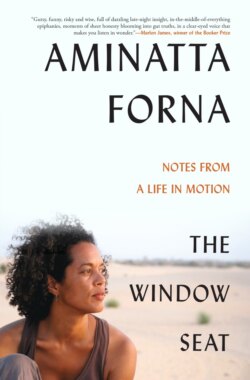

Читать книгу The Window Seat - Aminatta Forna - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Window Seat

Here are four words you rarely hear these days: I love to fly. I do. I’m talking about being a passenger on a commercial flight. Whatever emotions attend the journey, whether I am flying for work or pleasure, towards loved ones or away, once in my seat—especially if I am alone and have managed to secure myself a window seat—on seeing the marshaller signalling the plane with orange batons like a tamer before a recalcitrant circus beast, a feeling of ease comes over me. This remains true after the hundreds of flights I have taken. I love the drama of the take off. The improbability of the whole endeavour. A cat jumping is a reversal of gravity—the cat seems to pour itself upwards. An aeroplane is more like a galloping draught horse that, through sheer determination, somehow succeeds in clearing the oncoming fence. Having completed its ponderous journey to the runway, the plane turns its nose to face the long stretch of tarmac. Then comes the bellowing of the engines spooling up. The plane begins to move, slowly at first and then faster, faster. I can judge to the second the moment the nose will lift, the wheels leave the tarmac and we shudder into the air. The plane rises, dips and turns in a new quiet.

In 1967 I took my first flight, of which I remember nothing. I travelled with my mother, sister and brother. We were leaving behind Sierra Leone and my father on our way to my mother’s family in Scotland. My father was a political activist, and the mood in the country was taut. He had been arrested, detained and released, but now he was being followed wherever he went. Between them, my parents had decided my mother should leave and take us with her. It would be a year before we saw our father again. Sudden departures and arrivals punctuated my childhood. Looking back, flying and fleeing often amounted to the same thing. Though I was too young in those early days to feel the tension and sadness such departures would one day evince, I imagine I was aware, in some peripheral way, of the drama of our departure, the packing of suitcases, the ferry ride to the airport.

In quieter times we came and went on holiday from school in England, flying without the comfort of either parent. We were unaccompanied minors, which in those days carried a different quality of meaning to that which it does now. I was the owner of a Junior Jet Club member logbook in which I recorded all my flight miles with a fountain pen, which the cabin pressure would cause to leak and so I frequently arrived covered in ink. I’d hand my book to the stewardess (they were all stewardesses in those days), who would carry it forward to be signed by the captain. Sometimes, if we were lucky, the captain would invite us into the cockpit. We would walk the length of the plane in pairs, escorted by a hostess like tiny VIPs.

There in the cockpit, flying felt as effortless as sailing; the plane carried the weightlessness of a boat in water. And whereas the windows in the passenger sections were small and dull, here the sky reached out in all directions, a sensation I have only ever had in the widest of landscapes, in the Australian desert or standing before the view from the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali. In such places the sky is godlike. To fly is to be enfolded into that power. You can do nothing but fall silent. Swimming is as close as humans get to the sensation of flying as birds do. Once, scuba diving, I swam over the edge of an underwater cliff, and below me the seabed fell away some thousand or more feet. Although I was no deeper and in no danger, I felt suddenly afraid and swam back to where I could see the ocean floor.

A few months ago, I was in Heathrow’s Terminal Three, and I passed a place so familiar it put a sudden squeeze on my heart. A staircase, an empty space, the marbled floor of the terminal building, that was all there was to it. It took me a moment to realise what was missing: a cordon, maybe six or eight chairs in rows facing another chair upon which an air hostess sat. This was the place where we, the unaccompanied minors, waited to be escorted to our gates. Now the cordon and chairs are gone, the carriers who operated the international flights out of Britain, BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation) and British Caledonian (which flew out of Gatwick), ceased operations decades before, and their successor, British Airways, announced in 2016 that they would no longer accept unaccompanied minors.

To fly alone as a child was my first taste of what it might feel like to be on my own in the world. The orphaned or lost child is a trope of children’s literature: Cinderella, Anne of Green Gables, Tom Sawyer, Oliver Twist, Mowgli, Mary in The Secret Garden, Peter Pan, Harry Potter, Nemo. The young heroes and heroines are unleashed into the enormity of the world, and must prove their courage and resilience as they find home or simply a way to survive.

