Читать книгу Paper Tiger - Alide Dasnois - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеNo trust in the future

By 2009 it was clear that INM plc, Independent Newspapers’ parent company in Dublin, was in serious trouble. The extraction of profits from the South African subsidiary to pay generous dividends to Irish shareholders had taken its toll. In 2008 INM plc paid out €98 million in dividends and in 2007 €73 million. In that year the South African operation contributed a quarter of the group’s operating profit. There was not much more to extract, in spite of the best efforts of Tony Howard and his team.

In Ireland an epic battle was raging, much of it in public, between the main shareholders, Sir Anthony O’Reilly (with 28% of the shares in the parent company) and his rival Denis O’Brien (with 26%). Partly in an attempt to fend off efforts by O’Brien to take over control, INM plc had been borrowing heavily from banks and other financiers in order to buy new assets and to buy back shares on the Dublin stock exchange. By the end of 2008 the group had borrowed €1.4 billion, of which €335 million was due within one year. A €200 million bond, due for repayment on 18 May 2009, was rolled over month by month. Speculation was that O’Brien, who probably had the money to pay the €200 million, would not do so except through a rights issue on favourable terms, which would make him the controlling shareholder, since O’Reilly was thought not to have the cash to ‘follow his rights’ and take up the shares to which he would be entitled.

Both the O’Reilly management team and O’Brien insisted that none of the group’s print assets was for sale, but it was clear that something would have to give. Rumours began to circulate that the South African company might be sold.

Rather than leave staff powerless while the future of their newspapers was being debated in Dublin, Alide Dasnois and a colleague on Business Report, Ann Crotty, decided in 2009 to launch a staff trust, with support from Tuwani Gumani, general secretary of the Media Workers Association of South Africa (Mwasa). Crotty was a very experienced and respected financial journalist known for trail-blazing critical work on corporate pay published during Dasnois’s editorship of Business Report.

Their idea was simple: create a trust which would represent the interests of staff – all staff, not only journalists – and which could approach funders for credit to finance a 25% stake in Independent’s South African operation when the Irish owners did decide to sell, as it seemed they would have to do. The loan would be paid back over time through dividends. No staff member would have to put in any money, and no staff member would get any money out. Once the loan had been repaid, further dividends could be used for staff training, scholarships or similar initiatives. A 25% stake in the company would guarantee the trust a seat on the board and give staff a voice in the company’s future. This would set a precedent in South African media. Although under the Irish owners Independent managers and editors had been issued shares in the listed company as part of their pay packets, the general staff had never had any meaningful stake.

Crotty floated the idea to colleagues, who responded with interest. A blog was started to keep in touch with staff and Archbishop Desmond Tutu agreed to be the patron of the trust, sending a message for the blog on 31 August 2009: ‘I am honoured to be your patron. We know that the price of freedom is eternal vigilance and at this particular stage in our nascent democracy more than ever we need a free and independent press. The powerful are kept on their toes most often by the knowledge that any excesses and abuse of that power will be fearlessly exposed. You are absolutely crucial. All power to you all. God bless you.’

Gumani formally informed local CEO Tony Howard about the establishment of the trust at the beginning of June 2009, and sent out a statement the following month, announcing that Mwasa was involved in setting up a staff trust in the South African company. But the statement was met with a hostile reception from Independent’s South African management. Editorial director Moegsien Williams emphasised to Dasnois that the company was not for sale. She explained that the plan was to have a trust in place in case the controlling shareholders decided to sell, so that journalists would have a voice in any future discussions about the ownership of the company.

Crotty wrote to O’Brien on 12 August 2009, suggesting the sale of a stake in INMSA to the trust. ‘While the sale of a stake to a journalists’ trust would reduce INM plc’s cash flow from the SA business, we believe it would be justified in terms of the long-term value that the project would create. It would also deal very effectively with any concerns about under-investment in an industry that plays a critical role in this country. In addition, given that the terms of the trust would include a commitment to editorial independence it would also deal with any concerns South Africans might have stemming from possible changes within the control structure at INM plc.’

O’Brien responded a fortnight later, telling her that he was in the process of ‘trying to help restructure the balance sheet’ of INM plc and could not comment.

Meanwhile, the Irish Times reported on 25 September 2009 that O’Brien, described as a ‘rebel investor’, had offered the banks €100 million upfront in return for a majority stake. INM had fought off the offer, the Irish Times reported, and had said the company was close to an agreement with the banks. INM plc had also fought off an attempt by O’Brien to stop annual payments of €300,000 to former chief executive Tony O’Reilly, now ‘president emeritus’.

