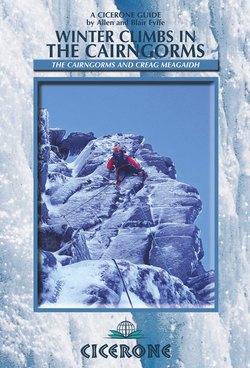

Читать книгу Winter Climbs in the Cairngorms - Allen Fyffe - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The major climbing venues of the Cairngorms provide some of the finest winter routes in Britain. From the remote corries of Braeriach and Beinn a’Bhuird to the magnificent cliffs of Lochnagar and Creag an Dubh Loch and the readily accessible Northern Corries of Cairn Gorm, every aspect of winter climbing is to be found here. There are long, varied routes and short technical test-pieces; there are pure ice climbs as well as mixed routes to rival any in the country. Building on previous editions, this guide offers a selection of the best routes in each area – and, where possible, routes of all grades are given. Where there is a variety of routes, a number of climbs at a similar standard are detailed to allow for some choice should conditions or availability dictate a change in plan. Many of the routes follow fairly natural lines which, once embarked upon, should be relatively easy to follow, the exception being some of the more recent hard mixed routes which require a more detailed description.

Scottish winter climbing can be a hazardous pastime. The weather is often unfavourable and can change with startling suddenness, transforming a pleasant excursion into a battle for survival. Too many people have underestimated these mountains and paid the ultimate price. It is essential to be well equipped – both physically and mentally – before setting off on a winter route. Having the correct equipment must be accompanied by the ability to use it properly. When the weather, the conditions and the climb are right, then winter climbing in the Cairngorms can offer an unforgettable experience.

Conditions

Good climbing conditions can occur in this area at any time between November and April, although February and March tend to be the most reliable months. In some years winter climbs can be in condition as early as October and as late as May. Winter ascents have even been made in June!

Part of the challenge of winter climbing is correctly predicting climbing conditions and choosing suitable objectives accordingly. Knowing when, for example, it is better to go for a buttress route rather than a gully, or whether to push your grade or try something well within your capabilities, can make the difference between a great day’s climbing and an unpleasant and potentially dangerous expedition. However, predicting conditions can be tricky, especially for those based far from the mountains. Observing and learning how the weather affects the climbs is the first stage – how much thaw and refreeze is required to produce good ice, how long it takes for the turf to freeze and for the rocks to rime up, whether the ice will be hard and brittle or soft and plastic. In the past this knowledge was often hard-won, with many climbing trips ending in disappointment due to poor conditions in the chosen venue. These days, however, with a plethora of up-to-date conditions blogs, web cams and winter-climbing forums, it is easier to stay well informed on current conditions, especially for popular areas.

A pair of ptarmigan in winter plumage

The Cairngorms are further from the sea than other Scottish winter-climbing areas, and many of the cliffs are very high. This has advantages and disadvantages. Early in the season the Northern Corries of Cairn Gorm, and the other higher crags, are among the first in the country to come into condition. Freezing temperatures and a northerly wind blowing cloud and snow showers onto the crags can rapidly build rime, bringing snowed-up rock climbs into condition very quickly. However, for mixed routes that rely on vegetation it is very important to wait for the turf to be properly frozen before they are climbed to minimise damage to the ground. Some routes in the Northern Corries, such as Invernookie, are getting progressively harder as the turf disappears because they are being climbed in unfrozen conditions. It can be a frustratingly long wait for the ground to freeze properly in the autumn, especially if snow falls and insulates unfrozen turf. Once frozen, however, the turf takes a long time to thaw out again.

Conditions generally do not fluctuate as rapidly in the Cairngorms as elsewhere, and this means that the build-up of good snow-ice can take longer than on other cliffs. It also means that deep soft snow can remain unconsolidated for long periods, making the approaches to the crags arduous, and then requiring a lot of clearing once on the route. In these conditions the buttresses often give better and safer climbing than the gullies. On the other hand the more consistent temperatures mean that climbing is often possible here after a large thaw has stripped the crags bare in other areas.