The unaccompanied minor was a legacy of Empire: the children of colonial officers sent from Kenya, Tanganyika, Ceylon, Hong Kong and India to be educated at boarding school in Britain. In the early days of Empire, the children would have travelled by ship and they probably would have visited their parents only once a year, if at all. Air travel changed that, allowing more frequent visits. BOAC became Britain’s national carrier and was created out of the merger of Imperial Airways and another national airline, the first British Airways. During the Second World War, BOAC was tasked with keeping Britain connected to her colonies and the airline continued to maintain those routes after independence.

I was a legacy of Empire as well. But for the Berlin Conference of 1885, which marked the end of the Scramble for Africa and at which the imperial ambitions of the European nations were formalised, my parents would never have met. Africa was stripped of her autonomy and decades of colonial rule followed. After the Second World War, Britain, penniless and under pressure from the United States, handed her colonies their independence with growing haste. Anthems were composed, flags designed, various royals dispatched to oversee the ceremonies at which the Union Jack was lowered. That was the easy part. One among many problems was that there was nobody to run these new states, all of which required lawyers, accountants, engineers, doctors. So, in the years preceding independence, young men and women from the colonised countries were granted scholarships to study in Britain. They were the Renaissance Generation, so named by the writer Wole Soyinka, a generation who came of age at the same time as their countries. One of them was my father. At a reception hosted by the British Council in Aberdeen he met a local girl who would become his wife and my mother. Through my parents, and later my mother’s remarriage to a UN diplomat, I had an unusual exposure to large parts of the world. In my family are represented the histories and nations of Britain, Sierra Leone, Jamaica, Iran, Denmark, China, New Zealand and Canada.

Universal Aunts was founded in 1921 with the primary purpose of escorting unaccompanied minors to and from airports and train stations on their way back to boarding school. I had various guardians in my time, but I certainly stayed with a Universal Aunt more than once. The company was founded by Gertrude Maclean, Aunt Gertie to the seven nephews and nieces she had living in different parts of the Empire and whom she would meet from the plane and drop at school. At first, she ran Universal Aunts out of a room next to a bootmaker in Chelsea. Restrictions on the lease meant that they could not work in the afternoons, so Gertrude and her business partner used to meet their gentlewomen clients in the powder room of the Ladies’ in a nearby department store. They still exist, Universal Aunts; their website tells the story of Gertrude Maclean. And they still care for children.

The end of Empire didn’t mean the end of children travelling alone to and from the British Isles, because the practise of sending their children home to boarding school was already well established among British expatriates. And it was a practise that rubbed off onto some of the colonised people. My father disliked everything about British colonial rule, but a British education he judged to be excellent and he was, for as long as I can remember, obsessed by the idea that all his children should have one. He had been the only child in his family to receive a Western education, in a deal allegedly struck between the paramount chief and the headmaster of the new mission school which had been built in his district and to whose strangeness people were reluctant to commit their children. The chief and the headmaster agreed that each family was to send one child to school. My father, whose mother had died when he was a child, was elected to be sent by my grandfather’s other wives. From there he won a scholarship to Bo School, the so-called Eton of the Protectorate (of Sierra Leone), and thence to Britain. He wanted the same for us. I wept and begged, but he was inflexible, and he put every cent he earned into providing it, though it meant we never owned our own home. I suppose, too, that we were safer at boarding school in England than we might have otherwise been amid the political unrest that affected so much of life in Sierra Leone, though that thought did not occur to me until my adult years.

There were consolations. To fly as an unaccompanied minor was to enter a topsy-turvy world where children were, for once, the most important people. We boarded first and had our own reserved rows, always aft, close to the galleys and the staff. We were served our meals ahead of all the other passengers, and we were given tuck boxes of games, colouring books, comics, pencils and, inevitably, a die-cast model Boeing 747 or a DC-10. The flight crew became our surrogate parents. The stewardesses were our mothers, only more patient and more elegant than our real mothers. These Stepford mothers possessed bright smiles, soothing voices and a limitless supply of snacks. They never ignored us, rather came whenever we called. The uniformed captain already looked like a hero, he commanded three hundred tons of aircraft and two hundred passengers. He did not bother much with us until after takeoff, when his smooth voice sounded over the tannoy: ‘This is your captain speaking.’ And we raised our heads to listen. For six hours we lived inside the perfect patriarchy.

