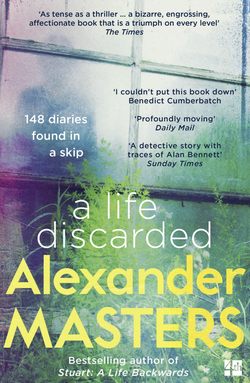

Читать книгу A Life Discarded: 148 Diaries Found in a Skip - Alexander Masters, Alexander Masters - Страница 12

5 The Torso box

ОглавлениеGot two obsessions – that I’m going to be an author; and that I’m going to choke.

Aged twenty-one

In 2005, I left Cambridge and rented a shooting lodge in Suffolk, and the diaries became a makeshift boot stand. In 2006, my girlfriend Flora and I went to London to house-sit for a pianist. The torso-sized printer box became a cocktail table; the box the size of a thigh propped up a chair; the Ribena crate, too wonky to be of any use, got kicked under the Steinway.

In 2007, Dido was told she had neuroendocrine cancer of the pancreas. In 2009, that it had spread.

I had known Dido for twenty-five years. When I first met her my father was dying – she saw me through that; I was twenty-one and idiotic. She was twelve years older. She grew me up, taught me how to think, how to write, how to be.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine cancer is the same disease that killed Steve Jobs, and is why he was able to develop the iPad and the iPhone. If he’d had ordinary pancreatic cancer (as almost all newspapers insisted on giving him at the time) he’d have been dead before the MacBook. Neuroendocrine tumours can be very slow-growing. Some people live the rest of their natural life with them, as long as they do not spread.

Dido’s tumour had seeded over her liver. Its spores had crowded into her blood.

The consultant at Dido’s local hospital was contemptible: bullying and scary. I arranged for Dido’s case to be moved to the Royal Free in London, a European Centre of Excellence for neuroendocrine cancer. There was a scan due in six weeks’ time; I had to be on the phone every morning to reduce that to ten days. The NHS is a wonderful organisation as long as you learn how to kick it. There were anti-cancer diets to be researched, exercise programmes to be uncovered, high-absorption liposomal curcumin to be ordered in from California at $95 a 100ml bottle (produced by a man who, I subsequently discovered, was being pursued on a manslaughter charge), electrically-operated pomegranate squeezers to be shipped from Istanbul, a remarkable peer-reviewed but forgotten therapeutic from Sweden to be investigated. In fact, why are we still talking? I had to get on …

During the five years Flora and I stayed in the London house, I’d occasionally catch sight of the boxes and remember their contents with dislike: that terrible face; those tiny scuttling letters; ‘I’s sense of destiny and devotion to an unknown, perhaps unknowable project of vital human importance followed by the catastrophic failure of all his plans. Despite the glistening orange and shocking pea-green covers of some of the books, I thought of them as pallid objects. I had the same feeling towards the diaries in these boxes as I do towards the ghosts in an M.R. James story: thrilling, but forces of absence; not so much evil as empty of good. They marked a time when Dido was well. They emphasised that she might be dying. They were hateful.

Occasionally, I’d creep under the Steinway and peer inside the Ribena crate. But I didn’t study the books. I reversed back out between the legs of the piano with the slightly appalled sensation that I was escaping quicksand.

Flora and I moved again in 2011, to Great Snoring in Norfolk, by which time I had forgotten about the diaries. They were just three more boxes among the thousand or so that I drag about like Marley’s chain every time I change landlords. I shoved them into the back of the van with the rest, yanked them out among the chickens and runner ducks at the other end and dropped them into a storeroom.

At which point the Ribena box burst open and twenty-seven diaries spilled out.

One of them featured a bloodbath.

The Collins ‘Three Day Royal Diary’ is greeny-blue, not much bigger than a jacket potato and caved in halfway up the spine, as if it has been crushed by a spasmodic grip. I tested it, waving it around the chicken yard in Great Snoring with various holds of my own. Only a left hand could make this type of depression. It was a gesture I imagined an outdoor preacher would use as he clutched the Gospels and harangued cowboys.

An inside page printed with useful information calls New Year’s Day ‘the Circumcision’.

Once again, the diarist’s handwriting races into the book many sides before the official diary section starts:

November 19th, Saturday

Spent most of today painting. Perhaps it is the best I’ve

ever done, more like Van Gogh than anything else.

and 126 pages and four weeks later shoots out from the bottom of the last possible page, with the words ‘watched her go with foreboding …’

In between, ‘I’ describes a stabbing.

Then,

to my horror, – a sudden burst

of blood rushed from my body

Ran about, & outside the house

calling for Nizzy desperately.

never lost so much [blood] so suddenly before in my life,

felt terribly afraid.

Who has stabbed him? Why? Who is Nizzy? ‘I’ doesn’t say. Where is he outside? Bleeding on the road? In the garden? I picture him leaping about a rockery as he clutches at his wound. What time is it? It might be first thing in the morning, because ‘I’ reports that he’s in his pyjamas. But then he’s a painter, so it could be any time of day.

Nothing about the methodical, evenly-spaced way ‘I’ forms his letters changes during this dramatic episode. If anything, a calm comes over the text. ‘I’ calculates that he will need a ‘blood transfusion’ and thoughtfully returns to the house to call his doctor so the hospital will be prepared for his arrival and have the machinery set up. But the sheet of telephone numbers beside the phone is missing – an absence that’s as good as finding the telephone wires have been cut. Weeping ‘with the added frustration’, ‘I’ scrabbles around for the phone list.

Then, abruptly, the squall ends.

The bleeding stops. Nizzy comes home and turns out to be his mother. ‘Crying in that uncontrollable way I sometimes have’, he tells her about the blood. Nizzy says he ‘is fussing unnecessarily’.

Our mystery diarist hasn’t been stabbed, slashed his wrists or fallen out of a window into a greenhouse. He’s suffering ‘because of my sex’.

The poor man’s got the curse.

He’s a woman.