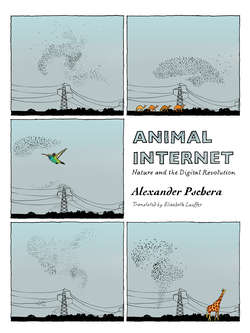

Читать книгу Animal Internet - Alexander Pschera - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

DO NOT TOUCH! THE REPERCUSSIONS OF LOST SENSORY EXPERIENCE

ОглавлениеOur loss of the animal world manifests itself as the loss of our elementary sensory capacity. Beyond the realm of house pets, which have become active participants in our society at this point, there’s no remaining sensory connection where humans and animals can meet. Fundamental physical contact—petting, cuddling, brushing, and milking, but also slaughtering, gutting, cutting—is essential to this relationship. Care and carnage go together. They’re two sides of the same coin. Direct, bloody encounters with the animal world—like slaughtering a rabbit, gutting a carp, or plucking a chicken, which older generations still remember—are viewed today as barbaric acts that few could bring themselves to do, even if they’re not vegetarians. With regard to animals, we are no more than what Hegel called “beautiful souls” who dream of peaceful coexistence while eating factory-farmed chicken. The murder must occur outside our range of perception. Contemporary cooking plays its part with its abstract contortions, transforming a simple piece of raw meat into a dish served in fine restaurants, arranged on the plate like a Kandinsky painting. Meat reaches us as a biomass that is uniform in color and artistically presented, and that’s not allowed to reflect its animal origins, but must instead obey the law of aesthetics. A cultural transformation in the way living creatures are perceived can clearly be seen here. Many foreigners visiting France, for example, may be unnerved by the displays in French butcher shops, where scaly skin may be left on the chicken legs, patches of fur on the rabbits. These last remaining signs of animal life come as visual shocks, although they really should indicate the quality sourcing and naturalness of the meat. But these fragments of the wild that find their way into civilization and consumer society deeply disturb our sensibilities when we set eyes on them.

Why? Because over the last fifty years, an unfortunate change has occurred in the way we raise children that has systematically distanced us from animals. Many of the great natural scientists and nature writers have childhood memories of entire afternoons spent catching animals and collecting flowers. Insect collections and herbariums used to be commonplace features in any childhood room and might serve as the starting point for an expedition into the natural world. Truth be told, if one wants to get close to nature, one must touch it. This is the secret of gardening. And it certainly applies to animals. One who has never torn off the tail of a lizard knows nothing of the reptile’s slippery agility. One who has never sunk thigh-high into a pond’s stinking mire while trying to catch a frog knows nothing of these amphibians’ leg power. One who has never tried to catch a bat that mistakenly flew into the house on a hot summer night and took cover under the bed, knows nothing of how viciously these little mammals can hiss, and what pointy teeth they have. One who has never chased a butterfly hither and thither knows nothing of how unpredictable these insects’ flying maneuvers can be. The secret to animals is revealed only through a sensory, a physical act. To grasp is to understand. A relationship can form only once one has touched an animal’s skin or fur, felt its teeth, smelled its warm excrement in the palm of one’s hand, or destroyed its delicately pigmented wings in a thoughtless move. Only then does the animal leave its imprint on the senses, and thus on the person’s life story, becoming part of that story. And only then is that person prepared to do something for this animal, because now the “it” has become a “you.” It has become a friend.

This reciprocal exchange with wild animals has become impossible in today’s world. Wild animals are foreign creatures that have been recast in a symbolic role, recognizable at best from documentary films or zoos. They live “out there” in the natural world, tolerated by civilization, inventoried by biologists. For most people, concrete contact with wild animals is taboo—unless they submit themselves to the overregulated hunting and fishing system, which has itself now mutated into a type of romantic, overblown pest control. Nature doesn’t belong to us anymore. This is the aim of nature conservancy, which has put strict demarcations in place to protect biodiversity. No one can say who nature belongs to, though—not even those working to protect it. This is because it has morphed into “nature as such,” an abstract construct which society keeps referring to, but that simultaneously demands our utmost consideration. But why should humans care about something that has nothing to do with them, that they are not allowed to touch? It comes as no surprise, then, that for most people, the natural world—even right outside their back door—is something alien that has no bearing on their life. It’s an idea, an image, a cultural phenomenon, a supposition.