The board went ahead with its own debt-for-shares swap in November. By the end of the operation, the creditors held 47% of the shares in INM plc, and the stake of the O’Reilly family had been slashed to 14% and that of O’Brien to 13%. Creditors also agreed to an extension of repayment terms for other debt. For now, disaster had been averted. But the company was still not out of the woods, and another rights issue was planned for later in the year, to raise the remaining €94 million of immediate debt.

In the meantime, Crotty and Dasnois continued their discussions with staff and potential funders, working on an estimate of R500 million for a 25% stake in INMSA. One of the possible funders was the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), which invests on behalf of the giant Government Employees Pension Fund. Crotty had met PIC head Brian Molefe in October 2009 and the trust had sent a serious proposal to the PIC. Trustees told colleagues in November: ‘We believe that the profile of the … trust that we have in mind would represent an ideal empowerment shareholder for INMSA.’

Matters were to be left there for the next three years, until INM plc once again found itself up against a mountain of debt – and this time it seemed there would be no way out. O’Brien won his battle against the O’Reilly family, kicking out Gavin O’Reilly in April 2012, three years after his father, Sir Anthony, had been ousted. Gavin O’Reilly collected a €1.87 million exit package, and Vincent Crowley was appointed chief executive. He launched a whole new programme of cost cutting. He also closed the INM head office in Dublin and the company’s London office, and implemented a redundancy scheme at the Sunday World newspaper in Ireland. In Cape Town, Newspaper House had already been sold (in 2011), and the R90 million proceeds shipped home to Ireland.

But in spite of all this destruction, the debt reduction was very slow and by June 2012 it seemed that the parent company would have to sell off bigger assets to pay off part of the debt. O’Brien now had just under 30% of INM plc. By June 2012, Irish newspapers were reporting that he wanted to sell the South African operation and spend the money on the company’s Australian ventures. For the first time, the sale of INMSA was officially on the table. And bidders were not slow to respond.

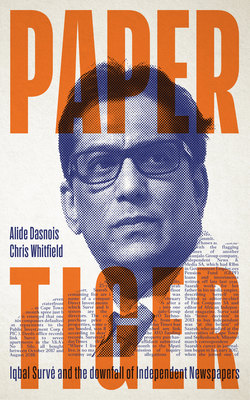

The Irish Times reported on 15 June 2012 that ‘Sekunjalo Investment Holdings, which has as its CEO former African National Congress (ANC) activist Iqbal Survé, is said to be putting a bid together; while so too is ANC-linked businessman Cyril Ramaphosa of Shanduka Investment Holdings’. On 10 July, the Financial Times reported that INM, described as ‘the indebted Irish media group’, had appointed advisers to work towards a sale of its South African publishing business. Sekunjalo and Shanduka were again mentioned as possible bidders.

It was time to revive the idea of the staff trust. Crotty, Dasnois and Gumani had brought Gordon Young, investment adviser to black empowerment group Ditikeni, on board. Young agreed to advise the trust in exchange for a small stake in INMSA for Ditikeni.

Crotty and Dasnois approached staff again, pointing out that ‘there has recently been a change of control of the Independent News and Media Group in Dublin. The new controlling shareholders appear to be keen to sell INMSA. They have already appointed advisers to assist them. This provides us with an opportunity to seek a shareholding in INMSA.’

Once again, reaction from INMSA management was hostile. On 29 May 2012, group editorial director Moegsien Williams flew to Cape Town to warn Dasnois to stop ‘sowing discontent and uncertainty’ among staff through the idea of the staff trust. Williams told Dasnois that she must not use company resources or company time to send information to staff about the trust, and she must not ‘embarrass’ the CEO or ‘put him in a difficult position’. If she continued to do so, the company would have to ‘look at taking action’. ‘We are very serious about dealing with this matter,’ he told her. In a follow-up letter sent to her on 1 June, Williams emphasised: ‘The company has not been put up for sale, and while you are in our employ, we expect you to further the company’s best interests.’ She was then handed a written warning not to disregard his instructions on the matter.

Though the ban on communicating through workplace channels made it harder for the trustees to stay in touch with staff, discussions with staff members continued, and Crotty, Dasnois and Gumani organised meetings in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban. Staff members who had stood by powerless during the destruction of the O’Reilly years welcomed the chance of a stake in the future and signed letters of support.

As the trust had no funds, Crotty and Dasnois paid for air tickets, blog development and the registration fees of the trust out of their own pockets. Work on the trust deed was done pro bono by the firm of lawyers ENS. The trust was registered in December 2012 as the Independent Trust for Media Freedom, with Gumani, Crotty and Dasnois as its founding trustees. The trust deed stipulated that new trustees would be elected by members within 120 days of the trust’s registration.

