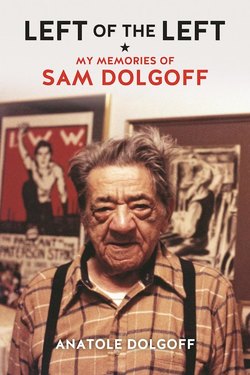

Читать книгу Left of the Left - Anatole Dolgoff - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3: Sam’s Personality – Early Life – Other Things

ОглавлениеSensitivity to the world’s great anguish and its wrongs were at the core of my father’s character; he had an organic identification with the abused and exploited of this world. I remember sitting on the living room couch with him one evening in the last months of his life, following Mother’s death. The year was 1990 and the TV news was filled with the economic collapse of the Soviet Union. The camera lingered on the care-worn face of an impoverished old woman, draped in black, symbolic of the desperate plight of the Russian people. My eighty-eight-year-old father sobbed.

“Who is to feed her?” he asked.

Sympathy for those who suffer is, fortunately, a thoroughly human trait. What made my father become an anarchist was his hatred of those institutions that perpetuated and profited from the suffering of others, namely the State, the Capitalist system, and organized, entrenched religion. In his reading of the world they were the embodiment of arbitrary authority and his hatred of arbitrary, hierarchal authority had no bottom. Nor was there a bottom to his contempt for those who held power within these institutions. He took it all personally.

His scorn could reach operatic proportions.

There was the time he flung a chair across the living room at the grainy TV image of Secretary of State Dean Rusk calmly explaining in his composed manner the necessity of the Vietnam War. “Go ahead, that will do a lot of good,” Mother taunted him. My father despised diplomats.

Then there was the quiet Sunday afternoon he rose from his chair upon reading Kipling and threw his complete works, book after book, out our fifth-floor window. It was an action he later regretted, because he actually admired Kipling’s work, but the man’s war-lust and racism infuriated him.

His comments concerning the “greats” of this world came marinated in lye; he was most defiantly not a subscriber to the Great Man Theory of History.

Of Stalin, the Man of Steel: “That evil sonofabitch is lower than whale shit!” And the sonofabitch had a special twist to it.

Nothing pleased him more than deflating an inflated reputation. He mocked Lenin (“that Mongolian conniver”) and Trotsky (“you mean Brownstein, the tailor?”) as much for the cultish worship they inspired in their followers as for their betrayal of the Russian Revolution. He relished the tidbit that came down from Emma Goldman, who was a close friend of Lenin’s wife during the early years of Bolshevik rule (“Seems the Hero of the Revolution was less than a hero of the bedroom”).

The Founding Fathers fared no better. The thought of them curled his lip. “A bunch of slave owners, autocrats, smugglers. Tom Paine was the only one any damn good—and they got rid of him. Read the Constitution they came up with. See if you like it.”

As an adult I enjoyed playing the foil to his hyperbole; I might say, “President Johnson wants to leave his mark on history.”

To which the answer might come, after a caustic pause: “You mean, he wants to drop his turd on the sands of time!” He was fond of Shelley’s “Ozymandias.”

Mother said many times my father wore his crusty shell as protection against the pain of the world; the vituperation he used often was not for comic effect. He was in fact the gentlest of men. He never referred to Mother as his “wife”; he felt the term demeaned her. Rather she was his “life companion” and he meant it—although he was not above calling her “my ball and chain” in front of visitors for the naughty pleasure of watching them squirm. He preferred that Abe and I call him by his first name; he did not like the authoritarian implications of “father.” Nor did he demand that we respect him because we lived under his roof. “Respect me if you feel I’ve earned it,” he often said to us. You could argue with Sam, tell him to shut up as we did regularly, and he would do so, meekly. He was delighted when my six-year-old daughter Stephanie talked back to him. “I like a fresh kid! A rebellious child!” he’d say, and hand her a quarter.

Then, for no apparent reason, the broken baritone would burst through the crusty shell. He would start to sing: at home, on the street, wherever the spirit moved him, in and out of tune at the same time. He loved the great IWW songs printed in its Little Red Song Book. “Hallelujah I’m a Bum,” was a favorite, though there were any number of others.