Routes which rely on seeps and springs for their ice tend to require a period of very cold weather to come into condition. These routes, along with the steepest of the buttress climbs which hold little snow at the best of times, may strip bare after only a short period of thaw or bright sunshine, especially those that are south facing and later in the season. Some routes require a number of melt–freeze cycles to bring them into good condition. These are often in their best condition in the middle to late in the season after a number of these cycles has built up the ice.

Winter climbing ethics are strongly held in Scotland, especially when it comes to mixed climbs on buttresses and ridges. To be in acceptable winter condition, buttresses should be generally white, there should be snow on the rocks, and turf should be well frozen. Snow on the ledges and dry rocks is generally not held to be sufficient, neither is a coating of hoar frost.

Early morning light on the approach to Creag Meagaidh (photo: Steve Fortune)

The size and scale of the crags and the approaches make the ability to navigate essential even for a visit to the closest of the cliffs. Bad weather can occur at any time, with winds of over 100mph being common, and gusts well in excess of that speed often being encountered. Gale-force winds may blow continually for days or even weeks at a time. Much of the high plateau is featureless, and in a white-out accurate navigation is sometimes needed to find the cliff – and more is often required to find the way back after the climb. To climb safely in this area requires sound winter-mountaineering skills.

Checking the weather forecast before setting off is an essential precaution. It can be obtained from most daily papers, the radio or television. However, the best source of mountain weather information is probably the internet. The Mountain Weather Information Service (www.mwis.org.uk) and the Met Office (www.metoffice.gov.uk) both provide free mountain weather forecasts, which can be accessed online and on some mobile phones.

Many climbers and instructors have a blog or conditions page. These tend to be regularly updated and can be a great source of information on climbing conditions. Less specific to climbing, but useful for an overall picture of weather and snow conditions, are the web pages of the ski areas. Cairn Gorm, The Lecht and Glen Shee ski areas all have webcam images and snow and weather reports on their pages. There is a weather station on the summit of Cairn Gorm, which can be a very useful source of real-time weather information. The SAIS avalanche reports and blogs (www.sais.gov.uk) are another useful source.

Routes and Grades

The usual winter-climbing two-tier grading system has been used in this guide. The first grade, a Roman numeral, indicates the overall difficulty of the route. This gives some indication of seriousness. The second, an Arabic number, indicates the technical difficulty of the climbing.

Grade I

Uncomplicated snow climbs that have no pitches under average conditions. However, cornice difficulties may be encountered, there can be dangerous run-outs, and the avalanche hazard is often high in the snowy confines of a Grade I gully.

Grade II

Gullies that have individual or minor pitches or high angled snow. Cornices can be difficult. Also the easiest buttresses under winter conditions.

Grade III

Gullies that contain ice in quantity. There is normally one big pitch and often several smaller ones. The buttresses are fairly sustained.

Grade IV

Routes of sustained technical difficulty. Short vertical steps or longer sections of 60–70° ice expected in gullies. Buttresses require a good range of climbing techniques or are long and sustained.

Grade V

Climbs that are difficult, sustained and generally serious. On ice climbs long, steep and sustained pitches are to be expected. Buttresses require winter techniques such as axe hooking and torquing, combined with competent rock-climbing ability.

Grade VI

Ice climbs have long vertical sections or are thin and tenuous. Buttress climbs include everything in Grade V, but there is more of it.

Grade VII

Usually buttress or face routes that are very sustained or technically extreme. If ice is involved, it is extremely steep and/or thin.

Grade VIII and above

Very hard and sustained mixed routes. By the time you are considering this sort of grade, you should have a fair idea what is involved.

The technical grades, which are given by the Arabic number, are based on the technical difficulty found on ice routes of Grades III, IV and V. The Roman number indicates the overall difficulty of leading the route, taking into account the seriousness, technical problems, protection, route finding, sustained nature, etc. The system is similar to the way adjectival and technical grades are used to grade rock climbs. In this way a V,4 would be a technically easy but serious Grade V route, probably on ice; V,5 would be a classic ice route with adequate protection; V,6 likely to be a classic buttress route – harder but better protected than a V ice route: V,7 would be a technically very difficult climb but with a short crux and good protection. It is unlikely that the technical grade will vary by more than two from the overall grade.

