips. Ironically, and to my great sadness, Jurek was killed only two years later on the South Face of Lhotse.

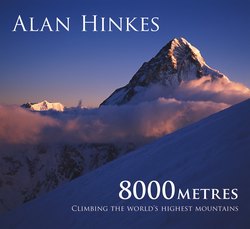

The North Face of Shisha Pangma, from the Tibetan Plateau at 4500m. My new route in 1987 took the central gully line, slanting right-to-left up the face, to the notch in the ridge before the prominent central summit.

We had travelled out to Tibet – a mystical, elusive country – and Shisha Pangma seemed an obscure and enigmatic mountain. I was part of a post-monsoon Polish international expedition, organised by the Katowice Mountain Club. I had effectively served an ‘apprenticeship’ climbing and learning how to survive on 5000m and 6000m peaks in both the Andes and the Himalaya and was now embarking on an adventure to tackle this giant peak with some of the best high-altitude mountaineers in the world. The audacious plan was to attempt two 8000m peaks in succession – first a new route on Shisha Pangma and then the unclimbed South Face of Lhotse, a technical, steep Himalayan ‘big wall’.

We left Kathmandu in late August and headed up the Friendship Highway to Tibet, in the People’s Republic of China. As well as Jurek and Artur, other team members included Wanda Rutkiewicz (Poland), Christine de Colombel (France), Ramiro Navarette (Ecuador), Carlos Carsolio (Mexico) and my climbing partner Steve Untch.

Mud and rockslides caused by monsoon rains blocked the road in many places, and we had to walk most of the way to the Nepal–Tibet border. It was very hot and humid so we often stopped to cool off in the many waterfalls and plunge pools along the way. We soon lost our inhibitions and got to know each other fairly well. The French female contingent fearlessly led the skinny-dipping, rapidly followed by the British and US contingent (Steve and myself). As you would.

Crossing the border from Kodari in Nepal to Zhangmu in Tibet was a curious experience but uneventful. We lodged in the so-called best hotel in town, a scruffy concrete multi-storey building. The TVs did not work and the en suite bathrooms in each bedroom were not plumbed in. Instead there was a squalid porcelain-tiled communal toilet room with a slit in the floor and a big stick to poke the solids down. There was no dining room in the hotel but further up the street a ‘restaurant’ perched on the edge of the Bhote Khosi gorge served palatable food and excellent bottled Chinese beer. To our amazement, after each course most of the plates, the left-over food and all the empty bottles were thrown out of the window into the gorge. Looking down we could see a huge pile of broken bottles and rubbish.

We travelled by Land Cruiser to a roadhead base camp at 5000m, stopping at villages such as Nyalam for a few days’ acclimatisation en route. The Tibetan Plateau was a complete contrast to the hot, humid Nepalese lowlands. Here it was clear, bright, sunny weather and sunburn was a problem, although the nights were icy cold. We hired yaks to take us up to 5900m and the nomadic yak herders arrived to meet us as if by magic, emerging from the barren Tibetan wilderness. Exuding an aroma of smoky yak excrement tinged with rancid yak butter, they certainly looked like proper Tibetans, with jet-black, shiny, plaited hair; most of them were dressed in woollen felt and animal-skin clothes and bootees. To us they were wild-looking characters, but to them we climbers in our modern fleece and Gore-Tex kit must have seemed like peculiar aliens. Unfortunately they also took a fancy to some of our stuff and we had to guard all our kit and supplies carefully.

Jerzy Kukuczka meets nomadic yak herders on the Tibetan Plateau while en route to Shisha Pangma in 1987.

Yak herders’ tent in Tibet with Shisha Pangma behind.

Jurek and Artur planned to climb together, attempting a new route, the traverse of the skyline ridge of Shisha Pangma. Steve and I also had our sights on a new route, lightweight and Alpine-style, just the two of us. We had noticed the obvious diagonal ramp line and couloir running right to left up the North Face, starting from a high altitude basin-like glacial valley at 6900m. Wanda later told me that Reinhold Messner had wanted to climb this line in May 1981 but backed off because of deep monsoon snow. It looked like a steep snow climb at first, reminiscent of a giant steep but easy Scottish gully, such as Number 2 Gully on Ben Nevis. However, higher up it became a lot steeper, icier and rockier before it joined the summit ridge that Jurek and Artur would be climbing. The rest of the team were climbing together up the original route first climbed in 1964. Shisha Pangma was the last 8000er to be climbed, mainly because it was in Tibet and until the 1980s western climbers had been refused access.

