Читать книгу Plot 29: A Memoir: LONGLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD AND WELLCOME BOOK PRIZE - Allan Jenkins, Allan Jenkins - Страница 12

July

ОглавлениеThe broad beans are almost gone now, just a half dozen or so spring-sown Crimson-Flowering from Mads McKeever at Brown Envelope Seed in Cork. I came across this old variety – and Brown Envelope – early in 2007 with the arrival of the Seed Ambassadors. Andrew Still and his wife Sarah are seed hunters from Oregon, where many obsessive plant breeders are based. Andrew’s passion is for kale, and the pair were on a European tour starting deep in Siberia and ending with Mads on the west coast of Ireland. With Andrew and Sarah came stories. They arrived at the plot on a cold winter morning with packages: from Tim Peters of Peace Seeds, breeder of Gulag Star, a winter salad cross between Russo-Siberian kales and mustards; our first Flashback Calendula. I learned that day of Trail of Tears beans, named from the winter of 1838 when Cherokee were forced from their farms in the Carolinas and marched to Oklahoma in the Indian Territory. First offered through the American Seed Savers Exchange in 1977 by a ‘Cherokee descendent, gardener, seed preservationist, circus owner, and dentist’, Dr John Wyche, the beans can now be shared and bought from heirloom growers. I save the seed and still grow the crops Andrew and Sarah gave us. This year, Trail of Tears have made their way on to a couple of Mary’s poles to supplement the beans that had been struggling to survive.

The pellets and sun have done their work, the wigwam will thrive this time. I weed around the base, careful not to disturb the geraniums Mary has planted there. Elsewhere, there are ominous signs of smothering bindweed breaking through, but Mary has been clearing another small winter bed. I thin out calendula now rampant on both parts of the plot, the flowers sitting brightly by this screen as I write in the early morning. It is glorious high summer, time to garden with a hat and with the sun on your back, time to harvest lettuces, peas and radishes for home, almost time to sow spinach. But the solstice passed a few weeks ago now, the days are warmer but the nights are a little longer. It’s time to begin to plan and plant for winter.

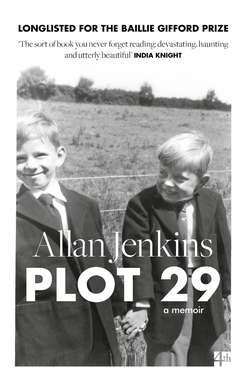

Summer for me is saturated in early memories of Herons Reach, the house on the riverbank that Lilian and Dudley bought to bring up the boys. When I talk of those days, my early life, it is often of ‘the boy’ (or boys) and what happened to him (or them). I rarely use me or we. It might be to do with confusion or creating a protective distance. I notice other people with a similar background do the same. It might be to do with shedding identity, like the ethereal adder skins I used to find in the Aveton Gifford churchyard. It might be about naming. Mum and Dad didn’t like the name Alan, so quickly chose to call me Peter, my middle name, instead. And after a probationary period – I must have passed a test – I was given Drabble (Christopher resisted and stubbornly stuck with Jenkins, a schism between us). Now that we were safe, they thought we could be safely separated.

Scared city child Alan Jenkins was fading, at least for now. Bright-eyed, blond-haired village boy Peter Drabble was cocooning, being born.

As we played, the house too was being expanded, refashioned and renamed. North Efford (north of the ford), a farm labourer’s cottage was metamorphosing into Herons Reach. An extension was added, light was let in, the exterior given a new coat of pink render; rust-red Virginia creeper was trained up its side. That long, happy summer, the first deeply etched into my memory, Dudley waved his phoenix wand, knocking through for French windows, buying the large field behind the house, laying in a drive, the foundations for a lawn, a croft. He planted more trees. Like me, the house was shrugging off its darker past. There was sweet strawberry jam being made in the kitchen, the sound of boys, a cricket bat on ball in the garden, plums and apples were coming in the orchard. Dudley was carving out a home fit for his new family.

While the work was done, we lived in a caravan. It was light, had a breakfast bar and drop-down beds, though we were never inside except to sleep. Christopher would play cricket or football, while I would climb trees and explore the river, catching eels and sticklebacks and putting them in jars until they died.

We had different hair, different eyes, a different smile. He had hazel eyes I almost envied, reddish hair I liked, freckles I wanted, though not the burning in the sun. He was slight while I was heavy, his grin was wider, though mine came more easily.

My favourite photo of Christopher is from that idyllic summer of ’59. He is sitting in the doorway of the caravan with a proud-looking Dudley holding him. Christopher is happy – his tic is slowly disappearing. He is being hugged. He is being loved.