The trustees and Young also engaged in talks with several people who were officially or unofficially interested in a bid. One of the bidders they met, in a Rondebosch cafe in July, was Iqbal Survé, who was going to Ireland a few days later. He did not discard the idea of partnering with the trust, but set the limit of a staff shareholding at 10%. In a letter to the trustees and Young on 15 July, thanking them for the meeting, Survé said he was looking forward to working with the workers’ trust. ‘Hopefully we can do something together.’

He attached to the letter the latest edition of Leadership magazine which contained a long article about him. This, he said, was because his decision ‘to remain outside the public eye’ for the previous few years had ‘created a lot of mystique’, and the article might ‘demystify who I am since it helps to set aside any speculation’.

Crotty replied on 17 July that Survé’s proposed stake of 10% for staff ‘does not accurately reflect the full value of the considerable intellectual capital that our staff trust brings to any bid to buy out the South African assets’, but that the trustees were happy to keep talking. The fact was that Crotty, Dasnois and Gumani were reluctant to throw the weight of the trust behind Survé – whose bid might not succeed – for anything less than a promise of 25%.

Survé wrote to Crotty on 24 July 2012 to say he had appointed advisers and was ‘confident of our position’ relative to rivals and wanted to finalise the partners in the consortium. He asked for the names of all the participants in the trust. He also said that ‘another group of former and current Independent employees’ had formally presented their credentials ‘and are now included in our consortium’, and he tried to pressure the trustees into a commitment. Crotty replied on 25 July that the trust was unable to accommodate his deadline. Much later, it was to become clear how much this had angered him.

Meanwhile, in September INM plc reported very poor interim results, with expectations that the second half of the year might be as bad. INMSA’s contribution to group profits had dropped by 34%, partly because of the closure of the Cape Town printing operation and the drop in commercial print revenue.

The company noted that several parties had shown interest in acquiring the South African operation and said that this was being considered. CEO Crowley indicated that the sale of INMSA could halve the group’s debt level of €423 million, implying that the South African company was valued at around €210 million, or approximately R2 billion at current exchange rates.

There was now speculation that a second undisclosed bidder – Sekunjalo being the first – might be the Gupta family, rather than Ramaphosa. The Guptas were to become notorious in South Africa for their role in ‘state capture’ – the use of corrupt politicians to access state resources.

As Investec was advising INM plc about the sale, Gordon Young approached Investec on behalf of the trust, asking to be kept informed and to receive the memorandum of confidential information sent to other bidders. In response, Investec asked for proof of support for the trust from staff. But the trustees were concerned about possible victimisation of staff members who supported the trust. Instead, they asked Mwasa, which had 393 members or 28% of all staff, and the South African Typographical Union (Satu), with 161 members or 11% of all staff, to send letters of support for the initiative to Investec.

Crotty told Investec on 11 November: ‘We are not prepared to give INM a copy of the list of employees who have signed in support of the trust … During the past ten years there have been frequent retrenchment exercises at INMSA – even during periods of strong profit growth – and this has created a general sense of insecurity amongst employees. Because of this we felt it was necessary to provide staff with some comfort that their names would not be disclosed to management of INMSA. Our desire to provide this comfort was heightened by the animosity towards the Staff Trust initiative that, rightly or wrongly, employees sensed from top management – certainly Alide Dasnois and I both felt our continued employment at INMSA was under threat.’

On 13 November 2012, the trustees were able to update staff on developments. ‘There is apparently a short-list of three interested bidders; it is unclear who they are but the speculation is that Iqbal Survé’s Sekunjalo is one of the three. [The mining magnate] Patrice Motsepe might also be involved in a bid. In addition there is speculation that [businessman] Muzi Kuzwayo is part of a group that may be making a bid.

‘The Guptas apparently remain on the sidelines at this stage; their offer of approximately R1.2 billion has been deemed too low to be considered. If the other parties do not make a firm offer above this level or if the Guptas can be persuaded to increase their offer, they will be brought back in as a potential bidder.’

Meanwhile, staff were getting very worried as the process of profit extraction accelerated alarmingly. Staff vacancies were frozen, putting even more pressure on those who were left. Merit increases and re-grades were also put on hold, with serious effects on staff morale. Freelance budgets were cut even further, though newspapers had been relying on freelance contributions because of previous staff cuts. Editors were under pressure to reduce the number of pages per edition to save printing costs; urgent decisions – on the future of internet and mobile coverage, for instance – were put aside, while competitors moved forward. At the same time, cover prices of the newspapers were raised again and again, in an attempt to make short-term revenue gains. Deteriorating news coverage, combined with smaller editions and higher prices, led to tumbling circulations.

By December 2012, as speculation continued to circulate, there seemed to be only two bidders left in the race: a consortium that included Patrice Motsepe – and Sekunjalo.