Once, our plane was delayed and we nearly missed our connecting flight. Where were we? Somewhere in Europe; for some reason I think it might have been Munich. We went through a phase of flying Lufthansa, which must at that time have started flying the Freetown route. They gave good gifts but forced us to wear our travel documents in a plastic pouch around our necks. A stewardess rushed us from the plane through a back door, down passages closed to the public. At one point we descended stairs, passed through a door that led onto the tarmac and under the noses of three parked planes. A locked door meant we had to turn back. The stewardess left us while she went, I think, to get a key or someone to unlock the door. Then we were in the stewardesses’ changing room, filled with smoke and perfume, where the women went to unpin their chignons, or pin them up, to make up their faces and mend their stockings. It was like the dressing room at the Follies. A hostess came in and slipped off her shoes and jacket and then removed her blouse. As she passed the three of us, she asked another of the women what we were doing there. She had Anne Bancroft’s mouth and eyes. She stroked us on the cheek one by one, looking at us as with amused curiosity as though we were gifts left by an admirer.

Another time we became stranded in Charles de Gaulle Airport. I must have been ten or eleven. The usual systems failed, which sometimes happened when one airline was meant to hand us over to another, and we ended up waiting twenty-three hours for our flight, with no money and only the vouchers we had been given to exchange for food. We met a brother and a sister, then a girl on her own, then other unaccompanied minors, until we were a group of some eight or ten children. We raced through the airport, dodging the other travellers; in a cafe we pooled our vouchers to see what food we could buy and, at one point, we tried to persuade a man at a nearby table to give us money in exchange for some of them so we could buy toys and chocolate. When we arrived at Gatwick in the early hours of the morning, we were met by a family friend, a student nurse also from Sierra Leone. She and her boyfriend drove us home. There was nobody there to meet the girl who had been on her own and so we took her with us and slept head to toe, three girls and the student nurse, in the same bed. The next day the girl set off, assuring us she could find her way home. And so we said goodbye.

Later, when I was alone, but old enough to no longer be under the continuous protection of the airline staff, I took a flight to New Zealand to stay with my mother and her husband, my stepfather and a native of that country. The flight was delayed due to snow in London, and when the time did come for us to take off, the pilot announced that we were going to take off on half a runway, that anyone who didn’t wish to fly that day was free to disembark. I don’t know why I thought he meant a runway of half the width as opposed to half the length, but it wouldn’t have changed my decision. The plane raced to the end of the truncated runway and launched into the air, where it failed to make the requisite height and so the pilot flew out over the channel and jettisoned the fuel. Now we had only enough fuel to get us to Dublin, where the pilot said we would request permission to land and refuel. As the flight went on, it became evident that we were in the hands of a madman. At one point the pilot invited us to look out of the windows on the left-hand side of the craft from where we could see the wreckage of an airliner that had gone down some weeks or months before. I don’t remember, or perhaps I never knew which continent we were overflying, which carrier the plane had belonged to or how long the wreckage had lain there. I only recall a snowscape and the stakes that marked out the length and width of the crash site, and which made a giant cross in the snow.

We landed eventually at LAX, but by now I had missed my onward flight. We, the passengers, were bussed to a hotel where we were to spend the night. I was maybe fifteen and alone in Los Angeles. On the bus, a middle-aged British woman with dyed blonde hair worn in stiff, now-tired curls, and who was travelling with her husband, looked over at me and eventually asked if I was alone. ‘Stay close to us, love,’ she said. And so I tagged along, ending up in the hotel bar with a group of other British travellers where everyone discussed the curious behaviour of the pilot, and where the woman with the curls provoked a small row when she bought me my first gin and tonic. The next day, one of the group, a Cambridge professor of art history, took me to see an exhibition of German expressionism at the Los Angeles Museum of Modern Art, and sometime late in the evening, I caught my plane to Auckland.

