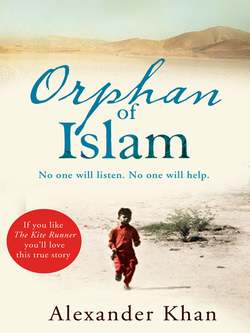

Читать книгу Orphan of Islam - Alexander Khan - Страница 8

Chapter One

ОглавлениеI see a face, a white face, but I don’t recall any features other than dark eyes and a smile. What I remember most is her long dark hair. As she bends down, it tickles the sides of my cheeks and I laugh. She laughs too, then the sun comes out and streams through the thin curtains of the living room. She turns away and is gone. This is the only memory of my mum I have from childhood.

I’ve no idea what she was like as a mother during those brief first few years. I can’t recall the stories she told, the food she cooked, the games she played or even the sound of her voice. There is no scent in this world that evokes her smell, no object or place that brings back those precious moments in time. Dark hair and a white face are all I have, and while that hasn’t been much, it has been enough to hang on to in my worst moments. I always knew she was out there somewhere, even when she’d apparently vanished from the face of the Earth. All I wanted was her to come back and take us home.

What I know about Margaret Firth is what I’ve pieced together over the years and what I’ve learned more recently. She was born near Manchester, the youngest of three sisters living in a house of poverty and pain. Her parents had little time or regard for her. Although she looked up to her sisters, it wasn’t the easiest of relationships. When her elder siblings moved out and made lives for themselves she would go to live with them from time to time, returning to her parents’ home when they’d had enough of her. It was a lonely life, back and forth between people who didn’t really want her. Her parents worked in the textile industry. Margaret would eventually do the same, getting a job in a local mill as soon as she left school.

My father, Ahmed Khan, was born in the village of Tajak, in the Attock district of north-west Pakistan. It is a rural and deeply religious area not far from the North-West Frontier and the border with Afghanistan. Ahmed was the eldest of five siblings: three brothers and two sisters. For the first 30 or so years of his life he lived pretty much how people have lived in this area, close to the Indus river, for many years. The men rise before dawn and go to the mosque for prayers. They return home to walled compounds containing several houses occupied by members of the extended family. Their wives are already up and have prayed in their living rooms on a mat facing Mecca. Then it is into the kitchen to cook curry and chapatis. The food is placed in a small clay pot with a lid on and given to the men as they head out for a day working in the harat, or field. Each family has its own plot of land, irrigated by a large well and including a small brick hut containing tools. Many men spend their entire lives in this routine, their faces etched with deep lines by the sun. Others become drivers or co-drivers of the trucks and buses that travel ceaselessly across Pakistan and beyond. Some turn into mechanics and set up their own garages; others open grocers’ shops. In these rural villages the women just stay at home, raise children and keep house. They are not allowed to do much else.

But even in these insular communities there are men who seek something else. My father was one of them. His eldest sister, Fatima, had travelled to England with her husband, Dilawar, and set up a shop in a mill town in Lancashire. Letters came to Ahmed telling of a wonderful island where the sea was close by and earnings were three, four and five times the amount they were in the village. Fatima revelled in her status as an emigrant adventurer and encouraged her older brother to follow suit.

In the late 1960s the only way for a poor Pakistani to travel to England was by road. It was a 25-day journey across difficult terrain and through inhospitable countries. Dad made an attempt but was delayed in Karachi and his money ran out. It didn’t put him off; he went home, saved up and within a year tried again. This time he succeeded and, after spending time earning money on construction projects in Germany, arrived in England just before the end of the 1960s, with many other Pakistani, Indian and Caribbean immigrants.

Dad went straight up to Lancashire and to the Hawesmill area of the town his sister was living in. Hawesmill was built in the late nineteenth century to house large numbers of mill workers cheaply. Streets lined with stone-built terrace houses stretched for hundreds of yards up steep, windswept hills, forming a tightly-knit enclave that seemed forbidding to outsiders. By the time Dad arrived, many of its white inhabitants had gone for good. Cotton was no longer a major industry in Lancashire – although some mills were still working – and Hawesmill’s rundown old housing had almost served its purpose. But not quite, for a new set of people had moved in, and were finding the natural insularity of the place to their liking. Bengalis, Punjabis, Sindhis and Pathans were making Hawesmill their own, laying down roots and traditions founded in far-off villages. To the rest of the town, they were just ‘them Pakis’.

My father was a Pathan, one of a light-skinned and tall race of people who originate from Afghanistan and north-west Pakistan and speak Pashto. They were part of the Persian Empire and throughout history were known to be fierce warriors, defeating everyone who dared invade their lands, from Alexander the Great to the Soviet Union. As we know, they are still fighting today and are a strict, unyielding and deeply religious people. That said, they are also warm and if you befriend a Pathan, it’s for life.