The open smile would slowly disappear. His bright, tumbling chatter would go quiet. He would withdraw back into himself, if not quite yet.

JULY 4. We have fruit on all the tomato plants, about a dozen or so, growing in pots on the roof terrace. Ironic they are there, because it is through tomato seed I found Plot 29. It is July 2006, I am editor of a national newspaper Sunday magazine, juggling million-plus budgets, million-plus readership, 20-plus staff. My day is spent dealing with photographers, writers, agents, celebrities and fashion designers with delicate egos. But all I can think of is how my tomato seedlings are faring when the weather changes. How will they cope with the cold or heat? My next Observer Magazine cover can wait. I am haunted by helpless plants. For the first time in 20 years, my work has a rival. I feel as if I’m needed elsewhere.

I am not alone. There are a few of us on the magazine currently obsessed. We swap small plants and compare their size. We talk of little else.

I have had a roof terrace at home in Kentish Town for years now where I grow flowers and plants in pots. I am married to a modernist architect who likes clean lines, neat rows of seeding grasses and palms. Every year we compromise on a few geraniums – a hangover from my first teenage job in London at a Kensington garden centre. But the haphazard trays of tomatoes are becoming an issue. Where are they all going to go?

It may be only at work that my obsession is understood. The Observer Magazine tomato growers have become competitive. Someone brings their tall seedlings in to show off. We share tomato photographs. And then it hits me: we need a space to grow. Maybe we could sow together, write together, design together, work outside the office. There would be a different dynamic. No one would be the editor, we would create a utopian ideal. We would, I think, grow tomato plants in harmony, like the Diggers or a Sixties collective. I was getting ahead of myself.

We consider guerrilla gardening, transforming urban space. We contact councils to see if they have unused land on a housing estate that would benefit from a few flower and vegetable beds. We ask if there is an empty allotment we could take for a while. Then we find Mary’s sister, Hilary, Camden Council’s allotment officer, and Branch Hill comes into my life.

2006. Ruth is the tenant of Plot 30. She has waited 18 years for an allotment, until one came along when she wasn’t well. It is in north London, near where I live. Hilary says we can garden it for a year and hand it back as a working space. Ruth will hopefully be better by then.

We go to see it.

Ruth’s plot neighbours the one we garden now. My first allotment love, it is hard to make out at the start, not so much overgrown as swamped with weed. It falls quickly away down a steep slope, littered with bindweed, bushes, large abandoned lumps of concrete. This is allotment as waste land. My companions’ faces fall. Mine lights up. Here is territory I have long understood: a garden damsel in distress; beautiful, abandoned, like a rundown river cottage that needs work and a helping hand to express itself.

It starts well. Magazine staff give up weekends to dig. We are seeing ourselves in a different light: muddy, more than a little sweat. But there is too much to do. It will take too long. The weeds are endemic and we are digging out lumps of old buildings lurking malevolently underground. We unearth an Anderson bomb shelter complete with corrugated roof. It is too much to ask. It is their weekend, time to get away from work. Within a few weeks I am on my own, with the rain, the buried bricks, the wire and broken glass for company. Enter Howard and Don and Mary.

I’d first hired Howard to take photographs for Monty Don’s gardening column in the magazine and had loved his work since seeing his book with Derek Jarman on the Prospect Cottage garden in Dungeness. This was austere, artful planting in almost savage harmony with its situation. Howard’s quiet pictures of Jarman, of driftwood and detail, had changed everything for me about how to see space.

Jarman captures him in the book when he writes: ‘Howard Sooley is a giraffe, a giraffe that has stared a long time at a photo of Virginia Woolf; he possesses the calm and sweetness of that miraculous beast.’ From out of this calm – and companionship – together we would conjure our first miraculous plot and go on to make more.

1960. Christopher is obsessed with forming clubs. We have homemade badges, drawn and coloured on card, attached with safety pins. Mum is concerned about the holes in our shirts and jumpers. Our badges are usually round, sometimes shaped like shields. There are arcane rules. He is always the leader. I am the only other member. We are always a secret society because other boys are immune. We never ask girls. We make dens as meeting places. I swear loyalty to the club and Christopher. I am soon replaced by cricket.

SATURDAY JULY 11, 6AM. Under siege. The midges that hang around the pond and plot in the summer evening and early morning are attacking me. I am intent on clearing space for new growth, letting in light and air. It is already monsoony humid, threatening rain. I don’t much notice the midges at first, batting them away absentmindedly, irritated by the odd bite as they penetrate gaps on my shirt sleeves, the pale flash of flesh as I bend. I clear the last of the broad beans, battered by slugs. I pull invading calendula, picking through it for cut flowers for the kitchen table, leaving the vivid orange bloom I haven’t the heart to take. I thin through new-sown salad for lunch. There is much still to do when my face and arms begin to itch uncontrollably, like a child with chicken pox. While I have been working, the bugs have been feasting. I urgently need something to stop the swelling now pressing on one eye, and the raging scratching. I retire from the skirmish, stopping to grab leaves, beans and flowers, and flee.

