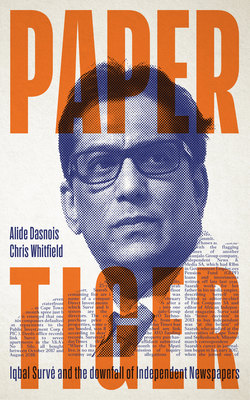

Читать книгу Paper Tiger - Alide Dasnois - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеFired

On Friday, 6 December 2013, the day after the death of Nelson Mandela, a few people on the Cape Times staff were at work. Usually no one at the newspaper worked on Fridays (the working week was Sunday to Thursday) but this was no ordinary Friday. Though there would be no issue of the newspaper on the following day, there was plenty of work to do on the editions for the following week. The Cape Times, like newspapers across the country, had prepared a detailed plan for coverage of the aftermath of Mandela’s death, from news reports and ‘colour pieces’ – writing that focuses mainly on impressions or descriptions – to analysis, photo essays and tributes of all sorts.

‘I wasn’t meant to be working, but Mandela’s death was something young reporters had been primed for, for years,’ says reporter Caryn Dolley. Another of the younger reporters, Michelle Jones, remembers being phoned by news editor A’Eysha Kassiem and asked to cover the mayor’s press conference tribute to Mandela. She arrived in the newsroom to find Dolley already there. ‘A’Eysha hadn’t asked her to be there. Caryn simply showed up because she realised it would be necessary. That was how we worked in the Cape Times newsroom,’ Jones says. ‘We worked on our days off. We showed up when we hadn’t been asked to. We did what was necessary because we loved news and we loved the newspaper.’ Together, Dolley and Jones updated the Cape Times Twitter feed and Facebook posts and decided which events each would cover.

In the editor’s office, Alide Dasnois was paging through the special four-page Mandela edition of the paper that she and her team had produced the night before. Though the other newspapers in the Independent group had chosen rather to change the first few pages and to leave the other pages untouched, Cape Town morning newspaper Die Burger and the Daily Dispatch in East London had also produced a special edition, wrapped around the previous edition of the paper.

Editor-in-chief Chris Whitfield came in. ‘Your guys did a good job,’ he said. But not everyone thought so.

Sandy Naudé, the general manager at Independent Newspapers in Cape Town, contacted Dasnois and Whitfield separately from her office on the floor above them and called them to meetings with Iqbal Survé, the new owner, at the Vineyard Hotel. The previous day the plush Newlands hotel, with its manicured lawns that stretch down to the Liesbeek River, had been the scene of Survé’s first ‘lekgotla’ – strategy meeting – with his senior staff, at which he had spoken about his vision for the newspapers and told them about himself. The Friday meetings took place in a small room on the ground floor of the hotel with some of the senior executives who had attended that lekgotla – chief executive Tony Howard, Naudé and Whitfield. Survé first wanted to discuss seconding Whitfield to a project in the Eastern Cape and giving him responsibility for the launch of new titles.

When Dasnois arrived, the meeting with Whitfield was still under way and she was asked to return in a few minutes. On Dasnois’s return, Survé asked her why she had not changed the front page of the first edition of the Cape Times to reflect Mandela’s death, instead of printing a wraparound. Taken aback, Dasnois said she did not have enough staff to remake the whole newspaper and had done her best with the four-page special edition.

‘The real problem,’ said Howard, ‘is that you led with this again,’ and he held up the first edition of the newspaper with the front-page lead about the report by Public Protector Madonsela on the Department of Fisheries contract in which some of Survé’s companies were involved. Before Dasnois could respond, Howard said that it was ‘all in the past’ anyway, and the present meeting was intended to focus on the future, including a new project for Dasnois.

Survé explained that he had decided that Dasnois’s point of view was not suitable for the Cape Times, too ideologically left and not ‘business friendly’ enough. He said he personally liked reading articles on alternative economics, but that sort of thing was not good for the Cape Times and the newspaper needed a new editor. He said he wanted Dasnois to work on a ‘Labour Bulletin’, which would include some business news, some economics and some labour coverage, and which would attract advertising from the trade unions. The new ‘bulletin’ might or might not be part of the group’s business daily, Business Report (which she had previously edited), and might instead be weekly or monthly. Dasnois would report directly to him.

Taken aback, Dasnois asked Survé when he would want her to start this project. ‘From Monday,’ he said.

‘You can’t do this to the Cape Times in the middle of the Mandela story!’ Dasnois said, aware of how disruptive a sudden change in editor would be for journalists trying to cover the biggest story of their lives.

