Читать книгу 8000 metres - Alan Hinkes - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 MANASLU

8163m, 1989

In December 1988 my telephone rang. I lifted the handset and a man speaking with a Gallic accent introduced himself as Benoit Chamoux. I was aware of this well-known French mountaineer; he had made his name with a very fast ascent of K2 and had summited several other 8000ers, openly declaring his intention to be the first Frenchman to climb all 14. He was developing quite a reputation among the international mountaineering community and was fast becoming a household name in France. My first reaction to his French-accented voice inviting me to the Himalaya was that it was a hoax call, so I told him where to go and put the phone down. It sounded too good to be true.

Luckily Benoit rang back and persuaded me it really was him. He wanted me to join his L’Esprit d’Equipe team of European mountaineers sponsored by Bull, a French multi-national computer company. Loosely translated, L’Esprit d’Equipe means ‘team spirit’. This was a unique and well-funded Himalayan climbing team, with the main aim of climbing 8000m peaks.

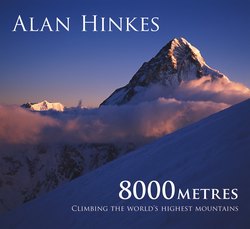

High on the summit slopes of Manaslu, heading for the top.

I met Benoit on Christmas Eve 1988 at Bull’s Paris headquarters. It was soon clear that Benoit’s lucrative sponsorship deal was unlike anything I had come across before. Earlier that year I had been on a Chris Bonington-led expedition in Nepal and Tibet, to ‘Search for the Yeti’. That was a well-sponsored trip with backing from The Mail on Sunday, William Hill Bookmakers, and the Safeway supermarket chain (now Morrisons). It also involved a BBC film crew making a documentary and hoping we might find the Yeti. Along with Andy Fanshawe, I made the first ascent of Menlungtse West, a 7000m peak. Even that well-underwritten, relatively well-heeled expedition seemed impecunious compared to Benoit’s lavish budget. The L’Esprit d’Equipe team members even got a small fee and summit bonus, in addition to all their expenses and expedition costs. Normally I only managed to get a little subsidy and help towards my overall costs for an expedition, in the form of small grants from the Mount Everest Foundation (MEF) and the British Mountaineering Council (BMC). Just occasionally, I was lucky enough to attract sponsorship from a company hoping for some PR, marketing or advertising return. It is more usual for an expedition to demand that your own money be earned, saved and then spent on the trip.

I liked Benoit. He was a professional mountain guide like me and we seemed to click and got on well together. I sensed that we shared a deep passion for mountains and I happily and eagerly signed up as the token Anglo Saxon, or as the French would have it, ‘le rosbif’.

As soon as the Paris meeting ended, I set off to catch the last flight from Paris Charles de Gaulle airport back to Britain. What a great Christmas present, I thought. I could hardly believe it. I now had several fully-funded expeditions to look forward to. And to think I had initially put the phone down on Benoit, thinking it was a mate having a laugh.

I was in a joyful, Happy Christmas frame of mind as I boarded the British Airways aeroplane. The pilot cheered me up even more when he announced his name over the intercom: ‘Good evening, everyone. This is Captain Kirk speaking.’ Everyone expected him to maintain the Star Trek theme and announce that the First Officer was Mr Spock. The roar of laughter must have reached him on the flight deck as he continued his pre-flight spiel, but I suppose he was used to it – he really was Captain Kirk.

L’Esprit d’Equipe required regular commitment. I would travel to France every month, usually to Paris, Chamonix or the Alps. The idea was to keep the team close-knit, train together and bond as well as setting an example for the Bull company employees. Previously Bull had sponsored an ocean-going yacht in the Round the World Race. Benoit decided that a two-day team-building and bonding trip on a racing yacht into the Atlantic from St Malo was a good idea. This was a new and different experience for me, more used to the mountains and terra firma. I had done several sea kayak trips off the British coast, but this was much further out on the ocean. It required teamwork and commitment in an unforgiving environment and I quickly realised that if I went overboard I would be as dead as if I had fallen down an 8000m mountain face.

Porters heading for Manaslu Base Camp pass through the lowland villages of the Marsyandi Valley, during the trek’s early stages. Their loads are suspended on tumplines, or bands, which distribute weight across the forehead. Most carry 25kg loads which are in blue or green waterproof barrels or wicker baskets called dhokos.

The rest of the climbing team was a great bunch of experienced French, Dutch, Italian and Czech mountaineers. It was good to make new friends and practise European harmony. Contrary to many people’s expectations, we all got on very well and enjoyed climbing together as well as our bonding and team-building exercises. English was the common language (or the lowest common denominator?) for everyone. In Nepal, English was spoken rather than French or Italian and, apart from the odd curse, very little Czech was uttered. French was generally spoken in Bull meetings in France and I became reasonably competent at speaking and understanding French, which was a useful bonus.

