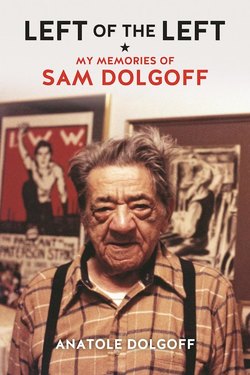

Читать книгу Left of the Left - Anatole Dolgoff - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

9: The Clap Doctor from Chi

ОглавлениеSam was fortunate to form close friendships with a number of colorful characters in his Chicago days. Some served as mentors; others he simply palled around with. He hit it off especially well with a tall, rugged-looking fellow of bad complexion, dirty knuckles, and greasy shoulder-length hair by the name of Dr. Ben Reitman—celebrated in Wobbly circles as “the clap doctor from Chi.” They often met at the forums conducted by “hobo college,” a fraternal organization that provided food, lodging, and education to the down-and-out on skid-row—West Madison Street—and less often at more dignified forums run by the anarchist Free Society group. The two men had more in common than poor personal hygiene. Each was the product of poverty-stricken Jewish immigrants. Each went on the bum early; Reitman was riding boxcars at age ten. Though Reitman was able to get training, and became a doctor, each man was restless, rebellious, difficult, and tenderhearted.

Reitman has been excoriated by feminist historians as a perfect son of a bitch, a cad, for what they deem his shabby treatment of Emma Goldman in the course of their torrid love affair of 1908 thru 1917. Not that Sam disagreed. Emma summed up Reitman’s faults succinctly: his vulgarity, “his bombast, his braggadocio, his promiscuity, which lacked the least sense of selection.” Sam once told his close friend, the historian Paul Avrich, that “it was impossible to have too low an opinion of him.”

On the other hand, he liked the guy. Reitman earned his “clap doctor” appellation because he treated street prostitutes for VD at a time when no “respectable” doctor would touch them. This, long before penicillin was discovered. His “practice,” consisted of whores, skid-row bums, thieves, destitute immigrants, and low-lives difficult to categorize. These were the people he grew up with and with whom he lived. He was a pioneer of public health, setting up free clinics for the most wretched of the poor, and with Goldman he toured the country advocating birth control, women’s rights, and other disreputable causes. Hard to hate a man locked up at night for dispensing birth control advice in public, but let out during the day to treat imprisoned prostitutes and work in the hospital laboratory. And, not least in those Prohibition days, you could count on him for a prescription to buy legal booze.

Certainly, Sam thought, his good deeds deserved some positive mention from Emma’s bitter defenders. But my father was in many ways an old-fashioned man. “Is the poor woman entitled to no privacy, no peace?” he pleaded when Emma’s intimate love letters to Reitman were published in the 1980s. To which the answer is “no.” She belongs to history now, and history loves scandal, revelation.

Reitman was kidnapped in San Diego while on a speaking tour with Emma in 1912. They had come to lend support to the Wobblies caught up in a free speech fight so vicious it drew national attention. While Emma was detained forcibly by authorities in another part of town, eight bastards pushed their way into his hotel room, drove him into the desert night, stripped him naked, beat him, burned IWW into his buttocks with a glowing cigar, poured hot tar over him head first, and rolled him. Then they wrenched his balls and shoved a club up his anal cavity. He nearly died.

That was all long before Sam knew Ben. So was Ben’s affair with Emma, whom he last saw in 1919, the year she was deported. It was an intense episode in a full life. He placed flowers on her grave the day of her burial next to the Haymarket martyrs in Waldheim Cemetery. Ben died three years later, in 1943. Sam missed him, would always speak of him with affection. “Reitman never turned down anyone seeking help,” he said.

It was rumored he left $1,500 in his will—a small fortune—for the bums on West Madison Street to drink to his memory. Sam had no doubt this was true.