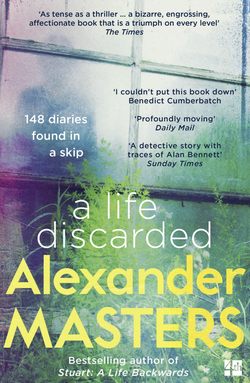

Читать книгу A Life Discarded: 148 Diaries Found in a Skip - Alexander Masters, Alexander Masters - Страница 17

10 Ancestors

ОглавлениеMust tell E about how distinguished my family is.

Aged nineteen

The first thing every biographer needs when he’s trying to make sense of 148 notebooks is another notebook.

How do you begin to catalogue five million words of anonymous writing? In the sticky-bits section of W.H. Smith I picked up Post-it notes. Among the computer software packages, I selected a docket for voice-recognition software. It would take only a few years to read in the entire 15,000 pages. In the hardware department, I changed my mind again. Delighted by the £40 photocopiers, I hoisted one to the checkout; I would do my editing on a duplicate of the books – now I’d have thirty thousand pages. Everything I thought of seemed to involve either damaging the books, or producing so much preparatory work that I’d be dead before I began.

In the end I bought a packet of highlighter pens.

Back at home, I categorised information into five types, one to each radioactive tint of my new highlighters: blue, for physical descriptions:

Mother says I look like a sick ostrich.

Orange, for biographical information:

I have some sort of inkling that I might have been at the Coliseum in Rome, in a former life.

Pink, for names: Nizzy; Sweet Swoo’ Boodies; an art student called Wolffsky who never – ‘gnash!’ – becomes her lover; his rival, who goes by the name of only ‘E’; Boots; Humfee; sisters Noon, Woill and Kate, aka ‘that perfectly repulsive child’ …

Green highlighter was for examples of particularly good writing and quotable text:

Went out to the library & Backs, sketched St John’s bridge on a Cambridge evening. Homesick for Cambridge even whilst I’m still in it – the leaf-lit path in John’s – a pattern of shade & sun all down the long wide walk, like a fantasy; walked with my head in green leaves & my feet on gold.

My diary-writing rather like a form of prayer – do not pray, but of that temperament – confide on paper, & get strength from it, it purifies my soul. It is auto-suggestion, like prayer.

If I die, I will leave countless of these little diaries, full of heartbreak.

And yellow, for anecdotes:

March, 1959: Archbishop Ramsey gets into her bed.

March, 1960: The second knife attack.

July, 1961: Feeding employer’s best cut of lamb to the dog.

I imagined this multicoloured approach would be like extracting a body from an Irish bog, using neon highlighter instead of a shovel. I pictured the books laid out in the British Museum, a hundred years from now: Forensic Biography Began Here! Author Excavated Subject Using Staedtler Pens!

Behind, stretching into the penumbra would be the annotated diaries, glowing like fuel rods …

Picking out a small memo book, dated 1961, I made immediate progress with blue (physical description) and green (quotable):

A note on my hair – it is glorious, tremendously thick, shining in rich goldy & reddy-brown & dark lights – prodigality of Nature for my youth, it won’t last forever. ‘Beauty that must die.’

And on a sheet of blank paper, I began a portrait:

which looks like the silhouette of an East End boxer glowering out of a wig. There is no further physical description in the 120 pages of that book. She remains a hairpiece for four years.

Mr Hely this afternoon – in many ways, I enjoy these visits to the dentist! Enjoy chatting with this kind, feeling man. The treatment was uncomfortable – injections in the vein at the back of the jaw [but] I am so eager to give & receive love, like a desperate little girl, that I got something out of this social contact. Liked his body pressed close to mine, as he sat, & working with his hands on my mouth; the beauty, the tenderness of a man’s arms and hands. And feel he likes me, feels the attraction of a girl, with a lot of hair.

In the next book, dated 1963, she is in London at the Camberwell College of Art, working as an artists’ model:

One girl had done a nice sketch of me, & more true to me than a camera. A delicate face, interesting up-slant eyebrows …

The sketch isn’t included in the diary, and it’s impossible to draw delicacy in a face without further information about the nose, so I added just the eyebrows:

‘… and light glasses …’ continues the entry:

‘… and the very long bones in my arms, giving me a touch of angularity’:

The diary after that, she’s in a locker room, ‘heart beating fast with expectation’, hoping to wrap those bony arms around the etching master, a man called ‘J’ with ‘gorgeous eyes, the eyes of genius’ (yellow highlighter: anecdote) – at least, she thinks that’s what he’s got, because ‘am too short sighted to see him well’.