By the end of August, using our experience of many other climbs up to 6500m, Steve and I had acclimatised to nearly 6800m when we narrowly missed being engulfed in the avalanche. But 8000m was a new concept. We could hardly have started our summit attempt in a more naïve fashion, planning our Alpine-style ascent without fixed ropes or a tent. I can barely believe we got away with only taking Gore-Tex bivi bags for the final push. We were incredibly lucky and this was the last time I went so high without taking some kind of bivouac shelter.

As so often happens in the Himalaya, the weather broke and we were holed up at Base Camp for over a week in cold, murky conditions with fresh snowfall most days. I didn’t get bored or even frustrated, as there was plenty of vodka and general craic to be had with the expedition team. By mid-September the weather started to clear and, seizing the opportunity, we left Base Camp. Our overloaded, heavy rucksacks, with equipment strapped to the sides, weighed more than 20kg making it an arduous slog up to the bottom of our chosen line, the unclimbed couloir cutting right to left up the north face. Eventually we pitched a tiny bivouac tent in the flattish glacier valley at around 6900m below the north face.

The next day we left the tent behind, intending to collect it on our descent, and started climbing the steepening snow and ice slope in the couloir.

At first, on the easier-angled lower section of the gully, we took turns to break trail. Sometimes the thin frozen crust would collapse and we would sink knee deep into the snow, which was very debilitating.

Upward progress was slow with our heavy rucksacks and as the angle of the slope got steeper, we roped up. The couloir, or gully as it would be called in Scotland, was about grade 3 with steeper sections of hard ice. Technically we were in our comfort zone, but approaching 8000m with our hefty rucksacks we had to dig deep into our reserves of stamina.

The weather remained clear and settled and we climbed until late afternoon before stopping at 7850m to hack out two eyrie-like narrow ledges in the 50° snow and ice slope. These uncomfortable perches were all we had to lie on for the night. We had sleeping bags to snuggle into, but covered only by a thin bivi-bag we were still cold when the temperature dropped to -25°C overnight. I was in charge of trying to melt snow for water, balancing the gas burner and half litre pan on the snow slope. This essential but laborious task was made more difficult by copious waves of spindrift, which would periodically roar down from the summit ridge and engulf us. Spindrift is very fine-grained snow like freezing sand, which penetrates every conceivable orifice. I could not keep the stove going in the cascading spindrift and we had to survive the night on minimal fluids. Several times during the night Steve mentioned that his feet were cold. I massaged and wriggled my toes most of the night. It was more a torture session than rest and recuperation as we suffered and shivered through the freezing bleak night.

Enjoying milky tea with Tibetan yak herders, at Base Camp. In the background are Artur Hajzer and Lech Korniszewski.

Artur Hajzer and Jerzy Kukuczka at Camp 1. Note the debris from a large slab avalanche. This is where, early in the expedition, our two small tents, with us inside them, were nearly wiped out.

As soon as it was light we packed our rucksacks, anxious to leave our tiny, joyless ledges, but we were determined to summit. The final section of the couloir was steep and rocky in places before we broke out onto the ridge at about 8000m. There we found tracks in the snow left by Jurek and Artur who had climbed their new route to the top the previous day. Seeing the footprints in the snow allowed us to be less anxious, as we now had a trail to follow, however the climbing still needed concentration and we could not relax. It was no bimble. We were on a narrow, airy ridge and on both sides there was a thousand metre drop – no place to become complacent.

Steve mentioned his cold feet again, but wanted to push on. I continued scrunching and wriggling my toes at every gruelling step. We toiled up a steep knife-edged snow arête to the Central summit, from where a long and beautiful snow ridge stretched for over a kilometre to the main summit. It was getting late in the day. We were tired, bordering on exhaustion after climbing difficult technical terrain since dawn, but somehow we knew that we had enough in reserve to reach the summit. We pushed on, following Jurek and Artur’s tracks in the snow. It was nice to think that Jurek had climbed his final 8000m peak.

