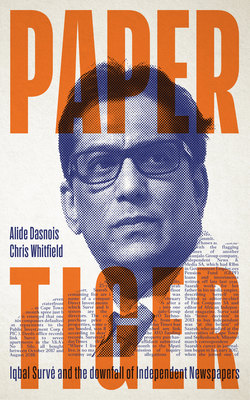

Читать книгу Paper Tiger - Alide Dasnois - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеProfits of doom

It was a warmish spring evening in 2006 when Independent Newspapers held its International Advisory Board (IAB) banquet at the Castle in central Cape Town. Chris Whitfield was standing at the end of an arcade, smoking a cigarette, away from the crowded tent inside the Castle walls where the thousand or so guests were milling about. A loud voice alerted him to an animated discussion taking place between two men further down the arcade.

Sir Anthony O’Reilly, the ageing yet still imposing Irish billionaire and proprietor of Independent Media, was vigorously poking his finger at that day’s edition of the Cape Times and the tone of his voice suggested he was very angry. Opposite, framed by the arches, was Tony Howard, chief executive of the South African arm of the company. Howard, a slight man with heavy spectacles below a mop of dark hair, was taking a beating.

Howard turned and noticed Whitfield. The CEO’s hand rose and pointed towards him. O’Reilly stuffed the newspaper into Howard’s hands and the agitated CEO strode rapidly down the corridor. ‘Sir Anthony wants to know why the Cape Times used a picture of [former Canadian Prime Minister Brian] Mulroney with the story about the IAB,’ said Howard.

‘And …?’ responded a puzzled Whitfield.

‘He is in the story and the picture should have been of him.’

With that Howard headed off into the tent. Whitfield was bemused. For a start he was the editor of the Cape Argus at the time, not the Cape Times, and had no authority over the latter paper’s editor or staff. It seemed he had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Two days later Whitfield was given another reminder of O’Reilly’s ego and his sentiments about the newspapers. The Cape Argus had that day published an article on the IAB and illustrated it with a small head-and-shoulders photograph of O’Reilly, drawn from the files.

Howard phoned him late at night – Whitfield was in bed, reading – to tell him that ‘the old man is not happy about the picture’. O’Reilly had been on a diet and the picture in question showed him carrying some weight. Whitfield was told to have the photographers go through the picture library and remove all those images in which Sir Anthony might appear overweight.

Generally, though, O’Reilly and his managers steered clear of editorial issues. The real damage inflicted by the Irish was more insidious, and often at the hands of a South African management keen to please its foreign bosses. A senior Irish executive once said to Whitfield with a laugh: ‘We ask them to jump, and they ask: How high?’

In 1993 the Irish investors – Independent Newspapers plc (INM) – had bought what was then Argus Newspapers and its titles from Anglo American Corporation.

They then swept into the company with a swagger that caught many of the staff by surprise, their manner being in such sharp contrast to the benign and generally hands-off approach of Anglo. First through the door was one Chris Tippler – an Australian consultant who was immediately branded as being the ‘Irish’s rottweiler’, a characterisation which he did not like. ‘Newspapers are like slot machines – get all the bits in the right place, pull the handle and the money comes pouring out,’ he once told Whitfield at a meeting in his Sandton hotel room.

Ivan Fallon, a flamboyant man with a pronounced upper-class British accent, was appointed chief executive officer and set about carving up the company. Within months he had launched a national business supplement – Business Report. Sometime later the group’s wunderkind, Shaun Johnson, was given the task of launching a new, quality Sunday title, the Sunday Independent.

Business Report was launched with great fanfare in Johannesburg. A light show was beamed onto neighbouring buildings from a city-centre rooftop as the country’s leading businessmen and politicians looked on. It was evident that the Irish were intent on burying ‘Aunty Argus’ – the old grey company of Anglo American.

The Sunday Independent was launched on 26 June 1995. The lead story was South Africa’s Rugby World Cup win of the previous day. The company now had thirteen titles in five cities: The Star, the Saturday Star, the Sunday Independent and Business Report in Johannesburg; the Pretoria News in Pretoria; The Mercury, the Daily News, The Post and the Sunday Tribune in Durban; the Cape Times, the Cape Argus and Weekend Argus in Cape Town as well as a suite of free community newspapers; and the Diamond Fields Advertiser in Kimberley. Later, the tabloid Daily Voice in Cape Town and the very successful Isolezwe and Isolezwe ngeSonto in Durban were to be added to the collection.

