Читать книгу Boy from Nowhere - Allan Fotheringham - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеLondon Town

I couldn’t get a journalism job in London but heard they were always short of substitute teachers in the east end of the city. The east end was slums. Full of poverty and crime.

Going out there, I found that the teachers gathered down the street some distance from the school and walked in together for safety. Apparently, if you went in alone across the schoolyard, the kids supposedly playing pickup soccer would aim the ball at you, occasionally accompanying it with rocks.

I was shifted around from class to class. One day in the teachers’ room, completely confused, I asked where I had to go for my next class. A gnarled old senior teacher said to me, “Stay here, man. This is the safest room we’ve got.” The school had wire mesh on all the windows to protect everyone from the rocks and debris the kids hurled. I wasn’t a success as a substitute teacher.

Then I discovered there was a small paper on Fleet Street called Canada News. It was owned by Roy Thomson’s empire and was put out for the benefit of the Canadian troops on bases in Germany. So cheap was the operation that it relied on dupes of Canadian Press copy mailed over from Canada.

We would edit the copy and ship it up to the paper in Edinburgh, which Thomson owned. It was printed there, sent back, and then dispatched to Germany. This process took so long that the troops got the Grey Cup results just about when the baseball season opened.

Three women worked in the office. They told me that the previous editor, who was from Victoria, was a very morose man, as anyone working on Thomson wages would be. One Monday morning he didn’t appear at work. Tuesday he didn’t show up. Wednesday he didn’t show up. By this time, they detected a funny smell coming from an unused closet at the back of the office.

They opened the door and found the man, who had hanged himself. I always waited in glee for the first time I ever ran into Ken Thomson, son of Lord Thomson, and I would say, “Oh, Mr. Thomson, we have a mutual family friend.”

I never thought that years later I would meet at Rosedale cocktail parties a now-aging Ken Thomson who, in fact, inherited his father’s peerage but never once went to the House of Lords and declined to use the title that was his. He told me he was a great fan of my column, which appeared in the Globe and Mail, one of his papers.

Eventually, I found myself living in a basement flat with five Australians. One was an architect, another was an engineer named Vaughan Dobbins, a third was journalist Dick Conigrave, and the others were always out of work. It was a terrible place when in the winter the wallpaper was soaked in water.

The first Saturday night I was there, as the lads prepared to head out to the pub, the first one took a bath in the only tub. When he got out, he yelled, “Next!” To my astonishment, the next Aussie climbed into the same water. When he got out, a third guy got in. That was how much hot water the flat had.

Some months later Elliott Leyton, a friend from Vancouver, arrived in need of a free bed. When Saturday night arrived, I casually climbed into filthy, cooling water and beckoned him to follow. He glared at me as if I had lost my mind, and I realized I had adapted to the circumstances.

Elliott is now a professor at Memorial University in Newfoundland, is a world-renowned expert on serial killers, and is quoted in newspapers around the globe.

Aussies are a different breed. It’s a known historical fact that Britain, attempting to populate the far-off island colony, sent English convicts to settle in Australia. So, after a few pints at week’s end in the local pub, I used to say to the Aussie blokes, “You guys come from the worst criminals in England.”

The Aussies replied, “No, every one of our ancestors were individually chosen by the finest judges of England!”

One of their rituals was that every Sunday they would open the fridge, collect the leftovers, chop them up, and whip them with eggs. The result was what we called a “meadow muffin,” which went down well with beer. Decades later I made the same thing for my children and their spouses. They sat there politely and ate the disgusting dish that I was so proud of.

In time I got a job on the North American desk at Reuters in the most prestigious building on Fleet Street. There were six of us, and our total job was to take the wire copy coming in from around the world and change the word lorry to the word truck and the word bonnet (on a car) to hood, which is what it was called across the ocean. The work wasn’t exactly mind-expanding.

All of this was in the 1950s when every home in London burned coal as fuel. When the word smog was invented by Time, meaning smoke mixed with fog. In the winter in London it got so bad that elderly people with lung problems died by the score. The Reuters newsroom was fifty yards long, and sometimes at night we couldn’t see the other end of the place.

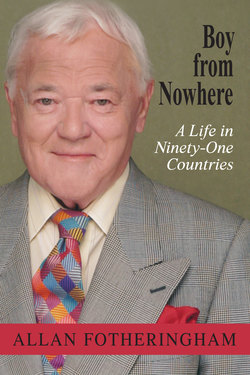

We scraped together enough money to get tuxedo rentals for Vaughan Dobbins’s London marriage in 1958. That’s me in the foreground on the far left.

One night I was doing a rewrite about Prince Charles and yelled over my shoulder, “How old is Charles?”

I heard this voice from an American whose name was Ed Fitzgerald, who said, “He was born at 9:14 p.m. on Sunday, November 14, 1948.”

“How do you know that?” I asked.

“I’ll tell you a little story. I was bureau chief at United Press International in London. As you can imagine, with the birth of a future king imminent, there was a ferocious race between the different wire services to get the news first to all of the papers in the United States.

“So I came up with a brilliant plan. We would write, waiting for the birth, two stories. One would say, ‘Queen Elizabeth tonight gave birth to a boy.’ Followed by all of the attended drivel. The second story would say, ‘Queen Elizabeth gave birth to a girl.’ With all of the usual details of what that would mean in the royal line.

“We had an attendant, the usual dumb Englishman who transmitted the copy to New York. There were two keys that sat before him. All he had to do when we got the word from the attendant we had standing outside Buckingham Palace was to push either the boy key or the girl key.

