Читать книгу Boy from Nowhere - Allan Fotheringham - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеTo Warsaw on a Scooter

The day Don Cromie hired me I was sent to see the managing editor, Hal Straight, a frightening monster of a man of some 260 pounds. He and the now-famous Pierre Berton put out the morning edition by 10:00 a.m. and then drove to the bushes of Stanley Park and drank a twenty-six-ouncer of rye from the neck of the bottle, came back, and put out the afternoon edition. Berton being the star reporter.

As I walked into Straight’s office, I vowed I would demand $50 a week. Stupidly, I asked, “Am I worth $50 a week?”

The managing editor said, “At the moment you are not worth a goddamn cent. Forty-five dollars a week — seven o’clock Monday morning. See you.”

Straight sent me to work for Erwin Swangard, who for the first six months wouldn’t talk to me. Every Monday morning at the sports section meeting he turned to Merv Peters, his assistant editor, and said, “Tell Fotheringham to cover the lacrosse game in New Westminster.”

Peters, who was sitting about four feet away from Swangard, then turned to me and said, “Fotheringham, cover the lacrosse game in New Westminster.” He resented me because I was the only one with a university degree in the department, so he added, “Take the company car. You can drive, of course?”

I said, “Of course.”

But, of course, I couldn’t. (Remember that Chilliwack movie?) I still didn’t have a driver’s licence, so I asked my sister, Irene, who was in nursing school in Vancouver, to come with me for support.

In those days streetcar tracks ran from Vancouver fifteen miles to New Westminster. I shifted the car into second gear, put the wheels in the streetcar tracks, and drove at twenty miles an hour to my destination. My sister was so frightened that she took the bus home. I drove the company car all summer on assignments and learned to drive. Three months later I took the driver’s licence test. That was another form of learning on the job.

Years later I was in Palm Springs, California, speaking to the Canadian-American Friendship Society. I walked into the hotel, and there was Don Cromie, by now of course long retired in his winter retreat. The society had asked him to introduce me, and he told a story I had never heard.

Six months after he hired me he called Erwin Swangard in and asked, “Whatever happened to that kid from UBC that we hired?”

Swangard said, “Well, he’s lazy, he’s a troublemaker, he won’t take orders from anybody, and he’s always late for work.”

“Well, get rid of him,” Cromie said. “Don’t keep him around just because I hired him.”

“Oh, no,” Swangard said. “He’s the brightest guy in the whole newsroom and has a tremendous future in journalism.”

As a sportswriter, I covered lacrosse, hockey, and football. One person I met while covering football was a young guy named Bobby Ackles. He was the water boy for the B.C. Lions. Bobby worked his way up the ranks — equipment manager, et cetera. He then somehow was hired by the Dallas Cowboys as a scout. Bobby advanced through the National Football League ranks and eventually became a coach with the Las Vegas franchise.

The smart guy who owned the Lions, now Senator David Braley, brought him back to Vancouver and made him president where he used to carry the water buckets.

I put Bobby in touch with a ghost writer and a publisher to tell his amazing life story, which was published in 2007. He then had a boat called The Water Buoy, also the title of his book. Sadly, in 2008, he died of a heart attack on the dock at Bowen Island while walking back to his boat with his morning coffee.

At the last birthday bash for me that Bobby attended on Bowen Island in 2006 he and his wife, Kay, brought me a B.C. Lions jersey with my name and the year of my birth on the back. It is something I will remember him by and cherish.

When I graduated from UBC in 1954, I was appalled at the low wages journalists were paid, so I made a deal with myself. I vowed to stay in the business for three years, and if I didn’t reach a certain level of advancement, I’d quit and go to law school. I was within six months of the self-imposed deadline and thought I was destined to be a lawyer. Then two things happened.

Like all sportswriters, I worked at night, covering a hockey game, a football game, whatever, then came back to the office to write the story and, of course, ended up in Chinatown past midnight with the boys telling one another lies and gossip. Such a lifestyle meant I woke up at about noon and had all afternoon free. One afternoon I was at Kitsilano Beach, looking for girls as usual, when I ran into Bill Popowich, who I had graduated with at UBC where he was captain of the university soccer team.

Bill had just returned from Europe, and he changed my life when he told me his tales of youth hostels, London, Paris, Rome, and all the other delights. I wondered what I was doing sitting on Kitsilano Beach, and at that moment I decided to travel to Europe as soon as I had enough money.

Shortly thereafter there was a shuffle at the newspaper and I was offered the job of sports editor. I was only twenty-four, and that was the most unusual promotion. So I knew I could make it in the business and immediately quit and went to Europe to bum around for three years. Everyone in the building thought I was nuts. It was 1957.

I went to New York, saw Mickey Mantle play at Yankee Stadium, and took the Holland-America liner Statendam to Southampton. Onboard I met two girls who had just graduated from Vassar, the female Ivy League school. They were going on the usual grand tour of Europe and had picked out all of their hotels and restaurants in London, Paris, and Madrid. They were great fun, and when we got to London, they persuaded me to go to these fancy restaurants with them.

Me, who had saved $1,500 and was going to do Europe living in youth hostels.