For Johnson, Whitfield and the others involved in the new projects, it was a time of great excitement, but there were indications of less savoury things to come: the managers of the new company – now named Independent News and Media South Africa (INMSA) – were evidently going to keep a very close eye on the bottom line.

After the honeymoon period the owners took a sharp knife to the company’s costs. In July 1994 the Argus Africa News Service was closed after 38 years of covering the continent. The Irish management said ‘new arrangements’ would be made to cover the rest of Africa, but little ever materialised. In September 1994 the Pretoria News was turned from an afternoon paper to a morning edition and its printing press was moved to The Star’s premises in Johannesburg – a move that the Media Workers Association of South Africa (Mwasa) said ‘resulted in scores of job losses chiefly amongst printers, but also journalists and administration staff’.

Further cost-cutting plans were revealed in a series of meetings in which editors were told how badly their titles were performing. Improbable ‘benchmarks’ were constructed for just about every line in the budget and editors were directed to achieve them. Newsrooms began to shrink, juniors were bought in to replace more experienced and expensive writers, ‘centralisation’ and ‘synergy’ became buzzwords, and editors were made accountable for the business performance of their titles. This intensified when Howard took the reins from Fallon. According to company legend, he kept a graph in his office which compared the profits he delivered with those of his predecessors.

Soon editors found it virtually impossible to get the go-ahead to spend money. Howard’s weary lieutenants eventually took to giving permission behind his back. The entrepreneurial spirit which Fallon had introduced disappeared and any new idea was regarded with wariness or suspicion. Trends that were sweeping world media, most obviously the migration to digital platforms, were ignored.

Editors’ roles soon became complicated: on one hand they were trying to bring out credible newspapers, on the other to protect their dwindling resources from the cost cutting. Many were victims of the so-called boiling frog syndrome. The changes were incremental and often quite subtle – or hidden – and it was only with the perspective of time that they realised what had been done to the newspapers.

Moshoeshoe Monare was the editor of the Sunday Independent during the last years of the Irish ownership. ‘My impression was of proprietors and shareholders who had stopped caring about the business and the country and focused on return on their investments,’ he recalls. ‘With their European and other businesses facing decline, South Africa became their cash pot and they tried to extract as much as possible without any consideration for future investments, innovation or growth.’

But the positive aspect of this, he says, was that ‘they did not directly interfere in the editorial content in so far as it related to local politics. Editors enjoyed freedom to edit their papers as long as circulation and revenue satisfied the Irish greed. But the trade-off for editorial independence,’ says Monare, ‘was lack of investment or any form of retention or other rewarding schemes for editors and staff.’

In 2011 the National Treasury decided to launch a debate about foreign investment in South Africa. A discussion document called ‘A review framework for cross-border direct investment in South Africa’ was published, and interested parties were invited to respond. Mwasa replied with a ‘case study’ of Independent Media that highlighted its concerns. ‘Some 18 years after that initial investment in SA it would be hard not to conclude that INM’s ownership of the largest newspaper group in the country has made few of the contributions that are expected from foreign direct investment. Specifically the initial net investment of an estimated R560 million to R725 million has been dwarfed by the possible outflow of much of the local operations’ profits.’

While the company was listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, said Mwasa, the outflow was limited to dividends, management fees and interest payments. But when the Irish parent company bought out the other shareholders and the South African company was delisted in 1999, ‘the scope for repatriation of profits to Ireland was considerably enhanced’, Mwasa said.

‘In the period between 1999 and 2010 operating profits are estimated to be in the region of a total R4 billion. During that period operating margins were increased from 12.5% in 1999 to 21.1% in 2010 … Far from boosting employment opportunities, the ownership by INM has been accompanied by a significant reduction in employee numbers. From a high of 5,223 at the time of the initial transaction in 1994, employee numbers have been reduced steadily to a current level of around 1,500.

‘The ongoing severe pressure to repay debt owed by INM plc ensures that operating margins remain under considerable pressure in South Africa as profits generated by INMSA are used to repay the Irish debt. This situation is merely an extreme version of the 18-year-old practice of extracting profits from South Africa regardless of what was appropriate for the South African trading environment.’