Not so very long ago, this was fundamentally different; smell and touch constituted an awareness of nature that is as endangered today as many animal species. Many authors, in whose works nature plays an important part, have described how their sensory contact with nature—which was not infrequently quite dangerous—provided them with a deep understanding of animals. It is worth reading these stories closely, because they illustrate the distance that separates us today from existential contact with nature. In his memoir, Green Branches, a thick compendium of sensory experiences with the natural and animal worlds, Friedrich Georg Jünger, the younger brother of the German author, aesthete and entomologist Ernst Jünger, describes how, as a child, he was able to locate the vipers living in the stone quarry by their “curiously pungent smell” alone. The nose, the olfactory organ, establishes the first, most direct connection to nature. Like hunting dogs, humans pick up traces of animal scents with their noses. This form of approach originated in the distant past of human development. Together with his brother, Ernst, Friedrich Georg Jünger collected all manner of beetles by “knocking, sifting, chomping, prizing off” sections of tree bark. Every form of contact—as reflected in a grand, almost lyrically onomatopoeic repertoire of action words—is employed to get at the animals. The boys’ driving curiosity is not slowed by unknown quantities: “ground and bark mushrooms, rotten fruits, carcasses and excrement were examined; carrion, cheese rinds, and other bait laid out.” The interaction with nature becomes a full-body affair: “In order to be totally unhampered, we undressed and hid our clothes in an alder bush and wandered naked half the day through the marshy meadows and reed thickets that surrounded the water in a wide, green band. To repel the mosquitos, gnats, and horseflies, we smeared the thick, black sludge all over our bodies … Then we hurried with quick steps over the turf of the floating meadow that undulated under our weight, like a calm lake.”

In the foreword of his wonderful book on cranes, zoologist Josef H. Reichholf also tells the story of how he, as a ten-year-old child, stole a young jackdaw from its nest in a church tower and raised it at home. The hunting excursion proceeded as follows: “The jackdaws had been nesting in this tower for centuries. They built nests in the rafters and added layer after layer every year, till one of these towering nests grew too tall and toppled. Fragments of these nests that were full of fecal remains, dust, and the mummies of baby birds that had never taken flight, landed far below on the upper platform … Pretty filthy from all the stuff that had rained down on me—because I inevitably bumped into old nests—but with a screeching baby jackdaw as my haul, tucked away under my shirt, I came back down and slunk away from the church like a thief.”

The humans who feel drawn to nature take it into their possession. They instinctively grasp at it. The beetles end up in a display case, the jackdaw flutters through the aviary, a terrarium is assembled for the slowworm, which may not last longer than three days in captivity if not properly habituated. Living creatures are killed, collected, pinned, or caged. Destruction is not the aim of those who grasp at nature in this way; in fact, quite the opposite applies: they want to join in the natural order as something that belongs there.

I can still clearly remember the first vivarium I had as a child, in which I kept a sand lizard for two days. The vivarium did not have a lid and sat outside in the yard. One morning I discovered the lizard dead, with a deep hole in its back. The creature at once became a fascinating object of close study. The lizard had been killed by a bird. This event revealed the lizard’s vulnerability to me. Danger came from above, it turned out: the reptile’s Achilles’ heel was the blind spot on the neck where the eyes of the otherwise very quick and observant animal did not reach. The lizard was dead, after only two days, and now a new specimen had to be caught. This behavior wasn’t destructive, and it certainly wasn’t wiping out any lizard populations, but it did result in bringing a child closer to nature. It sparked an interest that has endured until today. Making nature one’s own or appropriating nature, which itself primarily obeys the law of the jungle, is not an act of annihilation, but one that engenders respect. It enables people to study up close what would otherwise remain abstract. Children today can no longer experience this nearness. What are the reasons for this loss of sensory experience?

A central problem stems from the fact that modern science and its teaching systematically undermine the value of the visible. This has led to the devaluation of the perceptible world, as opposed to unseen structures. The ideology of the invisible has especially taken its toll in schools. Biology instruction no longer covers practical zoology, concentrating instead on abstract connections. Instead of species identification, teaching now focuses almost exclusively on molecular biology and genetics. The result is the loss of openness to phenomena, the atrophy of human senses and sensory nature. The tangible world is being degraded, as opposed to the unseeable world of molecules and enzymes, the structures that constitute our world. Over fifty years ago, in her book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt already drew attention to the danger of sensory experience disappearing from the scientific process, the roots of which she traced back to Cartesian thought. In doing so, she analyzed the connection between the loss of fundamental common sense and the consequent effect on society and its political discourse, based now solely on abstract deduction, rather than on visible reality: “This faculty the modern age calls common-sense reasoning; it is the playing of the mind with itself, which comes to pass when the mind is shut off from all reality and ‘senses’ only itself. The results of this play are compelling ‘truths’ because the structure of one man’s mind is supposed to differ no more from that of another than the shape of his body … The Cartesian solution of this perplexity was to move the Archimedean point into man himself, to choose as ultimate point of reference the pattern of the human mind itself, which assures itself of reality and certainty within a framework of mathematical formulas which are its own products.”