Later, hopped on antihistamine, smothered in cortisone cream and disfigured with a leer, I return. Howard joins me. We need to sow. The twin pea beds at the bottom of both plots are failing, so we will supplement them with low-growing bush beans. It may be our last chance to sow them this year. We pull the flowering coriander and hang it on a wigwam to dry. I brought the original packet back from Brazil. It is intensely spicy – a local strain, I think. We save the seed for later. I clear another bed for wintering chicories. At the last minute I rip out the top bed too and re-sow with a black bean from Brown Envelope. The crinkled peas should have been picked while we were away. We eat a few from the pod and divide the rest. As the light dips and Howard gets bitten, we finish. In the three hours we have been here we have hardly spoken. The few words exchanged are about the benefits or not of getting a wheelbarrow and which beans are for where. Conversation picks up on the walk home down the hill.

1961. Almost as soon as Christopher and I are reunited we begin to grow apart. Nurture acing nature, if not just yet. He holds on fast to his history and name (though why this decision is his I don’t understand; it should never have been). I pack myself away in search of something safer, smarter, more versatile. Like a Christmas cowboy suit, like dressing up. My identity is broken, soon it will be time to try on Peter Drabble; from underclass to middle class, like the jacket in the first photograph that didn’t yet fit. I often imagine now how my brother’s life would have played out if Lilian and Dudley had called him Christopher Drabble. In my head he is smiling, happily married, with many dogs and kids, maybe managing an arable farm in Canada. His life would have had more choices.

Herons Reach is on the Stakes Road across the mud flats, half a mile from school if the tide is out, a mile if it is in. I love messing on the river on my own, while Christopher loves the village. He is bigger now, brilliant at head-butting me, but I can feel his fragility. Sense the uncertainty. See it when no one else is interested. He will come to rely on his fists. I will rely on my wits.

The change will come between us often. Rural Devon in the Sixties is still remote. A place where brothers have the same names, the same features, the same interests. We are different, and difference is difficult.

Other boys too are to be discouraged, at least at home. In our first year there is a birthday party but this is to be the last. Lilian doesn’t like boys or parties in her house – too noisy, too messy, too muddy, too hard-edged. Softness for me is to be found in other kids’ homes, a warmer welcome with a tender touch. Boys don’t much come around again, not even for Christopher and he collects friends like I collect stamps. He starts spending his days at the farm next door, walking the fields, helping call in the cows, bringing home milk and mud. The farmer is handsome, young, in his twenties, a bachelor, though this thought has only struck me now. I prefer to stick closer to home, closer to Lilian and Dudley, watching as she pares the runner beans he grows into neat piles of wafer-thin green. Food is always simple, almost always freshly grown. For Dudley, as for Mary’s husband Don, runner beans signal English summer.

SUMMER 2007. Ruth’s allotment is slowly taking shape. Howard and I have spent weeks up to our knees, thighs sometimes, trenching out bricks and glass, wire and wood, tree stumps and concrete posts, while Don looks approvingly on. Mary leaves us small bags of salad as encouragement. One day, the allotment association steps in. They hire a skip and I arrive mid-morning to find a fireman’s chain of wheelbarrows to run the rubble up. It seems everyone is here to help.

Sarah turns up from the advertising department of the Guardian where I work. Who knew wellingtons came with high heels? She helps me spread five tonnes of topsoil we’ve brought in to slow the slope. She learns to kill slugs and snails. She drives 300 miles with me to pick up a lorry load of cow manure. ‘Horses’ energy is too fast for vegetables but fine for flowers, you need cow’, was the opaque advice from Jane Scotter. The manure is a gift from a farmer who had answered a plea put out into the biodynamic community. It’s harder than you think to find organic cow muck in London. We drive back delicately in our hired, loaded-down flat-back truck (we have been a bit vague about what we want it for, failing to mention manure). We are barely making it up the hills, laughing, almost choking, in a heavy fug of farmyard.

The slope is tamed now, the soil is fed. We are ready to grow.

