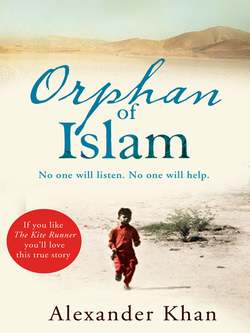

Читать книгу Orphan of Islam - Alexander Khan - Страница 12

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеIn Dad’s absence Rafiq appeared to make himself useful, at least in the first few months. He brought in some money – though never quite enough – as a taxi driver and would regularly do the shopping, arriving home with meat and vegetables for that evening’s tea. He even spent time talking to us children about our day and playing a little cricket or football with us in the backstreet. But his new-found parenting skills did not extend my way. He rarely spoke to me, and when he did, it was to interrogate me on what I was doing.

Abida seemed happy with her brother being around and chose to ignore his brutality on the night before Dad’s funeral. I think she was just pleased not to be alone; in her eyes Rafiq was providing for her and looking after the children. That was more than enough from a Pakistani man.

From an early age I’d worn mainly Western clothes, a mixture of hand-me-down or jumble-sale jeans, jumpers, shirts and cheap trainers thrown together with bits and pieces from traditional Muslim dress – salwar kameez tops and topi hats. Most kids my age were the same, and very few people thought it wrong or ‘un-Islamic’. We were all poor, and what we wore was a reflection of how much our parents had in their pockets. But Rafiq was different. Although he was personally happy to wear shirts, jeans and trainers while out working, he decided that I would be forbidden from wearing the gora, a term used to refer to white people. In this case he meant the English way of dressing. Even though I usually wore my jeans underneath my salwar kameez, they had to go, along with all my T-shirts. Rafiq gave no reason for this, except that he didn’t like seeing me in English clothes. I was allowed to keep my trainers only because they were black, and proper leather shoes were expensive.

Then there was the ongoing mosque issue. Rafiq pinned a calendar on the kitchen wall which gave the five different prayer times each day. There would be no more excuses; I would go to mosque five times a day, each and every day, and he would monitor my movements very closely.

After the beating I’d had from him I dared not disobey. It was a struggle getting up for dawn prayers, but I made sure I stuck to the timetable. Gradually I learned the ways of the mosque, like how to carry out the wudu ablutions, or purification rituals, before prayer. The Hawesmill mosque, like all mosques large or small, was fitted with a long metal trough with cold-water taps above it. Every time you go to pray, you have to wash yourself in a certain sequence – usually hands, mouth, nostrils, face, right and left arms, ears, neck and feet. After this you go into the prayer hall and line up in rows facing Mecca. There are prayers and readings from the Qur’an, plus religious or cultural speeches on being a good Muslim. The mosque has a strict hierarchy: elders at the front, their sons behind and boys at the back. Of course, all the prayers and readings from the Qur’an are in Arabic. Some Muslims pick this up very easily; I always struggled and although I was eventually able to repeat phrases parrot-fashion, it was almost impossible for me to understand what they meant. Having no one to guide me, I fell far behind in this respect.

All the time the beady eye of Rafiq was on me. I would carefully watch for the signal to kneel down or stand up again, knowing that he was waiting for me to slip up. Sometimes I did, and the result would be a blow to the back of the head as we walked home or, later on, a hammering in the confines of the bedroom. As he was doing it, he would mutter to himself. I heard him repeating the same words around the house during the day and realized he was reciting verses from the Qur’an. I assume he was justifying to himself the beatings he was handing out.

I remained as dutiful as I could, but sometimes it wasn’t easy. One night, just after I’d turned 11, I was coming home from evening prayers alone. To reach the mosque you had to go through a subway which went under the main road that cut Hawesmill in two. I’d never liked this tunnel. Rainwater, waste oil and urine mixed to form grim pools across its concrete floor and most of its orange lights had long since gone out. It was full of graffiti and a magnet for glue-sniffers from across the area. That night, as I picked my way carefully through the puddles in my cheap trainers, I noticed a couple of kids lurking near the exit.

It was too late to walk back. I went forward, my head held as high as possible. ‘I’m not scared, I’m not scared,’ I said to myself, hoping the mantra would protect me. But as I approached, I could see these kids were a year or two older than me – a lifetime when you’re that age.