Working our way along this ridge, all above 8000m, we knew that we would have to retrace our steps in order to descend; yet it never crossed our minds to cut down early and forgo the summit. We had to reach the highest point of Shisha Pangma. It is what mountaineers do.

When I reached the top I remember sitting down in the soft snow as Steve came up. The evening light was turning the snow a shade of orange, and one side of the ridge was already in shade. After a few photos Steve set off down and I soon caught him up. As we dropped down off the ridge, descending onto the open face of the original 1964 route, the light was fading and we had to struggle down in the dark with dim head torches whose batteries were fading fast. This was in the days before modern lithium batteries and LED head torches. Later that night we found our bivi-tent and I managed to melt some snow for water. It had been a debilitating 48-hour push. Steve removed his boots to find that his feet were swollen and dark purple. I recognised it as deep frostbite, but tried not to alarm him. There was no point in warming his feet at this altitude, which would cause extreme pain and make it even more difficult for him to climb down. Nevertheless, I knew that he had to get down quickly, as this was serious frostbite, needing intensive medical attention.

At 6800m, carrying a huge rucksack that weighs over 20kg. I am moving up to the final bivouac, ready for an Alpine-style first ascent of the Central Couloir on the North Face. The line of the route is visible behind. My head is covered to prevent sunburn.

With some effort we made it to Base Camp 20 hours later, where the experienced Polish doctor Lech Korniszewski expertly tended to Steve’s now blackened toes and purple feet. Steve was a big strong 6'5" ex-US Army Master Sergeant but he cried in pain unashamedly as his feet were re-warmed. There was no helicopter to get Steve back to Kathmandu, he had to suffer the ordeal of being carried part of the way, and at times hobble agonisingly on his heels. Once back in the US he had several toes amputated from each foot.

My feet and toes were unscathed. Perhaps I had put more effort into rubbing my feet on the comfortless bivouac ledge, when we had slept out in the open at nearly 8000m. My motto is that no mountain is worth a life, coming back is a success, and the summit is only a bonus. Neither is any mountain worth a digit and I still have all my fingers and toes. Maybe Steve was just unlucky; he did have size 14 feet.

Steve was one of the finest people I have been on a mountain with. He was gallant, selfless and good humoured, all qualities that are essential when you feel exhausted and need to find the inner strength to carry on. Seven years later Steve was courageously helping an injured climber down K2 when a rope snapped and he fell to his death. He was an unsung hero and always ready to help others. Tragically it cost him his life.

Steve Untch awaits a brew in a precarious bivouac on a tiny ledge, scraped and dug into the snow slope above 7800m. I was using the stove to melt snow for drinks. A night in the open at such an altitude is a harrowing experience, and this is probably where Steve started to get frostbite. Later, back in the US, his toes were amputated.

The expedition to Shisha Pangma was a great success. Most of the team climbed the original 1964 route to the top, including Wanda Rutkiewicz, Ramiro Navarette, the first Ecuadorian to climb an 8000er, and Carlos Carsolio, who went on to climb all 14. Steve and I had climbed a new route, perhaps innocently using 6000m peak tactics, but we had got away with it, albeit with Steve’s frostbite. But more importantly, ‘Jurek’ Jerzy Kukuczka climbed his last 8000m peak in fine style, by a new route, with Artur Hajzer. We had a celebration in Base Camp, fuelled by Polish vodka, and then celebrated again back in Kathmandu. Jurek went back to Poland as a national hero, the second person after Reinhold Messner to climb all 14 8000m peaks.

It never entered my head that one day I too might climb them all. At that time only two mountaineers had ever achieved this ‘grand slam’. More people had walked on the moon, so it seemed almost unattainable. I just wanted to continue climbing and experience the challenge of giant Himalayan peaks.

After a few days in Kathmandu most of the Shisha Pangma team went home, and I set off with Artur Hajzer and Carlos Carsolio to attempt the huge unclimbed 3000m Big Wall of Lhotse South Face.