One night we were in a Greek restaurant in Soho and suddenly there was a huge crush of men walking in, guarding a couple. It was Prince and Princess Michael of Kent, and I realized I was in the wrong league and told the girls goodbye.

I then took a ferry across the English Channel to begin my great adventure and bunked into a youth hostel at Dieppe. Wandering down the beach, I saw a nice little restaurant and went in to have a beautiful steak that I discovered to my amazement was very rare and bloody. It was the first time I ever knew there was blood in meat, having come from Hearne, Saskatchewan, where all meat was done to the texture of a boot.

The suitcase I was going to use for six months was so heavy that I had to take a taxi out of town to get to a highway to hitchhike. Reaching Holland, I was picked up by a magician going to a magicians’ convention. He got a flat tire, and I helped him change the tire. Some miles down the road I realized that my glasses had fallen into the ditch. So I had to hitchhike the opposite way and figure out where, in a country that had four million identical ditches, my glasses might be.

I was down on my hands and knees when a car stopped and the driver asked, “What are you doing?” I explained, and he said I would never find the glasses and to get in his car. I told him my great plan to conquer Europe by foot and he said, “Come with me.” Then he took me to his home, and it turned out he was a Vespa dealer. The dream answer to my unplanned life.

It took three days to get a two-wheeled Vespa shipped in. Because it was late in the afternoon and I wanted to get to Hamburg that night, the Vespa dealer offered to give me a lesson on the scooter. In my hurry to get out of town, I said, “No, don’t worry.” (This, of course, was in the days of no helmets being worn.)

I got about a half-mile out of town when a huge truck went by. With a blast of air, the next thing I knew, I woke up in the ditch with the Vespa on top of me. I looked up and saw four huge wooden shoes occupied by two farmers, who pulled me out.

Rain or shine, through Denmark, Sweden, and East Germany on the way to Warsaw, I had to exist with just my sunglasses. When I made it to Stockholm, I stayed with Dr. Lusztig, the Hungarian father of Peter Lusztig, my university roommate in Vancouver. I was preparing to leave Stockholm to drive back through Denmark and then into West Germany to make my way to Berlin. He told me there was a ferry from the tip of Sweden to East Germany, which would cut miles and countries off my itinerary.

I landed in East Germany with no papers or relevant documents. The authorities, after much puzzlement, gave me a one-day pass, saying I had to go straight to Berlin without stopping to get there that night.

Under a heavy rain, I was frightened to death and was speeding as fast as I could when the road suddenly changed into cobblestones. The Vespa and I parted company once more. I was just outside a farm, and the farmer hauled me into the barn while the cows stared at me strangely and mooed as he hammered the damaged scooter into operation.

This took so long that there was no way I could reach Berlin as ordered that day. So I stopped at a small inn, went downstairs for dinner, and to my horror saw three East German policemen in their ominous uniforms. The chef came over and handed me a menu which, of course, I couldn’t understand, so I just pointed at three different items.

“Nein,” he said, becoming quite agitated. And I, not wanting to cause any attention, insisted on what I had ordered. He kept shouting at me. By this time, everyone in the restaurant was gazing my way.

I understood why when he finally returned with the three items I had ordered. Baked potato, fried potatoes, and boiled potatoes. And I, knowing everyone was gawking at me, ate them all down happily as if I did that every day. The three policemen, laughing, sent over a quart of beer. Trying to escape being jailed, I sent them back three quarts. They sent me back another quart. It was a very long evening.

Because I had arranged while at the Vancouver Sun to meet a copy girl named Helena Zukowski in Warsaw at high noon on July 1, I was in a panic. She had won a scholarship to study in Poland because of her Polish heritage, and I had figured there would be a main railway station in Warsaw and obviously there would be a big clock there. Of course, that was months before I left Vancouver. I had said I would stand below the clock at high noon on July 1.

Setting out through East Germany to Berlin, I immediately found a youth hostel. I then wandered around and came upon a food fair and saw they had a money exchange. I had arranged a visa for Poland in London, and the travel agency had exchanged the money for me, enough for my two weeks in Warsaw.

The exchange rate was one grosz to the dollar and a hundred groszy to one złoty. In the Berlin exchange I found it was four groszy to the dollar. So I was suddenly rich.

After several days, I headed for the Polish border again without proper papers or visa. They were so puzzled again by this silly kid on a Vespa that they somehow let me through. On the first day in Poland I was speeding toward Poznań. The Polish rural roads were filled with chickens, pigs, cows, everything.

Late in the afternoon I came across a herd of cows crossing the road. I stopped and let all of them go by except one lonely cow trailing the herd. When I zoomed the Vespa, the cow suddenly turned around and came back across the road.

I went ass over teakettle across the cow and landed on the rough macadam road with its raised gravel. It removed two layers of skin from each of my ten fingers. There are only two levers on a Vespa on the handlebars. One is the gas and the other is the brake. So each time I squeezed one of them, blood oozed out of my fingertips.

