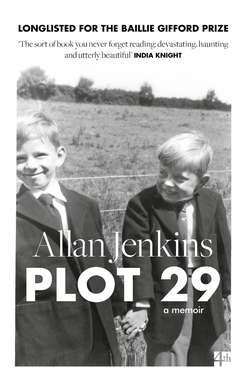

Читать книгу Plot 29: A Memoir: LONGLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD AND WELLCOME BOOK PRIZE - Allan Jenkins, Allan Jenkins - Страница 13

August

ОглавлениеAUGUST 3. Plot 29. Two days of hoeing, digging, raking – clearing weeds from Mary’s beds. Her broad beans have gone over, pods fat and ripe, hanging heavy, waiting for her. The onion bed is also overgrown. Greedy calendula has taken over, with sycamore seedlings in support. Bindweed by the wheelbarrow-load has been creeping in, smothering other plants. Mary’s cold frame is nurturing weed. Attack is the best defence.

Bindweed to the waste bin, calendula to the compost, seedy perpetual spinach too. I clear the frame and lay out a sack for onions and shallots. It is sweaty work in sultry weather but we need clean beds to sow. September is only four weeks away, the sun is starting to dip, sap is beginning to slow.

By teatime Sunday, I am sitting, hands a bit torn, shirt a bit sticky, when I hear my name behind me. Mary’s standing there, a little tired. I show off the beds like a proud schoolboy handing in his homework. She smiles. We talk about her crop rotation. She has a plan at home she says she will send me. We admire the runner beans and the sweet peas I have just finished tying (the sweetest-smelling job). The pumpkin bed is thriving. Her courgettes are flowering and the rest not far behind. She gathers herbs and rocket and beans. I press her to take some of our chard and red-hearted lettuce. Howard and his family are on holiday and I am daunted by how lush everything is. Mary hands me seed to sow. I’ll be back in a couple of days.

1968. It is decided I should go to boarding school. Plymouth children’s department will pay and there will be a scholarship. I am mostly messing about at Kingsbridge but coming top or near it in exams. My French master hates me for it. My writing is sloppy, a source of shame to Dad, whose copperplate is immaculate. The teacher makes me rewrite my French exercise book overnight. It starts neatly until I see it is too slow. He slippers me the next day. Punishment is measured in strikes of three or six, with the teacher’s choice of weapon (he favours a gym shoe) on your non-writing hand. The notebook is worth six, the small man almost jumping as he hits. After he’s finished, I smirk my contempt. He has me hold out my right hand for another six. I walk back to my seat in angry tears, girls are looking up at me, sad.

It isn’t just schooling. Mum and Dad are worried about sex, about me spending time with girls in their bedrooms listening to Jimi Hendrix. Dad loathes Hendrix, his black sexuality. The girls’ allure is almost as much in the soft colours and fabrics of their pop-postered rooms (mine is austere, almost military) as the thought I can slip a hand in underwear. Mum particularly seems obsessed by the idea of sex. Maybe it is the fear of my feral other mother. Christopher, meanwhile, contents himself with football and fighting, hanging out at the village pub.

Changes are coming, decisions have been made. The threats to send us back to Plymouth are more relentless. It is over. We are out. Boarding school and the army are presented as Mum and Dad’s only options for our future. I like the idea at first. It sounds like an adventure. I am good at new people and places. I have practice.

Christopher pleads to stay on at school for agricultural college, his grades have improved every year. He loves our neighbour’s farm and farming, is dug in deep in the village. He belongs here like no one else. I am too smart-mouthed, too strange, Lilian and Dudley too stand-offish. But Dad is insistent. Christopher is packed off early to the army. He will never forget or forgive them and I am not sure I do. In the summer of ’68, as the rest of the world seems set to change, our family fractures. It is sudden, savage, the shift.

AUGUST 5, 7.30AM. An early weekday visit to the allotment. I keep a shirt in the shed for watering or weeding, in case I have a meeting first thing and don’t want to be wearing mud. I am here to sow, easier in the morning air. I cut sticks and string, give the bed another hoe. There will be short rows, some with Mary’s seed and a couple of cavolo nero, lettuce, red mustard and rocket. A blackbird lays the soundtrack and a robin keeps me company. A few feet away, pigeons hang in the skeleton tree like vultures waiting for something to die. Within an hour or so the sowing is done. I water it in. The forecast is for rain but I can’t resist soaking the rest of the plot. The beans and squash are greedy and it relaxes me before the bus to work (no time to walk now). Mary will have her autumn leaves. I wander around, reluctant to leave. The corn looks as if it is ready to eat, the cobs are fat, but they will have to wait till Howard is back. A young black cat, no collar, passes by nervously.

