Читать книгу Plot 29: A Memoir: LONGLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD AND WELLCOME BOOK PRIZE - Allan Jenkins, Allan Jenkins - Страница 11

June

ОглавлениеBy God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

Seamus Heaney, Digging

It is the month of early visits, of waking before 5am when the plot calls. The time of growth and hazel wigwams. Time to be concerned about seed. I lie awake – or sit at work – imagining the tender seedlings at the mercy of wind, rain, sun, slugs. Will they make it through infancy? With my help, maybe.

By 6am I am at the allotment, the air soft, the light too, the robin, maybe the fox, my only companions. The baby beans, only two leaves tall, are vulnerable now. Will they make it past the snails lying in wait like bullies? Within two weeks they will be free, snaking up hazel poles in a speeded-up film. Next month they’ll be two metres high, stems entwined, feeling for the next stick like rock climbers on a difficult face. Flowers will start to grow, pods begin to form. But for now I stand on the sidelines, a parent on sports day, calling urgent encouragement. Soon, like kids, they will be old enough to fend for themselves but for now at least I am here, not so much to do anything – the bed is hoed, weeded, pretty pristine – but as a friend, odd as this sounds, so they know they are not alone.

I learned, I think, to love from seed, much as other kids had puppies, kittens, fluffy toys. But it was the hopeful helplessness of seed that called, something vulnerable to care for. The urge to protect, to be there, was strong, like I couldn’t be for my brother Christopher when I left him alone in the children’s home; for my sister Lesley, out of harm’s way, I thought, with her dad, or Caron, whom my mother would abandon while she searched for new men, new sex, excitement.

SATURDAY 6AM. Sunlight has not yet hit the plot. Bill is sleeping less well since his wife died, so he comes here to kill time until Costa Coffee opens at 8am and he meets with his fellow insomniacs. His is the tidiest plot, manicured almost, everything neat in formal rows, plants perfectly spaced, celery blanching in brown paper, runner beans climbing up curly wire, blackcurrant bushes shrouded by nets. His seedlings are grown at home and transplanted into regimented rills. It wouldn’t work for me. I obsessively grow from seed in situ, needing the magical moment when an anxious scan along a row is rewarded by broken soil, a tiny stem breaking through like a baby turtle released from the egg before its dash to the sea. It has been two weeks since I have been here, and the salads have overgrown. Rows of rocket flowers shaped like ships’ propellers, land cress crowned with yellow spikes. The beans are under siege from slugs. Many inch-high stems are decimated, stunted, the baby-turtle equivalent of gulls swooping yards from the shore. Some have been simply obliterated. There is a sappy, fast growth to much of the plant life, perfect for predatory snails. Something has stripped a broad bean pod, though there are still many left. I walk through dew-soaked leaves and throw a few slugs over the wall. I will return later to pull much of the salad and let light in on the denser growth but the afternoon plan is to clear more of Mary’s beds.

Plot 29 belongs to Mary Wood, who has shared it with my friend Howard Sooley and me since 2009, when Don, her husband, died. Not because she couldn’t cope with the space (she is a gifted gardener) but because it produces more food, she says, than she can eat. Mary is poorly at the moment. As her energy levels have dropped, the weeds, the wild, have pressed in, strangling the plot. I am here to clear her green manure. Narcotised bees are everywhere, seemingly overdosing on nectar. They fall stoned to the soil as I clear. Sycamore seedlings infest the bed, the overwintered chard is blown, a metre tall, menacing nettles taller. I work quickly, scything, clearing, restoring order. It feels important now that Mary’s plot doesn’t also succumb to attack.

I clear the bed, transplanting a couple of short rows of six-inch chards, sowing another of beetroot seed. I return later to talk to her. She is here less than in previous years but sunshine and a need to replant sweet peas has drawn her out. She has a chair on the allotment now, and sits more often. We talk about what she wants to grow this year, and where. I cut pea sticks for a row at the bottom of the bed. With little time to work our part of the plot, I sow nasturtium on the border.

My gardening life, in some ways my life, begins with this simple seed. Most of my memories start at the age of five, perhaps because there are photos from then, perhaps because almost everything before then was chaos to be peeled away later in the therapist’s chair and in talks with members of my ‘birth family’ (a sly phrase we have been taught to say instead of ‘real’), when I found them many years later. Perhaps simply because that is where safety starts. With Lilian and Dudley Drabble.

