Читать книгу Animal Internet - Alexander Pschera - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FORMS OF COMPENSATION IN THE CONTEMPORARY AWARENESS OF NATURE: BIRD-WATCHING, ZOOS, HOUSE PETS

ОглавлениеNow it can’t be said that we’ve lost all interest in animals. In fact, one almost gets the sense that human involvement with nature is greater than ever before. Nature observation has become an expensive hobby, zoos are logging record visitor counts, and there have never been as many house pets on Earth as there are today. Upon closer inspection, however, our obsession with animals reveals itself to be an obsession with ourselves. These are forms of compensation that, rather than bridging the rift between humans and animals, only serve to deepen it. This compensation puts nature at a distance and makes it something abstract, something untouchable.

The concept of noli me tangere again applies here. Touching is supplanted by viewing. Schoolchildren learn to recite the stubborn mantra of “just look, don’t touch.” Adults then carry on the “just looking” rule to its consummate end in the newly popular sport of bird-watching. The semiprofessional bird-watcher spends a small fortune on “optics,” as they are called; in other words, on the binoculars and spotting scopes. This is a paradoxical investment in an instrument that separates the bird-watchers from nature, keeping them at a distance while giving them the impression—thanks to longer focal lengths and higher resolutions—of getting closer than ever to the animals. Bird-watching illustrates the dilemma at the heart of the postmodern awareness of nature. An imagined closeness is created that actually amounts to the most profound separation.

The bird-watcher is fundamentally solitary in relation to the animals. The solitude is reflected in the birder’s activities that, however driven by the hobbyist’s zeal, ultimately comprise little more than counting individual animals and collecting glimpsed species. Both activities are forms of a catalogic aesthetic that subordinates nature to the logic of the observer and that focuses more on the observing subject than on nature. Ornithologists uphold an aesthetic biophilia that is long established among the educated and that remains shaped by structural categories dating back to Goethe and the Enlightenment. Nature serves here as an intellectual refuge for the subject in search of self, jaded by civilization, who ultimately finds salvation in the purity of natural experience. The current bird-watching trend serves as a good example of the cultural transformation that has changed what was once an existential tie between humans and animals into a reactive stance of pure observation.

Ornithology is one form of compensation for a modern society that has lost touch with nature. The second form of compensation is the aesthetic reconstruction of animal freedom, as found in zoos and safari parks. More and more money is being poured into modeling deceptively realistic nature dioramas. These reconstructions of freedom entail the principle of revealing and concealing. What happens is that the animals we bought tickets to see at the zoo hide from view inside their papier-mâché caves. Visitors accept this; in fact, we demand it. And why? Because that moment of surprise, of unexpected discovery of an animal that has dared emerge from the safety of its imitation habitat, replicates the very feeling that overcame our ancestors when encountering an animal in the wild. One could almost say that the average person goes to the zoo to not see animals, and for the chance to relive that lost feeling of freedom. To not see animals at the zoo creates a curious tension of expectation that seemingly makes us revert to the role of hunter-gatherer on the savanna.

Visitors to the zoo regularly encounter ruptures and jarring scenes that betray the fictional nature of the natural experience created there. The notion of the zoo relies on the theatrical staging of freedom. Any given scene, however, is embedded in the real world, which repeatedly breaks through the illusions it is trying to create. The visitors then realize they are living in a compensatory system, in which they are unable to describe what they see. A personal anecdote may help to illustrate this existential distance from animals that characterizes the zoo experience.

A sunny October afternoon in Munich. The Oktoberfest is over. FC Bayern Munich is already ahead in the soccer standings. The city exudes a self-satisfaction that stands in open defiance of autumn. The trees along the Isar River have changed to red, orange, ochre. Glasses clink in the beer gardens. My family is on a trip to the Hellabrunn Zoo, one of the few outings that both children and parents can happily agree upon, and that has therefore become a regular destination. We stop at the brown bear enclosure, which currently houses a mother bear and her cubs. The kids push their way through the crowd and press their noses against the thick safety glass. “Oohs” and “ahs” fill the air. Look how adorable those little bears are! A shadow suddenly appears—a group of ducks flies in and lands on the small pool that separates the bears from the visitors. A mother and three sweet little ducklings. It all happens very quickly: the mother bear doesn’t waste a moment. She plunges into the water, scatters the ducks with a swipe of her paw, and devours the small birds. Feathers are all that remain. Then she trots back to her cubs, which have been basking in the autumnal sun all the while. The visitors gape in horror. The first sobs emanate from the front row. Cries for Mommy. Mothers and fathers think frantically: What do I say to my kid? Honestly, what? Because that can’t possibly be the nature we set out to see this morning. I am one of those fathers who could not come up with a very good answer to that question.

