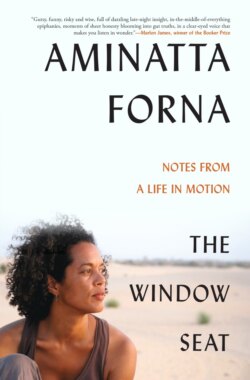

Читать книгу The Window Seat - Aminatta Forna - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIce

When I go to the theatre, I like to sit a good way back from the stage. There is no mystery to this. I’m afraid the moment might come when an actor steps down from the stage and chooses me, me—out of all the upturned faces of the members of the audiences—to go on stage. This last happened on my first date with the man who is now my husband. The theatre was tiny, probably seating no more than thirty. The distance from our seats to the stage was perilously short. A performer who looked and danced like a budget Leo Sayer pulled me from my seat and made me dance on stage. I’m the kind of person this happens to a lot. Perhaps because in many of the places I have lived I tend to stand out. Also, I do not have resting bitch face. Instead I have the sort of face that makes people think I am kindlier than I am. So, like the career criminal who never sits with his back to the door, I avoid the seats near the stage. Nobody enjoys the humiliation of a forced public performance, but my fear runs deeper than that and the psychological trajectory, for once, is a straight line.

In 1970, newly arrived in London, my stepmother thought it would be a fine idea to take us all to a show, my sister, brother and I. The production was Disney on Ice at Wembley Stadium. The arena sits twelve and a half thousand people. Our finances at that time were a little thin, so this was a special Christmastime treat. We were seated in the front row which afforded an excellent view of the ice. We had chocolates and fizzy drinks, all of which added to our state of excitement. Our seats were at the end of the row—my stepmother took the place closest to the aisle, I sat next to her, because at six I was the youngest, then came my sister and finally my brother, the eldest. For the ice spectacle the entire floor of the arena was converted into a magnificent rink. Being, at that time, a child of Africa, I had never seen real skaters; probably I was only peripherally aware that such an activity existed from reading the kinds of Victorian children’s stories available at the British Council Library in Freetown. In no way could my imagination have prepared me for such a sight—all the characters from my favourite films right there in front of me, gliding forwards and backwards, they spun, pirouetted and leaped, moved by some invisible propulsion. There was music of course, and probably some attempt at a narrative; I don’t remember anything about that. This is what I do remember: Snow White leading the Seven Dwarves in a conga line; Dumbo, flat on his belly, legs to the four directions of the wind, rotating slowly centre ice. How we laughed! And then, to the sound of the ‘Bare Necessities,’ led by Mowgli himself, joined by Bagheera, Shere Khan, King Louie, Colonel Hathi and Baloo. Gentle, dumb but not so dumb Baloo, my favourite. Baloo patted his stomach and dipped his head in that ‘Aw shucks’ way he had. He stumbled, pretended to trip and righted himself as Mowgli chased him around the ice. Baloo was the star of my show.

Suddenly the performers split up and began skating in multiple directions. They were coming off the ice! And they no longer glided but walked with an odd, clunky gait, hobbled by their skates. They were taking children from their seats, one by one, lifting them up and carrying them off. And then there was Baloo. He reached past my stepmother and snatched me from my seat. Baloo up close was not the Baloo of the Jungle Book film or even Baloo of the ice. This Baloo had a face made of plastic, and hard plastic paws. And his eyes were not soft, brown, bear eyes. Through the cut-out holes of the mask, I could see the small, blue eyes of a man. I cried out. I wriggled. And I fought. But Baloo was strong, Baloo held on tight. And then we were on the ice, speeding away from everything I knew. The audience clapped and cheered. ‘Take me back,’ I cried. And Baloo, my once beautiful Baloo, dug his fingers and thumbs hard into my body, leaned forward and hissed with hot breath into my ear: ‘Shut up, you little shit!’