The Danish agricultural museum has sent us ‘lost’ seed, including Tagetes Ildkonge (for Christopher), the deepest-red, most velvety marigolds we have ever seen. Sarah and I plant a large bed of perpetual spinach. We have a wigwam of fragrant sweet peas and another of purple-podded Trail of Tears. The tagetes grow to a thick hedge. We have herbs, fennel, flowers, beetroot, carrots, kale, mustards, green manure. I set a national competition for school gardening clubs to design a scarecrow and have the magazine fashion team build and dress the winner. Soon a six-foot scarlet pirate, complete with eye-patch, hat and silvery sword, guards against the resident pigeons. They ignore him. We plant an apple tree, a plum tree, gooseberry and currant bushes – just like Dad. Everything we sow grows lush like rainforest, as though its energy had been imprisoned and is now unleashed. The allotment is happy and so are we, but I can’t bear to thin and throw the weakest tomatoes – maybe I identify with their need, preferring to give them more light and food and love. Soon we have 20 plants, tall and fruiting in the sunniest spot at the top of the plot. We don’t know blight is endemic on the site and that nurturing rain also spreads disease. Their leaves start to brown and buckle. The tomatoes too. Seedlings I have nursed from birth are sickening and dying, and there is nothing I can do. Throughout the site, tomato plants are failing. The weakest die first, of course, their fruits blistered, their stems and leaves discoloured. Seasoned allotment holders strip the leaves and spray them, like a field hospital for failing plants. Still they fail. Like plague before penicillin. In the end we pull them all and cart their corpses to the green bin by the gate. No compost renewal now. A gardening lesson in love and loss. But one I am reluctant to learn.

SUMMER 1973. My first garden in London is in Elgin Avenue, a street of squats near Notting Hill Gate. I am 19, working for a garden centre in Kensington, selling window-box flowers to posh west London ladies. Here, it seems, everyone buys their gardens ready made, no time to wait. This is gardening as competitive sport. I have become skilled at persuading neighbours to upgrade over each other. If one has bought red geraniums and a three-foot window box in terracotta, I’ll sell next door a three-and-a-half-foot in stone and with better, bigger flowers. No one grows from seed. There is a lot of waste. This is new to me. I start carting home pots of dried-out azalea rescued from the bins. Soon I have buckets of rehydrating bushes inside and outside the flat, front and back. I nurture my waifs back to life. As the garden fills up, I start planting out the rest. The speed freaks don’t much mind as long as they don’t have to water. I spread down the street as fast as the dealers spread up. We have azaleas, geraniums, pelargoniums, magnolia, a bay tree slightly bent out of shape. There should be an award for the best-dressed street of squats.

JULY 17. The temperature has been in the high twenties for the past three days and I have promised Mary I’ll water. She is taking a break in Cornwall and I want the plot to look well in time for her return. Howard and I head up before breakfast. I love the light at this time, fruit trees and bushes backlit by the low early sun. Our neighbour Jeffrey is an American banker with a passion for English cottage gardens. His fennel and hollyhocks are two metres tall. Bees stream from the next-door hives like Star Wars fighter squadrons. A fledgling robin, head cocked, watches us. Red amaranth and bull’s blood chard stand in contrast to the other, younger lime-green leaves. All is right in allotment world. Howard waters while I take more calendula, mildew at its base a warning signal of autumn. Time for the borders to breathe, time for beans. Of course we have too many (the seed finally pulled though). Feeler vines outstretch like a drowning man’s hand. Howard is buttoned up against bugs but still they get through. The anxious scratching starts.

SEPTEMBER 1959. The village school test for TB has alarmed Mum and Dad and me. My left arm is very swollen, with red streaks running down. And the doctor thinks I am ‘rickety’. Christopher is OK, which only means more mystery. Where was I? Where was he? The first clue we maybe hadn’t always been together. But why our amnesia?

Rickets. A Dickensian world away from the family life the Drabbles have been building. No vitamin D and now I am touched by TB. Capital letters writ large of lack of care. Where was family, where was safety, where was my other mum? It had been beaten into us at the home, this cross we carry. We are either unlovable or the cursed brood of an unloving mother. Either way, we need to be quarantined from the herd. Mums are meant to be like Mary, a loving Christian icon clutching her baby to her breast.

For the next 10 years I have an annual X-ray, looking for lesions. My sunken chest pressed against cold metal, standing on tiptoe on a box, straining chin on top. Would my past incubate? Would it return to disturb me? I have a large spoonful of cod liver oil every morning now, shuddering as it sluices down. I also have a memory of being given raw liver, but this may be elaboration or invention, a common failing for kids like me.

I invented my father once. There was a man who regularly used to watch as we played on the roundabout in the park at the back of the Plymouth home. I told everyone he was my dad. (I didn’t say he was Christopher’s; maybe my brother wasn’t there. My memories are sketchy and episodic, pixelated like worn VHS tape. No one to top them up.) The mystery man was watching over me, waiting, I told the other kids. He would be coming soon to take me away when he had found a place for us to stay. I didn’t understand when he didn’t come.