Grades are given for average conditions, which may or may not exist. A big build-up of snow may make gully climbs easier but buttresses harder, as more clearing is required to find holds and protection. The grades of some routes can vary dramatically, and on some of the harder climbs occasionally conditions are such that even classic routes may be one or even two grades easier than that given. The absence or presence of even one good placement can make a big difference to the difficulty of some climbs. Occasionally a split grade is used in the lower grades to indicate a climb whose difficulty varies according to the build-up – such as when pitches disappear to give easier climbing, often later in the season.

Brian Duthie pulling some steep moves on the first pitch of Fall-out Corner (Number 4 Buttress, Coire an Lochain) (photo: Henning Wackerage)

A combination of short daylight hours and poor weather gives Scottish winter climbing an Alpine-like urgency. Because of the need for speed and the variability of conditions, the use of aid tends to be less rigid than in summer. However, these two requirements, speed and aid, are not always compatible. The more aid used, the longer it takes and the risk from approaching darkness increases.

Although pegs are still required in some situations, climbers should attempt to apply modern rock-climbing ethics as far as possible to winter climbs. Fortunately, it is often the gullies with their poorer rock that require pegs, while many of the more open buttress routes on better granite can be adequately protected with nuts and so on. Attempts should be made to limit the use of pegs on all climbs, especially those that are also popular summer climbs.

It is worth selecting a climb with conditions in mind for both safety and enjoyment. Climbing behind other parties on ice routes usually brings with it the danger of dislodged ice, and this is best avoided if at all possible. In thawing conditions there can be a very real danger from ice and rock fall, particularly in some of the easier gullies, where the rock may be of dubious quality and can be loosened by freeze–thaw action during the winter. Hooking and torquing of axes behind blocks can leaver them off, especially if the ground is not well frozen. There have been serious accidents resulting from both rock and ice fall.

Route Lengths

Route lengths are the combination of pitch lengths. For some routes, especially easier gullies, this value is approximate, as there is often not a clearly defined boundary between the approach slopes and the start of the route. Ropes of 50m are sufficient for the majority of routes, although 60m ropes will sometimes be quite handy, especially when trying to run it out to the plateau. Pitch lengths are given on some routes to help with route finding. On many easier routes where it is possible to belay in numerous places, pitch lengths are often not given or required.

Recommended Routes

As this is a selective guide some routes have been excluded, and all the climbs that have been included are worthwhile and have some positive features. However, a star system has been used to indicate quality. This has been done by considering all the features which make up a climb – length, line, escapability, how sustained it is, and the quality of the climbing. Since winter is such a variable environment, climbing routes in poor conditions may not warrant their stars. The stars are pointers – something to argue about – and, above all, subjective!

Aladdin’s Seat in Coire an t-Sneachda, with John Lyall standing on top (photo: John Lyall collection)

Diagrams and route numbers

In the guide all the main crags are illustrated by topo diagrams, although all routes may not be shown. For those crags without diagrams, the text should be sufficient to locate and follow the routes. Most crags have the routes described from left to right, but in a few cases, such as Hell’s Lum, where the normal approach to the crag is from the right, the routes are described from right to left. In such cases this is clearly indicated. All directions refer to a climber facing the cliff unless otherwise stated, such as for descents. Not all routes are shown (numbered) on the diagrams in order to avoid overcrowding. A broken line on a diagram indicates that a section of the climb is hidden. The numbered routes offer good reference points for adjacent non-numbered climbs. Indexes of routes are given at the end of the guide.

Maps

The climbing areas described in this guide are covered by a range of maps in the Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 Landranger series. The Lochnagar/Creag an Dubh Loch area is covered by Sheet 44, entitled Ballater & Glen Clova; the Cairn Gorm area is covered by Sheet 36, Grantown & Aviemore. Part of the area is also on Sheet 43, Braemar & Blair Atholl.