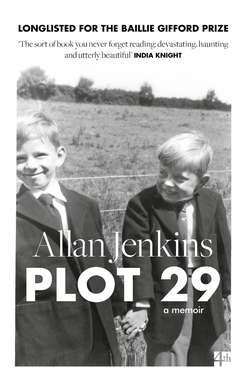

There is a photo of my brother Christopher and me with Lilian as young boys. Christopher is lopsidedly smiling, proudly holding his new ginger kitten. It almost matches his hair. Lilian is crouched with Tonka, her Siamese cat. I have my arm around her, looking a little warily into the camera. The boys’ clothes are comically big. Not ‘you will grow into them’ big, but clothes bought while the intended children aren’t (have never been) there. We were small for our age. But these are new clothes for a new life in our new home with our new family.

Lilian and Dudley married in their forties. They met when she nursed his dying father. Too old to have children, they at first looked to adopt a baby girl but were denied, perhaps because of age. It was a loss Lilian would always feel. She wanted someone all her own, someone she could mould and make, who would wear dresses. There was somehow always a sadness we couldn’t assuage.

Meanwhile, the Drabbles offered respite to ‘damaged’ children at their picture-postcard post office on Dartmoor. Christopher and I spent a weekend there, shooting bows and arrows, learning to say please and thank you (we were ‘guttural’ Dudley would later delight in telling me).

Plymouth children’s homes were feral then. Snarling packs sniffing out fears, tears, blood. Not always only the boys.

We learned a lesson about caste here. First, of course, there were the Brahmins: the ‘Famous Five’ families with their normal ‘mum and dad’ (small words still able, occasionally, to conjure black holes of unhappiness).

The adopted were the ‘chosen ones’, mostly children of the over-fertile underclass taken in by the infertile middle class. The unworthy become worthy, if you will; a shift in status almost impossible to imagine – a parole from purgatory.

Foster families were holding pens – a sifting, shifting, near-family life spent waiting. Here we would practise being appreciative and loving, living under the fear or hope or threat of the knock on the door. A dread visit from the social worker, who might pass you along, around or back.

At the bottom, of course, the untouchable unlovables. The broken kids in care with the mark of Cain, the ones no one wants. My brother Christopher.

Residential care operated like dogs’ homes – abandoned pets kept penned until someone, anyone, might take them. I remember days my hair was specially brushed. I was told to smile, because new parents might see me, heal me, love me, take me off the city’s hands. There is a skill, you see, to being lovable: a fluffy, undamaged Disney dog, eager to engage, with a wagging tail. Christopher couldn’t or wouldn’t learn. People were nervous of his nervous tic. His face twitched, his mouth twisted. He was stunted. The runt of the litter with perhaps a subtle hint of trouble to come. Though appearances can be deceptive.

I was rehomed but would keen for Christopher until they returned me to the pack, just another ungrateful, undeserving boy. Until the days of Lilian and Dudley Drabble, their house on a Devon river, a kitten, a cat and a magic packet of nasturtium seed.

I grow it still, this unruly, gaudy flower. It is prone to infestation, the first to fall over in the frost, but my gardening is saturated in emotional memories, as with music and love. So I sow nasturtiums because they are tangled up like bindweed with thoughts of the boy I was, the boy I became, the brother I lost, perhaps the father I’ll never know. And I sow runner beans for Mary because Don, her late husband, grew them. Mary also offered me a home, a place to grow when I didn’t have one. So we talk about peas and radishes, about the rocket and lettuce I will sow when she starts treatment.

Later in the week, I meet with Howard to stir biodynamic cow manure by hand in water for an hour. From the beginning of working the allotment we chose to work this way, inspired by Jane Scotter of Fern Verrow farm in Herefordshire, the finest grower we know. In most areas of my life I carefully calculate risk and reward, working within tight budgets and remits. Here, it is different; organic plants grow, foxes are free, flowers spread, children run around. As an adolescent I was banned from confirmation class for being unable to buy into the church, the resurrection and miracles but I have since learned to suspend my disbelief. A journalist, I stop asking questions and try to listen. We follow a lunar planting calendar and avoid invasive pest control. We believe our crops last longer, taste better – the rocket is hotter, the beetroot sweeter, the sorrel more sour. It works for us. We feel more connected to the soil. It suits us and the space.

There is something deeply meditative about the stirring process, encouraging you to focus, to sit still for an hour at dusk or dawn, whatever the weather. Howard has to leave early, so I also spray the mix around Mary’s plot.