JULY 19, SATURDAY. It’s sweltering after two nights of thunderstorms, with temperatures hitting 32°C. There’s no more need to water, at least for now. I hit the plot in the late afternoon to check on progress. I have been sowing Mary’s ‘pumpkin plot’ with squash and courgette seed and I’m happy to see new plants popping through. I fork up a few potatoes, blushing Red Duke of York. As a child, I loved to dig the potatoes for weekend lunch, lifting them in the hour before eating. They were always King Edward’s, boiled with apple mint when new, diligently scraped and served with salty butter. We grew peas, runner beans, strawberries (Dudley’s favourite) but it was from potatoes I learned the joy of growing food for the table, taking as much as you need for the meal and no more.

JULY 20. Back on the first bus, early Sunday morning. The success of the squash seed has inspired me to weed the pit and move Mary’s bags of manure. It’s not yet 7am and I am smeared with insect repellent and horse shit that has liquified in the heat. It is steamy, mucky work as I stack the sacks. I hoe through the bed, move a stray calendula and sow courgette seed. I am prone to over-sow, almost as though my faith in things is thin and I still don’t quite believe in miracles. (I do. I think I almost am one.) I weed through Mary’s beetroot, beans and chard and cull the choking strawberry runners. The first beans are ready on the first wigwam: blue Blauhilde and Trail of Tears. I pick a handful to add to the potatoes. We will have them steamed and served with butter, just like Mum and Dad. My boots and trousers are smeared with manure. My shirt is soaked with sweat. My hair is sticking to my head. I am happy. A smart matron with two blazered schoolgirls pulls them closer to her as I pass. I am not dressed for Sunday society or even for the bus. Hampstead should have a tradesmen’s entrance.

JULY 22. Each garden in my life has its own identity, fulfils a different function, but the oldest and perhaps purest is the roof terrace at home. It was tiled with asbestos and packed with junk and dead bicycles when we moved in. I went a little mad at first, turning it into a country-cottage garden above an urban street. It was a riot of colour and contrast. The walls were trestled, none left bare. Roses rambled and added scent. Jasmine too. Early- and late-flowering clematis came next. We covered the floor in marble pebbles, brought in a weathered teak table and chairs. We eat dinner there on a summer evening, drink tea in our coats with the newspapers in winter. The roof terrace keeps me connected to the countryside. It’s an oasis of calm in Kentish Town. Pots are planted for colour, always brighter in summer.

Its identity has changed, matured with us. First to go were the trestles, the climbing plants and the once-white stones. Flowers became more individual, picked for personality, but there are always dahlias. Dudley thought them ‘common’ but I love them for their myriad shapes and strong colours as they ease the shift into autumn. There is a Magnolia stellata because its flowers signal early spring but mostly the roof terrace is a gateway to our piece of sky, a place to potter outside.

1959. We have our own bedroom, our own bed. But the truest sign of home is our dressing gowns. To be worn watching TV or after a Sunday-night bath, shiny for the new school week, downstairs for a goodnight peck, ours are brown wool, plain with a piped edge. My cord is blue and white, Chris’s is red and white like a barber’s pole, the colours of Manchester United, his favourite football team. Local Plymouth Argyll lose too often for his liking.

1960. Seven-year-old Christopher looks like Alfred E. Neuman from Mad magazine: gap-toothed, freckle-faced, wide cheeky grin. He is growing. The past is beginning to fade. He has slipped its grip. He is made for village life. It is more forgiving than Mum and Dad. He rediscovers his appetite. He comes in from outside (he is always outside) to wolf down fuel for the afternoon. Roaming like a puppy, seeing what he can find. He is what he says on the tin: an eager kid who deserves a break, who’ll adore you if you adore him. It almost works, in the heady days before Lilian and Dudley’s caustic disappointment becomes more marked. He is alert, senses it long before I do.

Christopher tells me stories at night as we lie excited in our matching beds with matching candlewick bedspreads. I am jealous of his teddy bear with its stitched black nose and articulated limbs. I have a stuffed white Scotty dog, its legs too stiff and short to hug. We wear matching Ladybird Cosijamas, fleeced inside, no strings or buttons, almost American. We can’t believe our luck sometimes, like we have landed on the moon. Safety like we had dreamed of, a family like we’d hoped. The storytelling lasts about a year, not every night but nearly as often as I ask. They are mostly adventure yarns: pirates. I am big on pirates. The river calls me from outside our window, occasional small boats elevated into three-masted ships, skull and crossbones flying, bearded ear-ringed men, heavily armed, sabres between their teeth. I am an impressionable child, overexcited in the summer light. Christopher is kind. We are close.