I felt fortunate to be visiting France nearly every month. I made some great French friends and got to know many delightful, amazing places. France has a wealth of varied climbing areas, and as a team we also canoed, hiked and skied together. I enjoyed the French culture – their food, wine and the French way of life. In the 1980s I did not need to be as politically correct as now and the rosbif’s quips about Agincourt, Trafalgar, Waterloo and Dien Bien Phu were taken in the light-hearted spirit in which they were intended.

The South Face of Manaslu, seen from inside an ice cave on the Thulagi glacier at Base Camp.

Benoit set the agenda for the team, which was all about him becoming the first French climber to bag all 14 of the 8000m mountains (something that would never happen – he disappeared on Kangchenjunga in 1995). At the time, I was just happy to be part of a great team, make new friends and climb some big Himalayan hills. At that point Benoit had eight 8000ers under his belt and had decided that Manaslu would be next, which was lucky for me, as, if we were successful, I would be the first Brit to climb it. However, it was not just a matter of Benoit getting to the top; part of the ethos of L’Esprit d’Equipe was to get everyone in the team up to the summit as a conspicuous display of teamwork.

In March 1989 we set off for the south side of the mountain, which very few people attempt to climb even today, not least because of the difficulties in getting there. Once we had left the last village, we had to hack our way through jungle undergrowth, cutting a trekking path with khukris and machetes. It took several days of hard labour rather than the usual bimble along a well-trodden trekking path before we reached the more open glacial area above the tree line. The arduous journey felt eerie, as we were all alone, well off the beaten track. There were no local villagers, teashops or trekking lodges, no other expeditions and no trekkers. There did not even appear to be any wildlife about – we had probably scared it off as we crashed and chopped our way through the pathless forest. Reinhold Messner had made the first ascent of this route with a Tyrolean expedition in 1972. Since then very few people had passed this way. It was almost virgin territory.

A huge airborne avalanche roaring off Peak 29 towards Manaslu Base Camp. The air blast reached us like a severe blizzard, covering the tents in snow.

Base Camp was a barren spot on the moraine-covered Thulagi Glacier. We cleared and built flat areas like patios for our tents on the rock-strewn ice; some of the platforms had to be quite spacious as we had the latest, luxurious two-metre dome tents to erect. The south face of Manaslu, a massive 600m rock wall, towered above Base Camp and huge avalanches poured off the mountain and its neighbour P29 virtually every day. They would often reach Base Camp as blizzards, dusting the area with a layer of fine snow. It was impressive but also somewhat unnerving, as we knew it would only take a slightly bigger avalanche to wipe us all out.

Manaslu Base Camp after heavy snowfall had damaged some of the tents.

The South Face of Manaslu is a Himalayan ‘big wall’, involving steep rock climbing at high altitude. Pushing out the route on the huge rock face, I found the lead climbing challenging and satisfying. It was certainly no snow plod. We had to fix ropes and, at one point, we rigged up a cableway, like a mini téléphérique, to transport the team’s equipment up the steep rock barrier to the Upper Manaslu South Glacier, nicknamed the Butterfly Valley. This 5km-long glacier-filled valley is like the Western Cwm on Everest, it is exposed to avalanches from surrounding peaks on both sides and leads up to the final summit slopes of Manaslu.

Big wall climbing – 600m of serious technical rock climbing on the South Face of Manaslu.

Just crossing the glacier to the bottom of the big wall from Base Camp was like a giant game of Russian roulette, with massive avalanches frequently scouring the route. It was a scary two-hour trek to the relative safety of the rock face. We had to gauge the threat and decide when the next avalanche was likely before moving; if we had been caught out in the open we would have been wiped out. Once an avalanche goes airborne, you can be killed by the pressure wave, a huge blast of air that forges ahead of the roaring snow like an explosion; large avalanches can completely wipe out villages and flatten forests.

During that two-hour approach to the shelter of the wall, I often felt as though I was on a military patrol, constantly looking for the nearest cover of a big boulder or crevasse in case we came under ‘effective enemy fire’. In that scenario, the enemy was the constant threat of avalanche and rock fall, which was as lethal as any gunfire or mortar attack. It was always a relief to reach the cover and safety of the South Face. Climbing the vertical and overhanging 600m rock face was the key to the ascent, but not easy at this altitude. Overcoming it took nearly three weeks of effort, determined teamwork and technical rock climbing. Higher up in the Butterfly Valley between 5800m and 6000m the steepness eased and the climbing was back on snow and ice, where in addition to the avalanche danger there were hidden crevasses to cope with. As we made our way up the hanging glacier towards the steep snow and ice slope which led to the summit, the atmosphere was excitably amicable. In a curiously masochistic way, we all relished the challenge of ferrying heavy loads higher up the mountain and setting up a camp ready for the summit push. Our training sessions had instilled in us the ‘all for one and one for all’ ethic and we worked together well. Originally Himalayan expeditions had involved a team of many climbers pushing higher and higher up a mountain, establishing and stocking camps with equipment and food. When all the tents were in place, usually only two climbers from the group would make the final summit push. The ethos of L’Esprit d’Equipe, to which Benoit and all of us were dedicated, was to get every member to the top, not only as an obligation to our sponsors but also as an illustration of teamwork. Eventually an assault camp was established at about 7400m, leaving a 750m final ascent to the top.