Be cheerful and gay, for the spring time has come.

You can throw down your shovels and go on the bum

Hallelujah, I’m a bum

Hallelujah, bum again,

Hallelujah, give us a handout

to revive us again!

Beyond the obvious mockery and irreverence, Sam saw pathos in the lyric.

I suppose you could trace Sam’s rebellious personality in part to Grandfather Max and to his roots in a shtetl (that is, a tiny secure Jewish community) near Vitebsk, a city just inside the eastern border of Belarus. “Do not go back. Nothing is left,” a friend from that part of the world advised me recently. “The Lithuanian Fascists wiped out everything and everybody in 1941: thirty-five-thousand Jews in mass graves, at least. Anyone tells you he can trace your family is just taking your money.” But in the late 1890s Vitebsk was home to a vibrant Jewish culture that spawned Marc Chagall and so many others.

Grandpa Max was a contrarian from the start. He scandalized the shtetl by smoking cigarettes on the Sabbath and enraged my great grandfather, a rabbi, by renouncing religion altogether. He was an atheist during his waking hours. When he slept, though, between snores you could hear him recite the ancient Hebrew prayers in a clear voice.

Around 1900, Grandpa Max worked as a commissary clerk on the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

They had a bunch of railroad cars where the track and train men slept and another car where Grandpa Max supplied them with cigarettes, tobacco, underwear, and different things. He also had charge of their feeding, and pinch hit as their timekeeper. So he got to know how exploited the men were and he bonded with them. When they struck for better pay and conditions, his supervisor, in the spirit of the times, called for the Cossacks, who clubbed them from horseback. “How can you do that?” Max asked. “These men slave for you every day. You know they are desperate.”

“You are management,” his boss said, “You have a good job for a Jew. You must decide whose side you’re on. That’s the way it is.”

“Nobody owns me,” Max told him and he was fired. At about the same time the Tsar wanted him as cannon fodder for the upcoming Russo-Japanese War. So Max skipped to America, where he learned to be a house painter, and sent for grandmother Anna and three-year-old Sam in 1905. Along the way he simplified the family name from Dolgopolski to Dolgoff.

Max was basically a kindly man, who accepted the world as it is and not as it should be. The true revolutionist of the family was Max’s brother, Tsudik, who remained behind. I’ll let Sam tell his story:

Through the many years spanning the 1905 Russian Revolution to my father’s death in 1945, we had no news about what happened to Tsudik and doubted strongly that he was still living. But (much later)… I was given a copy of the Russian Communist Jewish periodical Soviet Homeland which, to my great surprise, (contained) a photo and an obituary article about my uncle. It read, in part: “Tsudik Dolgopolski was born in the village of Haradok, not far from the Vitebsk. At 13 years of age he began work in a brush factory. In 1909 after many difficulties he became an elementary school teacher. In 1926, his novel Open Doors was published in which the great events of the October Revolution were graphically described. In 1928 his book On Soviet Land was published. Later, two volumes of memoirs, Beginnings and This Was Long Ago, appeared. Dolgopolski’s writing graphically described the awakening of Jewish life thanks to the achievements of the October Revolution.”

Sam continues, “This sketch omits the fact that Tsudik was sent to Siberia for fomenting strikes and demonstrations against the Tsar, that extracts from his Sketches of Village Life were printed in the New York Jewish Daily Forward, and that my uncle declined the Forward’s invitation to come to New York as a staff writer. More importantly, a full report from a reliable source revealed that my uncle (was) condemned to hard labor in Stalin’s concentration camps where he died.” I have since learned that Sam’s belief about his uncle’s demise was incorrect. It seems that Tsudik managed to survive both Stalin’s camps and the subsequent Nazi invasion. He died in 1959.

Imprisoned by two tyrants, Uncle Tsudik was a man for many a season. The only family anecdote about Tsudik that comes down to me through the years was from Sam’s brother, Louie. Seems Tsudik knew Stalin’s NKVD were coming for him, late at night, as was their way. So he left the door open and waited for them to thump up the stairs in their winter boots. “Pigs, can’t you see she has just polished the floor! Respect my wife,” he snapped at them as they burst in. And so they stood at the door, abashed, as Tsudik rose from his chair. The tale may well be apocryphal, but it moves me to this day.