An agitated Survé retorted: ‘Did you respect Mandela when you did this [pointing to that morning’s Cape Times]?’

‘Is that why you are firing me?’ asked Dasnois.

‘That’s not what I said,’ replied Survé.

‘You’re not being fired, we’re offering you another job,’ said Howard.

Survé continued: ‘I am the executive chairman, and as of now you are no longer editor of the Cape Times. You will not go back there, and on Monday morning at 8.30 you will report to my office. Wait – you start your week on Sunday, don’t you? Well, you can report to my office on Sunday at 8.30, and if you don’t come you will be disciplined. As executive chairman, I can do this.’

At this point Naudé and Howard suggested they all talk about her dismissal, to which Dasnois replied: ‘You probably need to talk about it without me. I think I should go now.’

Survé put out his hand but she ignored it and walked out of the room.

Chris Whitfield, still present at the meeting, was astonished. As Dasnois’s line manager, he had had no idea she was to be dis-missed. As the editor-in-chief in Cape Town, he had sometimes clashed with Dasnois over her news decisions on the Cape Times. He had been under pressure from management about falling circulations of both the Cape Times and Cape Argus and the perilous financial position of the latter. The Cape Times was losing readers in its traditional market, especially in the former white suburbs (at the time more than 50% of its readers were coloured and 30% white), and Whitfield feared that Dasnois was pursuing a new market too aggressively by shifting the emphasis in the paper towards stories from the townships. Dasnois, on the other hand, argued that these stories were of interest to all the readers of the paper, wherever they lived.

As a successful former editor of the Cape Times himself, Whitfield found it hard to sit back and watch while the paper took the risk of alienating existing readers. The exchanges between the two were sometimes sharp, and on one occasion an exasperated Whitfield said to her: ‘They say that most managers lick upwards and piss downwards. You’re the only one I know who does the opposite.’

A few days before the Vineyard confrontation Survé had invited Whitfield to a breakfast at the same hotel with Howard and Naudé, where he had begun the conversation about deploying the editor-in-chief elsewhere. At one stage the discussion turned to the Cape Times and Survé began reeling off a list of names of potential editors to succeed Dasnois. Whitfield understood Survé to be discussing an appointment to be made some time in the future – possibly after Dasnois’s planned retirement in six months’ time – but he did not believe any of them would be appropriate for the newspaper. The list included Gasant Abarder, the man who in the event would take over amid considerable controversy. Whitfield did not for a moment imagine that Dasnois might be fired within the week.

As she left the room on that summer morning after the clash with Survé, Whitfield turned to Howard: ‘Is this how we are going to treat people in the company now?’ Howard, a veteran of the company from the days when it was known as Argus Newspapers, didn’t answer.

Survé, who had left the room to make a call on his cellphone, reappeared. Whitfield says: ‘He said something to the effect that “that was my lawyer and he says I was right to do that now or she would just carry on writing crap about me”.’

Dasnois, meanwhile, was walking to her car in a state of shock: ‘I’ve just been fired. I’ve really been fired,’ she was thinking. As soon as she got home she phoned labour lawyer Jason Whyte, who was to act for her in the long legal process which followed. They discussed an approach to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration. Meanwhile, he told her, ‘Do what Survé said. Don’t go back to the office. Report to him on Sunday as instructed. And don’t talk to colleagues. But write down what happened while it is fresh in your memory.’

For the rest of that day, Dasnois dodged repeated calls from Cape Times colleagues who had no idea what had happened and who wanted urgent instructions on the coverage of Mandela’s death. Head of news Janet Heard, who was managing reporters and photographers, wanted to know from Dasnois whether to send photographer Brenton Geach to Mandela’s home in Qunu in the Eastern Cape to cover events there. ‘Around 3p.m., I still had no word from Alide, and Brenton called to say that he had been told to chat to Chris about Qunu. Strange. Something was wrong. There was indecision. No planning.’

In the late afternoon Heard and her family went to the prayer service to mark Mandela’s death at the Grand Parade. ‘Amazing sombre atmosphere. I sms’ed Alide to ask if everything was ok. “No,” she replied. I said I would try call her later.

‘We walked down Adderley Street, into Twankey Bar for a drink. I was called by NPR radio in the US to do a live link-up about the atmosphere in Cape Town that day. It went fine. Brenton called. I called Alide,’ says Heard. ‘Alide told me she had been fired from the Cape Times with immediate effect, not to return to the office. Chris was to take over as editor for Sunday. I was devastated.’