1968. Battisborough House is set back from a cliff not far from Plymouth. It is a Kurt Hahn school, the Outward Bound man, whose most famous school is Gordonstoun, where Prince Charles has just been head boy. Its reputation is based on character-building. No one goes to Battisborough for its academic excellence, though it is there in its small class size and dedicated teachers. It is founded on a Germanic ideal crossed with an English public-school ethos. There is emphasis on activities. We wear two uniforms: navy blue for the morning and grey for after tea. No ties or blazers but open-neck shirts and sweaters and corduroy shorts (tough if, like me, you think shorts are for summer or primary school), long flannels for church. There are no girls, except a couple of teachers’ daughters who live on the grounds. I wonder if they are ever as longed for again. I date one, the same age as me. We kiss. I rub her skirt and shirt. There is to be no beating, an ethos from the headmaster, David Byatt, who leads by example. I am to test this resolve. The boys who are good at boarding school are the ones unbroken by starting there aged seven (there are, of course, casualties), followed by the boys who start at 11. The odds are against boys who arrive aged 14 because they cannot live at home and still call themselves part of a family.

I love my first year here, though it is at Battisborough I discover my Devon accent, a shock when the Sony machine replays my village burr, less of a shock when other boys mimic it. There is a maximum intake of 60 pupils, though it is down to 36, little more than a class at Kingsbridge. I absorb it all like tissue, the English classes of maybe eight, with a teacher who is interested. ‘You like Herman Hesse, try Günter Grass.’ Wives also teach. I am impressionable, eager, almost desperate to learn. It looks as if it will work. I jump a year in English, Maths and French (no psychopathic slippering here, a less messy exercise book). Every afternoon there are sports, though I am less keen on this. I hate rugby in winter. There are other activities – tennis at the courts of the local landowner’s house or gardening. I tend plants and trees and hide behind rhododendrons to smoke Player’s No 6, the schoolkids’ cigarette of choice. But the afternoons I like best involve cross-country running, unleashed like a lurcher over cliffs, across beaches and along my beloved south Devon estuaries, very nearly free. Battisborough is also where I learn more subtle social lessons, that class and cars matter. Frugality can be suspect. At the end of term a procession of vehicles comes to pick us up – wide Mercedes, fat American convertibles, and the air-cooled splutter of Dudley’s little Fiat 500, not yet the cult car it will become. But I am happy, I know I can adapt. I have done it before.

AUGUST 8. Glorious. Crimson sky. Every day, autumn tightens its grip. Timing is important, crops for winter have to be established before the light and warmth fade too far and energy retreats. Autumn and winter salad mixes must go in, late radishes and hardy herbs. Plans, such as they are, start to be formulated in my head. There is a thought of green manure this year: clover, physalis, vetch. The question is how much of the plot should be covered and what Mary wants. There will be digging to do, a war on weed.

1968. Dad isn’t one for swearing, an occasional bloody if Mum isn’t around. So when Christopher tells me what bugger and prat mean it sounds implausible. The only time with Dad is once in the car when he crashes the gears. We’re alone. I am 14. Old enough to hear him say fuck.

All change. We cannot find your mother but we have found your sister Lesley and your father, the care worker tells me (this use of ‘care’ in ‘children in care’ a Goebbels-like lie). Things are drifting dangerously at home, Christopher is unhappy in the army. I am away at boarding school. Dad has sold Herons Reach to Lilian’s nephew, who wants a bolt hole from Kuwait. Gone the river, gone the field, broken the sense of security. Dudley is clearing the decks.

I am wanting to know more about Alan Jenkins. Mum and Dad are probably resentful, though they have never said so. It is as though it is a matter of poor manners and ingratitude, not identity. Asking is discouraged throughout the system. It is wrong, the ‘right to know’. I am searching for an escape plan. If one door closes, can another open? But if Lilian and Dudley don’t want us, why would anyone?

A photo strip arrives at school of a skinhead girl grinning into the camera. I pore over it. Can I see a likeness? It will be a first for me (Christopher and I are never alike in looks or temperament, though tightly bound together like corn). Most families share the same eyes, smile, same mouth. They swim in a sea of recognition, reassured of where they belong. I think I have always been longing for a face that could be connected to me.