There is another story that may well be apocryphal that also moves me. It arrives from that far away place in the mind where what you think was told to you merges with what you would like to imagine was told to you. Yet the image is indelible. I “see”—or do I feel?—my future father, the four- or five-year-old Shmuel, in the knickers children wore in those days. There is the carcass of a dead horse abandoned in a vacant garbage strewn lot, a feast for the flies and rats. And, in a metaphor of his life to be, my father-to-be is astride it, crying, imploring it back to life, while several adults, Grandpa Max among them, are yanking him off the fetid thing.

The diaspora of Eastern European Jews to New York’s Lower East Side has acquired a polyurethane coating of nostalgia as it recedes ever further in time. The upper-middle-class descendants of this Diaspora are taken on tours of a meticulously preserved nineteenth-century tenement and to colorful relics of the old days: Gus’s Pickles, Yana Shimmel’s Kinnishery, Katz Deli, and so on. Fiddler on the Roof makes for a good cry at a safe distance and allows for more than a bit of smug self-satisfaction. Not many people have read Michael Gold’s Jews Without Money, which presents a bitter, astringent picture of immigrant life—in other words, the way things were.

This is what Sam had to say as an old man, looking back:

Upon our arrival in New York we lived in a typical Lower East Side slum on Rutgers Slip, a block or two from the East River Docks, in overcrowded quarters. The two toilet seats for the six families on each floor were located in the common hallway. There was no bathroom. A large washtub in the kitchen also served as a bathtub. When another immigrant in need of shelter came, a metal cover over the washtub also served as a bed. There was no central heating, no hot water, and no electricity. Gas for illumination and for hot water in summer was supplied only by depositing a quarter in the meter. Neither the electric trolley nor the auto were in general use and both commercial and passenger traffic was horse drawn.

Nevertheless there was richness to life; the seeds of his anarchist philosophy were planted in the hard dirt of poverty.

Despite the horrible economic conditions, there was, at least in our neighborhood, far less crime than now. We could walk the streets at all hours of the night unmolested, sleep outside on hot summer nights and leave our quarters unlocked and feel perfectly safe. To a great extent this can be accounted for by the character of the new immigrants. The new immigrants, fortunately, had not yet become fully integrated into the American “melting pot.” The very local neighborhood communities, which enabled the immigrants to survive under oppressive conditions in their native homes, sustained them in the deplorable new environment.

The new arrivals lived in the same neighborhoods as did their friends and countrymen, who shared their cramped lodgings and meager food supplies, found employment for them where they learned a new trade. They helped the new arrivals in every possible way, at great sacrifice, to adjust to the unfamiliar conditions in their new homes. Thus, upon arrival, as already noted, my father was taught the painting trade by his fellow countrymen, who lodged and sustained him until he could establish himself.

My father became a member of the Vitebsker Benevolent Society, which provided sickness and death benefits, small loans, and other essential services at cost. Fraternal and other local associations actually constituted a vast integrated family. Neighbors in need received the widest possible assistance and encouragement, and the associations promoted the fullest educational and cultural development.

Social scientists, state “welfarists” and state socialists, busily engaged in mapping out newer and greater areas for state control, should take note of the fact that long before social security, unemployment insurance, and other social service laws were enacted by the State, the immigrants helped themselves by helping each other. They created a vast network of cooperative fraternities and associations of all kinds to meet expanding needs—summer camps for children and adults, educational projects, cultural and health centers, care for the aged, etc. I am still impressed by the insight of the great anarchist thinker Proudhon who in the following words outlined a cardinal principle of anarchism: “Through the complexity of interests and the progress of ideas, society is forced to abjure the state…. Beneath the apparatus of government, under the shadow of political institutions, society was closely producing its organization, making for itself a new order which expressed its vitality and autonomy. (General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century [London: Freedom Press, 1923], 80.)