The next morning I am at the allotment early to sow rows for Mary and me. I am keen to catch up. I was exiled from the plot with a fractured ankle for four months over the winter. There was a disconnect from the soil with which my wellbeing is intricately entwined. Suddenly, catastrophically, walking and gardening, the twin chemical-free medications I have built into my life, were shattered along with my bones. I am rebuilding this connection now, but it is slow. I am back walking along the canal to work, over the heath or along beaches, but I have missed the overwinter planting that greens the brown soil that surrounds us. I have a thought the plot is sulking, like a cat or child that has been left alone too long. The three bean structures I have built on the two plots are prone to attack. The urge for organic slug pellets is strong.

Later, an allotment neighbour comes to talk over bad news. William, the kindly chairman of the association, has been found dead in his flat. I have always been grateful to him for the gentle way he defused tension between the plot holders and the helpers. William had been forced to leave his native South Africa when his student activism had come to the attention of the Afrikaans authorities. In London, he had written and directed successful plays, he had been a book reviewer, pictures showed he had been beautiful, but the William I knew was a shy, bespectacled man who grew tulips and peonies, and at whose plot I always stopped to talk about gardening, the weather and the problems with sharing sheds.

The slugs may be winning their battle with the climbing beans. The early salads have bolted. The garlic and shallots that had looked green and healthy only a few days ago have succumbed to papery rust and need to be pulled. The wild Tuscan calendula has spread like duckweed and is smothering other plants. For my first time in June, the plot is in need of a reboot. The living carpet that normally covers the soil is threadbare and worn. A couple of weeks before midsummer I start again. It is hard sometimes not to think that your garden says something about you, the green fingers you hope you have, your innate ability (or inability) to nurture. Hard not to feel good about yourself when the plot thrives, or like a failure when it falls. The fault must be yours and not the seed, the weather or blight on the site.

Without early success at growing as a kid, I guess, I might not be doing it now. It was the first time as a child I thought I might be gifted at something. In south Devon, Dudley gave Christopher and me two pocket-sized patches of garden and two packets of seed. Christopher had African marigolds (tagetes): bright orange, cheery, the stuff of temple garlands. I was handed nasturtium flowers: chaotic cascades of reds, oranges and yellows (Dad liked bright colours), which soon overflowed. Caper-shaped seed heads would dry in the sun. I was amazed (still am) that so much life can come from a small packet. Later my nasturtiums would fall prey to black fly, a nightmare infestation sucking sugary life. Lilian showed me how to spray leaves and stems with soapy water, holding back the devastation until frost would turn their green into limp, ghostly grey; a silvery sheen of dew signalling the end. I would pull them, shake out seed for next year (though the self-seeding was always enough) and throw the lifeless bodies on the compost pile to rot down and turn into soil. This idea of nature’s renewal fascinated me. I was in love.

For the first few years at the allotment I helped with a primary school’s gardening club, where children from five to 11 learned to grow. Kids who might be having trouble settling in class worked together during Friday lunchtimes. Seedlings grown in the greenhouse were replanted in raised beds in the playground. I would host their visits to the site. Branch Hill, where we are, is like a Victorian secret garden: gated, only just domesticated, sheltered by tall trees. We would give the children sunflower seeds and watch them stand, stunned, as the plants grew faster than them. We would eat peas from the pod and taste herbs. One memory sticks: watching the blossoming of a Somali-born girl. At first head down and standing shyly at the back of the group, she began to join in, to enquire about sorrel, lovage and other flavours unfamiliar to her. By the end of the year, impatient at the gate, she would rush to ask for magic nasturtium, her favourite ‘spicy flower’.

1960. Christopher is morphing from an undersized child into a fast-growing boy. The nervous reserve is fading too. He is talking more often, more excitedly. Always out with his fishing rod or digging for bait. I don’t have the stomach for threading anxious ragworm on to a hook. We never eat fish he has caught. He never brings it home. He doesn’t like fish for tea anyway. He is a meat and potato boy. His favourite: Heinz spaghetti on toast. He gradually drifts towards the village. He can more clearly hear its call: the dog whistle of other kids. I see them on the hills, on the horizon, like spotting a fox. Within a few years he is a natural athlete, gifted at sport. He is better at being a boy than me. He is more natural. Cars and bikes, cricket and football; later, beer with bigger lads. Soon after we arrive, Dudley builds us a push cart. He paints it bright yellow and blue. Chris’s freckled face brightens as we tear down the hill behind the house, laughing as we hurtle towards the river, skewing across the tidal road, the wooden handbrake screaming as we mostly avoid the mud. He is gradually healing from his fear. He is gaining height and weight. After a few years of living in Aveton Gifford he is an annoying inch taller than me.