In those days I believed in my own immortality, my own inviolability, as only the very young do. In all this time of taking flights alone across the world, I had never been frightened, not even faintly nervous. My fearlessness was also due to all of these events occurring in that fifth dimension of air travel. Here the normal modes of human behaviour do not apply, and we travellers are compatriots of one country. The minor resentments we accrue against other people down on Earth are suspended. There are no ordinary dangers, only extraordinary ones, like crashes and hijacking. This is why flights are, or at least were, so often the setting for movies. In an aeroplane, the passengers are joined in a shared endeavour, which in real life is as simple as arriving at their destination, and in movies may involve delivering babies or taking over the controls after the pilot and co-pilot die. It’s hard to be a bystander on a plane—you are automatically involved in whatever happens. All this disappears at the moment of touchdown, and there we are shouldering our way to the exits, all loyalty left in the overhead locker.

Remember back when people used to ‘go for a drive’ just for the pleasure of the speed and the scenery? Remember when you used to dress up to take a flight? In my family we used to plan our outfits for days in advance and then endure an eight-hour flight in what pretty much constituted a party outfit. Back then you could even smoke. Today there’s airport security, rip-off restaurants in the terminals, a lack of legroom inversely proportional to the hours of boredom, the whole process enlivened only by the thought of the drinks trolley and the dinner tray (on airlines where they still serve meals). Chicken or beef? Chicken or beef? Most passengers are so desperate that they’re practically thumping out the rhythm on the arm of their seats. And yet, to think only of the tedium is to forget the marvel that is flying.

On an overcast day the plane breaks through the cloud and into sunlight. As the plane climbs, below you clouds shift on separate strata, drifting continents, composed of shadows and light. Sunlight reflects from their dazzling peaks, improbable mountains rise, one the shape perhaps of an anvil or an oak. The occasional sight of another plane reveals the scale of the cloudscape; in it a jumbo jet is reduced to the size of a child’s toy as it seems to skate sideways across the sky, its contrail a disappearing scar. There are times when the plane flies between two strata of cloud. Sometimes a hole in the clouds above lets the sunlight through; the rays, edged in darkness, seem to radiate outwards from behind the clouds and illuminate spectacularly, not the earth but the clouds below. We call this God light.

To overfly the Sahara by day at thirty thousand feet is to feel how it might be to circumnavigate the sun. Nothing save raw light in colours from deep orange to pale yellow, very occasionally fractured by imprecise dark and jagged streaks, which one supposes to be riverbeds or rock formations. Otherwise there is but the brightness of the sand reflecting the sun’s rays and, depending on the exact altitude and tilt of the aircraft, the line where the orange glow of the ground beneath diffuses into the white band of the horizon, which in turn diffuses into blue sky.

To overfly the Sahara by night must be what space travel feels like. Gone are the indicators of life, the lights of civilisation one sees flying out over what one supposes to be the most barren of lands, even there in some crease in the earth inevitably a winking light or a lone road, leading from where to where it is impossible to know. The Sahara at night is blackness, unmarred by a single star. You cannot tell where the land and sky meet. Only there is this: beyond the reach of the wingtip, a keen-edged moon.

The last time I took a daytime flight over the Sahara was a few years ago on a return trip from Johannesburg. The moment we took off, the cabin staff toured the cabin and lowered the blinds. People found their headsets and turned on the screens in front of them. Light flared around the edges of the blinds and once, when I dared to raise mine over the Sahara, the light leapt in like a living creature. When I fly, I think of what a caveman would think if he saw this, or even knew that one day somebody would. I think of the generations in the not-so-distant past who never saw such a view. I think of those in the future who never will see that wonder which our generation’s wantonness with the world’s natural resources has made possible. The day will come when we will be nostalgic about flying. As incredible as that once seemed, the experience of having our travel curtailed by the pandemic of 2020 brought that feeling closer to many of us. One day this may be gone, sooner than we allowed ourselves to imagine.

Only in flight does one become aware of how much of the world has resisted humankind. The snow-filled corrugations of the mountain ranges of Central Europe, where it is impossible to know where one country ends and another begins. At such times, even the flight map which traces the path of the plane on the screen in front of you is as effective as pin the tail on the donkey. A ruffle of mountains falls, a new one rises. Once I imagined we must be flying over the Alps, though I think now it was the Massif Central, because a short time later, I looked down and saw the real Alps. I was entirely unprepared for their scale—they seemed to stretch upwards reaching not so much for the sky but as if to swat the plane out of it. I have skied on the Alps and I remember being awed by their beauty, but I could see only what filled the frame of my vision, which I realised, once I was flying over all 1,200 kilometres of them lying across eight countries, wasn’t very much at all.

