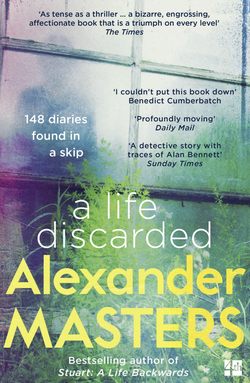

Читать книгу A Life Discarded: 148 Diaries Found in a Skip - Alexander Masters, Alexander Masters - Страница 14

7 Wor

ОглавлениеAged eighteen(?)

After an afternoon of studying the diarist, I put all the volumes back in their boxes exactly as I had found them: the old Cannings diary with its great project – the ‘it’ that MUST BE DONE!! – into the Ribena crate; the lurid modern books with their air of banal murderousness into the thigh box; the seven pads of drawings. I felt it was vital to preserve the order of the books in the boxes – as though even their arrangement captured something living and as yet unknowable about the diarist.

It was as I was about to put the first Max-Val pad of cartoons back into place that I realised who Clarence was. Flicking through the pages one last time, I stopped at a baffling episode in which Flatface (as ‘Clarence’) is out of prison and walking around a monastic courtyard.

One of the other characters is called Brakenbury. Brakenbury and Clarence? Hang on, isn’t that Shakespeare? Malmsey wine? Clarence must be the Duke of Clarence, the butt of Malmsey man. The room Flatface lives in with the Keeper and Worful is therefore the condemned man’s cell in the Tower of London. Yes, look! Here it is: Richard III … Duke of Clarence, brother to the king; Sir Robert Brackenbury [spelled with a ‘c’ in the middle], Lieutenant of the Tower … and there, the last name in the list, right at the end of the splendid round-up of extra parts: Bishops, Aldermen, Citizens, Soldiers, Messengers, Murderers, Keeper – the boy with a jaw like a casserole pot.

(‘Wessar’ is ‘I’s word for (I think) ‘bottom’.)

Shortly after Brakenbury appears in the cartoon strip, the point is absolutely settled, because in comes Richard himself, looking remarkably like Laurence Olivier:

That’s what this is! These strange figures are the actors from the 1955 Olivier film of Richard III. The one with the sparse, angular street scenes and Olivier’s lizardish king. Clarence is played by John Gielgud.

The reason for the baffling shifts in time in the comic strip is because the modern scenes are showing John Gielgud when he’s off set. For example, when he’s waiting to go to his brother Irwin’s lavatory:

Irwin: “Damn it all, John, he’s gone and pinched “Pride and Prejudice”, and he’s !!” John was more amused than sympathetic.

or being chased by eggs (‘I’s word for women):

“I’d love to come out with you Johnnie,” said the egg.

The young diarist is bewitched by John Gielgud. The actor’s face does not vary because it is a perfect denotation: those nine lines and the sprouting of hair are her hieroglyph of love.

Forgot to put in diary, that on Monday night – or rather, Tuesday morning, a swerb dream of Clarence in his brown gown, lying on the ground, weeping, with his head on his sleeve – a vague & c-feel [arousing] & swerb dream. Bother my duties – eugh. Want to have a fling!

Other exercise pads and jotters that I’ve discovered since contain attempts to start a novel about Gielgud. It’s an explosive story. Things constantly happen ‘suddenly’. People are repeatedly unexpected. Several times per page a narrative hand pops out and slaps the reader across the face:

John still felt upset, so accordingly partook of a great deal of Dry Martini, more than was perhaps good for him. His sense of injury and self-disgust began to melt away under the soothing effect of the drink and the stimulation of gay companionship. Irwin was also by now very cheerful, becoming more genial and expansive every minute, and waiting continually on Fleurette Blabbage, who proved herself to be extremely fond of shrimp-olive compote and exceptionally fond of mixed cocktail. The egg actually grew quite condescending and gracious after a session of these influences.

“Everyone, listen, Mr Gielgud says he will play to us. Isn’t that charming of him?”

John took up a volume of Beethoven’s sonatas. The place fell open, as if by itself.

“What a messy page,” remarked Fleurette Blabbage.

“That’s fingering,” Val [John’s other brother, both in this story and in real life] informed her. “He’s practised this one a lot.”

John smiled at them, and put the book up to the rack. His hands stretched hungrily over the keys. Then he began to play.

A simple, delicate, singing melody, touched with magic, passed from the piano to the listening room. Fleurette Blabbage’s cynical grin faded. Clunes [Alec Clunes, who played Hastings in the Richard III film] leant forward intently. Suddenly Baker listened too. Irwin made a face. And as for John he forgot them all, and his troubles, caught in a spell of sound, in the world of black and white, and undescribed colours, and the infinite. His playing was soft and dreamy; all of a sudden it changed. It grew wild and impassioned. John too. They all started up, with a certain sense of shock. Irwin stopped making faces. After all, John wasn’t a bad player – almost good.

Then the first theme returned again. It was like a legend, remote, sounding through distant years. It was magic, mystical. John’s playing gave it that quality.

No one paid any attention to Fleurette Blabbage. The egg was gazing at John Gielgud with all her heart. Her large eyes rolled over his face. With them she traced his curling hair, large nose, firm mouth, and stern Gielgud lines.

“Mr Gielgud!” the egg suddenly yelled leaping to her feet. “Stop that at once! What a row! My poor ears! All the notes are wrong!”

‘I’ is a better artist than a novelist. The drawings can seem clumsy, as though she drew them in a deliberately primitive and rushed style, but they didn’t end up in a skip because of her lack of talent. She has an excellent feel for movement and a good sense of weight and balance. There are plenty of professional artists in Cambridge who don’t have half her unexpectedness and verve but still make a living with their flaccid still-lives and sculptures with holes in the middle.

The reason for ‘I’s failure as an artist is in the drawings; but it’s not the drawings.

It’s the figure of Worful.

Who is Worful?

He doesn’t appear in Richard III. There’s no character in the dramatis personae who sounds anything like that, or in Olivier’s film. But he’s the essential foil in the diarist’s strip: the hideous, rubber-faced, cowardly, sycophantic creature who jumps after Flatface across all the pages of the cartoon, belching, vomiting, pulling repulsive faces and betraying everybody.

But Worful had the necessar torture, after all …

The only time Clarence is laughing rather than looking sanctimonious is when he’s enjoying Worful’s pain.

The answer comes in the first book of drawings. Written in large letters, in the diarist’s youthful hand, it is at the top of the first page before anything else. But this solution is easy to overlook because immediately after writing it ‘I’ crossed the explanation out, as though the revelation was too painful. It’s cost me considerable fussing with the scanner and Photoshop to get rid of the obscuring lines:

Wor is me.