I am back at the plot and the snails are still rampant on Mary’s patch. I am not sure why. I have cleared a lot of weed and there are few secret places left to hide. Maybe it is just their year. I have sown and re-sown peas and beans but they cull the baby shoots almost every time. Skeletal seedlings lie at the base of the poles. It’s a bean battlefield. I succumb, finally, to buying organic pellets. The biodynamic thought-police would frown but I cannot have thriving crops while Mary’s wigwam is bare. I restock French beans (in three colours: yellow, green and blue) and go up one evening after work. The site is empty, smelling of hay and English summer. Clumps of calendula almost shine through the early gloom. I sow more beans at the base of Mary’s poles and uncover the first stirrings of last week’s seed, sprouts curled like dormice. I replenish the pea sticks and scatter protective pellets. Time is starting to run out. We are a week from the solstice and I won’t be here to help. I am heading to the other magical piece of land in my life, a summerhouse plot on the East Jutland coast, where I plant mostly trees.

It is always odd leaving the allotment for any length of time. I feel as if I am abandoning it and it won’t understand. It is a recurring irrational feeling (a theme through my life like a name through seaside rock). But it is stronger now, reinforced by my enforced absence over the winter with broken bones.

The Danish plot is different. It is an echo of Devon. Coastal, even the wide stretch of shallow water and white sand is the same. Here the garden is larger, wilder, more isolated than in London – about 1,500 square metres of sandy loam 300 metres from the sea and a few kilometres from where my 90-year-old Danish mother-in-law lives. Close enough for her to cycle.

We have had this house and land for 10 years now. It is maybe my safest place.

Of course, there are many echoes of Dudley, of our house, Herons Reach, of home. They are here in the climate, in the light, in the anxious dragonflies, the blue butterflies, in the flowers: pink campions in summer, pale primroses in spring – the same shy, unassuming flower I used to pick for Lilian on Mothering Sunday. Here in the finches and tits we feed, in the sudden arrival of migrating flocks that stop off to feast on the wild cherry trees, the red-berried rowan. Here in the orange-backed hares that lope through the meadow, the foxes and badgers that leave tracks in the snow. In the brambles that line the beach, conjuring comforting images of late-summer days, picking through hedges with Lilian, packing small churns with berries, my hands and face stained with juice. Perhaps most of all the memories are in making the blackberry and apple pies that Dudley adored with buttery Devon cream (Lilian was not a gifted cook but she could make a good pie). Yet the deepest Devon echoes are in the trees. Dudley loved to plant trees: poplar and laburnum to line the new drive to the house, Japanese cherry for the autumn-colouring leaf I liked to press between pages of my exercise book; apple (Cox’s Orange Pippin for eating, Bramley for cooking), Conference pears and Victoria plums. When I was about seven he planted 200 six-inch Christmas trees it was my job to look after, to trim the choking grass. This was my least favourite chore, worse even than raking the acres of endless lawn. The tiny trees were fiddly, with no hiding place if the shears skipped and a stem was severed. Christopher escaped this because he chopped too many trees. Smart like a fox, my brother.

Perhaps in honour of Dudley, though it is never as explicit as this implies, I grow mostly trees here on Ahl – a few old Danish varieties of apple and plum, three espalier pears, red and blackcurrant bushes, with pine, fir, larch, birch and beech. They are chosen to fit in with the area, a peninsula of old plantations with wooden summerhouses dotted through. When we first found the house, we had to cut down senile trees that surrounded the plot. We chopped them with the help of our neighbours, the same neighbours who gave up weekends to build a shed for the wood they helped saw and split for the stove; the same neighbours who light our morning fire in winter before we arrive. Solitude plus community, the constant I search for, the same as the allotment, an echo of a Devon village life that no longer exists and to which I never belonged.

As with the allotment, I lie wondering about the plot when I am not there, suffering the same wrench when I leave. I sow tulip bulbs in the border in winter with only a slight chance I will see them bloom. The appeal lies in knowing they are part of a dialogue with their surroundings. I am happy if my visits coincide with flowering but I don’t have to be here at the time. Finding the spent flowers, petals fallen, their colours faded, is enough. Like the allotment, it is the growing that is the thing. Although I take childish delight in seeing the larch shoot up, reach for the sky, I know I most likely won’t see it at its majestic best as a mature tree. But someone will, maybe a small boy as he swings on it or plays in the summer grass. In the meantime I mow, and occasionally remember Dudley carving lawn and meadow and orchard out of field and Devon hill, his beret on (like him, perhaps, a relic from wartime), his neatly trimmed military moustache (ditto), his tightly belted corduroy trousers, grass-green stains on his shoes, and I watch and wait.