The trade union concluded by noting that a local owner of South Africa’s largest print media group which had merely spent or invested the proceeds of 18 years of profits, had not slashed employee numbers, and had made adequate tax payments, would have benefited the country more. In addition, South African ownership might have involved black economic empowerment and prepared the group for ‘the complex and volatile future facing the media industry’.

The consequences of this profit extraction were evident in the newsrooms. Little by little, what could be cut was cut. The newspapers’ libraries – where years and years of cuttings and photographic prints were stored for the use of journalists and the public – were shut down. Political coverage was centralised into a single Political Bureau, serving all the newspapers. Sub-editors were moved from the staff of individual titles into a common pool – the Independent Production Unit – where they worked on a conveyor belt system, picking up stories from an ever-running queue, with little regard for the different styles and personalities of the newspapers. Conscious of the damage this ‘one size fits all’ approach would do both to staff morale and to the look and personality of the newspapers, Whitfield and other editors – notably Alide Dasnois’s principled and popular predecessor on the Cape Times, Tyrone August – resisted the creation of the Independent Production Unit, but failed. August resigned shortly afterwards.

Hardly a week passed without some new cost-cutting plan from management, some of them ludicrous. (One suggestion was that the vital Reuters wire feed be cut.) First in Cape Town, then in Johannesburg, the printing operations were closed, with the loss of 350 jobs, according to Mwasa. For the first time in more than a hundred years, Newspaper House in Cape Town no longer throbbed in the afternoons and early mornings when the huge presses were switched on, spewing out newspapers for loading onto the big trucks which blocked the traffic in Burg Street.

Finally, the historic old building itself was sold and INMSA leased back a few floors from the new owners. The Cape Times, Cape Argus and Weekend Argus were housed on the fourth floor, and it was not a happy place. The editorial computer system – bought on the cheap, according to rumours circulating among journalists – would frequently break down, causing sub-editors to swear furiously as careful work was lost, and prompting ever angrier calls to the overworked emergency technicians. Each change to the computer system seemed to staff to be designed to increase rather than to decrease their workloads.

Perhaps the single greatest source of anger in the Cape Town newsroom was an air-conditioning system that alternated between freezing cold and blasts of heat if it was working at all. On summer evenings journalists never knew whether they would have to wear jackets at work or sit in a stifling atmosphere with little air circulating. Cape Times chief sub Glenn Bownes would explode: ‘I can’t f****** work like this.’ His sentiments were shared by most on the floor as they fought over decent chairs and wondered if the grubby carpet would ever be replaced.

On 2 June 2009, in response to a message from Tony Howard to staff about ‘tough trading conditions’, Alide Dasnois wrote to him summarising the situation on the Cape Times. She said she had worked on five of the group’s newspapers, on three of them as editor, and had ‘witnessed the relentless stripping away of the capacity of those papers to offer the quality journalism which our readers demand and deserve’.

Reporters on the Cape Times were routinely writing three stories a day, she said, often conducting interviews by telephone; the paper was battling to retain top-quality journalists because of poor salaries and interminable promotion processes; it no longer had features writers or features editors; the books page was put together by the editor’s PA; the paper had only one arts reporter; essential wire service pictures and copy had been lost; editors had been told to prepare pages in black and white and minimise colour to cut costs; advertising-to-editorial ratios had crept up; and the drive to maintain revenues put editors under constant pressure to accept ‘advertising which breaks all the rules’; the Cape Times could no longer afford to pay for the popular Zapiro cartoon and had to write ‘cringing letters to other contributors apologising for paying a mere “honorarium” rather than a respectable fee’.

‘Much of this,’ she suggested to Howard, ‘dates from long before the current “severe economic downturn” to which you refer. It is the result of processes put in place over the years by shareholders and executives whose goal seems to have been to extract as much profit as possible from the South African assets in order to pay out handsome dividends and bonuses.

‘What you refer to as “prudent cost management” is little more than looting.

‘As a result of all this, the Independent Group newspapers are no longer able to play the role they should be playing in the construction of our democracy. We have lost any sense … of journalism as “the first draft of history”. We are failing in our duty to our readers.

‘Little wonder, then, that our circulations are falling.’

Howard did not reply.