1961. Christopher is left-handed. Neither Dudley nor the school approves. Both try to train it out of him. It is suspect in some way, ‘other’, an unnatural, un-Christian thing. The teacher hits his left hand with a wooden pencil case. He walks up behind him. Sometimes nothing is said. It is as though left is a link to the wild, to be suppressed. With Dudley, it is just ‘different’. Fitting in is a thing with him, no standing out. We are learning to be invisible, at the expense of Chris’s hand. It doesn’t work, of course. Christopher is good at being hit.

1962. I like to scare myself as a child. There is a tree in the darkest part of the lane behind the house where I like to linger. It is tall, maybe malevolent, its branches and bark twisted like something from Tolkien. Christopher always hurries past (though he is braver than me with bullies). I stop and wait, savouring the moment of fear as scary branches wave in the wind. By about 10 or 11 years old, I have graduated to an abandoned badger sett I find on one of my long walks along the river. It is buried into the bank. I crawl deep inside, under the exposed roots, the heavy Devon clay. Burrow in as far as I can. I lie there daring the roof to fall, to bury me in red soil. The appeal is enhanced by the feeling I might never be found, the thought I can just disappear. After maybe half an hour of lying there I go home for lunch. By age 12, I get kicks from a piece of shaley cliff where the path had been eroded. I look down at the white water and rocks, and slide. You can’t walk it, do it carefully. The only route is surrender, to guide the drop to a piece of broken path with your feet. I love to let go, see if I can cross to the other side, stand where no one else would dare. I never do it with anyone else. Secrecy is the thing. I grow out of it when I become interested in girls.

1963. Lilian’s mother has come to live (or more accurately, die) with us. Christopher has to give up his bedroom and move back in with me. It’s not going well. He is not happy and when he is not happy we fight and I lose. At least he is outdoors all day, while I am obliged to stay in and read to her. She sends me to the village to buy her bottled stout. Mum and Dad are teetotal, the only booze the Christmas cherry liqueur and Harvey’s Bristol Cream on the sideboard for guests who never come.

Mum and Dad don’t read, except Dudley’s local Western Morning News. There is only a scant handful of ancient books in the house. The old grandma is a bit bad-tempered and I don’t like the smell of her or her beer, but I am fascinated by her age, her drab clothes, her thin, lined mouth and the thought that she is near to death. So we sit in the curtain-drawn gloom in the summer afternoon and I read her Heidi. She is 84, from deep in the nineteenth century, like my Victorian stamps and coins, too far away for a small boy to comprehend. She dies one night while we are asleep. We don’t get to see her or go to her funeral, though we are allowed to join the tea with Lilian’s good tableware. Christopher is soon moved back to his room.

1964. Mum cuts our hair with clippers: old school, hand action, blunt. She is always snagging our necks. She is worse at cutting a fringe. I think she is nervous. So are we. Christopher screams like he is being butchered. He checks for blood. He hates sitting still. I think we are all relieved when crew cuts come in and we can go to the barber in Kingsbridge. They let me take a sneak through Parade and pore over its pictures of topless girls. They also have Health and Efficiency – smaller, less sexy pages of naked ping pong in a naturist magazine. I leave feeling almost a teenager, splashed with spritz.

JULY 23. Of course I am now concerned about the baby squash and courgettes in the heatwave. The weather has been baking for days, so I am back on the first bus with today’s bleary-eyed postal workers. It’s bright, the start of a maybe 30-degree day, but there’s cool in the early-morning air, the first spectral tendril of autumn. The plot will need water and I can be back home before breakfast. Bill is there when I arrive, communing with his allotment, waiting for the day. We talk a little about the benefits of growing seed at home. It gives them a head start, he says. A heavy wave of sweet pea hits me as I pass the corner by the plot. A pigeon is feasting on the elder at the end of the plot, flapping its wings anxiously to maintain its greedy balance. The berries are turning now. Autumn won’t be long. Mary’s runner bean wigwam is flecked with flower and the bush beans are breaking through. I am more worried about the borders. Bindweed is creeping its way into the strawberry bed and the lovage is being tethered to the ground like Gulliver, sporting parasitic blooms. I grab a handful of beans. I have been bitten again and am starting to scratch. I soak the pumpkin bed, grinning at the new growth. Watering may be the best feeling in gardening. By 7am I am back on the bus, refreshed. I need breakfast and a bath.