The OS Explorer maps at 1:25,000 scale also cover the area. Use Sheet 403, Cairn Gorm & Aviemore, for the Central and Northern Cairngorms; Sheet 404, Braemar, Tomintoul, Glen Avon, for Beinn a Bhuird; and Sheet 388, Lochnagar, Glen Muick & Glen Clova, for Lochnagar, Creag an Dubh Loch and Glen Clova.

Creag Meagaidh is covered by Landranger Sheet 34, Fort Augustus; Sheet 42, Glen Garry & Loch Rannoch; and Explorer Sheet 401, Loch Laggan & Creag Meagaidh. Harvey Maps produce the 1:25,000 Superwalker series maps. Three of these – The Cairngorms, Ben Avon and Lochnagar – cover most of the crags in this guidebook. Harvey also produce a series of 1:40,000 Mountain Maps, of which The Cairngorms and Lochnagar sheet covers most of the area.

The ability to use a map and compass correctly is essential for all winter mountaineers and climbers.

GPS systems can provide a useful back-up to more traditional map and compass skills, and it is recommended that they are used in this way, rather than as the sole navigational aid. Walking on the bearing obtained from a traditional compass will nearly always be steadier than following that from its satellite-driven GPS cousin. The location of the foot of some routes is given by a bearing from a prominent feature for some crags to aid their location in poor visibility.

Access rights

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 established statutory rights of responsible access to land and inland water for outdoor recreation and crossing land. These are known as Scottish access rights. The Scottish Outdoor Access Code (available from www.snh.gov.uk) gives detailed guidance on the responsibilities of those exercising access rights and of those managing land and water. The Act sets out where and when access rights apply, and how land should be managed with regard to access. The Code defines how access rights should be exercised.

Loch Avon, Carn Etchachan and the Shelter Stone Crag

The three principles for responsible access apply to both the public and land managers.

Respect the interests of other people – be considerate, respect privacy and livelihoods and the needs of those enjoying the outdoors.

Care for the environment – look after the places you visit and enjoy, and care for wildlife and historic sites.

Take responsibility for your own actions – the outdoors cannot be made risk-free for people exercising access rights; land managers should act with care for people’s safety.

Equipment

Ice axe and crampons are essential for any winter outing, whether walking or climbing. For climbing it is assumed that two tools are used, with either curved or inclined picks. Climbing with leashless tools is becoming more popular at all grades – however, they lend themselves particularly to the higher grades. Unless you are very confident with these tools, lanyards connecting them to your harness are recommended.

Crampons should have front points and be adjusted accurately to fit the boots. They should be securely attached to the boots by either straps or a clip-on arrangement. The boots themselves should be rigid, with a good sole for step-kicking, and be able to take crampons. Ill-fitting crampons can be a positive danger in winter.

For any winter climbing a helmet should be considered mandatory. There is always the risk of being hit by falling ice, even from the most skilled and considerate leader. Besides, a helmet provides good insulation from the cold!

A normal rack of gear covering a reasonable range of crack sizes is usually sufficient. Camming devices can still work well on granite in winter if the interior of the cracks are ice-free, but should always be treated more carefully than in summer. A few pegs may be necessary on some routes, but the majority of climbs, especially on buttresses, can be done safely without them. Ice screws are obviously needed on ice routes. One or two drive-in/screw-out pegs such as warthogs, or bulldog-style ice hooks, are quite versatile and can be invaluable when hammered into frozen turf if nothing else is available. Try to match the gear to the climb and avoid being burdened by unnecessary weight.

A complete water- and windproof shell outer layer is necessary, as is spare clothing and food. A synthetic belay jacket that can be pulled on over a waterproof shell is also useful in a team. As the name suggests this can be worn by the belayer, who seconds the pitch wearing it and then passes it over to his/her partner before starting to lead the next pitch. Also essential is a head-torch and adequate battery power. A bivvy bag of some type is a worthwhile addition. Extra gloves are extremely useful, especially in damper conditions, when having dry and, hence, warm hands for at least part of the day is something to be savoured. Several extra pairs may be worthwhile in certain conditions. Even the best climbers will not be able to complete their route if they do not learn what to wear, and how to wear it, in order to keep warm and comfortable.

