Читать книгу Animal Internet - Alexander Pschera - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

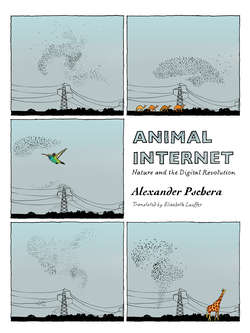

THE TRUTH BEHIND THE PICTURES

ОглавлениеAnimal pictures allow us to lose sight of the real disappearance of animals that is currently under way and gaining speed, as recent studies show. It took humans 23 million years to eradicate about 10 to 20 percent of the animal species on the planet. According to the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Index, the earth has lost half its animals species in the last forty years. In the meantime, human destructiveness has intensified to the point where, if we continue at our present pace, we will have wiped out a further 20 percent of species in the next thirty years—plants, insects, spiders, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals. One does not need to be a math genius to comprehend the catastrophic ramifications of such a rapid loss of biodiversity. Half of all known species now face extinction. The factors responsible for this are the destruction of habitat, pollution, human exploitation of natural resources, climate change, invasive species, epidemics, wars, and geopolitical transformations.

Current studies show that half of the North American bird population is endangered. This includes both urban bird species like the Baltimore oriole and rufous hummingbird, and those found in the wilderness, like the common loon and bald eagle. A report published by the Audubon Society states that 314 species would face a massive decline in numbers, should global warming further worsen. This is cited as a key factor in extinction rates, because changes in temperature force animals from their native habitats. The bald eagle was once the poster child for American conservation efforts. It is now poised to lose up to 75 percent of its population by 2080. Between 1900 and 2010, destruction of freshwater habitat in the United States advanced at a rate 877 times faster than in prehistoric times. Most recent estimates assume that the rate of extinction will have doubled by 2050. Between 1898 and 2006, the United States lost thirty-nine species and eighteen subspecies. Researchers now predict that a further fifty-three to eighty-six species will have gone extinct by 2050. The causes all stem from human interference with wildlife habitat. Freshwater fish are a good indicator of general extinction patterns, because wetlands are home to a broad diversity of species. Fish extinction is just the tip of the iceberg. Mussels and snails are dying out even more quickly.

The United States is typical of the current global trends of animal extinction. In order to get a feel for these fatal developments threatening the animal world, Edward O. Wilson, who dedicated his entire life to the study of ants, performed a quick but telling calculation: the current understanding is that over half the life forms on Earth live in the tropical rainforest. Every year, 1.8 percent of the rainforest is destroyed, which translates into a loss of 0.5 percent of the world’s species. If the rainforest is home to 10 million organisms, which is a conservative estimate, then fifty thousand species are lost per year, 137 per day, six per hour. And this estimate is not even the worst-case scenario, because this calculation of extinction rates is limited to the connection between surface area and species. Further negative influences, pollution, disruption, and the introduction of foreign species are not factored into the projection. Prospects are similarly desolate in other diverse habitats, such as coral reefs, river systems, lakes, and wetlands. There is, of course, enough wilderness left on Earth that new animal species are still being discovered—and not just bacteria and inebriates, but mammals, too, like the Andean olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina) and the Flores giant rat of Indonesia, which typically live in remote areas. But these are rare exceptions to a sad rule. At the same moment researchers gleefully add the odd new species to the register of planetary inhabitants, the overall development of their own species results in whole pages of that register being wiped out. Should the current trend continue unhindered, by 2030, habitats for apes will have been destroyed by 90 percent in Africa, 99 percent in Asia. The earth is becoming a planet of dying apes.

When faced with the logic behind this fall to ruin, it is hard to remain optimistic. This is especially the case when one considers the ineffectiveness of the animal protection initiatives that heads of state so often sign in order to gain popular appeal. It has reached the point where one could justifiably adopt the defeatist stance of the “nature pessimist,” who considers the earth’s fate to be sealed, since the course of extinction is no longer stoppable. For example, there are far too few tigers and apes left for these animals to muster the strength to survive and reproduce, should their current situation worsen further. Ground cover has grown too thin. We may be the last or second-to-last generation to wander the earth with wild, free-ranging mountain gorillas or orangutans. We may need to accept this logic of extinction as the flipside of an increasingly technological world in which the Western standard of living is the guiding light that everyone wants to follow—and should.

Despite numerous sweeping measures—one need look no further than the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, or the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2002—the facts indicate that not only is the rate of extinction on the rise, the earth’s general health is deteriorating. It is clear today that every environmental problem discussed in Rio in 1992 has worsened significantly in the intervening twenty-five years, rather than improving. Between 2000 and 2011, worldwide carbon dioxide emissions raced unimpeded from 24.9 to 34 billion tons, thereby achieving a record high. The world is currently losing thirteen million hectares of forest yearly. Desertification is also advancing unchecked.

The naïveté required to envision going “back to nature” in the face of this dynamic of destruction is astounding. The natural world to which humans like to think they could return, in turning their backs on civilization, no longer exists. In fact, it never has. The state of nature is not some static construct; rather it is caught in a system of perpetual change, continually reshaping itself to accommodate the conditions affecting nature. The image of a realm free of all human influence has been desirable since the days of Rousseau, because it promises liberation from the shackles of present concerns and suggests a return to innocence. Today’s way of thinking about natural habitats and the praise of wilderness without humans is still informed by this push “back to nature.” Yet the concept remains utopian, an idealized cultural product created by humans—and later, we will see how our conception of ecology and environmental protection is defined by this culturally derived notion of a natural world at odds with civilization, and how we are missing the target of effective conservation as a result.

The question needs rephrasing. Not, “Can we return to nature?” but rather, “Can we view nature differently?” and, “What will happen to us, the viewers, once we have seen nature as never before?” There is no way back to nature. What may well be possible, however, is the emergence of a new image of nature—an image that is concrete and stimulates the senses, that breaks through the abstraction and doesn’t just give the illusion that everything is fine and under control, not unlike a parakeet chirping happily in its cage on the windowsill. This new image would then be used in establishing a new paradigm for encounters with nature. And it is here that the Animal Internet begins.