On Saturday morning Chris Whitfield was at his Rondebosch home when his mail inbox pinged. It was a letter from Sekunjalo’s lawyers, ENS Africa, addressed to Whitfield and copied to the email addresses of Dasnois, Gosling and Howard.

Dear Sir,

RE: SEKUNJALO INVESTMENTS LTD

We write to you at the instructions of our client Sekunjalo Investments Ltd.

We refer to the reporting in the 6 December 2013 edition of the Cape Times concerning the release by the Public Protector of her final report into the award of the tender by the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) to the Sekunjalo consortium.

Our instructions are that you have reported extensively over the past two years on the allegations by the disappointed bidder Smit Amandla and Mr Pieter van Dalen of the Democratic Alliance regarding Sekunjalo’s role in the award of the tender for the management of the research and patrol vessels of DAFF.

Our client has instructed us to record the following:

a.It has been alleged that Sekunjalo Investments Ltd is guilty of corruption; that it misled and/or defrauded DAFF; that it lacked the experience and expertise to undertake the management of the research and patrol vessels of DAFF; etc.

b.These allegations have been thoroughly debunked.

c.The report by the Public Protector clears Sekunjalo of all wrongdoing.

d.It would have been appropriate, after months and months of sustained attacks on the integrity of Sekunjalo, if the Cape Times had published on its front page the more accurate articles which were buried on page 18 of Business Report of 6 December 2013, that Sekunjalo had been vindicated, and that the company demanded an apology.

In the premises our client demands a front page apology on Monday 9 December from both the newspaper’s editor Alide Dasnois and the journalist concerned, Melanie Gosling, and that proper prominence be given by the newspaper of the findings of the Public Protector concerning Sekunjalo.

It is only appropriate given the history of aspersions cast on the company.

If you fail to accede to this demand, Sekunjalo will issue summons on Tuesday against the individuals concerned in their personal capacity, as well as against the newspaper, for the recovery of damages suffered by the company.

The company will also lodge a complaint with the Press Ombudsman for breaches of the Press Code if this demand is not met.

Kindly be guided accordingly

Yours faithfully,

ENS AFRICA

Whitfield could not believe his eyes. He tried to phone Howard but could not reach him. Meanwhile, he had to edit the Cape Times the next day. He had been editor of the newspaper from 2001 to 2006, but this time his editorship would last exactly one day.

Melanie Gosling remembers that Sunday. ‘I walked into the Cape Times expecting much of our day to be taken up with the story of Mandela. There was still so much to be told,’ says Gosling. ‘As we usually did with big stories, I expected a special morning conference of brainstorming with editors and reporters about new angles, who was to do what, and the general buzz and activity that goes with a big story. It didn’t turn out that way – at least not for me.

‘As I walked in, I was surprised to see Chris in his office. He never worked on Sundays. And, even stranger, the general manager Sandy Naudé was in the office with him. Management was definitely not seen in the newsroom on Sundays. I wondered what was going on.

‘Then as I put my bag down at my desk I saw Alide’s office was empty. I turned to the other reporters and asked where Alide was. They said they didn’t know. I asked how come Chris was at work on a Sunday. They didn’t know either.

‘I soon found out. My phone rang and Chris asked me to come to his office. I walked down that strip of ugly brown nylon carpet that clashed with the blue, feeling a twinge of apprehension that comes from a sense of things not being quite right.

‘I went in and Chris laid it out. It was the Sekunjalo story. Iqbal Survé had fired Alide. He was threatening to sue her, to sue the Cape Times, and to sue me – unless Sekunjalo got what it demanded: a front-page apology from Alide and from me the next day.

‘I was stunned. What on earth? Alide fired? Me sued? All this because of the story on the Public Protector’s findings on the DAFF tender to Sekunjalo? I could not quite take it in. Alide had been fired because of my story. ‘But what was wrong with my story?’

‘“There’s nothing wrong with it,” Chris replied.

‘The company lawyer Jacques Louw had since been through my story, and through the Public Protector’s report, and had told Chris that there was nothing wrong with it.

‘“Jacques is with Iqbal now, trying to work something out,” said Chris.

‘So many questions were flying through my mind: Was Alide really fired, never coming back? Or was it just a fit of temper on Survé’s part? Who would edit the paper? Would I be forced to publish an apology? I would never do that. But would the paper do so anyway, in my name?

‘“So what do I do now?”

‘“Nothing for the moment,” Chris said. He would come and address the staff about Alide.

‘I walked back across that stretch of ugly brown carpet to my desk, and went into my emails to find the letter from Sekunjalo’s lawyers. I read through Sekunjalo’s complaints, and its demands. I had had threatening lawyers’ letters before – what journalist hasn’t? – but I had never had a letter from my own newspaper company threatening to sue me. A newspaper owner suing its reporters?