SUMMER 1964. I have an appointment to be beaten. It is my choice. Dudley had been renting the field to the farmer for his cows to pasture but some escaped. It is our fault. Christopher and I have made a den in the hedge, a hideout for outlaw brothers after robbing a stagecoach or train. But the cows broke through and one became trapped in the river mud. I remember it lowing down the valley as the tractor tries to pull it out. It is freed eventually, it doesn’t drown, but the farmer’s nearly lost a beast and Dad is incandescent. He decides we can choose our punishment: to be caned or to miss TV for a week. No great loss, I think. We have BBC until 7pm, Dixon of Dock Green on Saturdays, maybe Doctor Who. The only person who can pick up ITV is the local coroner, who is given dispensation for a giant mast in the garden for his aerial, maybe because he spends his days with the dead.

Christopher goes for the TV option. I choose the beating. Just before bed I head downstairs in my dressing gown. I am scared but I want the anger over. Christopher waits, the thought of (another) beating unbearable. Mum and Dad are sitting in the living room by the anthracite fire. He has a garden cane beside him, a few cream crackers and cheese, a blue mug of Ovaltine. It is almost as though he is worried he will need a snack to replenish his strength. I am bent over his knee, my dressing gown has been removed. I think I am crying. I am hit once, maybe twice, but he doesn’t have the heart. After half an hour of Z-Cars, I return upstairs, triumphant but tear-stained. Christopher is angry I’ve almost escaped. I am furious the next day when his sentence is rescinded. There is no justice.

JULY 27. I had to leave the allotment yesterday; it was too hot to garden. I had contented myself with moving a few sunflowers and courgettes. I haven’t grown sunflowers for a while; the last were self-seeded. They grew like Jack and the Beanstalk, creating a shadowy canopy three metres tall. But I discovered seed in the bottom of my bag and I couldn’t control myself. I pick through radishes. They are big, round and red like kids’ lollipops but eat like crisp, mustardy apples. I cut lettuce for lunch and chard for weekday dinners, and gather a few multi-coloured handfuls of beans. It is too hot to work: days of mad dogs and Englishmen.

First thing Sunday morning, I am back. It’s cooler now so I lift the last of the calendula, tying a favoured yellow flower to the wigwam to save for seed. I weed through vegetable beds and train sweet peas. Mostly, though, this morning is about watering. I might not get back now for a couple of days so I soak everything in. The allotment site feels a bit abandoned. I miss seeing Mary.

1964. Being in the church choir is unavoidable for a village boy in Aveton Gifford. Only posh and ‘problem families’ are exempt. It is an infallible way to tell. Every week we pull cassock and surplice over our Sunday best and add our unbroken voices to the service. I faint once in the summer when the air is heavy, and come around to the sound of my feet drumming on the raised wooden floor. Wednesday evening is choir practice. There is sometimes a wedding on Saturday. Dudley never goes to church. Lilian goes twice a year: Easter and Mothering Sunday, when the church distributes the bunches of primroses we have gathered in the week. My favourite service is harvest festival. Hymns about ploughing fields, altar bread shaped like a sheath of corn, a table of fruit, vegetables, flowers and a few random tins of soup.

I don’t much like the vicar and he doesn’t like me. I don’t do sports, play cricket or football in the vicarage grounds like other boys, although Christopher excels at both. I prefer my own company, which the vicar doesn’t trust. One Wednesday evening, waiting for choir practice to start, I decide to stay outside in the sun. Christopher’s plan to blackmail me is undone a couple of days later by a knock on the door. The vicar and the village policeman (it seems bunking off village choir is close to a crime in the Sixties) stand there. Dad doesn’t invite them in. They think he should know, the vicar says. Perhaps bad blood will out. A priest and cop have come to our house. I have brought disgrace. I return to church and the choir, lesson learned. Back to singing solo, back to Advent weekend afternoons touring old people’s homes in brown-face and a beard and crown, a king in a Christmas carol. The vicar is probably right, I think. A rebellion has begun.

Muhammad Ali is our first hero, still called Cassius Clay when we listen to his fights on the radio (the wireless, as Dad always calls it). Christopher at first prefers Sonny Liston, impressed by his brutal efficiency. Dudley disapproves of them both but despises Clay’s cockiness. I love his swagger. Christopher and I don’t share other heroes, except Eusébio in the football World Cup in 1966. Christopher is for mop-top Paul and Ringo, I am for George and John. We don’t often like the same music or people but Ali is a unifying force. Christopher admires him for his boxing; I love him outside the ring.

1965. Dudley is prone to strange schemes and fancies. The Christmas trees, the poor chinchillas he keeps caged in a shed. The barn is converted for battery chickens, stacked high like Tesco. There are two sets of lights, one white, one red. The sight of blood from a crushed or cut bird sends the house into a frenzy but switching the light turns the red blood brown and the birds soon settle. I am never quite happy in the barn, picking eggs, spotting corpses. The mis-sexed young cockerels are the first to go. Don’t call so loud and proud, I want to warn when they show off their crow. My dad will hunt you down.

