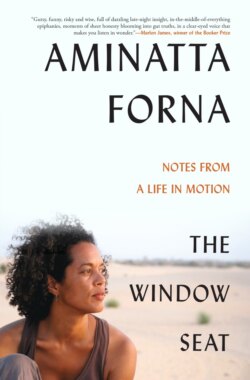

Читать книгу The Window Seat - Aminatta Forna - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSantigi

Santigi was a foundling. Or at least Santigi was as close to being a foundling as you can imagine. None of us, not even Santigi, knew his origins. He knew the name of the village where he was born but had never been back there. He did not know the names of his mother or his father. He called himself a Loko, for the reason that he understood the language, which was his only tie to his beginnings. ‘Santigi, the Loko,’ we’d call him, and he would bang himself on the chest and say, ‘Loko!’

For Yabome, my stepmother, her first memory of Santigi was when he met her off the train from school. At the time Santigi had come to live in the house with Yabome and the grandmother who raised her. At that age Yabome never thought to ask from where Santigi had come, and when her grandmother died the old lady took whatever knowledge she possessed with her. It was rumoured that Santigi’s mother had borne him alone, had left him with neighbours while she went to find work scratching for diamonds in the eastern mines and that she had died there. When she failed to return, the neighbours had given her young son to the old lady to raise. The story makes some kind of sense, but still it is hard to imagine, in a country where kinship is everything, where ties of allegiance are what binds, in a small country where everybody knows everyone else and their business, that a woman could be so alone. As for Santigi, if you asked him, all he ever told you was that he was a Loko. He made Yabome his family. When she returned from Scotland, where she went to college on a scholarship, Santigi was waiting for her. And when she married my father, Santigi came along too.

Nobody knew how old Santigi was. In her first memory of him, of being met by him off the train at Magburaka, home on holiday from Harford School for Girls in Moyamba, my stepmother would have been twelve and guessed him to be a few years older, perhaps sixteen. Yabome’s father had been a merchant who traded in gold. Possessed of unusual foresight for the time, he had made sure every one of his children went to school and to university. In those days we had several cousins living with us whose school fees my father paid. Santigi wanted to go to school too, but my father said he was already too old. Instead, he sent Santigi to adult education classes at night. Often, when I came back from school in the afternoon, Santigi would sit next to me at the dining-room table while I did my homework and copy out the questions and answers in his own exercise book.

If life had gone on in that way, maybe Santigi would somehow have realised his dream to go to college, though I don’t remember his ambitions being taken particularly seriously. His enthusiasm for learning was not, it seems, matched by aptitude. And even if it were, it would not have helped for all our lives were about to change. By 1970, Sierra Leone was a nascent dictatorship, a one-party state was on the rise. My father was arrested and jailed for his opposition to the prime minister. Our household scattered. The cooks and stewards, the driver—all departed. My cousins went back to live with their families. Mum, my sister and brother and I went into hiding and then into exile in London, where we would stay for three years.

Only Santigi stayed on, living in the empty rooms of our house. He guarded our possessions against thieves and every week he went to the Pademba Road Prison, where my father was being held. He brought my father food and clean clothes and he took away his washing, returning it ironed and folded the following week. In times like those loyalty is hard to find, and Santigi earned our family’s loyalty in return for his. But to me, looking back, what he did was more powerful than mere loyalty. Violence was on the rise, our home had been stoned by political thugs, those same thugs raided newspaper offices, threatened journalists, university professors and lawyers, and beat up anyone who dared to oppose the prime minister in his determination to become president-for-life. All our household staff had been held and detained at CID (Criminal Investigation Department) headquarters, my stepmother, too, and Santigi. Santigi had been badly beaten. As he waited at the prison gates, Santigi would have been taunted by the guards, I am sure, as were the prisoners themselves. His visits to my father were an act of loyalty and of courage; they were also an act of resistance. Like the Mothers, now the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, who come out every day in Buenos Aires to march in memory of their disappeared sons and daughters, so Santigi came every week to the prison gates to remind the authorities that my father was not forgotten. When my father was released—taken to the prison gates and let out without warning—he had no money for a taxi, but a passing driver recognised him and gave him a lift. When he arrived home Santigi was there. It was Santigi who cooked my father’s first meal as a free man.

In the year that followed, the pleasure of being reunited, of my father’s freedom, made us giddy. We danced to that year’s hit ‘Kung Fu Fighting,’ we sang and we punched and kicked the air. We, the three children and our older cousins: Morlai, Esther, Agnes and, of course, Santigi. Santigi got religion around that time and changed his name to Simon Peter and then to Santos. He carried a Bible around, and he also talked about his dream of becoming a photographer, even though he had never owned a camera. I would, in my university years, buy him a camera and I believe he did, for a while, have a small booth where he took portraits. But all that was some years off. A year after he was freed, my father was arrested again, this time on charges of treason. A year after that he was executed.

Our landlords gave us notice. Mum had trouble finding anyone who would rent her an apartment or give her a job. When she eventually succeeded in both, she didn’t earn enough money to look after all of us and Santigi too. So Santigi found work elsewhere, and he came every Sunday to wash our clothes even though Mum couldn’t pay him. He told me often that he would keep coming until the day I graduated from university. And he did.