When Grandpa Max pieced together the money to move his family to the less crowded “wilds of the south Bronx,” their meager possessions were loaded onto a horse-drawn cart. Grandma Anna wept and embraced the other wives as if she were crossing the Atlantic again. It might as well have been. The trip took nine hours through congested streets and the virtually impassable Willis Avenue Draw Bridge. Can you imagine the pile up of loaded down carts, teamsters, horses, horseshit, flies, and stink?

Sam loved the common horses that did the world’s hard work. He would approach them on the street and pat their sweating hides. Though it is hard to imagine a more unsuitable soldier than my father, he was, along with cousin Izzy, enlisted in the U.S. Cavalry and sent to hot, faraway, hostile New Mexico: two underage Yiddish kids circa 1916. They served as grooms, mucking out stables and swabbing and feeding the animals. Sam liked that part of it, and—contrary to what you might expect—he liked his sergeant, too, who counseled him in a kindly way on how best to adjust to the disciplines of Army life. That did not prevent Izzy and Sam from deserting at the first opportunity.

It is clear to me Sam was a restless, sensitive boy condemned to hard labor and poverty, searching to know the world, searching for a way out. School certainly did not provide that way out. It was instead his introduction to hierarchal authority, and a profoundly unhappy one. He often described grade school as a hell hole of neo-Victorian child abuse.

You’d walk through the halls and hear the bedlam coming from the rooms. “Ouch! Leave me alone you bastard.” Whoop! You could hear the rod come down. Children would run out the rooms screaming and their teachers—who were like prison guards—would drag them back in by the ear. You sat on benches and recited things by rote. The teacher would walk behind you with the rod. You had to look straight ahead. You never knew when the rod would come down on you or if you had to open your hands for it in front of the room. The object was to break the child’s spirit, make an obedient citizen.

Eight-year-old Sam faced the added obstacle of having to help his father support a family of five children. That is when he took to delivering milk and bread from a horse-drawn wagon, seven days a week: school days, six to eight each morning and four to six in the afternoon; Saturdays and Sundays all day. It paid three dollars a week. Under those circumstances, he found it difficult to pay attention in class and, worse yet, he was plagued with poor eyesight. And he was rebellious. So he was left back, and surrounded by younger boys in class. They ridiculed him because he could not see well, called him “dummy,” and did to him all the nasty things oppressed children can do.

He graduated elementary school, then found work ten to twelve hours a day on the factory floor of the Continental Can Company. But he was rebellious. Finally, Grandpa Max felt it best to leave his obstreperous son with his friend, who was a small-time contractor: “Stay on top of him, because he don’t like to listen.” He did learn to be a painter, but he also learned that his salvation lay in escape: San Francisco, Shanghai, the U.S. Cavalry, the Open Road, and ultimately, himself.

Sam’s “formal education” ended at the eighth grade, but not his education. These are among my strongest boyhood memories of him: He would arrive home from work with the smell of sweat and turpentine about him, paint encrusting his nails and glasses: exhausted, haggard. After eating, he soaked in the bathtub for an hour; he had a tight, muscled body in those days, not the bloated, emphysema-distorted one that many who knew him in later life remember. Then his education began. He would lie in his bed surrounded by books and obscure radical publications piled as high as the mattress. And he would read. Not just political theory. Everything. Night after night, every weekend, each spare moment, he would lie on his back in a haze of cigarette smoke, reading.

He took his learning seriously but not his learned self. Years beyond these childhood memories, in 1971, Angus Cameron, the distinguished editor at Alfred Knopf, prepared to publish Sam’s ground breaking Bakunin on Anarchy. It was—is—a scholarly treatise on the towering nineteenth-century Russian revolutionist. Sam had translated Bakunin’s writings from various languages into English; the manuscript was replete with footnotes and references, which in some respects are the most important part of the book.

“Your credentials?” Cameron asked.

“Doctor of Shmearology, New York University, with a concentration in shit houses and boiler rooms,” Sam answered with mock pomposity, describing what he had painted there. It was the closest he had ever come to a college degree.

Cameron, a man of humor, appreciated the answer. “Bet you never expected to be in this office,” he exclaimed.

“As a matter of fact, I am well acquainted with your office!” Cameron was astonished to learn that by astounding coincidence Sam had painted his office several years earlier.