Mobile phones

Coverage is mostly good, but users should be aware of the limitations of mobile phones, especially if tucked away inside any of the corries or deeper glens. When using a mobile phone to raise the alarm, dial 999 or the local police station and ask for Mountain Rescue, give your number to the police and remain switched on until the rescue team arrives or you are given the all clear to switch off. Remember that your phone will make 999 calls on any available network, so it is worth trying even if your phone shows no coverage on your network, and whether or not there is credit on your account. Texting is often a useful of way of preserving battery life.

Avalanches

Avalanches occur in the Cairngorms and on Creag Meagaidh every year, often with tragic results. Anyone intending to climb or walk in the Scottish mountains in winter is strongly advised to acquaint themselves with a basic understanding of avalanches. As well as various courses and lectures which are available during the winter months, there exist some excellent books on the subject, with A Chance in a Million by Barton and Wright being the classic text on avalanches in Scotland. The ability to judge the likelihood and consequences of an avalanche, and to know what to do in the event of an avalanche incident, could save lives.

Snow and avalanche

A basic knowledge of how and why avalanches occur is a prerequisite for learning how to avoid them. Storm cycles and changing weather conditions tend to build up a highly layered mountain snowpack. Avalanches usually occur when the bonds between adjacent layers, or that between the snowpack and the ground, fails. Changes that occur over time both within and between these layers can increase or decrease snow stability, depending on the circumstances.

Different types of avalanches exist and are generally classified according to their physical characteristics. An avalanche can release from a single point or a whole area (loose or slab); it may be the whole snow cover or only part of it that slides (full or partial depth); and it can be channelled or not (confined or unconfined). It may also be airborne or flow along the ground.

A full-depth avalanche on The Great Slab, Coire an Lochain

Avalanches are initiated because of either changing internal factors, such as bonds between layers being weakened by rising temperatures, or external factors, such as snowfall or a person walking or skiing on the slope. The details of the release process are complex and poorly understood. However, some basic principles are well known. Avalanches can release on slopes between about 20° and 60°, although slopes between 30° and 45° are the most likely to release, with about 38° being the optimum angle for slab avalanches. Above about 60° snow tends to slide off in small sluffs rather than building up to reach dangerous quantities. The greatest danger usually exists during and for approximately 24 hours after a period of heavy snowfall. This danger period is longer in cold temperatures, when the snow consolidates more slowly. Thaws, especially if accompanied by rain, produce a wet-snow hazard, as well as the danger of collapsing cornices. Even in the absence of snowfall or thaw, a significant avalanche hazard may be created by the wind redepositing the snowpack.

Avalanche types

There are various types of avalanche, and these tend to occur under different conditions and present different degrees of hazard.

Powder or loose snow avalanches typically occur during, or right after, a snowfall. Usually the failure begins at a point and spreads out down the slope in an inverted V shape. They are generally small in size, but in the confines of a gully they can be unpleasant and are sometimes large enough to knock a climber off.

A slab avalanche

Sgor an Lochain Uiane and An Garbh Choire from Ben Macdui (Cairntoul/Braeriach Amphitheatre)

A slab avalanche, on the other hand, occurs when a cohesive slab of snow slides on a weak layer. They are the most common, least predictable and, therefore, the most dangerous type of avalanche. This type of snow, called windslab, is formed when wind-transported, and therefore damaged, snow crystals accumulate in sheltered areas such as lee slopes. Windslab consistency can vary from soft to hard, depending mainly on the speed of the wind that transported the snow. Hard slab, in particular, is very deceptive, as it can be firm enough to walk on without sinking in and so feel safe to the unwary. However, it does tend to have a dull, chalky appearance and may squeak or creak when walked on or probed with an axe. Although most common on lee slopes, particularly below cornices, it can build up in unexpected places, even on windward slopes.