It became clear to researchers at the Zoological Society of London that we no longer possess the language to adequately describe what we see in nature, because we have lost the sensory connection to them. The scientists are on a mission to photograph the Siberian tiger. What their cameras have captured, however, is a different natural display altogether: a golden eagle attacking a sika deer many times its size. It’s an occurrence very rarely seen. The truly spectacular photos circulate through the media. In the German daily newspaper Die Welt, one journalist pens the headline: “Rare, Brutal Natural Display Caught On Camera.” The article reads: “A golden eagle attacked an unsuspecting sika deer in southeastern Russia. It dug its talons into the animal until it died.” The word choice is revealing. The “brutality” of the event and the aggression—like the “unsuspecting” nature of the deer—are in the eye of the beholder judging the content of the footage. The same justification could be used to describe the “brutal” way in which the sika deer eats the bark off the “unsuspecting” birch. Et cetera, et cetera. The moral reflex embedded in our language shows our distance from what truly happens in nature. A tenor of sentimentality takes precedence, ascribing moral coordinates to essential natural processes and rendering the facts of nature literally indescribable.

Our lack of awareness about this distance can be attributed to the fact that we are now surrounded, on a daily basis, by humanized animals in hitherto unseen numbers. There have never been as many domestic pets on Earth as there are today. There are now over 160 million in the United States, well more than double the number in the 1970s. But these dogs, cats, and birds no longer play the role they once did. House pets used to serve humans. Today’s house pets are less animals that serve a distinct purpose, and far more integrated members of the family. They are part of their owners’ social networks. Pets have been elevated to morally qualified beings. This is a relatively new development in human history. In the early nineteenth century in France, dead dogs were simply discarded in the Seine. Things began to change only half a century later. Suddenly, Parisian high society began interring its pets in special pet cemeteries and adorning mantelpieces with stuffed dachshund heads in fond remembrance of the deceased. Dogs were outfitted with their own wardrobes, complete with boots, bathrobes, and bathing suits. Animals became social creatures, ersatz humans, as it were—and it is how they are treated to this day. We give them gifts, we give them human names, we dress them up and bury them like humans.

In reality, though, today’s house pets are little more than shadows of their ancestors. They are usually sexually isolated and confined to small spaces. They have little to no contact with other members of their species and are given artificial food to eat. In providing people with reminders of the natural world, they have become ossified, living pieces of furniture, props on the set of their owners’ life stories. House pets are hereby drawn into a cultural constellation that reduces them to mere toys, to home furnishings, or even to a symbol of a type of love many believe has ceased to exist in humans. The weary warrior of the civilized world finds a therapeutic, fetishistic release in the outcome of this transformation. Today’s house pets are no longer worthy counterparts in an existential exchange, but rather artifacts that need to find their place in our feel-good culture. It ultimately amounts to the same, whether they are living or stuffed and sitting on the couch, like so many dogs, cats, and horses that came before, and that were bound to be immortalized, their bodies manipulated into a favorite pose and stuffed with straw.

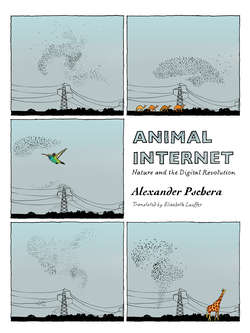

Bird-watching, zoos, house pets—all three forms of compensation merely give the impression of animal closeness by creating the cultural constellation onto which images of animals and snippets of nature scenes are projected. This is the most visible logic behind the compensation: nature is superseded by pictures of nature. The estrangement from animals is directly palpable in the untold number of animal images surrounding us. The more animals vanish, the more pictures of them appear. Humans try to hang on to the tangible reality slipping away by taking a picture of it. The desire to hang on to things signifies a fear of loss. Cell phone photography casts an unsettling light on our relationship with eternity. The people viewing a cathedral through the screen of their smartphone have lost sight of what this architecture represents. The faster we forget the animals, the more urgent our need to hang on to their image in photographs. This is an act of remembrance, a nod to the animal as man’s evolutionary partner.