In fact, Sam’s knowledge of history, social movements, philosophy, psychology, and literature was vast and deep on many fronts. It started when he was a young man, taken under the wing of many leading anarchist and socialist intellectuals of the time. “They were my university,” he said.

He would take no job that required him to hire or fire another worker; he considered it immoral to exercise the power of bread over a fellow human being. Nor would he follow the career path of many an ex-radical and take the cushy jobs in the union bureaucracy he was offered. He wanted no part of union corruption and the betrayal of its members.

“Sam! Sam, it’s great to have you back!” It is Martin Rarback, the all-powerful Secretary Treasurer of the all-powerful District Council 9 of the Painter’s Union. Council 9 had all the large-scale work in Manhattan and the Bronx—basically NYC—tied up. Every office building, apartment project, public space, old and new, had to go through Council 9.

Sam had left the union years earlier when it was under communist domination, preferring to work for peanuts on his own. But now it was the 1950s and he wanted back in. So there he is in the large office of Rarback, who is facing him behind his large desk. He is genuinely delighted to see my father. They remember each other from the old days when Rarback was a burly young rebel who served as Leon Trotsky’s bodyguard during his brief stay in NY—before Trotsky headed to Mexico, where Stalin’s ice-pick awaited him. He eyes my father with a combination of warmth and veiled contempt. But the nostalgia wins out.

“Still at it, eh Sam? The Wobblies, the old days! I know what you think, seeing me here ‘taking Pie.’ Big office, good money, soft.” He grows passionate now, leans forward. “But Sam, let me tell you, I’m the same man. When those barricades go up, you’ll see me there!”

In the course of waiting for those barricades to go up, Martin Rarback came under criminal indictment for being neck deep in corruption. The inexcusable part to Sam was that Trotsky’s former bodyguard, who now lived at a lofty twin towers Central Park West address, took kickbacks for having his men work under substandard, dangerous conditions. He considered him a depraved person.

This is as good a time as any to mention that Sam had guts—a quality of his that I discovered in a strange way when I burst home from school one ordinary day to find him in bed, in fetal position, wrapped in blankets, shivering violently, and Mother draped over him, cradling him in her arms. Sun streamed in through their bedroom windows. It was broad daylight. Sam was never home at this time and never in bed. I was eleven years old.

He had been brought home by two of the men on the job. Seems he had cleaned his arms and neck with a rag soaked in benzene; that is how you removed the oil-based paint. But he had neglected to dry himself thoroughly and lit a cigarette, which ignited his right arm in flames. It was a revolting scene and as his flesh started to roast, some of the men started to gag and vomit from the odor. And in those seconds when he could have burned to death he extended his flaming arm outward—horizontal to the ground—and walked calmly to the other end of the large room, some thirty feet, and thrust it into a pile of sand. The men said they had never seen anything like it.

Sam went into shock; he could not stop shivering. Then he caught the flu and it took him ten days to get back to work. Not once did he mention the incident to us.

Old-fashioned guts: intestinal fortitude. The second time I was surprised to find him home in the afternoon involved high scaffold work—which he was wary of, and took only when there was nothing else to feed us. Far above the pavement, some ten stories up, he discovered the hard way that his partner, a new man, did not know how to tie the security knots. The scaffold turned into a lever, which rotated in a vicious arc, and threw the man off. Desperately, he hung on to the scaffold, torso and feet dangling, rigid with fear. As happens in New York, a crowd materialized in an instant to stare upward at the unfolding horror. Sam was at the pivot point twenty feet or so above the new man. He, too, had been knocked off balance and clung to the vertical cable. Somehow, he got to the new man, spoke to him gently, and holding him firmly, guiding him, managed to slide the two of them down the cable to the ground. The audience clapped, which was nice, then dispersed.

I remember his hands that day. The cables had sheared off a lifetime of calluses, and left them red, smooth, and painful. But the interesting thing to me now, as I write this, was his response: he got on the scaffold the next morning. And he took the new man, a Dominican immigrant, up with him after a stern talking to, and taught him the ropes. The man explained he was desperate for the work and had lied about his experience, thinking he could pick up what to do by watching Sam. All Sam had to hear was that the man was desperate for the work.