Wet-snow avalanches usually occur during a thaw, when the snow or its top layers become saturated. The extra weight and lubrication of this water can weaken the bonds between different snow layers, or between snow and the ground, and may cause a large area to slide. Although easier to predict, this type of avalanche can be particularly descructive due to the high density of wet snow. Wet-snow avalanches can harden rapidly on settling, and so it can be extremely difficult to escape from them unless this is done immediately.

Avalanche avoidance

Before starting out

Avalanche awareness should start long before the mountains are reached. Monitoring the weather in the days prior to a climbing trip is a basic precaution, with heavy snowfall accompanied by wind being the main danger sign. Long periods of cold temperatures tend to make any danger last longer, while a freezing level that rises and falls rapidly usually quickly consolidates the snow pack. Be aware of the recent and forecast wind direction, as the greatest danger is likely to be on lee slopes, the place where windslab accumulates. Consult the snow and avalanche forecast, and consider possible alternatives should conditions turn out to be worse than expected. Seek expert local advice – avalanches tend to have local characteristics. Have the appropriate equipment and know how to use it.

In the mountains

Ongoing observations on the hill should be used to confirm, and refine or adjust, your initial hazard evaluation. Avalanches occurring or signs of recent activity are the most significant indicators of an avalanche danger and should not be ignored. On the approach observe the nature of the snow on the ground and in the air. The behaviour of snow underfoot can be very informative. Cracking and breaking away of snow blocks from beneath your feet is an indication of slab and instability. Look for signs of recent windslab deposition. Spindrift is usually a danger sign, as even fairly light winds can redistribute huge amounts of snow, packing it in as windslab on lee slopes and in other sheltered locations. Even a light surface drift can produce localised danger, especially in the tops of gullies.

Signs of a rise in temperature – such as rain, wet snow, sun balls rolling down the slope, strong sunlight, and melting snow and ice – can all be danger signs, especially if large cornices exist. If the thaw is due to strong sunshine, then different slope aspects may make a large difference, with perhaps danger on south faces but safer northerly aspects. In these circumstances, slopes of a similar aspect and altitude should be considered extremely suspect.

Although general observation is important, a simple snow pit can give further information about the snowpack and its stability. A snow pit dug in a safe but relevant position for the suspect slope is useful. It is dug down to ground level or, more usually, to the level of a stable consolidated layer. The back or sidewall of the pit is inspected for snow layers of differing hardness. Significant differences in hardness between adjacent snow layers can be a warning sign. A pit can be dug quickly with an axe and need not be elaborate to give relevant information. Even the resistance felt when pushing the axe into the snow may reveal much about the layers. However, due to local variations in the properties of snow, any snow pit or test will only give information about one point, and must be considered as part of the overall picture.

Route choice and safety precautions

A number of factors influence route choice in avalanche terrain (here route choice is not limited to a climb, but includes all movement in the mountains). Ridges, buttresses and flat ground are safer than open slopes. Windward slopes are generally safer than lee slopes, but even here local variations in topography can create a localised avalanche hazard. Convex slopes are more likely to slide than concave ones, and gullies or depressions tend to concentrate avalanche depth and power. Even a very small area of windslab can represent a hazard if the run-out is into rocks, over a drop, or into a terrain trap such as a stream-bed or similar hollow where the debris can be funnelled and build up to considerable depths. Some very serious accidents have occurred where the slab that released was only about the size of a mattress.

In very snowy conditions, ridges and buttresses usually provide the safest and best climbing conditions – here teams enjoy the Fiacaill Ridge

The need to travel on a suspect slope varies according to the circumstances. For example, it is seldom if ever necessary on the way up the hill in the morning, when you can vary the route or even retreat. However, it may be forced on you on the way down, in bad weather or in the dark. Travel one at a time between islands of safety and watch the person moving. Never assume that if one person crosses safely then there is no danger – this is not the case – but all use the same track. Tighten clothing, remove wrist loops and loosen rucksack straps so that it can be abandoned if necessary. If a slope has to be crossed, then traverse it high up rather than low down to reduce the amount of snow above, and thus reduce possible burial depth should it slide. It is better to be carried further but buried less deeply.

