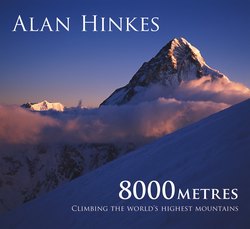

Читать книгу 8000 metres - Alan Hinkes - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3 CHO OYU

8201m, 1990

Categorising any 8000m peak as ‘easy’, or referring to an ‘ordinary’ or ‘normal’ route to the summit, is a contradiction in terms. There is nothing easy or normal about any 8000m mountain. Each of the 14 giants represents a serious undertaking, with different characteristics, dangers, difficulties and local weather patterns, and none should be underestimated. However, Cho Oyu is generally regarded as the easiest and safest of the 14 and to safeguard the climb rope is fixed along the best route. It also has less avalanche and rock fall danger, fewer steep slopes and relatively easy access from Tibet.

Squat rather than pointy, Cho Oyu is a giant, snow-plastered whaleback, a huge Thunderbird 2 of a mountain but as impressive as any other 8000er, with a vast presence. Once fixed ropes are in place on the steeper sections it is a relatively straightforward ascent and the technical climbing difficulties are minimal. Unlike a lot of 8000ers there is no tricky, exposed final summit ridge to fall from – it has a large undulating summit plateau. The final section is like an extreme altitude fell walk to the summit. Cho Oyu attracts a number of teams every year and a well-marked route to the summit is created, making it a favourite for expeditions. It is a good first 8000er to attempt and is regularly guided.

Cho Oyu, sixth highest mountain in the world and possibly the easiest and safest 8000m peak… although there are no easy or safe 8000ers.

Cho Oyu was to be the first of a double bill of two 8000m peaks in one season. We would climb Cho Oyu then go directly to Shisha Pangma, driving across the Tibetan Plateau. It almost felt as though we were using Cho Oyu to acclimatise. I was happy that we had gone to Cho Oyu first as I had already climbed Shisha Pangma. The original plan was to climb a new route on Cho Oyu and ensure all members of the L’Esprit d’Equipe climbing team reached the top together although I realised that our leader Benoit Chamoux would probably have an agenda to make sure of the summit himself, thus moving closer to completing all 14 of the 8000ers.

Tingri, a stark and dusty village at 4300m on the arid Tibetan Plateau. Chinese development has seen the village expand since this photograph was taken in 1990. When I was last there coal was being brought in by truck from Chinese coal mines, to burn on stoves instead of dried yak dung. Coal gives a hotter and cleaner fire than dung and the increase in the village’s population means the yaks can no longer keep pace with demand.

After a team launch in Paris, we flew to Kathmandu to organise the expedition kit before heading up the Friendship Highway north through Nepal to Tibet. Thankfully the road was free of landslides and we were able to drive all the way up to the Kodari Zhangmu border crossing and up to the Tibetan Plateau. I knew the road well by now, having been along it several times on expeditions to Tibet, such as Shisha Pangma with Jerzy Kukuczka and Menlungtse with Chris Bonington. To save time and money, as everyone had to pay a daily fee for each day they were in Tibet, Benoit insisted on pushing straight on to Tingri, high on the Tibetan Plateau at 4300m. Tingri is a dirty, bare, dusty, inhospitable mud-walled village. Imagine Clint Eastwood and the film High Plains Drifter, in brown and grey dust and yak dung. It’s usually a good idea to stop for a few days in Nyalam, a thousand metres lower down, for the chance to acclimatise gradually and safely. Going too high too quickly causes serious acute mountain sickness (AMS) leading to cerebral and pulmonary oedema, which can rapidly be fatal.

Benoit Chamoux and a friendly Red Guard of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army in Tingri.

I was not happy about going straight up to the Tibetan Plateau. On previous expeditions I had always had an acclimatisation stopover in Nyalam for two or three nights, which adds to expedition costs and time, but helps prevent AMS. Benoit often seemed like a man in a hurry, perhaps because he had to live up to his reputation as the fastest man to climb K2. I had experienced the effects of going too high too quickly before and it is very unpleasant. Pain sears through your head, which feels like it might explode, and lethargy sets in as though you have flu. All that speed was an unnecessary risk in my view. However, Benoit was the leader, he made the decisions and he insisted that we would be fine.

Just as I had feared, almost as soon as we reached Tingri I started to feel nauseous and unwell. I developed a pounding, burning headache, which would not go away. Paracetamol and aspirin had no effect. In the end, the team decided to put me in a Gamow bag, which was, at the time, a new piece of first aid equipment. Essentially, it is a big nylon coffin that acts as a mini-hyperbaric chamber. Pressure is built up within in an attempt to fool the body into thinking it is a couple of thousand metres lower down. One of the Italians had also gone down with altitude sickness so we took it in turns to disappear inside the horrible bag. It didn’t seem to do much for my splitting headache and I felt that the only cure was to descend to a lower altitude. A jeep to take the two of us to Zhangmu on the Nepal border would be expensive and taking two of us out of the expedition for three or four days would affect Benoit’s plan for us all to summit together. Thankfully, Benoit started feeling the altitude badly too, so the three of us were driven down to benefit from the thicker air of Zhangmu. There, I immediately recovered. We spent a couple of nights at the much lower altitude, resting, drinking the odd bottle of Chinese beer, eating and gently exercising before driving back to Tingri, this time with another stopover, in Nyalam.