Fatima was keen to help out her brother and persuaded her husband that he should have a job in his shop. Dad worked there for a while, but the wages were low and it was a matter of pride that he sent money back to the family in Tajak. He left the shop and found a job in a mill in Bolton that took on immigrants prepared to work for lower wages than white people.

He lived in a terrace house with four other men, all Pathans from the same area, and they hot-bedded: when one was on a night shift another would sleep in the bed, then vacate it to go to work when the night worker came home. If there was a time when they were all together, they would sit in the front room of the house, smoke cigarettes and play cards and talk about work and how they missed Pakistan. They would only go home, they declared, once they’d made enough money to build a house in their village. In winter they would pull worn-out second-hand coats over their traditional salwar kameez clothing when they went outdoors and learn not to moan too much about the wind and rain coming in off the bleak moors. Lancashire wasn’t home, and would never be, but when they talked and listened to Pathan music, home didn’t seem so far away. ‘Only a few more years,’ they’d promise themselves before heading off to the mosque – a couple of terrace houses knocked into one. Men from all over Hawesmill would squeeze into it five times a day. This was the reality of Dad’s adventure in England, day after day after day.

No wonder, then, that his curiosity was aroused when a young Englishwoman caught his eye during his shift at the mill. He didn’t know any white people and he couldn’t speak much English. He saw no reason to mix; from what he’d heard, whites didn’t like Pakistanis ‘coming in and taking all the jobs’. But this woman seemed different. She smiled at him, and it was genuine. Shyly he looked away, then back again. She was still smiling.

‘Hiya,’ she said, ‘what’s your name?’

He shrugged, not understanding. But a Bengali friend working on the same shift could speak half-decent English and caught the question.

‘Hey,’ he said to Dad, ‘the girl’s asking your name. Aren’t you going to tell her? She’s a pretty one. Go on, tell her …’

Dad smiled, but said nothing. Farouk leaned round the spinning loom and shouted to the girl, ‘It’s Ahmed … Yeah, Ahmed. He likes you. Talk to him.’

Margaret Firth, 18, lonely and lacking confidence, liked her Asian co-workers. They seemed quiet and dignified, never complaining like the local Bolton lads or drinking and messing about. She appreciated how respectful they were when they spoke to her. And there was something she really liked about Ahmed, even if he couldn’t hold much of a conversation.

Dad was a village boy, but he wasn’t daft. He’d made it to England, found work and was sending money home. He missed Pakistan, but he certainly didn’t want to go back. Not yet. What better way to stay than to marry an Englishwoman? It would give him residency and maybe take him out of Hawesmill altogether. The idea of marrying someone from a non-Muslim background would horrify his sister and the Pathan communities in both Hawesmill and Tajak, but no matter. He would bring her into Islam, and Fatima would teach her the ways of Pakistani women. It would be fine.

Now, I don’t really know if this was the case or not. Perhaps Dad got together with Mum out of love. He certainly liked her enough to introduce her to the family in Hawesmill, braving the stares and whispers that she must have attracted. Mum seemed happy to go along with whatever he wanted. For the first time in her life she’d found someone who treated her with kindness and respect. She was young and impressionable. The language, the clothing, the customs and the cooking all baffled her at first, but when Dad asked her to live with him in a rented terrace house she agreed immediately. They had a formal nika, or engagement ceremony, performed by the local imam. She dressed the way Dad wanted and learned to cook the food he liked. He tried to improve his English. Maybe they would be alright.

Dad’s sister didn’t think so. Fatima was against the relationship from the start and was horrified when they set up home together. It was haraam, strictly forbidden in Islamic law, and a source of dishonour. Fatima was a pioneer, the first of her family to live in England. Her word was law. Ahmed was bringing shame on her and Dilawar around Hawesmill. Again and again she begged him to leave the Englishwoman. Dad was having none of it. Mum’s parents didn’t want anything to do with her, so they eloped to Scotland, where there were jobs waiting for them in a textile mill in Perth, and finally married up there.

I was born on 22 February 1975 and named Mohammed Abdul Khan. My sister, Jasmine, was born in March the following year. Dad was now the father of two British-born children and was entitled to stay in the country for as long as he liked.

What happened next is unclear. There are stories of Dad starting to get a taste for whisky – also completely haraam under Islamic law. Never having drunk alcohol in his life, he became aggressive. I’ve been told he started hitting Mum while drunk. Perhaps he found being married to a Westerner and fathering two children with her much harder than he had expected. Maybe he missed Hawesmill or even Tajak.