From the window seat, landscapes can seem vast or miniature. Many years ago, my husband took a photograph of a sheer rock face illuminated by an evening light, hues of deep pink, grey and blue. Visitors to our home would stand before it and ask where the formation stood and consider how the picture might have been taken from a low-flying plane, perhaps. My husband would leave them at this for a few minutes and then tell them that the rock formation stood perhaps twenty inches high. On my last trip West out towards El Paso from Washington, DC, I passed over mountainsides the colour of the desert, which bore indentations like those a child makes in a sandpit with a shell or perhaps a fistful of knuckles. There was a dry basin the shape of an open mouth, and beyond that, at the base of a second mountain range, a settlement of houses like dots, which spoke of the mountains’ scale. I had an image of a group of settlers, having crossed one mountain range only to be faced by another, giving up and choosing to stay put.

At times like those, one is reminded of man’s tenacity, that winking light, a sharp glint where human habitation seems impossible, that lone road, the curl of smoke arising from the mangrove forest. Occasionally, I catch sight of a single vehicle travelling one of those isolated roads. I track the vehicle’s passage, wondering if the person inside can sense my gaze, trying to imagine myself in their place and they in mine. In London, where ten million people live, our house lies below the flight path for Heathrow Airport. Once, not the only time I have done this, I tried to find our street among the rows of terraces in the south-east of the city. I found the spires of Crystal Palace, then Nunhead Cemetery, where I walked the dog most days. I traced the streets: the railway line, Telegraph Hill Park. I craned my neck as we passed over, figured out which street must be ours. Minutes after we landed, I called home. ‘Would you reckon you flew over about twenty minutes ago?’ my husband asked. That seemed likely. He had been in the garden with our young son, he said, when a plane went over with British Airways written on the underside. He had looked up and said: ‘Look, that’s Mummy’s plane.’ And they had waved.

To fly over England, indeed much of northern Europe, is to see a land given over almost entirely to human use, field abuts field, the evidence of human industry. Before views like that, man appears more ant than ape. For a long time, I wondered at the circles that appeared across the American landscape, in different hues and shades from earth to green. Sometimes they appear in ones and twos within an otherwise empty landscape. Other times they arrive in their dozens, in different sizes, overlapping each other, like a Kandinsky painting. Other times still, you see them arranged in rows with architectural precision. They remind me of the crop circles that appear every year in fields in England and which many believe are the result of paranormal activity and others take to be the work of talented pranksters. The American circles are created by central pivot irrigation systems, I discovered when I eventually got around to looking it up. I regretted the sense of intellectual obligation that had propelled me towards this discovery. I liked, I realised, not knowing, gazing at them anew every time. I was interested, though, to see from photographs how the circles, so mystical from the air, were indiscernible on the ground.

Probably, if you have flown across borders very much at all, you will have flown over a war. I know I have. Consider the matter: people are killing and being killed and living in terror of being killed while, at a point precisely overhead, you are doing what? You are watching the drinks trolley edge down the aisle, handling the frustrations of plastic cutlery and those fiddly salt and pepper packets, selecting the next movie, whether it should be a thriller, a drama, a love or a war story. It’s likely commercial flights to the country have already stopped, the airport is closed or under the control of one faction or another, the borders will be tightly controlled too. Imagine a person looking up and seeing an aeroplane in the sky, the freedom the passing plane must surely represent. It must be like standing on a desert island, watching the ships pass by, without the possibility even of being able to lift a hand and wave or to shout and be heard.

When I was in my mid-twenties and still immortal, I took the controls of a light aircraft and looped the loop three times. It remains one of the best things I have ever done. My first loop was imperfect. I was so excited, I barely heard the crashing while we were upside down, which was the sound of every loose object falling from its place. I also did not compute the sudden silence as we glided onward. I had taken the plane out of zero gravity and stalled the engine. Paul, my friend, mentioned this as if in passing. I said: ‘So now we’re flying without an engine?’ The plane appeared to have lost no height; we were not spiralling earthward. He leant forward and turned the ignition. I said: ‘Can I have another go?’