My sister and I exchange excited messages. Lesley writes of her life in Basildon, a new town in Essex, with her – ‘our’ – dad. I show off from my posh Devon school.

I cannot discuss it at home, the wheels are coming off. But I pine for Lesley’s letters, like adolescent love.

I have long wanted a sister, someone soft. Perhaps finding a dad is less important because Dudley has filled that space. A mum, though, is different, a primeval pull. It isn’t anyone’s fault, just how it is. Maybe, as we get older and more male, Lilian still mourns the baby girl she never had.

I worry why she isn’t more affectionate. Kisses, quick cuddles are for when I am sick. I had divined early on that it was because she was too thin, her breasts couldn’t carry enough chemicals for love. Other boys’ mums are more curved, more tactile, invite you in, feed you, sit on the same sofa as their sons. I am envious of friends who are held. It has been a long time. I am in need of mothering.

There isn’t, though, a mother to be found, the care worker says. For now, a sister and a father will do. Letters are exchanged from our twin alien worlds. Lesley’s handwriting is neat and loopy, sometimes comes in green ink.

For the first time, the end of the summer term means a train on my own to London and not a short Devon drive. I am at Paddington Station and my name is called over the Tannoy. Will I come to the station manager’s office. I am sick, a little scared. We would have had counselling for it now, this seismic shift in who we are. The tidal pull of blood and belonging.

Suddenly we are in the same room, family parted 10 years before. Lesley with her Prince of Wales pattern skirt and long, green nails, her Essex accent and smile. With my dad, Ray, it is different, something is wrong, though not from his side. He isn’t the man I expected to see, the one I’ve been waiting for. I rationalise it later: how could anyone live up to the hope, the longing I have buried? I had Hollywooded the moment: the glamorous sailor back from the sea, the white fence with Mum and me waiting. Ray is taking me home, what more could I want?

Basildon is impossible. A New Town, an east London overspill, surrounded by a ring of factories: Ford, Ski yoghurt, Carreras cigarettes. Lesley, my sister, is called after Dad, Leslie Ray. I am a village kid from Devon, who has nearly been to London once on a long day trip to Heathrow Airport with Sunday school (people used to do that, a glimpse of the future and the rest of the planet through pilots and ‘aeroplanes’). Otherwise my world is limited to a twice-yearly trip to Plymouth, once in summer to buy shoes and again before Christmas to buy the Norwegian sweater (mine in blue, Christopher’s in red) that is always our present. We have lunch in the department-store restaurant, maybe a film if there is something suitable.

Basildon is bewildering. Identical estates laid on an identical grid, but I stay for the summer holidays, hanging around the record store to listen to music in booths or at the swimming pool by Ray and Lesley’s flat, if I don’t get lost (I am always lost). I am fascinated by Lesley, the way she speaks, the way she’s dressed, her taste in skinhead music, her feather-cut friends, the soap operas she watches. My relationship with Ray is more complicated. He won’t talk about my mother, show me photos, even tell me her name. He refuses to speak about his life with her or his wedding. ‘You must never ask me, it is better you never know!’ It feels odd to hit a wall so soon.

Ray is a cook but also a Pentecostal evangelist to be seen proclaiming the name of the Lord in Basildon town centre every Saturday. It is like living in a soap series I have never watched but Lesley does, Crossroads or Coronation Street. The connection to the past I have pined for still feels far away. I finally have sex, though, with a girl from the swimming pool on a piece of waste ground outside town. She is older, has more body hair, but it is a bit boring. Another disappointment, another longing unresolved.

1987. I am in need of a birth certificate for a new passport but it seems I don’t exist. Alan Jenkins born on my birthday isn’t to be found. I am confused, so ask at the enquiries desk. Search the adoption register, the man says, if you are not there, your birthdate is wrong. Most of my life I have carried the understanding of caste, that although they had changed my name, had played our parents, the Drabbles didn’t adopt us. I was never sure why we hadn’t made the grade. I was proud to bear the mark of foster child but adoption is another level of belonging, gossamer close to never having to worry about being sent back, no longer on sufferance. A family of your own. A place to stay.

I search the adoption register. And immediately there it is in black and white. All this time, my history mouldering, smouldering, in this London room. Alan Jenkins’s certificate. Adopted by Leslie Ray Jenkins, it says, at 12 months old. I am lost. I had wanted a passport, a long-haul holiday, not the fabric of who I am to lie threadbare in my lunch break.