In time, Mum remarried and Santigi was given a job as head steward in the new household. But by then he had begun to drink. He had one failed marriage and then another, each producing a daughter. He named the first Yabome and the second Memuna Aminatta after my sister and I. Santigi showed little interest in either girl. Eventually, Memuna Aminatta’s mother met a man who made her happy and she disappeared from our lives. His first wife, Marion, married again too, but remained a friend to Santigi, although it’s hard to say whether he deserved her loyalty. What it was Santigi was searching for at the time, I don’t know. He dyed his hair with boot polish, and when he sweated in the heat, the polish ran down his face. He insisted he was younger than he was, until he knocked so many years off his age that, if he were to be believed, he would be younger than my stepmother and soon almost as young as my elder brother, on whom he almost certainly had twenty years. He became a figure of fun among the children in the neighbourhood. And he kept on drinking. He remained trustworthy in every way, except one. When my parents were out, he helped himself to the contents of the liquor cabinet. He frequently turned up to work intoxicated and, after several warnings, my stepfather lost patience and Santigi was suspended.

Santigi did everything to win his job back. In Sierra Leone there exists a custom whereby a person of lower status who has offended a person of higher status will appeal to someone of equivalent or, better still, even greater status than the offended party, will plead for that person to intercede on their behalf. To ‘beg’ for them, is what we say in Krio. In the decades he had lived and worked with my family, Santigi had met dozens of people of influence and he remembered them all. Now he visited their homes, waiting patiently for an audience. He explained the circumstances of his suspension, persuaded each of his contrition and asked them to ‘beg’ my stepfather on his behalf to have the suspension lifted. My stepfather would tell the story amidst much laughter—how for weeks to come at every cocktail party, lunch or dinner he attended, every restaurant he entered, or so it seemed, somebody came up to him to discuss Santigi’s case. My stepfather, however, remained adamant, until one day he attended an international banking conference. As the delegates gathered, the governor of the state bank approached him and asked if they might have a word. My stepfather thought the governor must have something confidential to discuss. They stepped aside. In a low voice the governor said: ‘It’s about your steward, Santigi.’

Santigi was found a job as a messenger in the offices where my stepfather worked. The job gave him a decent income and a pension, and it removed him from the dangers of the liquor cabinet. Santigi still dyed his hair and now he wore dentures too; he also lied on his application form about his age, partly perhaps out of vanity, but also no doubt believing this might give him an advantage. What it meant was that he was obliged to continue working well after his retirement age.

Santigi would live to see the country all but destroyed by war and survive the invasion of Freetown by rebel forces in 1999. When I returned home in 2000, he was there to greet me. I kissed him and he seemed overcome with shyness. I wrote of him and my cousin Morlai, who was there that day to greet me too, in the memoir of my family which I published two years later, ‘I remember them both as confident lads: the flares, the sunglasses, the illicit cigarettes, the slang.’ Santigi didn’t say much during our reunion. He watched and listened awhile as Morlai and I laughed and chatted and then he picked up the pair of chickens Morlai had brought as a gift to me and slipped away to the back of the house. When I published the book, a launch was held in Freetown, at the British Council. It was a formal occasion, as book launches in Sierra Leone generally are. Santigi turned up drunk. I gave him his own signed copy. He kissed it and slapped me on the back and kept on slapping me on the back, hearty blows, even when I was trying to sign books. I saw Santigi a good few times over the years to come; he would visit when I was home. Not once was he sober. Mum didn’t want me to give Santigi money. She said he spent it on moonshine, so I gave the money to Marion for his daughter Yabome instead.

Santigi’s life began to crumble fast. He gave up his little house in Wilberforce and started moving from one rented room to another. He had retired by then and Mum could no longer contact him at the bank. She lost track of where he lived, but never entirely; if too many months went by, she always sent for news, and somebody somewhere could always tell her Santigi’s whereabouts. He came to visit less often. It’s strange how some people’s stories always end the same way. Perhaps a clue comes from my cousin Morlai, who also began to drink at the same time as Santigi—it was after my father’s execution. ‘It felt like we were going back into the darkness,’ he told me. My brother told me that years ago when he helped Santigi clear out his little house in Wilberforce, there among his possessions were dozens of pictures of my father, from snapshots to pictures torn from newspapers. A near-death experience while he was drunk shocked Morlai into sobriety. He married and had children. He grew back into himself, stronger this time. Today he’s a successful businessman, and although those things that happened to our family meant Morlai was never able to finish college, all his own children have done so. For whatever reason, even though we loved him, for Santigi redemption never came.

On my last visit home to Freetown I arrived to discover Santigi had had a stroke two weeks earlier. In the weeks that followed, Mum and I tried to get him moved to a care home, but he died before that could happen. So we bought him a coffin and all his neighbours chipped in to pay for a suit from the second-hand clothes stalls at Government Wharf. I had never seen Santigi in a suit, and I asked Mum what he looked like. She laughed softly and told me he looked good. I was back in England on the day of his funeral. I couldn’t go, so I sat at my desk and I did what writers do. I wrote this instead.