While waiting for him to lunge at her, she hands him a love letter.

But it turns out ‘J’ doesn’t know her first name.

The situation is disintegrating rapidly, so as he accepts the envelope he makes a stab in the dark:

‘Mary?’ he mutters.

Her name is not Mary.

But she doesn’t tell us what her name is.

After a few days I abandoned the highlighter approach. It made the pages look like a municipal flowerbed.

In these early books one name is particularly important: Whiters. He is a figure of yearning, despite his butlerish moniker. ‘Just adore Whiters so.’ He whips Not-Mary into poetry. She loves Whiters ‘like a passion in my blood’. With him, romance ‘fills my soul’. But he is also a murky figure. There is no physical description of him. He is clearly manly, yet Not-Mary gives us no sense of his body. To me ‘Whiters’ suggests somebody in late middle age, barrel-chested, with elegant legs, wearing a dry-cleaned, off-white linen suit. He is a little like my father. The fact that she refers to him by his full nickname, ‘Whiters’, rather than just ‘W’, also suggests to me that he is a type of father figure, remote and comfortingly superior, and married. She has known him since she was a very small child.

All the same, only when she is with Whiters does Not-Mary feel fully alive, intense, thrilled to her essence by the thought of what life has to offer her – a life that will be ‘dominated’ by Art, Beauty and Music. Whiters embodies this mood of radiant potential negatively. He is not an artist. He does not play the piano with thin hands, as does her main boyfriend, ‘E’. Whiters’ value is that he is a figure of relaxation: he is ‘so lovely, so soothing’. Whiters is ‘understanding, restful’; Whiters is ‘a solace to my irritable, jittery nerves’. In Whiters’ presence, the outside world and all that is fretful drop away, and Not-Mary expands into artistry. E (boyfriend number one) is positively artistic, but E is difficult. Whiters is ‘joyous’.

Not-Mary appears to be in her early twenties at this period. She is living in bedsits and has no money and, when not thinking about Whiters or E, she is thinking from breakfast to supper about other men.

Think I am rather a ‘sex fiend’ just lately – men excite me! Would love to lie in the arms of a man (but with clothes on, think the idea of nudity rather disgusting).

As I was putting one of these early diaries back into the Ribena box, a sheet of blue writing paper dropped onto my duvet. It was small and carefully folded in half, and had created a light indentation in the pages on either side of its hiding place. There was no handwriting. It was blank on both sides. But it was a message from Whiters, all the same: in the left-hand corner at the top, embossed in black in an old-fashioned, self-conscious font, were three lines of an address:

Whitefield

Hinton Way

Great Shelford

‘Whiters’ is Whitefield: not a lover, but a house.

‘No! Not there, love!’

‘Take a plastic bag to sit on if you go in there, darling!’

‘That’s the … B … F … I.’

‘The British Film Institute.’

‘Booths For you know what, more like! Two residents’ permits, did you say? No, you can’t have that …’

I was at the parking permit desk on the top floor of the Cambridge Public Library, trying to find my way to the local history section.

‘Last week,’ whispered the woman behind the nearest counter, ‘when the staff went in to get them out, the man refused to stop! The door you want, love, is over there, on the left.’

The Cambridge Public Library is busier and more fun than the University Library, half a mile away. It is open to everyone and satisfies every need, except privacy. School children mumble intimately down their mobile phones. Foreign students make pingy noises with electronic products. Mothers repack their shopping while their children shoot each other among the DVDs. There is only one place where silence reigns: the Cambridgeshire Collection, set apart from the bustle in a bright room behind a bank-vault door. The tables inside are broad and glossy. There are display cabinets exhibiting pamphlets by famous Cantabrigians who have nothing to do with the university, and a collection of clippings about the 1956 flood. There are also three sets of metal shelves containing small, decaying telephone directories. Otherwise, few books and fewer readers. The place has the feel of a doctor’s waiting room, when you’ve arrived on the wrong day.

‘How can I help?’ said a sharp voice from behind a computer screen, which turned into a woman’s face as I entered. The computer made a gentle whirr. There was a pleasant hum of strip lighting, and from somewhere a suggestion of an open window letting in the summer air.

I handed across my sheet of blue letter paper with the Whitefield address.

‘Great Shelford, yes, mmmm … Hinton Way,’ said the woman’s face. A tall body appeared under it, and walked with pronounced steps across the carpet tiles to the telephone directories, reached over the top of the books and tapped at one from behind to nudge it out. ‘And who lived at this address?’