One day, two white goats appear. Dad’s been reading Farmers Weekly. We drive them miles to be mated, the first step to producing milk. I have never come across anything that stinks like a stud billy goat and wonder why Lilian and I are watching while they have sex. Must be a farmer thing, I think. I became fond, though, of the nannies in the field behind the house, fascinated as their bellies balloon. I think their babies will be like having lambs (Christopher is forever coming home with stories of rejected young sheep being kept in an Aga drawer). The big day comes. I rush home from school. There are no cute baby kids gambolling in the paddock or nuzzling their mother’s milk. I am confused. They were male so I clubbed them, Dudley tells me matter of fact. When I ask where their graves are, he points to the cesspit. I think I hate him a little that day.

The main trouble with the goats is no one likes their milk. We are having it in tea, on cereal, on our porridge. We are spared from drinking it straight. Dad is the first to switch. I am soon back to picking up his milk from the farm. We kids have to stick with goat for a while: it is good for growing boys, he’s read. But one day they have disappeared, as though they never happened. I wonder why we don’t get to say goodbye. I don’t go near goat’s cheese for 20 years.

There is a photograph of me in my final year of primary school. I am sitting up straight, blond hair neatly combed, looking into the camera, superior smile on my face. Pure Midwich Cuckoo, pure Peter Drabble. The rescue operation appears complete. Like our river cottage, I have been rebuilt into something smarter. Gone for now the questioning eyes, to be replaced with overweening confidence. I am head boy at my small Church of England school, garlanded in gushing valentines and the 11-plus. Grammar school is next. There is also, though, an uneasiness about my last year there. A girl from the estate is humiliated in class. She renders the summer sky yellow, the wheat field blue. I like the painting’s boldness, its originality, but the teacher humiliates her, toys with her like a cat showing kittens how to torture mice. We are being taught about more than English and maths. This is a lesson in class, about who her parents are.

Christopher is becoming crueller. The hunted grows to be the hunter; the abuser rather than the abused. It is simple, the psychology. The Drabbles have withdrawn their favour. His hurt has to be displaced. He turns to shooting random birds and rabbits; breaking wings, breaking legs. He sends in dogs. He turns on Mum and Dad, snarls his anger. He turns on me. I am blinded by other loyalties, too young and stupid to see. He grows to like a fight, my brother; is more of a force at school (I have sometimes cause to be grateful). Ironically, by the time he is a boxer in the army, Dudley brings him back into the family fold. It is my turn to be exiled.

Christopher is already at secondary school in Kingsbridge, the local market town, learning to curse, spray power words around like cunt and fuck and twat. He is a Jenkins, running with a tougher town crowd, I am a Drabble, still tied to my village primary. By the time I get to Kingsbridge, the grammar and secondary schools have merged, the new comprehensive classes streamed. I am in 1.1, year one, top tier, Christopher in 2.5. Our drift apart is official, as if we are not brothers any more. What we had is almost invisible.

It isn’t until secondary school that I realise how old my mum and dad are. It is a year of Bob Dylan, The Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Sandie Shaw. BBC newsreaders sport longer hair, longer collars, wider and brighter ties. Dad watches The Supremes on TV and says unfortunate things. Other kids have posters in their bedroom, their fathers will grow their hair. Lilian and Dudley are 20 to 30 years older than the parents of other kids in my class, their lives forever defined by the war. Even their names speak of another century.

Each year of the mid Sixties adds a half-decade to the differences between us. The questions they have raised me to ask become more difficult. What about apartheid and Vietnam, I demand, though their politics never waver. Clothing becomes an issue. We aren’t allowed jeans. I pine for a pair of Levi’s. I take a paper round and start buying records, though we only have a radio for Dudley’s classical concerts. The person I want to be is being redefined, away from Mum and Dad’s plan. I must be a source of worry to them.

From five to 13, I have loved my village life, our dog, our donkey, but now I long for a life less defined by who my mother and father are. Lilian despairs, the threats to ‘send us back’ increase, her love less unconditional by the day. Dudley becomes more angry while I become more defiant. Christopher sulks and stays away ever longer.

It isn’t yet hopeless. I am doing well at school, and Christopher is promoted a class each year: 2.5 became 3.4, 4.3: an A-level stream, but we don’t know our childhood is over, a chill teenage winter is coming. A care crisis plan is about to be put into action. We will never be the same. I have stupidly forgotten the lesson about always earning conditional love.