The Butterfly Valley (Upper Manaslu’s South Glacier). The route went well to the left to the col, avoiding avalanches from the hanging glaciers and seracs on the peak’s summit slopes.

Benoit nabbed a good weather window and reached the summit first, bagging another 8000er for his collection. I was acclimatised, fit and ready for a summit bid with one of the Italians, but we had to retreat as his feet were numb with cold and he was concerned that frostbite was setting in – so we climbed down to warm his toes in the tent. We spent the night keeping as warm as possible, melting snow for water and fuelling up with fluid and calories before making another bid for the top.

Benoit Chamoux and Pierre Royer in Base Camp, satisfied but exhausted.

True rest is difficult to achieve at high altitude, sleep is fitful and fitness deteriorates. We knew that we had to make another summit bid the next day, so prepared and rested as well as we could. Luckily the weather remained clear and settled and we confidently set off for the summit, this time with no cold feet. The final narrow ridge to the summit with a big drop on either side was much steeper than I expected. I could not let my concentration wander, as one trip or slip would send me sliding thousands of feet to my death. I remember the air being crystal clear and very cold, about -20°C. The views were amazing, it was one of those days when it seemed that you could see forever and I felt tremendously privileged just to be there. I managed to get a summit photo of me holding a picture of my daughter, Fiona, who was only a toddler at that time.

The expedition was a great success, no one died and all the L’Esprit d’Equipe climbers made it to the top and back without frostbite or other injury. Bull Computers was very pleased with the publicity and decided to continue the funding. The mountain was first climbed in 1956 from the north side by a Japanese expedition. As an added bonus for me, 33 years after that first ascent, I had become the first Brit to reach the summit.

On the summit of Manaslu, 15 May 1989, holding a photo of my daughter, Fiona. This was my second 8000m peak. I never imagined then that I would go on to climb them all. In this photo she is only a child; by the time I had finished all 14 she was grown up and had her own little boy.

REINHOLD MESSNER

Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner is an icon of almost mythical status. His contribution to mountaineering, especially among the Himalayan and Karakoram 8000ers, is unequivocal. His achievements are a benchmark.

In 1986, he became the first person to have climbed all of the 8000m peaks, one year ahead of Polish climber Jerzy Kukuczka.

Climbing all 14 peaks is a quantifiable and inspirational goal in mountaineering, just as the four-minute mile, first run by a Briton, Roger Bannister, paced by Chris Brasher and Chris Chataway, is in athletics. More than a thousand people have run a four-minute mile since 6 May 1954. So far fewer than 30 have climbed all 14 8000m peaks and it will be a long time before a thousand people have managed it. Running a four-minute mile takes dedication, technique and tremendous effort; climbing all the 8000m peaks requires all of the above but also carries a high risk of death.

Where’s my pint? With iconic Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner, the first person to climb all the 8000m peaks.

Messner pushed the boundaries of stamina and determination as well as overcoming tragedy and setback to achieve success. He is a survivor and has inspired many mountaineers. He broke many psychological barriers during his mountaineering career, not least surviving many days in the death zone above 8000m.

As a young Alpinist I was influenced by his books, his climbing style and his ethics. He is an exponent of climbing fast and light and made daring rapid, solo ascents of big Alpine faces. He held a speed record on the North Face of the Eiger for some years, climbing it in ten hours with Peter Habeler in 1974. In the Himalaya he endured a traumatic descent on Nanga Parbat during which his brother Günther was killed; Reinhold survived the experience but with severe frostbite and had all his toes amputated. Nevertheless he went on to climb all the 8000m peaks.

There is no doubt that Reinhold Messner is one of the world’s greatest ever mountaineers. Distinctive looking, with a thick mane of hair, he is outspoken and has strong opinions on mountaineering and many other topics. I met him at the British Embassy in Kathmandu when he was a Euro MP for the Italian Green Party and we talked as much about European Politics as we did climbing.

Messner has a dedicated mountain museum in the Tyrol and is pretty much a household name in Europe. I have chatted with him at several mountain festivals in Britain and at Buckingham Palace, where we joined a gathering of fellow adventurers. It was salutary to realise that Messner, an Italian, was flattered and honoured to meet our Queen.