Also contributing to humans’ estrangement from their natural surroundings is the myriad of technological aids that permeate daily life, the extensive use of media, the intense allure of the digital world. Nearly every recent study of the relationship between humans and nature shows that the high level of digitization and virtualization in our society is to blame for our diminishing connection to the natural world. The Internet, smartphones, and GPS systems are made out to be the causes of a global acceleration obscuring the rhythm of nature. The flood of stimuli in the digital world has brought about a deadening of the senses. And truly: we are scarcely able to perceive nature or move freely within it anymore. Natural space now serves as little more than a stage for athletic activity. We rely on technological aids to the extent of unlearning how to read nature’s signs and orient ourselves according to them. And every hour spent staring at a computer screen is another hour not spent out in the fresh air.

There is a further reason for this estrangement that is by far the most telling. Because even without the distraction, indeed the reeducation brought about by technological devices, it would be very nearly impossible today to explore the natural world inhabited by wild animals. Those places that remain biodiverse, removed, and wild are now mostly inaccessible. The nonurbanized world is demarcated by countless boundaries and governed by restrictions. Nature preserves alternate with land trusts, while between them stretch exhausted fields that cannot support much more growth than dandelions. Hobbies that were once commonplace and established the very basis of a human interest in nature can now be considered criminal: foraging for mushrooms, picking flowers, catching and observing animals, filling butterfly display cases and curating insect collections. This all used to be a self-evident part of a creative way to make nature one’s own, a way for humans to immerse themselves in natural space. But now going after a cabbage white butterfly or slowworm can result in a hefty fine for the perpetrator. These days, parents planning a butterfly collection or catching a lizard for their child’s terrarium are engaging in illegal activity. But a sense of freedom, or even anarchy, is a fundamental part of discovering nature. For children, nature is the antithesis of the world of school and parents. Animals are ambassadors of a different, freer life. Forming a connection to them amounts to breathing the air of a better world. Contemporary nature conservancy has managed to morally recast this refuge and poison the air of freedom. The Eleventh Commandment reads, “No Touching!” And those who do so despite the warnings suffer a guilty conscience, given the extent of our reeducation. We can all easily assess this in ourselves.

The result of this general prohibition on touching manifests itself in younger generations as a massive deficit in knowledge of biological connections, plants, and animals. It comes as no surprise that the ability to identify wild species is in rapid decline, as many recent studies show. Most people don’t even know what kind of animals live in the woods beyond their own backyard. They can no longer identify birdcalls or read animal tracks. Even common native species like buzzards or badgers are no longer recognized. The loss of connectedness to nature has become pathological. There is even a condition called “nature deficit disorder” that is characterized by this very disorientation in natural surroundings. Far from an alarmist horror scenario, Richard Louv’s successful book Last Child in the Woods depicts the bitter reality. Louv recently concluded, apodictically, “The more high-tech we become, the more nature we need.” According to the author, the result of this growing tech dependence is a clinical condition that can be combatted only by systematic greening efforts and regular encounters with nature. Rather than the World Wide Web, Louv recommends what he calls the “Web of Life,” as part of a therapy program he has designed and conveniently made available for purchase.

However exaggerated this therapeutic approach may be, Louv is justified in his diagnosis. The hypothesis suggesting humans’ fundamental distancing from nature is empirically substantiated. The 2010 annual report of the Children & Nature Network determined that “children’s recognition of wild species continues to decline.” This can be traced back to the fact that for years, visitor numbers at U.S. national parks have been in steady decline. The numbers have decreased by 7 percent between 1997 and 2010. Another study identifies the clear connection between declining numbers at national parks, on one side, and the increase in use of electronic gadgets, on the other: “This decline, coincident with the rise in electronic entertainment media, may represent a shift in recreational choices with broader implications for the value placed on biodiversity conservation and environmentally responsible behavior.”

The statistics are clear: America’s children today spend over fifty hours a week with electronic devices and less than one hour outdoors. Just one generation earlier, children spent at least four hours a week out in the fresh air. Children who grow up biased toward electronics will not grow into adults concerned with nature conservation—and it’s because they feel ambivalence toward nature or, more dramatically, because at some point, they won’t even know what could possibly be meant by “nature.”