‘Ey, look what’s coming,’ said one of them, ‘a little Paki! Awreet, curry breath, where are you going then?’

I tried not to look at the two white lads who were now standing in front of me, blocking the way out of this filthy place. I recognized one of them, a well-known troublemaker nicknamed Boo-Boo who lived in the mainly white estate beyond Hawesmill but ventured round our way whenever he dared.

‘Where’ve you been?’ he said aggressively, pushing me in the chest as he spoke.

‘I’ve just been to mosque … to church, you know? I’m going home now. Can I go past?’

‘No, you fucking can’t. Not until you say “Please, sir”.’

‘Look, I just want to get home,’ I said, trying not to shake. ‘My mum and dad are waiting for me. They’ll be mad if I’m late.’

As soon as the lie came out of my mouth I realized how truly alone I was. Strangely, it made me feel stronger. Whatever these two bullies were planning to do, it wouldn’t be anywhere near as bad as what was waiting for me at home.

‘Say “Please, sir”,’ Boo-Boo repeated.

‘Piss off,’ I replied and shoved past him as hard as I could.

I started to run, but he grabbed my coat sleeve and swung me round, punching me in the eye. His mate laughed and tried to swing a kick in my direction, but missed and overbalanced, falling to the ground. Boo-Boo hesitated for a second, thinking that I’d somehow tripped his mate, and I took advantage by pulling away and running off. They didn’t bother to chase me – in an Asian area they’d have stood out like two white sore thumbs, and Hawesmill certainly wasn’t short of lads who were handy with their fists.

I went into the house via the back door and ran straight upstairs to the bathroom, locking the door. An old sock was half-hanging out of the wash basket. I ran it under the tap and dabbed my swollen eye with it. When I was finished I opened the door, checked the coast was clear and went straight to bed.

That night I lay awake, thinking about the attack in the subway, Rafiq’s petty cruelties and his nit-picking attitude. I wondered why the family wouldn’t just let me go home to Mum. I thought about this a lot. If they couldn’t stand me, surely it would’ve been better for them to hand Jasmine and me back? That was, if Mum was still around, of course, or even still alive. I had no idea about either possibility. Her name was still occasionally mentioned when Abida or Rafiq or Fatima thought I wasn’t listening, accompanied by tutting and shaking of the head.

There was also still the odd time that a knock at the door remained unanswered. Once, as I was coming downstairs, there was a knock on the door and I was the nearest person to it. I had a feeling that behind it would be a woman with long dark hair and a big smile. Before anyone else could get to it, I flung it open. I was right. The woman on the doorstep had long dark hair and a big smile – but she was Asian. Just another ‘aunty’ from up the street, calling round for a cup of tea and a chat.

The next day I was woken up as usual by Rafiq roughly pushing me and demanding I get up for mosque. I complied, knowing that Boo-Boo and his mate would still be in bed. But as the day went on I became more fearful of meeting the pair again. When it came time for evening prayers I decided to appeal to Rafiq’s better nature.

‘You what, bastarrd?’ he said, as he slouched in Dad’s old seat, legs splayed out. ‘Tell me again – you don’t want to go to mosque tonight?’

‘You don’t understand,’ I pleaded. ‘There were these two lads, white lads. They beat us up under the subway. Look at my eye!’

He grabbed me by the arm and pulled me towards him, poking my painful and swollen eyelid.

‘That’s nothing compared to what I’ll give you if you don’t go!’

‘Please, Uncle Rafiq, I’m scared. Will you come with me then?’

‘What are you scared of?’ he snapped. ‘You said they were white boys. So tell them you’re a white boy too, kuffar!’

With that, he grabbed me and pulled me out of the living room. ‘Here we go again,’ I thought. But he didn’t go upstairs. Instead he pushed me down the hallway, through the kitchen and into the backyard. In one corner there was an outside toilet, left intact from Victorian days. It still worked, and was occasionally used when the bathroom was occupied. I hated going in there. It was dark, smelly and full of spiders. Rafiq knew I didn’t like it, and without further ado he pushed me in and locked the door from the outside.