I think it is self-evident that Sam’s life strategy was not designed for economic advancement. You can add to that his refusal to take unemployment insurance for many years because he thought it charity from an institution he opposed: the State. Nor would he accept a tip or bonus, which he thought demeaned him. He put food on the table with back-breaking labor. Mostly he painted the decrepit apartments of the crumbling nineteenth-century tenements in our neighborhood. He was a superb old-fashioned craftsman: able, in the age before hi-tech, to match colors perfectly; even those that have faded from exposure over the years. He knew how to plaster, spackle, provide primer coating, and otherwise prepare a wall before actually applying the finishing paint that you see. It was incredible the way he could cover one-quarter of a wall with a single dip of the brush and long seemingly effortless strokes of his right arm—all to the rhythm of a Wobbly tune that he exhaled faintly, as unconscious to him as the Hebrew prayers were to his sleeping father.

I have often asked myself why a man able to destroy a trained trial lawyer in public debate was no match for a slumlord who wanted him on the cheap. Sam was incapable of bargaining effectively on his own behalf. They sensed his need. He always gave in, consistently underestimating the time element, especially in the winter months when pickings were lean. “Boys, go help your father,” Mother would say to us as he toiled late into the night. Abe and I would find him on the top floor of a forsaken tenement somewhere, a naked light bulb revealing him in coveralls on a rickety ladder, long shadows dancing across the walls. The wide open windows and the piercing cold did not hide the oily paint smell, which triggered my gag reflex, nor did it prevent choking from the fucking dust everywhere. I hated being in the room. But I can still sense my father’s simple pleasure at having his two boys, his sons, by his side in the night.

This lasted about three minutes. He did not want us anywhere near what he had to do. “Go home, boys,” he’d say. “Tell your mother, ‘Soon, not to worry.’”

“Soon” stretched to the incipient morning light.

In 1948, Sam painted the home of a Mrs. Harris, which required an interminable subway and bus journey “to the country”—that is, to far away Jamaica, Queens. I was dumbfounded that she and her family occupied an entire house, and that grass and trees grew in front and in back of the house! Every Saturday morning, for months after the agreed-upon work was completed, there came the dreaded Harris phone call in a whining, wheedling accent that grated like chalk on a blackboard:

“Sammy, pleees, one more thing…”

The woman was insatiable—a tapeworm of demands. Like shit on my poor father’s shoe, there was no shaking her off! Mother loathed her. Still, Mrs. Harris kept calling to extract every ounce of advantage from my father’s hide. She smelled his essential decency, his good heart, his inability to say “no.”

The Harris Job passed into family lore. Abe shared Sam’s mordant wit and it became a running joke, a bond of affection between them.

“Finish the Harris Job yet, Sam?” he’d ask whenever he came to town. (He lived first in Houston, Texas and then Chicago.)

“Just a few things, here and there,” Sam would answer, deadpan.

The joke went on like that forty years. Abe asked Sam about the Harris Job for the last time in the final weekend of Sam’s life, beside his hospital bed. Sam smiled “Just a bit here and there,” he answered, deadpan.

That is how he was. He and Abe spent their final Sunday afternoon together singing the old Wobbly songs. They are piercingly beautiful sung in the right spirit. I came the next morning to take him home by ambulance in a stretcher with oxygen tank. He was not supposed to die just then. Dr Inkles predicted he had a month or two. Sam knew better. “It’s getting dark. Turn on the lights,” he said as I eased him into bed.

“It is broad daylight,” I snapped.

“Give me the phone! I want to call Federico!”

Federico Arcos was an old and unrepentant anarchist, an autoworker in Windsor, Ontario. As a boy he had fought on the barricades of Barcelona with a rifle from the Crimean War that was taller than he was. My father loved Federico. I handed him the black rotary phone with the long cord. He insisted on dialing the number himself. I do not know where he got the breath to speak without panting.

“Hello Federico! Listen, I’m going to go soon. I wish you farewell. Keep up the fight, good comrade. Salud!” And he hung up.

He died that night.