Ross Hewitt on Tough Guy, in the Eagle Ridge and Parallel Buttress Group (The Norhern Sector, Lochnagar) (photo: Sandy Simpson)

If you are caught in an avalanche

If you feel the snow slope around you move, then shout to alert others and try to delay your departure by using your axe. Attempt to roll out to the side. If you are carrying a heavy sack, get rid of it. A light sack, however, can provide some protection and will not drag you down too much – and if you are lucky enough not to be buried, you will still have your gear with you. During the avalanche, if possible get onto your back with your head uphill and try to swim or roll in order to stay on the surface. As the avalanche slows make a desperate effort to get to the surface, or thrust a limb out of the snow. Make every effort to create a breathing space in front of your face. As the snow comes to a halt it often hardens up very rapidly, so making escape even more difficult as time passes. If buried, try to remain calm so as to conserve oxygen and energy, and do not shout as the sound will not be heard on the surface.

If you see someone caught in an avalanche

Keep them in sight and note their starting position and where they were last seen. Check for further danger, and attract the attention of other people in the area. Mark the position where the victim was last seen, so as to indicate the most likely burial area. Make a thorough search of the debris for surface clues. Probe the most likely burial spots then conduct a systematic search, probing with ice axes or walking poles with the baskets removed. If there are a lot of people in the vicinity then send someone for help, but remember the initial search is vital. If a buried victim is not suffering any serious trauma injuries then he/she has about a 90 per cent chance of survival if dug out in the first 15 minutes. However, after 35 minutes this drops to only about 30 per cent. Therefore the importance of the first search cannot be stressed too strongly.

Avalanche information

There is much good written material on avalanches, and some reading on the subject should be considered as part of overall mountain safety. Avalanche reports are produced by the sportscotland Avalanche Information Service (SAIS) for much of the area covered by this guide. Much useful information and daily forecasts can be found on their website at www.sais.gov.uk. This website can also be a useful source of information for assessing climbing conditions. In addition the daily forecasts are often displayed in police stations, sports shops and hotels throughout the area. They are also posted at many popular mountain access points, such as the Cairn Gorm ski area car park and Aberarder farm.

When using the avalanche report it is worth noting the date and time of issue, as the hazard is quoted for the day of issue and reflects the existing conditions. The avalanche outlook for the following day is also given, but this is dependent on the weather forecast. If this forecast is not accurate, then the avalanche forecast itself may be inaccurate. Having an avalanche information service forecast does not absolve climbers of responsibility for making their own decisions and assessment of the avalanche hazard.

Mountain Rescue

Mountain rescue teams are made up of experienced and skilful local mountaineers who undergo regular training in mountaineering and remote-care first aid skills. Rescues are co-ordinated by the police, who should be contacted by telephone on 999 in case of an accident or possible problem.

A direct line to the Aviemore or Braemar police stations may be quicker, and the numbers are as follows.

Aviemore police 01479 810 222

Deeside police 08456 005 700

The rescue organisations will require concise information about the incident, such as the name of the climb, the location, a map reference if possible, the number injured, the nature of the injuries, how they are equipped and if anyone is with the casualty. If there are only two in the party and it is not possible to contact the mountain rescue teams or attract anyone else either by shouting, whistle or torch-light, it is a difficult decision whether to go for help or stay. This will depend on the nature of injuries, the location, weather, equipment and perhaps other considerations. If the casualty is unconscious, then this decision is even more difficult. If you do go for help, make sure that the casualty is as well equipped and as comfortable as possible, and in the most sheltered and well-marked location that you can find or create.

There is a first aid box in the corrie of Lochnagar on a small flattening midway between the loch and Central Buttress. Likewise there is one in Coire an t-Sneachda near the triangular boulder by the lochans, but the contents of these boxes are likely to vary. Both these locations are favourite gearing-up spots.