I see the larch outstrip the three new birch while its sister tree picks up sunlight and shadow in the other corner. I watch the new, soft green shoots from the saplings bought from an ad in the local paper. I sometimes move the small trees around in the plot until they find their spot and settle. I watch the wild rugosa rose take and spread. The local authority has a love-hate relationship with the sprawling, fragrant flower banks that line the length of the beach, razing them to the ground every year. They are Russian, they say, though the beach has had the roses as long as anyone remembers. The Danes have a conflicted relationship with invasive outsiders, though I, of course, root for the rugosa.

I watch the shy redshanks flutter and feed on ants in the evening. The male calls his morning warning as I pass the bird box they return to every year (I turn left, walking the long way around the house so as not to upset them). I observe the spotted woodpecker train its fledgling in feeding while a tit craftily creeps up behind them in case they miss anything. I listen to the blackbirds as the male sings from the highest branch of the tallest birch and as pairs patrol the lawn, puffed up and important. With these too, I avoid the woodshed when they nest there, a nuisance on cooler Nordic mornings if I want to light a fire.

I admire the starburst of wildflowers on the south side of the house: one year a swooning bank of scarlet poppies, the next year ox-eye daisy, then nothing. I obsessively buy and scatter wild meadow seed to little or no effect. I plant new banks of beech to replace some of the seclusion lost when the tree surgeon ran rampant through the plot. I move the Reine Claude plum to see if it is happier in a slightly shadier spot. Mostly though I train my eye to see the small changes since my last visit: the jewel-coloured beetles, the frogs, the trefoil, the shy hepatica flower, as I lie in the dew for a closer look on my ritual morning walkabout. Everything here is geared towards spring and summer, to the new leaf that shuts out the neighbouring plots, pushes them away, electric green walls if you will, infested with teeming new life, the all-day dawn chorus.

SUNDAY MORNING, LATE JUNE. I am on the first bus, my travelling companions the domestic workers heading to Hampstead, to the larger London homes they clean and care for. I haven’t been here for a fortnight and am keen to see the allotment and if the emergency bean sowing has worked. I have missed this place. My heart lifts when I arrive. Mary’s bean poles have eager vines on every stick. Her summer plot is saved. OK, tap-rooted thistles are thriving, there is an explosion of weed, many of the peas and broad beans are blown and fallen over, some seed has failed to germinate, but nothing that can’t be fixed by a day or two of hand-hoeing. Suddenly, a flash of rust, a glimpse of white on a scurrying tail as a fox darts across my path. My first sighting this summer. A good omen. Maybe omens are a country-kid thing but maybe also the plot will forgive me for my broken leg and absence. I sow saved red tagetes seed and get to work. A break for breakfast at home, a couple of hours for Sunday papers and back to tidy the potatoes. They are close to cropping now. The chard is heavy-leafed and luxuriant. I hoe every row and re-stake the peas in a downpour. I like giving in to gardening in rain. It closes off the outside, focuses your attention. Just you and the job: a meditation of hand and hoe. A moment of connection. I tie the peas and think of a friend who mails me seed. I send him an eclectic collection, saved and shared from around the world, he sends me Basque peas and intense, small tomatoes because they speak of him and his region. The peas are to be picked young, and sometimes when I eat them I remember Ferran Adrià’s El Bulli, and I remember Lilian.

2011. It is one of the last nights before the closing of the best restaurant in the world. Dom Perignon has flown in 50 guests by private jet: serious wine investors, Silicon Valley billionaires, film stars, their boyfriends, another food writer and me. We are helicoptered into the beach like a scene from Apocalypse Now. We eat 50 small dishes – eggs fashioned from gorgonzola cheese, small, gamy squares of hare, sea cucumber filaments, rose petal wontons and peas. Excited conversation and Dom Perignon ’73 flow. I am sitting at a table of high-powered dignitaries when, deep into the meal, a wave hits me. The room and noise fade a little, a shard of emotion breaks free and I notice my face is wet. I am quietly crying. Ferran Adrià’s peas have burst in my mouth like memories. I’m no longer sitting opposite Roller Girl from Boogie Nights, I am aged maybe six, in shorts and stripy top, on the pink porch of our Devon house. Lilian is there with me, in her yellow patterned summer dress with blue butterfly-wing brooch, sitting, smiling, patiently podding peas into her dented aluminium colander. And as I pick up a pod and help her, I know this is what safety will forever taste like: garden peas freshly picked from the lap of your new mum.