It was 5:00 p.m. when I arrived in Poznań. Everybody was leaving their offices and lining up at the bus stop. They looked at me, this guy with sunglasses, no helmet, and a wild red beard with blood dripping from his fingertips. A man stepped out of the lineup and said, “Come with me,” and took me down an alley.

I didn’t know if he was planning on mugging me or raping me. He produced a key and guided me through the back door. It turned out he was a pharmacist. Taking me into his store, he bandaged me up.

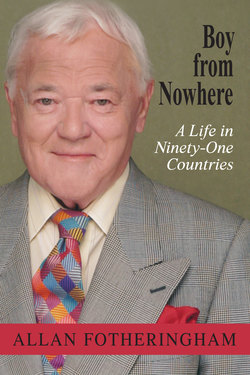

At play during my European travels.

Still trying to get to Warsaw by July 1 to meet Helena, I left Poznań early the next morning. After dropping my bags off at the Windsor Hotel in Warsaw, I went to the clock at the railway station and stood there for four hours. She never showed up. The next time I saw her, years later, she was editor of a magazine in Palm Springs, California. She apologized.

Upon returning to the hotel, my good fortune due to the exchange rate was immediately apparent to the staff. Because I had this ridiculous money that I had bought for 25 percent of its worth, I couldn’t bother with all of these hundreds of groszy that were tearing holes in my trousers. So I dumped them in a wastepaper basket in my hotel room.

The word soon got around through the cleaning women that a mad American millionaire was so rich he was throwing away money. Probably a week’s wages for them. So whenever I went down to the hotel dining room, three or four waiters attempted to elbow one another’s teeth out in order to serve me and get the tip.

Shortly after arriving, I sent a dispatch to the Vancouver Sun, which it ran on the front page. In the piece I said, in my innocence, “The secret police cannot be seen anywhere in Warsaw.” My close friend, Carol Gregory from The Ubyssey days, read this and sent a letter to the editor, stating that she wasn’t aware that people walked around Warsaw with badges on their jacket saying, “Hey, I am the secret police.”

As arranged in London, I had to have a Polish government tourist guide, and the young lady showed me all over town. By this time, I was fed up with the sunglasses and explained to her that I wanted to cut short the visit to get back to Berlin so I could buy new glasses. She sympathized with my plight and arranged for me to leave. So I left the whole country by making a profit.

Upon returning to Berlin, I met at the youth hostel a young South African architect who was doing the same thing as I was on a motorcycle. Someone who could come in very useful when years later I went to Cape Town to release Nelson Mandela from jail. We roamed around Germany together and then down to Austria. One day in Vienna, in heavy traffic, he was ahead of me and jumped the red light. I had to stop. As a result, we lost each other.

When I finally got back to London, I walked into a flat to pick up a girlfriend, and there was my old South African buddy in the same room, taking another girl out. Small world.

Then I went to Venice, Rome, over to Monaco, and the rest of France on the way to Spain where I was going to spend the winter and write the great Canadian novel. I found a little inn outside Málaga owned by a Dutchman who couldn’t speak English. One night he came to me, pointed at the sky, and started to bark. I couldn’t figure out why he was barking until he got through to me that the Soviets had just launched Sputnik with a dog in it.

The great Canadian novel not complete, I headed north for London. I came out of sleepy Spain into the first French town where it was filled with crazy French drivers. A guy zoomed out of a side street and hit me. I went up in the air and came down on top of the scooter.

Luckily, I didn’t come down in front of it as I would have been killed. I woke up in the hospital, not being able to speak a word of French. None of the staff in this small town in this small hospital could speak English. They had seized my wallet and my passport while trying to figure out what to do with me.

One day a man walked into my room. He said in English, “I fought with Canadian troops in Korea and they were good guys. I saw the picture of your wrecked scooter on the front page of the paper. What can I do for you?”

His name was Guy Chaumont. He had been an officer in the French Army and had just won the Legion of Honour (the French version of our Victoria Cross). Guy explained that because of this honour he had the authority to deal with all sorts of officials and solve my problems. He got my scooter fixed, bullied the hospital authorities so I didn’t have to pay, and took me home to recuperate with his wife, who was an American.

When I got to Paris, I stayed with a couple of girls from Vancouver — Carol Gregory and a friend. I was down to $10 and went to American Express to get it changed. As I walked along, a guy kept following me and whispered, “Money change, money change.” These wide boys, of course, hung around American Express, since they knew that was where the dumb tourists were going to be.

At that time, as in Poland, French currency was at an artificial rate, and this guy was offering me a much better deal. He said, “Follow me.” We walked and walked through alleys and around corners and came to a deserted building. He arranged a deal, and I tried to offer him my money, but the guy said, “No, no. Wait here.”

He went away for five to ten minutes, then returned with a big thick envelope that looked to be about the right size for the money I was to receive. After he handed it to me, I gave him my money, then he turned and ran off. I opened my envelope, and it was filled with newsprint. I sat on the curb and cried.

A policeman came along and asked what was the matter. I explained. He shook his head, shrugged, and walked away. Another dumb tourist fleeced outside American Express. I borrowed enough money off Carol to get me across the channel to England and arrived at the home of old friends Patricia and Tony Prosser with one cup of gas left in the Vespa.