We had spent the last forty minutes performing aerobatic manoeuvres. We had flown figures of eight and barrel-rolled and dived. We had looped the loop both ways, inside and out. Below me I could see the mouth of the Orwell River and the Orwell Bridge which we had driven across the day before. My only job as passenger was to enjoy the ride and to act as lookout. Look right, look left. Look up, look down. Are there any other planes? No. Spin, climb, dive, roll! It was as simple as that. After a while though, I started feeling queasy. I tried looking at the horizon, but it was never in the same place. Paul said he would take me back, but I wasn’t ready for that. So he offered me the controls because the pilot never gets airsick.

To loop the loop you must first get the plane up to a certain speed, around 140 mph, keeping the wings perfectly level. Find something to line the nose of the aircraft up to, that will help you navigate. I used the Orwell Bridge. Then you pull the joystick firmly but slowly towards your belly. The nose of the aircraft starts to rise, as the plane begins the first 180-degree turn. It feels like taking a heavy car up a too-steep hill; at any moment you might begin to slide backwards. You’re pressed into your seat by the force. Now you’re upside down and, this is the tricky bit, you need to ease off the stick so the plane floats over the arc of the loop before you begin the return journey, at which point you begin to push the joystick away. The second time I looped the loop I made the same mistake as the first. Well, it was so very hard to keep it all going upside down, to keep looking and thinking and doing. The third time, which was to be the last because Paul thought people watching from the clubhouse might start to ask why he was flying so amateurishly, I executed my loop proficiently. Every item in the cockpit, including the packet of Marlboros on the dash, stayed in its place for the entire 360-degree rotation. I flew out of the loop, my wings level, feeling like the gymnast who has just dismounted the beam having scored a perfect ten as I zoomed into the blue yonder.

As I say, in those days I was immortal. Mortality, though, was only a decade away. In my mid-thirties I went through a period of being nervous of flying. I know people who must take a sedative or be blind drunk before they fly. I had none of that. Instead, I suffered sweaty palms every time the plane lurched through a patch of turbulence. I would eye the cabin staff for evidence of an emergency, already knowing they are trained to act like automatons even as the pilot loses control and the plane goes down. Some years back my husband’s cousin flew first class to Los Angeles. What made this possible was the fact that his wife was an attendant working the same flight: they were on the start of their honeymoon. After they landed, he looked out of the window to find the plane surrounded by emergency vehicles. Sometime into the flight, someone had written a bomb threat upon a mirror in one of the bathrooms. His wife never told him. That’s how good they are.

One often hears that statistically a fear of flying is irrational. But to me the fear of flying is entirely rational, a response to the absurdity of what we are doing—flying in a pressurised metal tube, thousands of feet up, breathing recycled air. Our chances of crashing may be considerably lower than travelling in a car, but that’s not what people who are afraid of flying are thinking about; rather they’re figuring their chances of survival if the worst happens. Maybe it’s the knowledge of Icarus’s folly that makes passengers lower the blind, turn on the screen, and put on the earphones to escape into irreality.

Once, in the Gambia, in 2000, I boarded a flight I began to have serious doubts would make it. I was trying to get to my family in Freetown at a time when commercial airlines had stopped flying there, as they did during the civil war and would again fourteen years later as Ebola gripped the country. I wrote about my return to Sierra Leone and that flight at the time:

From the outside the West Coast Airlines aircraft looked respectable enough; inside it was another matter entirely. The seats were tattered and stained, many of the seatbelts were broken, the overhead lockers were wooden and refused to open; instead our hand baggage was taken from us and thrown into a void in the tail of the aircraft.

As we waited in our seats before take-off I watched the two Russian pilots making their way to the cockpit. I wondered, briefly, what in the world could have brought these two men to be here, commandeering an ageing aircraft in and out of unstable African states.

What I didn’t include, because it happened three years later, was that the same aircraft, on its way from Freetown to Beirut, went down with the loss of one hundred and forty souls. I was in Freetown at the time, the war had been over by a year, it was the day after Christmas. Everywhere I went there was someone who knew someone on that flight. We were all just one degree of separation from tragedy.

Somehow that experience brought me, rather than a heightened sense of panic, a renewed calm about flying. I stopped worrying about what I could not control. Now it becomes a moment to make peace with the possibility of death. I think about the things that I have done and those I have left undone. (I always feel just a tad more relaxed when a book I have been writing is finished.) I think about those people I love and have loved. I consider the movie programming and discard it. I fold my hands in my lap, lean back and turn my head to the window and wait for the force that pushes me back into my seat.