‘I don’t know. Well, I call her Not-Mary, because she’s not called Mary. I don’t want to know her name, in fact. If you find her name, would you mind covering it up?’

The librarian stopped tapping, considered me thoughtfully and without surprise, and moved six books to the right.

‘When did she live there? Or is that another thing you don’t want to know?’

‘I don’t know that she did live there. Maybe she just stole letter paper from there. That would explain why she kept this blank sheet – a sort of trophy. The writer doesn’t give her name or home address. She’s just “I”, who lives … “I”, who might be anybody,’ I added portentously.

The librarian stepped around and behind me, because I was the only real obstacle between her and the facts, and reached down for a third book, riffled the pages, nodded at one in particular, and hurried away.

‘The diary I found the paper in was dated 1962,’ I called after her.

The Readers’ Room of the Cambridgeshire Collection is not where the research material is kept. The proper archive is behind the librarian’s desk, past a set of swing doors in the Cavern of Documents.

Twenty minutes later, the librarian returned carrying a thick folder. She let it slide down her forearm and wallop onto my table. In her other hand she held a thin booklet, which she handed to me.

‘That’s what you need to read first to solve your mystery. It begins four hundred million years ago.’

It was entitled Whitefield, Hinton Way, Great Shelford: An Archaeological Evaluation.

Four hundred million years ago, Britain was covered by a shallow ocean. The Peak District was an archipelago of islands. Snowdonia had the climate of Hawaii. Everywhere, this mass of water was filled with ammonites the size of small cars. Then the volcanic arrival of Iceland pushed Scotland up in the air; Africa crashed into the Mediterranean and Britain became dry and rippled. Whitefield got its name because it sits on a ripple that is made of old shellfish. At the back of the house is a disused quarry, where the clunch – a poor-quality limestone – was dug out to supply building materials for the field workers’ cottages in nearby Shelford.

Whitefield House is one of the most expensive properties in Cambridge.

It’s so exclusive, it’s invisible. The chunky Cambridgeshire Collection folder contains a sales brochure from 1974 which reveals that the property has an indoor swimming pool, a conservatory, a ‘games room’, an entrance lobby, a clunky attempt at a baronial staircase, a library, eight bedrooms, and is decorated throughout in pop-star green and silver. The drive leading up to the house runs for a quarter of a mile through an avenue of limes. The building sits on top of a hill, in the middle of twenty-four acres of woodland, just to the south of Cambridge. If it weren’t blinded by the trees that surround it, it would have a stunning view. Look out of the train as you pull away from Shelford station to begin the final surge into Cambridge and you can briefly spot the delicious place, disappearing behind you: it’s about halfway up the right-hand window, an uneven canopy of oaks and cigar-shaped specimen trees that push above the leaves like Gherkin Towers. Nothing of the house can be seen. Whitefield House isn’t listed in the modern telephone directory; it’s too posh to hear as well as to see. The fancy foliage sits morose and fat on top of the hill. It’s a suitable place for a retired Prime Minister.

The fields to the left of the woodland slope gracefully down, and up again – another copse here, with two houses cut back into the trees – and down, alongside the train tracks to the incinerator tower of Addenbrooke’s Hospital.

After that, with a thud, Cambridge.

‘You’ve found yourself a proper mystery here,’ said the archivist. ‘Your woman may have been thrown in a skip after she died, but if this place is anything to do with her, she certainly didn’t begin that way.’

When I got back from the library I sent a postcard to Whitefield House. There was no reply. Two weeks later, driving back from London and slightly irritated, I decided to call unannounced. I pulled off the motorway and drove along the old London road that runs into Cambridge from Linton, the village where my parents first rented a house when they arrived in England in 1966. I was in the mood for ancestors.

As you approach the city from this side, it’s a surprise to discover that it is made from trees. Recognisable buildings – the University Library tower, the chapel spires of King’s and Jesus, the hump of the Anglo-Saxon castle in the north of the city – emerge from the canopy like islands.

In the far distance I could just make out the tower of my own college, St Edmund’s, where I had gone as a distinctly second-rate mathematics student, as a graduate. It was where I first met Dido, and next-door to where she and Richard had discovered the diaries.

The ridge supporting Whitefield is south of Cambridge. A quarter of a mile before you hit the city, a road turns left along Hinton Way. It rises gently, cutting a diagonal slice past a row of furtive bungalows that look as though they’re slouching up to the woods for a booze-up. I pulled over beside a farm gate. I was only a few hundred yards from Whitefield House.