What I do know is that within a relatively short space of time, the four of us were back in the north-west of England. Mum and Dad rented a house in Bury, picking up jobs in what remained of the rapidly declining textile industry. Dad seemed pleased to be closer to his family again, but his happiness wasn’t shared by Mum. Fatima was now openly hostile towards her, shunning her when we went to visit and speaking in Pashto to confuse her.

Dad was the source of more grief. He’d stopped drinking, but was now disappearing from the house for days and even weeks on end. ‘Family business at home,’ Mum was told. In this case, ‘home’ meant Pakistan. Without explanation or apology, Dad would just pack a suitcase and go. Mum would be left with two children in a damp, rented terrace house, with no idea when he would come back.

One morning in desperation she put us in the pram, got the bus to Hawesmill and walked up the steep street to Fatima’s house, determined to find out what her husband was up to.

‘Is he here?’ she demanded, as Fatima opened the door. ‘Or is he back in Pakistan? I’ve got two little kids here who miss their dad. I know you don’t like me. But I’ve a right to know what’s going on.’

Fatima paused. She had no time for this kuffar, this unbeliever, who had brought shame on her. But she felt that she was entitled to an explanation. Maybe if she heard the truth, she would disappear very quickly. She invited Mum to come in and sit down.

‘You should hear this from Ahmed, not me,’ said Fatima. ‘But since he’s not here I may as well tell you – the reason he goes to Pakistan all the time is because of his family.’

‘I know that,’ said Mum. ‘But if he’s so desperate to see his mum and dad, or his brothers, sisters, aunties, cousins, whoever, then why doesn’t he just bring them over here for a visit?’

Fatima smiled. The poor woman was clueless.

‘Not that sort of family,’ she said. ‘Ahmed has a wife in Tajak. He married her before he married you. Oh, they’ve got a few children too.’

I wonder what Mum thought as she wandered in a daze back to the bus station that day, the hems of her badly fitting salwar kameez trousers trailing through puddle-strewn cobbled streets, with two scruffy mixed-race kids crying in the pram. Meanwhile, somewhere hot, somewhere she’d never been invited for now obvious reasons, Dad was enjoying the fruits of his labours with the family he’d kept secret from her.

I was too young to remember the row that took place when Dad finally got home. It must have been one hell of a ding-dong. I imagine Mum screwing her Asian clothes up into a ball and throwing them at him, then telling him to cook his own bloody lentil dhal. It sounds almost comic, like a scene from East Is East, but it must have been awful. However it was conducted and whatever was said, the upshot was that Dad moved out of our house and into Fatima’s, leaving Mum with custody of the pair of us.

Now I believe Fatima acted maliciously by telling Mum the truth about Dad. She wanted to split them up. But in a way Mum had what she wanted – two beautiful children to care for and love as she had never been loved. She didn’t have to fit in with foreign customs anymore or cook funny food. She had a roof over her head and a job. There were people saying, ‘Told you so,’ but she didn’t care. I’d like to think that my first memory of her happened around this point: her smiling face turned towards me and the sun coming out.

‘Mohammed, oh my Mohammed …’ Do I remember her whispering that as she cuddled me protectively to her? Perhaps she did. At any rate, I’d like to think she was happy.

Dad still wanted to see us and would call round at weekends. Mum was still angry with him, but didn’t stop him from visiting. I guess he wouldn’t have taken us much further than the local park or the ice-cream parlour, and up to Hawesmill to see the family. Whether they wanted to see us would have been another matter, but knowing Dad he would’ve made sure that the family connections so important to Muslims were maintained, even if they included the children of an unbeliever.

One Saturday in the early part of 1978, just a few months after Dad and Mum had split up, he called for us as usual. He made sure we were dressed in our best clothes and also had a change of outfit. He explained to Mum that there was a family gathering in Hawesmill because a relative had flown in from Pakistan. We needed a change of clothes, he said, because we’d end up playing in the backyard and would get filthy. Mum packed us a little bag each, kissed us both on the head and saw us to the door. I guess we turned and waved to her as we climbed into the back of the battered old Datsun Dad always borrowed to pick us up. She shut the door, happy that she had a few hours to herself before we returned, tired out, after a long afternoon’s playing with the local kids in Hawesmill.

In the 1970s only lucky little English kids travelled on aeroplanes. Normally a family like ours would’ve been completely out of the international air travel league, but strong ties to Pakistan meant that money was somehow found to make the trip ‘back home’ and see relatives longing to hear stories about the land of opportunity that was giving such a warm welcome to its former ‘colonials’. I expect there was a whip-round in the streets of Hawesmill in the weeks before Dad came to pick us up from Mum’s. Whatever work Dad was doing at the time – shifts in the mill, plus a bit of labouring on the side – wouldn’t have paid for three airline tickets to Islamabad. That said, two of those tickets were one-way only, so maybe there was a discount. I don’t know – I’d just turned three and Jasmine was almost two. Babies, really – and far too young to be removed from their mother without explanation.