‘I stared out of the window at the Greenmarket Square traders. Everything looked the same as usual, but there was something that for me had changed forever.’

At 11a.m. Chris Whitfield called together the newspaper’s staff for the usual morning conference. ‘Chris told the staff that Alide had been fired as editor. There was a stunned silence,’ says Gosling. ‘Reporters, photographers and subs stared at him, then at each other, trying to take it in. Then came the questions. Why had she been fired? Was it for real or would she come back? What would happen to the Cape Times? Who was going to be editor? Chris answered as best he could, and told us he would edit the Cape Times for the time being, and that despite what had happened, he knew the newsroom would carry on and bring out a good paper.’

‘There was shock, tears, disbelief,’ says Tony Weaver. ‘We went about our jobs, numbed by events, but journalists are journalists – when other people mourn, we report their grief, when disaster strikes, we roll into work mode.’

‘We produced a fine paper that day, miraculously,’ says Heard. ‘We pulled together. Delivered a cracker diary. Fortunately we had loads of banked stories in our holding queue.’

After the 11a.m. meeting Whitfield asked Tony Weaver to come into his office: ‘Read this … never in my life,’ he said, giving Weaver a printout of the letter from ENS Africa.

‘I can’t do it. I am going to have to resign.’ However, Weaver persuaded him to wait and to address the issue with senior management.

Whitfield phoned Howard and told him about the letter and said that he would not be running the apology. ‘Let me talk to him [Survé],’ said Howard. ‘I’ll get back to you.’ He never did. The apology never appeared and the issue was not raised by the company management again.

Meanwhile, word of Dasnois’s dismissal had ‘spread like wildfire’, says Heard. ‘We tried to get Chris to have the company release a statement about Alide. No luck. An article appeared on the Mail & Guardian website, detailing the threat of legal action, and the firing.

‘Everyone was calling us. Chris could not take calls,’ says Heard. She remembers being phoned by Raymond Louw from the South African National Editors’ Forum (Sanef) and by group political editor Angela Quintal. ‘It didn’t stop.’

Sanef was later to release a statement condemning what seemed to the organisation like editorial interference and calling for clarity.

‘It was a ghastly day,’ says Gosling. ‘Staff were shocked, bewildered and angry.’ Around lunch-time Dasnois sent the staff an email.

Dear colleagues

I’m sorry not to be with you today working on the Mandela story.

But I’m sure that whatever happens in the next few days the Cape Times team will focus on the only thing which matters at the moment: covering the Mandela story as well as we possibly can and producing newspapers which all of us will remember with pride.

Good luck with it!

Gosling replied.

Dear Alide,

We are shocked and appalled at your being fired as editor of the Cape Times.

I am sorry that it was over my story that you were fired, but having said that, I know you would never have allowed the Cape Times not to carry the story – whoever might have written it – because we would not have been doing our jobs as journalists.

Your being fired is dreadful for you personally, and for the Cape Times of course, but it has far bigger – and frightening – implications for press freedom in this country.

Everyone here is rooting for you, and there is not a single staff member who does not want you back where you belong – at the helm of this newspaper, the oldest daily in South Africa.

A comment on the cover of Gerald Shaw’s history of the Cape Times, which management gave us last week, makes a point which is pertinent today: ‘In addition to portraying the great dramas of the century, the book records with absorbing frankness the paper’s internal battles between editors, concerned to serve the public interest, and management …’

Today the Cape Times is working on one of those ‘great dramas of the century’, the death of Nelson Mandela, while in the background our editors are desperately fighting the owners for editorial independence.

It is a day to remember, for both those reasons, and one that I wish with all my heart will be resolved in the interests of the public good. As Shaw says, the story of the Cape Times is ‘the story of a vigorous tradition of independent journalism’. We can’t let that go.

Janet Heard remembers that at about 9.30p.m. she got a message from chief sub-editor Glenn Bownes saying that the company had released a statement that former Cape Argus editor Gasant Abarder had been appointed editor of the Cape Times and Dasnois had been removed from her post. ‘No explanation at all.’ The next morning the Cape Times carried a brief note about Dasnois’s dismissal.

That weekend marked what many saw as the beginning of a purge which Iqbal Survé was to undertake in order to turn the Cape Times and the other newspapers into vehicles for his own political and business interests. Yet news of his arrival on the scene, a few months earlier, had been greeted with relief by staffers fed up with the slow destruction of the newspapers under the previous owners and ready to welcome a new owner who promised to invest in journalism at last.