“One of his buddies, on his coffee break, came over to gossip with him and rested his elbow over — guess what? The girl key that went off to New York and three hundred newspapers. That’s why I’m no longer bureau chief of United Press International.”

Because of the Australians, I met at a party one night a seventeen-year-old girl called Leonie Leahy, whom one of the guys had met on the ship from Australia to England. She was a dancer and immediately got a job in the chorus of My Fair Lady, the biggest musical ever to hit London.

The original stage-door Johnnie, I waited at the outside theatre door after seeing My Fair Lady thirty-seven times and took her home on the back seat of my Vespa. She was the second strongest Catholic in the world after the pope.

We went to cast parties where I met Rex Harrison and his lady, Kay Kendall, who tragically died young of cancer. Leonie ended up as the prima ballerina of the Oslo State Opera in Norway.

One day at a party where all of the Canadians and the Aussies got into the brown ale, Jerry Lecovin, a guy I’d gone to UBC with, arrived. He was a lawyer I’d never met personally but had seen many times in the student reviews where he did a great imitation of Groucho Marx. Jerry explained at the party that he had this great idea to buy a Volkswagen and go through Russia, this being 1959 when the Soviets allowed foreign tourists to bring their own vehicles into the country.

He needed two other guys to share the cost with him to make it viable. “Fotheringham,” Jerry said, “you know everybody. Find me two other guys.”

I quickly found Keith Powers, a crazy Canadian journalist from Thunder Bay. And they urged me to become the third. I said I couldn’t possibly because I’d been saving for three years to get back to Vancouver to get a real job.

Months went by and one morning, after Powers finished the all-night shift at Reuters, we met with Lecovin in a greasy spoon for breakfast. Lecovin said he was abandoning the idea because he couldn’t come up with a third person.

I sat there and suddenly thought to myself, I’m going back to Canada, and for the rest of my life whenever the words Soviet Union come up in the conversation, I’ll be saying, “Oh, I could have gone there once, you know.”

Common sense sank in and I said, “I’m a go.”

At the Finland–Soviet Union border we were all lined up in the customs shed with a pack of American businessmen. Off in the corner was a gang of large, fat, old Russian women, all dressed black to their ankles — and one beautiful young blonde.

They were the official Soviet Intourist guides who had to accompany each group. “Mr. Weinstein of Detroit,” an official called out, and he was assigned one of the oldies. It went on and on, the oldies gradually disappearing.

Powers, Lecovin, and I stood in wild anticipation. Surely, surely, we wouldn’t have the luck to get the blonde. Finally, the last fat old lady was dispatched and we were introduced to twenty-five-year-old Ella Dimitrieva, who would be our companion in the tiny Volkswagen for three whole weeks on the way to the Black Sea.

Lecovin’s plan was to get to Istanbul, turn left, and head back to Vancouver across India and Burma, while Powers and I would get back to our jobs in London on my Vespa scooter, which I had shipped from Copenhagen to Athens.

Ella as an eight-year-old child had been through the siege of Leningrad and had been so weak she couldn’t get out of bed, her sole ration being one raw potato. The streets were so clogged with corpses that the survivors were too weak to carry them away. As we drove to Moscow, Karkhov, and Kiev, we took her dancing at night in the best hotels. She suddenly discovered lipstick and somehow acquired silk stockings.

Alas, all was not well with Lecovin. The guy I’d seen so funny on the stage at UBC turned out to be mean, a cheapskate who tried to cheat farmers when they sold us gas. He was completely humourless in person, which was tough when you were three weeks in a Volkswagen with four people.

The original plan was to drive through Romania and Bulgaria on the way to Istanbul. But the famed Soviet bureaucracy came into play. They gave us a visa to Bulgaria, but not to Romania. We couldn’t get to Bulgaria without crossing Romania. So we had to take a ship from Kiev to Odessa on the Black Sea.

First they told us there was no road between the large city of Kiev and the large city of Odessa, which was laughable, of course. When we laughed at them, they then said we couldn’t drive ourselves because of military reasons and they would supply us with a driver while we took the train there. We laughed that one off. I should add here that Powers and I had this brilliant idea of paying for the trip by taking pictures of every pretty Russian girl we saw and selling them to Playboy as a “Girls Of Russia” feature.

The final night in Odessa, overlooking the sea from a beautiful restaurant, we had dinner and fond words for Ella. Much wine, much laughs, and she took us down to the dock, kissed us all goodbye, and then turned us over to the police, who seized all of our photographs.

Lecovin, while Powers and I were dallying with Ella, had gone in first, and they had seized his camera. Instead of coming back and warning us, he scuttled aboard the ship to save himself. Powers and I insisted we weren’t going to budge until we got our cameras back.

At first they claimed they had a photo lab and would process the pictures there. Stubbornly, we waited, knowing that was nonsense, and then they admitted it wasn’t true but they were keeping the cameras. We said we weren’t getting on the ship until we got our cameras back. They then came to us and said the ship was leaving at 6:00 a.m. and if we didn’t board we would be in Russia with an expired visa.

We got onboard and didn’t speak to Lecovin, who had betrayed us for his own safety, for the three days it took the ship to stop in Romania and Bulgaria before reaching Istanbul. In Istanbul Lecovin turned left and we turned right. Powers and I picked up my Vespa in Athens and went back to London.

After returning to Vancouver, I wrote about the experience in my column, naming names. Lecovin avoided me for years.

Upon my return to London, I worked for a while at Reuters. But since I had used up all of the money intended for my flight to Vancouver on the trip to Russia and knowing it was time to return to Canada, my parents sent me cash for the airfare home.