From what I can gather, the police were involved. I’d like to think that Mum banged on every door in Hawesmill for answers. She certainly did later on, until it became clear that she wasn’t going to get a straight answer out of anyone up there. But what were the police’s chances of making an arrest? An Asian man takes his mixed-race kids to Pakistan for a holiday and forgets to tell his estranged wife, a white woman who tried to fit in with the funny foreigners but wasn’t welcome – sounds like an open-and-shut case. Perhaps the police thought she had it coming to her, or maybe they did try hard to find us. But the trail would’ve gone cold as soon as we arrived in Islamabad, and I don’t think the law could’ve expected much help in Hawesmill.

We were taken to Tajak for a ‘holiday’ and put in the care of various ‘aunties’, some related, some not. Dad stayed for a while, a week or two perhaps, then went back to England. The need to earn money must have been overwhelming, because of course he had two families to support, so staying in Pakistan for any length of time wasn’t an option.

Meanwhile Mum made repeated attempts to track us down, without success. She must have been heartbroken, trailing those windswept terrace streets for her two missing children and begging Fatima for news of our whereabouts. What did they tell her – if anything? Many years later, I was told she had been informed by Dad’s family that we’d been killed in a car crash while on holiday in Pakistan, and that we’d been buried there. What a terrible thing to say to a mother, especially when it was a barefaced lie. Mum, poor and isolated from her own friends and family, could do nothing to disprove it. Luckily, she never believed it.

I can’t recall if I met my step-family at this time. It’s probable, given that Tajak is a small place, but being so young, I don’t have any memory of them. What I do remember is the day I was circumcised. Although it isn’t mentioned in the Qu’ran, circumcision (tahara) is a long-established ritual in Islam. It is to do with cleanliness and purification, particularly before prayer, and there was no reason why I would be exempted. Unfortunately for me, Mum had opposed this after my birth and Dad had no choice but to postpone it. Now she wasn’t around he could do what he liked, and one of his first jobs in Tajak was to find somebody suitably qualified to do it.

It goes without saying there was no anaesthetic. Dad would’ve rounded up the village imam, who also served as the village doctor, and a few of the elders, to oversee proceedings. I don’t recall their solemn bearded faces leaning over me as I lay on a scruffy bit of carpet in the village mosque, but I do remember the searing pain as the razor-sharp butcher’s knife cut through my little foreskin and my blood staining the carpet a deep red. Iodine must’ve been applied very quickly, as I remember looking down and seeing my genitals covered all over with a substance the colour of saffron. For days afterwards I suffered burning agony when I tried to pee. If I called out for my mummy at any time during those hazy, fractured few years, it would have been then.

My only other memory from this period is when I tried to shoot the moon. I’d found an old pellet gun in the house where we were staying and had been encouraged to take it outside and learn to use it. Having a gun in Pakistan is no big deal and boys handle weapons from an early age. Seeing an old shotgun propped against the interior wall of a house or an AK47 left in the corner of a mosque while its owner says his prayers isn’t uncommon. So the uncles of the family must’ve been delighted when I picked up the gun and lugged it outside. The moon was an obvious target. I’d never seen such clear skies in my short life; the sheer number and brilliance of the stars in the night sky was mesmerizing, and the moon hung in between them like a gigantic waxy-yellow fruit. I heaved the rifle to my shoulder, assisted by Jasmine, and took careless aim at the sky. No one had told me about recoil, so when I dropped it immediately after it went it off, the butt landed right on Jasmine’s foot, leaving her with a deep cut and a permanent scar.

We didn’t go to school during our time in Pakistan. Our family in England spoke Pashto among themselves, so it’s not as if we knew nothing of the language and couldn’t have managed to some extent in school. But I imagine the Pakistani relatives thought there was little point in sending us; we probably seemed happy enough, playing in the dust beneath the brick and mud walls of the houses or watching the farmers slowly gather in their crops under the vast and cloudless sky. The days were endless and dangers were few. My Pashto was certainly getting better, and after a year or so I could communicate with my cousins. If Dad hadn’t needed to earn money in England, maybe this is where my story would’ve ended. I’d have remained in Pakistan all my life, tending the fields or driving trucks or fixing cars or keeping a shop. In time the memories of Mum would’ve faded, and although I might never have fitted in – the gossip about the boy with the kuffar for a mother was unlikely to disappear – I’d have probably had an arranged marriage with a cousin and spawned a few kids. The opportunities to do anything other than conform would’ve been extremely limited. However, it might have been a much happier existence than the one that was waiting for me.

After spending three years in Pakistan, not knowing who we were or if we really belonged to anyone, we were taken back to England. That’s when my troubles really began.